India’s Dying Record-Keeping Script: The Mahajani

Article By – inika choudhary

Scripts have been the flag bearers of preserving human thoughts and ideas. They materialise our ideas into the written word, such that they can be etched into so much more than just our memory. Several scripts existed in the Indian subcontinent, but they face the threat of extinction today with limited learners and a select few to carry the legacy forward. Today, we come to one such script, The Mahajani, which was used widely in Punjab, Bihar, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

An Introduction to the Script

The Mahajani script is based on the Brahmi writing system, a script that was in use well until the middle of the 20th century all across Northern India. Mahajani is specially used for writing accounts and maintaining financial records and is thus a commercial script. At the height of its use, it recorded several languages like Hindi, Marwari, and Punjabi.

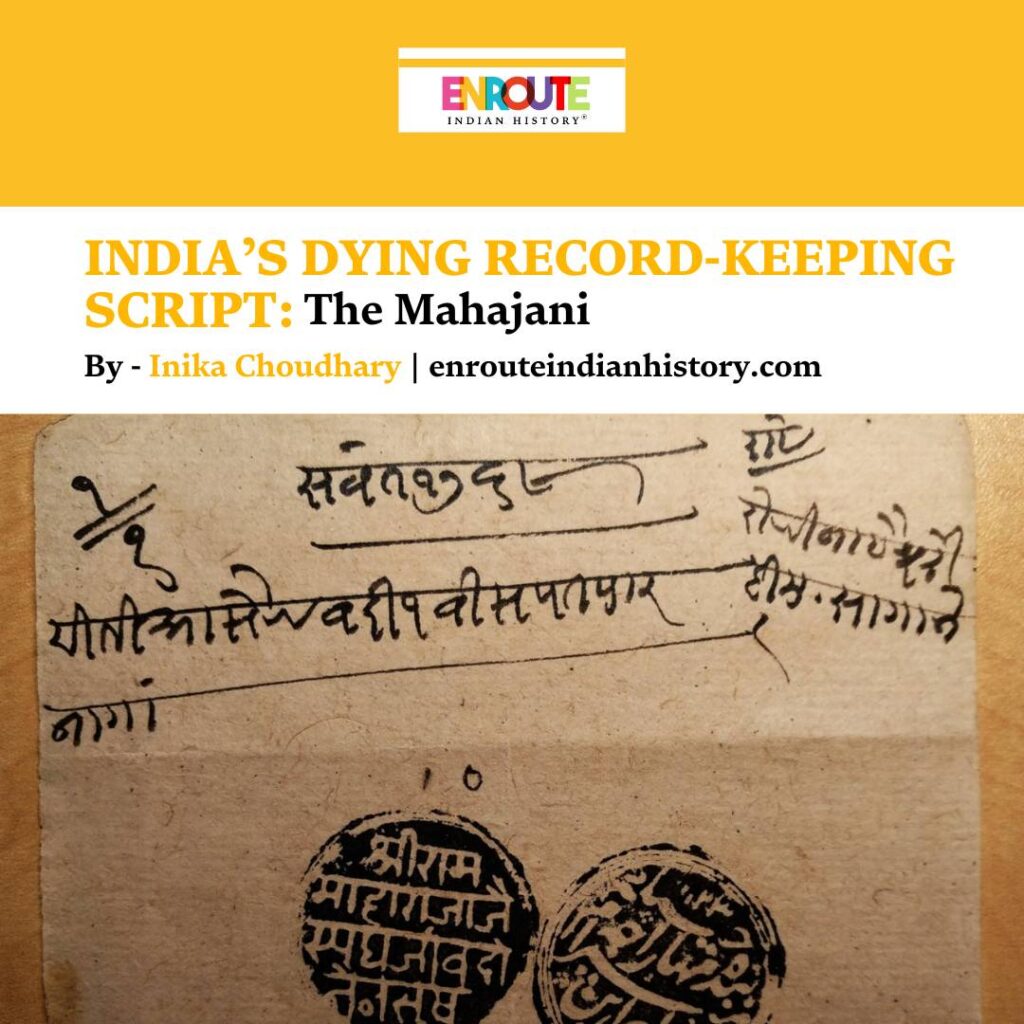

The name Mahajani has been derived from Mahajana, literally meaning bankers and money lenders. These communities were the major users of the script. That is particularly why a large number of Mahajani records are account books, known locally as bahi-khata. We also have examples of other documents like merchant diaries or roznama, financial instruments, bills of exchange (hundi) and finally chitthi, or letters. Many schools, known as chatashalas in North India used to incorporate teaching Mahajani in their educational curriculum, and here, students from merchant and trading communities learned other writing skills required for business as well. Mahajani is also used for writing other scripts when used in commercial activity. ‘Mahajani Dogra’, for instance, refers to a style of the Dogra script used by merchants, which is written in a manner very much like the Mahajani or Landa style. Mahajani is also attached to a Gujarati script as well as to a form of Devanagari in which Marwari and other languages of Rajasthan are written.

