Monkeys take to the lanes as the sun shines on the streets in India. From the modest dwellings of small slums to the esteemed precincts of the parliament, these creatures roam freely, showing a notable lack of discrimination. Everywhere you look, whether in Old Delhi or Lutyens Delhi, there are monkeys. This notorious animal has always been known for sharing habitats with humans and engaging in activities such as stealing and vandalizing. They are mostly seen strolling, playing, fighting, lounging with each other, jumping on the rooftops, and dangling in midair on those twisted electric lines. Monkeys, as among the earliest inhabitants of the city, have seen the landscape evolve with time. However, the audacity of their actions has taken a more extreme turn, leading to a surge in monkey attacks within the capital. This alarming trend has birthed an unexpected profession of Monkey Whisperers.

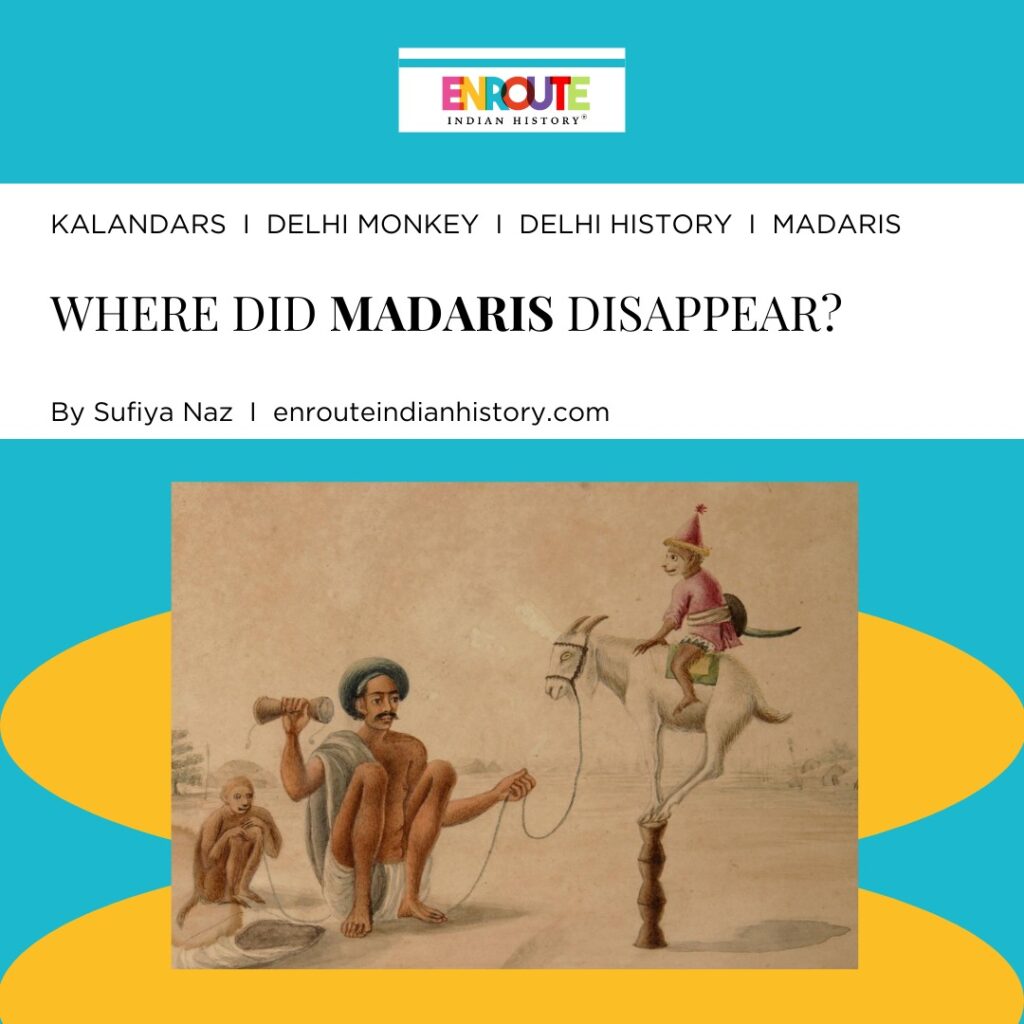

Once allies turned adversaries, this narrative unveils the transformation of erstwhile monkey whisperers known as ‘Madaris’ or Kalandars. These individuals, once enchanting the streets with their enthralling performances alongside their animal companions, are now at odds with these mischievous creatures. These monkey whisperers, once integral to daily amusement, were trendy on streets, enigmatic figures in children’s tales, and even featured prominently in Hindi cinematic narratives.

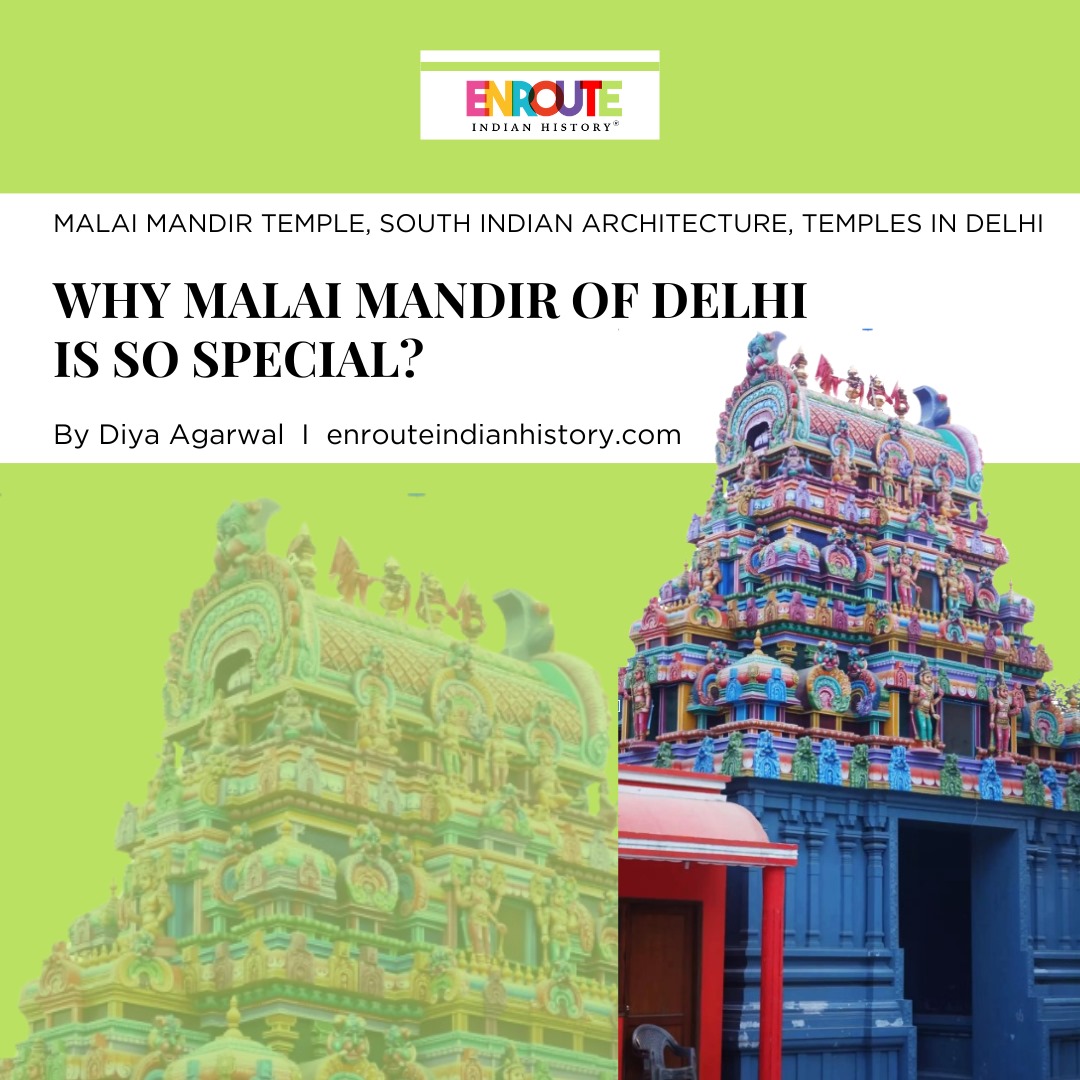

History of Madaris and Kalandars

In the rich tapestry of Indian myths and legends, monkeys are believed to be descendants of the revered Hindu deity Hanuman. In the city of Delhi, much like other regions in India, Hanuman Temples are inhabited by these monkeys. Upholding age-old traditions, people in Delhi hold these monkeys in high regard, offering them sustenance, especially on the auspicious days of Tuesday and Saturday. It is believed that feeding monkeys not only absolves one of sins but also accrues positive merits. This practice, deeply rooted in historical significance, underscores the enduring presence and reverence for monkeys in the cultural landscape of Delhi.