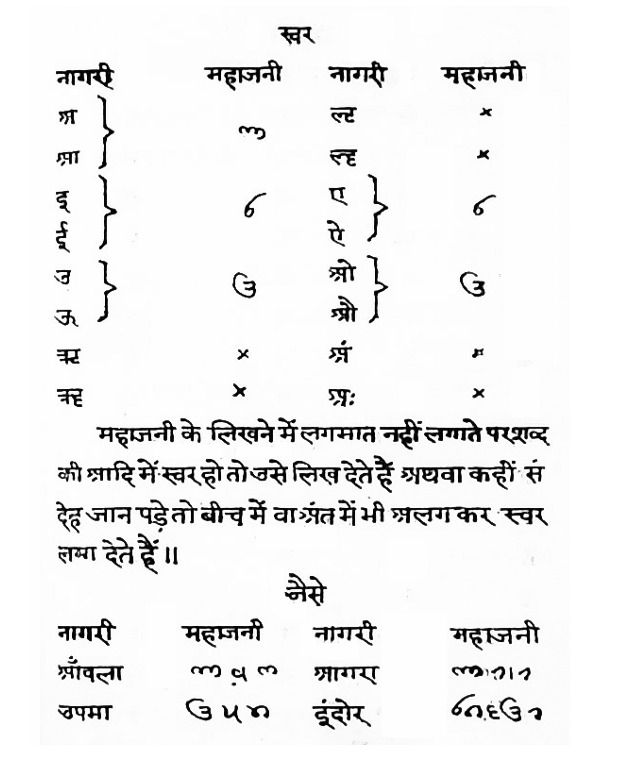

Mahajani is structurally simpler than Brahmi and instead behaves as an alphabet. Here, vowel signs are not used. There is no virama or break used, and the script is written from left to right. Nasalization in the script is explicitly recorded with the letter ‘na’ instead of being represented using special signs like anusvara, and in most cases, it is simply deleted. The nukta is used for allophonic variants and sounds that occur in local dialects, sounds that are not represented by a unique character. Mahajani uses digits similar to those in Gujarati and Devanagari, instead of script-specific digits. Additionally, fraction signs and unit marks are also found, considering how the script was primarily used commercially.

A story is told of a Mathura merchant who was absent from home, and whose agent wrote from Delhi to his family to say his master had gone to Ajmer and wanted his big ledger. The agent wrote, ‘Babu Ajmer gaya, bari bahi bhej dijiye.’ This was written in Mahajani, which usually omits vowels as mentioned earlier, and the result was that the letter was read as ‘Babu Aj’mar gaya, bari bahu bhej dijiye.’ literally translating to, “The master died today, please send the Chief wife!” (Beames, C.G.I., 56)

Govind Agarwal, while commenting on the working of Marwari trading firms, talked of how an essential condition for the appointment of a munim and gumashta was that they should be well-versed in Vanik Vidhya (commercial expertise) and know the Mudia and Mahajani scripts. A compilation of his family papers preserved in the newly established Research Centre of ‘Nagashri’ at Churu shows several documents, bahis (account books), and ledger books written in Mudia, Kamdari, and Mahajani.