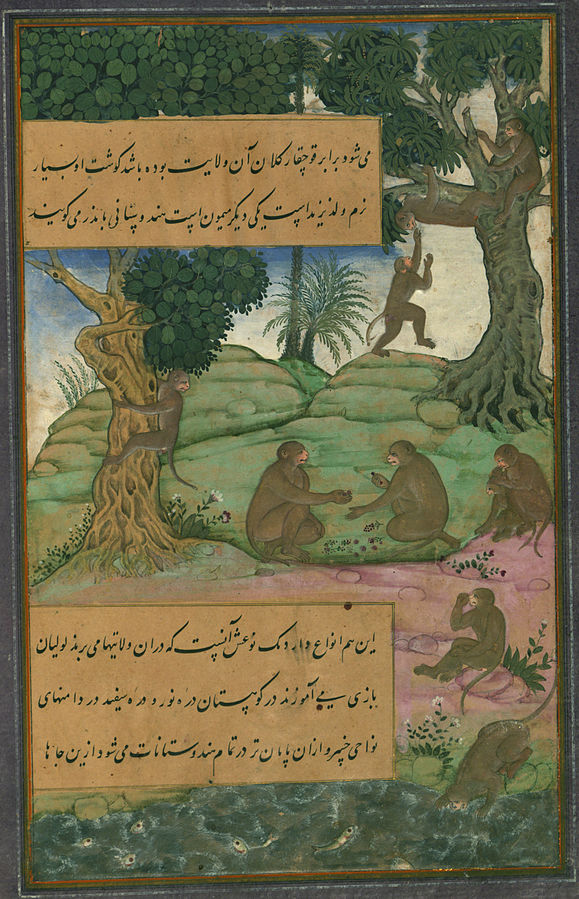

The mesmerizing allure of acrobats, jugglers, and animal performers transcended social boundaries, enchanting royalty, and common folk with their captivating street performances. Delving into historical accounts, the memoirs of Babur provide illuminating glimpses into the dynamic relationship between Hindustanis and their simian counterparts. Monkeys, referred to as “banders,” took center stage as they became participants in the theatrical spectacle orchestrated by skilled jugglers. These performers, wielding a mastery of tricks, imparted a sense of wonder as they showcased the intelligence and agility of their primate companions.

Monkeys that can be taught to do tricks, from the Baburnama (The Walters Art Museum)

Most of these artists are believed to belong to a single community of performers. The umbrella term ‘Madari,’ commonly used to denote street performers often accompanied by animals like monkeys, and bears, carries a profound historical resonance undiscovered to many. Originating from the followers of the 14th-century Sufi saint ‘Shah Madar’ who hails from Syria, the term’s evolution is a fascinating tale. Shah Madar’s disciples, distinctive within the Madarriya order of Sufism, differed markedly from other Sufi groups like the Chishtis or Nimatullahi. Their practices, rooted in syncretism, shared similarities with Naga Sanyasis, involving body smearing with ash and the consumption of hemp (bhang). Renowned for performing extraordinary feats such as walking on flames and executing magic tricks, the adept Madaris dazzled audiences. Those less skilled engaged in performing with animals like monkeys and bears. This diverse range of skills and performances over centuries led to the gradual transformation of ‘Madari’ into a generic term encompassing all jugglers and street performers, echoing the rich historical tapestry woven by the Madarriya order from its Sufi origins to the vibrant streets of contemporary performance art. In William Crooke’s ethnographic exploration, “The Tribes and Castes of North Western Provinces of Oudh,” he classified the devotees of Madar Shah as individuals engaged in a nomadic lifestyle, known for their diverse talents such as entertaining with bears and monkeys, showcasing juggling skills, and demonstrating the daring act of fire eating.

Interestingly, another group named Kalandar, or qalandar, associates themselves with this profession. This group was considered devotees of another Sufi saint Bu Ali Qalandar. Historically, the Qalandar community, originally nomadic, has transformed, with many now adopting settled lifestyles. In North India, a segment of this community took on the role of guiding bears, monkeys, and other performing animals as they meandered through regions, announcing their presence through the rhythmic beats of an hourglass-shaped drum known as a damru. This drum served as a powerful accentuation in their performances. Meanwhile, another significant portion of the Qalandar community established settled lives in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bengal. Despite embracing a more sedentary existence, these individuals retained their ancient mystic religious beliefs, as mentioned by Tejinder Singh Randhawa in his work “Qalandar in The Last Wanderers: Nomads and Gypsies of India.”

The Art of Charmers

The artistry of monkey charmers is an enchanting performance that transcends time and tradition. These skilled performers, known for their enchanting ability to communicate and engage with monkeys, weave a mesmerizing tapestry of entertainment. The monkey charmers do skits narrating stories while the monkeys act as the characters of the story. Through a symphony of gestures, coaxing, and rhythmic beats, they orchestrate a unique dance. To add flair to the performances these artists utilize props and instruments, while also adorning the monkeys with costumes that seamlessly transform them into the characters of the narrated skits. Dialogues and expressions in these street performances mirror the essence found in the dialogues and expressions of characters in iconic Bollywood films. Instead of relying on spoken words, the monkeys utilize head gestures such as nodding, coupled with precise facial expressions, to communicate effectively with the audience.

Monkey performances were a common sight on the streets of Delhi, featuring a troupe typically consisting of two or more monkeys, often comprising one female and two male monkeys. The performer skillfully narrated a storyline accompanied by running commentary, depicting the males’ concerted efforts to win the affection of the female monkey with the ultimate goal of marriage. The female monkey, trained to exude an air of coyness and play hard to get, added a touch of theatrics to the performance. The act concluded with a flourish, featuring dramatic elements and culminating in a symbolic wedding ceremony between one of the male monkeys and the female, bringing the narrative to an entertaining close. The result is a captivating fusion of storytelling and physical prowess, where the monkeys, guided by the skilled choreography of their charmers, become living embodiments of the tales being spun.

Concealed behind the façade of enchanting performances, the monkeys bear the weight of a chain tightly fastened around their necks, connected to a rope firmly gripped by the Kalandars.The charmers wield bamboo sticks, not merely as guides but as tools of coercion, instilling a sense of compliance in their simian companions.

Onlookers watch as an Indian monkey trainer leads a pair of monkeys as they perform tricks on a residential street in Jalandhar on December 25, 2016.

Though banned in India, monkey street performances are a popular form of entertainment in India. Monkeys are protected under the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 which declares that all Indian wildlife is government property and prohibits the capture and possession of monkeys. The monkey performs tricks like shaking hands and dancing for the audience, especially children who in turn give money to the tamer. People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) India claims that monkeys are trained to ‘dance’ through beatings and food deprivation and it is a violation of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972. / AFP PHOTO / SHAMMI MEHRA

The monkeys, compelled by the demands of the charmers, dutifully traverse in circles, collecting the offerings generously bestowed by the audience. These earnings, collected with somber obedience, are then surrendered to the charmers, completing a transaction that belies the whimsical facade of the street performance. Behind the veneer of entertainment, a poignant narrative of coercion and compliance silently plays out, hidden from the spectators’ eyes.

Animal performances beyond monkeys

In addition to the popular monkey and bear performances, snake charmers hold a prominent place on the streets of India. Unlike the lighthearted image associated with monkey charmers, snake charmers often evoke fear, primarily due to the perceived danger associated with snakes.

Snake charming involves the captivating practice of seemingly hypnotizing a snake, often a cobra, through the use of an instrument called a pungi. The roots of this tradition can be traced back to ancient Egyptian sources, where charmers served as both magicians and healers. Their knowledge extended to understanding various snake species, the deities to whom they were sacred, and techniques for treating snake bites. While the origins of snake charming likely lie in India, it has ancient ties to Hinduism, which regards serpents as sacred beings associated with the Nagas, and depicts numerous gods under the protection of the cobra. Early snake charmers were probably traditional healers who specialized in treating snake bites. Under the guidance of figures like Baba Gulabgir (or Gulabgarnath), who encouraged reverence for snakes, practitioners learned not only to handle snakes but also to remove them from homes. The practice gradually expanded beyond its origins, reaching North Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

The Uncharmed Life of the Charmers

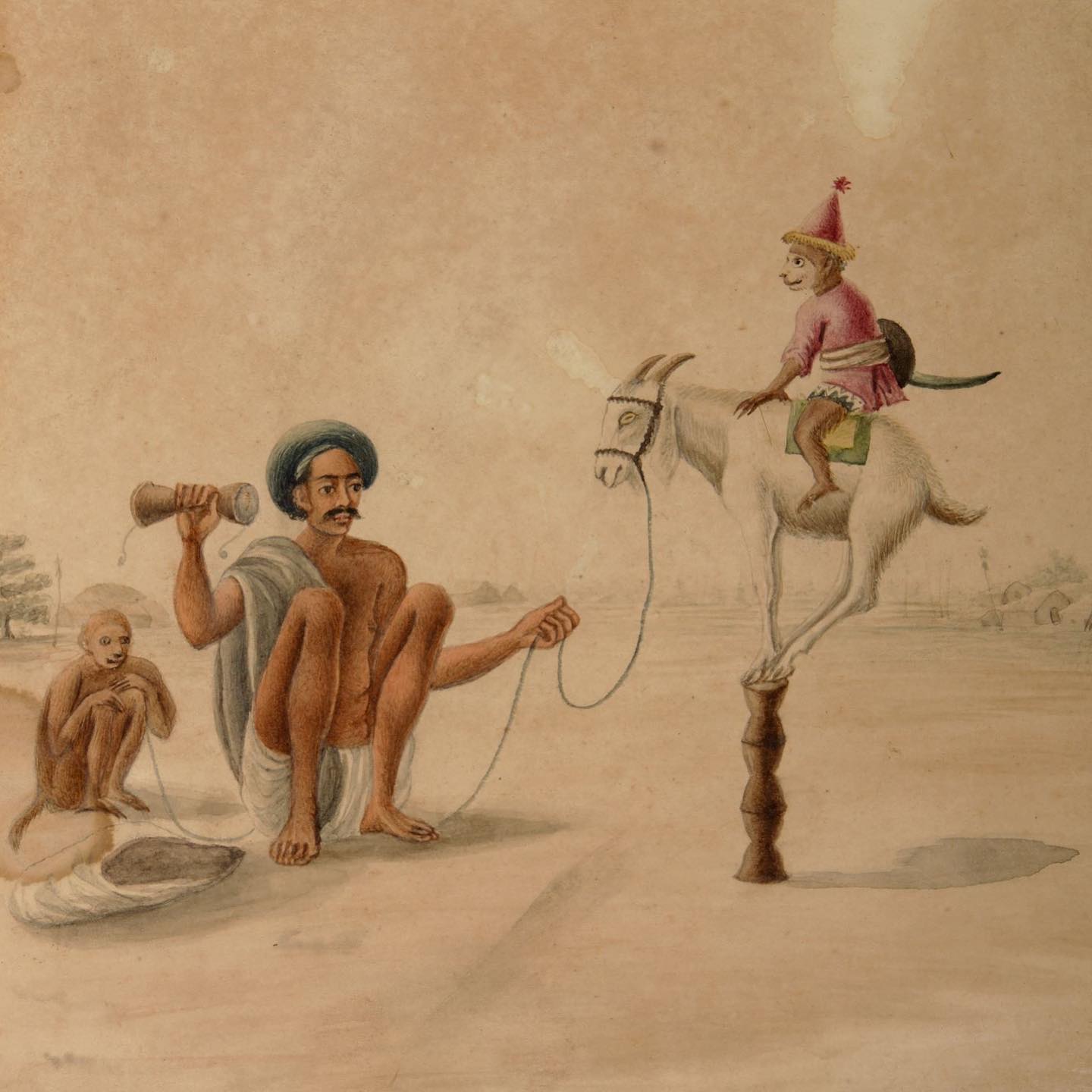

A visual memoir of 19th century portraying a madari with its two monkeys and a goat.(National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi)

The disappearance of charmers and street magicians prompts curiosity, with some attributing their absence to the influence of the British Raj era. Puppet shows and street plays became catalysts for anti-colonial sentiments among Indian sepoys serving the English East India Company. The collaboration of Madari Fakirs with Hindus like Bhawani Pathak and Holkars, presenting a syncretic religious blend, posed a significant threat to the British colonial agenda built on the policy of divide and rule. Formerly esteemed members of the military in the Maratha, Mughal, and Rajput realms, Madaris found themselves branded as enemies by the British. To suppress their influence, the British implemented the Dramatic Performances Act in 1876, curtailing public performances perceived as a form of protest against colonial rule. This act not only hindered public performances but also initiated the enduring censorship of public theatre in cities.

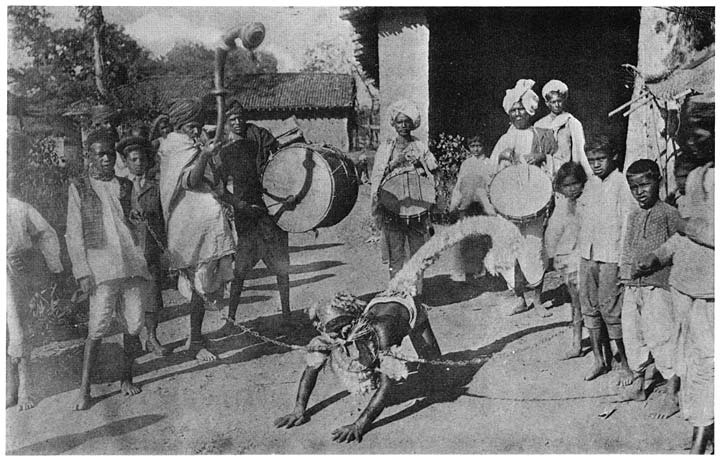

Performance by Madaris in the 19th century (photo by Awaz The Voice)

As a consequence, Madaris faced severe repercussions, including unemployment, criminalization of their profession, and the categorization of various sects among them as criminal tribes. Over time, discrimination pushed them from a position of respect to the marginalized status of ‘Pasmanda.’ The decline of this art form was further accelerated with the introduction of the Wildlife Protection Act in 1972, which prohibited the use of captive wild animals for performances. This dual assault on both performers and their practices marked a significant chapter in the suppression of cultural expressions, leaving a lasting impact on the legacy of Madari Fakirs and Kalandars.

The Last resort

Bound by stringent policies and regulations, these performers found themselves compelled to abandon their traditional profession. Some chose to sever ties with their animal companions entirely, while others sought innovative avenues for applying their unique skills. Transforming their roles, these artists transitioned into becoming monkey chasers. Initially commissioned by the government, their task was to disperse monkeys from government buildings in Delhi.

In the past, langurs were commonly employed to deter rhesus monkeys, their natural adversaries, from infiltrating residential and public spaces in the city. However, in 2012, the Delhi government prohibited the use of langurs due to reported animal cruelty, imposing substantial fines on those exploiting them for commercial purposes. Attempts with trained dogs, scareguns, and electronic devices proved largely ineffective. Consequently, most monkey whisperers found themselves unemployed. Undeterred, they embarked on a journey of self-reinvention, mastering the art of mimicking langur sounds. This unconventional skill set enabled them to successfully drive away monkeys without the need for langurs.

The monkey Whisperer making peace with the monkeys in the movie Eeb Allay Ooo! ( credit – The Wire)

This unusual government job comes with its dangers, struggles, and disillusionment with the work, which is perfectly shown in the movie Eeb Allay Ooo! (2019) featuring the lives of these workers. Interestingly the sound Eeb Allay Ooo is what they make to scare away the monkeys.

Amidst the uncontrolled surge in the monkey population in the capital, incidents of monkeys wandering and posing threats to people have surfaced. Fearing potential disruptions during the G20 summit in Delhi, a considerable number of monkey whisperers were enlisted. To deter the monkeys, cut-out banners resembling langurs were strategically placed on railings. Nevertheless, some speculate that the strained human-monkey connection has led to feral behavior among the monkeys. From the enchanting performances that once graced the streets to the unexpected transformation into monkey chasers, the journey of these artists and animals reflects resilience in the face of societal changes. The intricate relationship between humans and monkeys, once steeped in reverence and storytelling, has undergone a shift, shaped by historical events, colonial imprints, and contemporary regulations.

Reference

- Khan, Enayatullah. “WILD MAMMALS IN MUGHAL SOURCES.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 72, pp. 551-559, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44146750. Accessed 31 Dec. 2023.

- Chavan, Akshay. “The Madaris of India.” PeepulTree, 26 Oct. 2018, www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindia/story/people/the-madaris-of-india.

- Khosa, Aasha. “Madaris Played a Role in India’s Freedom Struggle.” https://www.awazthevoice.in, 19 Sep. 2022, www.awazthevoice.in/culture-news/madaris-played-a-role-in-india-s-freedom-struggle-15752.html.