Mahajani in The Larger Context of Indian Scripts

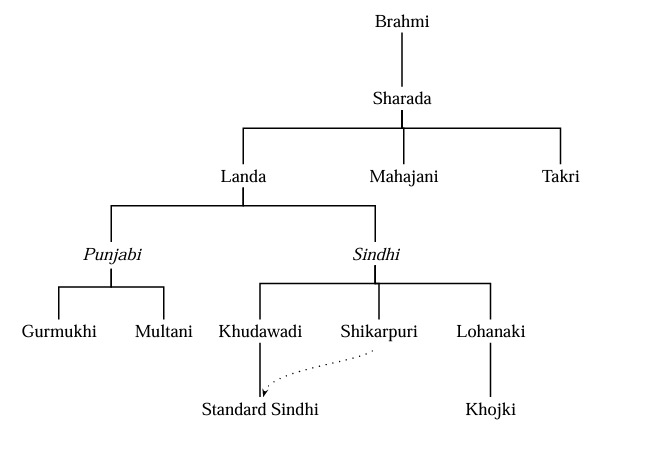

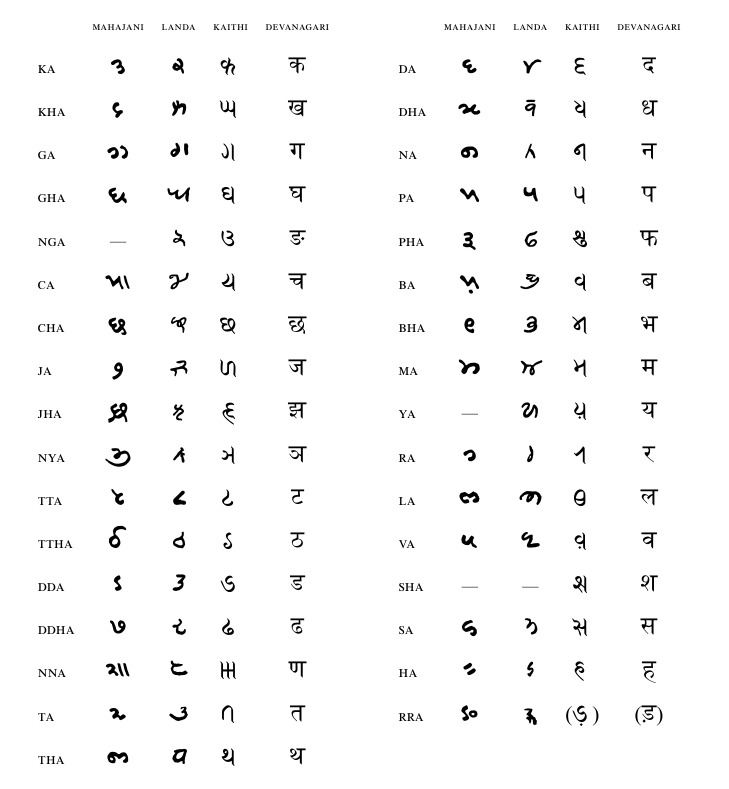

The term landa is a Punjabi term meaning tailless or clipped. The scripts of this family, like Punjabi and Sindhi, bear acute resemblance to Mahajani in orthography and structure. Certain characteristics, like the absence of vowel signs, inattention to word spacing, and an abbreviated repertoire of vowel and consonant letters, etc. make them quite similar. An important distinction can be made here between the glyph shapes of the consonant letters, even though the two scripts have similar glyphs for vowels. Consequently, one can also spot similarities with the Sharada family. Mahajani is also described as a derivative of the Kaithi script or a ‘tachygraphic abbreviation’ of Devanagari. Even then, most letterforms of Mahajani are different from Devanagari and Kaithi, as are its structural, orthographic, and graphical features. It is also similar to other accounting scripts like Sarrafi (sarraf–‘banker’ in Arabic), Baniauti (merchant’s script) and Kothival (merchant).

Several lithographed books dated to the late 19th century have been found for teaching the script. A prominently known instructional manual is Mahajani-sara-hissa avvala-va-doyama written by Lala Gangadasa Munsi Lala in Delhi, roughly in the 19th century. This manual is instrumental in teaching the script, apart from explaining methods of accounting and letter writing. It contains Hindi text in Mahajani, Devanagari, and the Perso-Arabic scripts. We also have the Mahajani-sara written by Srilala in Hindi as a major source of knowledge, dating to 1875 and published in Allahabad. Another text was published by the same author, a supplementary edition in the Devanagari script. Other specimens of Mahajani can be seen in grammar books and script primers, among other materials. George A. Grierson and Samuel Kellogg have also given charts showing the script in A Handbook to the Kaithi Character (1899) and A Grammar of the Hindi Language (1876) respectively. In his book, History of Indigenous Education in the Punjab (1882), Gottlieb W. Leitner talked of numerous specimens of Mahajani as used in Punjab. In his Indo-Aryan Grammar of 1872, John Beames aptly expresses the origins of Mahajani and its relationship to other scripts:

The Mahâjani character differs entirely from that used for general purposes of correspondence, and is quite unintelligible to any but commercial men. It is in its origin as irregular and scrawling as the Sindhi, but has been reduced by men of business into a neat-looking system of little round letters, in which, however, the original Devanagari type has become so effaced as hardly to be recognizable, even when pointed out. Perhaps this is intentional. Secresy has always been an important consideration with native merchants, and it is probable that they purposely made their peculiar alphabet as unlike anything else as possible, in order that they alone might have the key to it. (Beames 1872: 55)

Conclusion

Mahajani finds lesser use in modern-day India, and yet, it is not completely obsolete either. An article in 2004, published in the Tribune, reported on the demise of ‘Langdi Hindi’, a form of the Haryanvi language used specifically for bookkeeping and written in Mahajani. The Mahajani script is an important key to the historical financial records of northern India. The Kayasthas used Kaithi for record-keeping, Modi was used in Maharashtra, and Mahajani was used to record financial and business matters.

The present generation is more or less unaware of this script, resorting to the Devanagari for everyday writing and this pattern of forgetting old scripts has led many of them to the verge of extinction. What we thus need is more attention to be given to India’s dying heritage, so that we can traverse forward whilst keeping the echoes of our past alive.

References

- Pandey, Anshuman. A Roadmap for Scripts of the Landa Family. No. 3766. N3766 L2/10-011R. February 9, 2010. http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs

- Pandey, Anshuman. Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Mahajani Script in ISO/IEC 10646. No. 3930. N3930 L2/10-377. October 6, 2010.

http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs - SHARAN, ANAND M., et al. “ON THE HISTORY OF ORIGIN OF KAITHI AND MANY OTHER INDIAN SCRIPTS.” (2014).

- Devra, G. S. L. “The functioning of a Marwari trading firm (c. 1750–1850).” Studies in People’s History 2.1 (2015): 96-104.

- https://www.omniglot.com/writing/mahajani.htm

- https://www.endangeredalphabets.net/mahajani/

Plagiarism Score: 94% Unique Content

Grammarly Score: 75/100

Image 1: A Family Tree of Landa and Related Scripts, retrieved from “A Roadmap for Scripts of the Lnada Family”, the source being Script Encoding Initiative. Dated 25 January 2010.

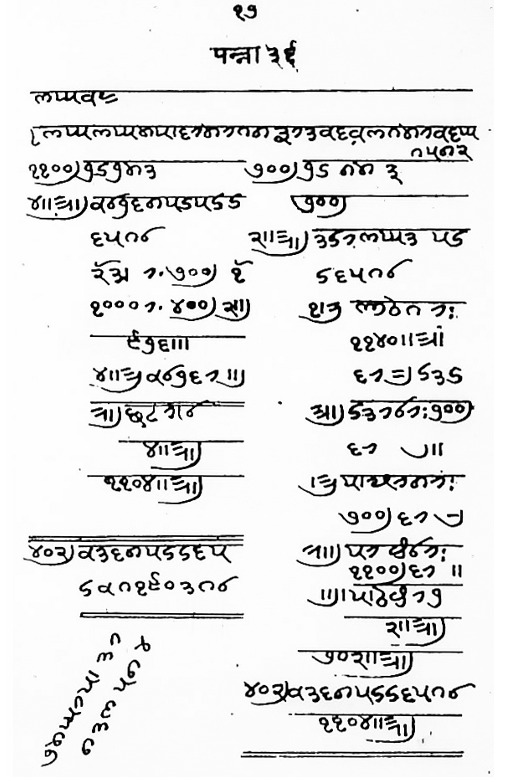

Image 2: A Letter in Mahajani script from 1711, retrieved from a Reddit Post from a user hoping to get it translated.

All the following images are retrieved from “Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Mahajani Script in ISO/IEC 10646. No. 3930. N3930 L2/10-377.” authored by Anshuman Pandey, dated October 6, 2010. (Images 3-6)

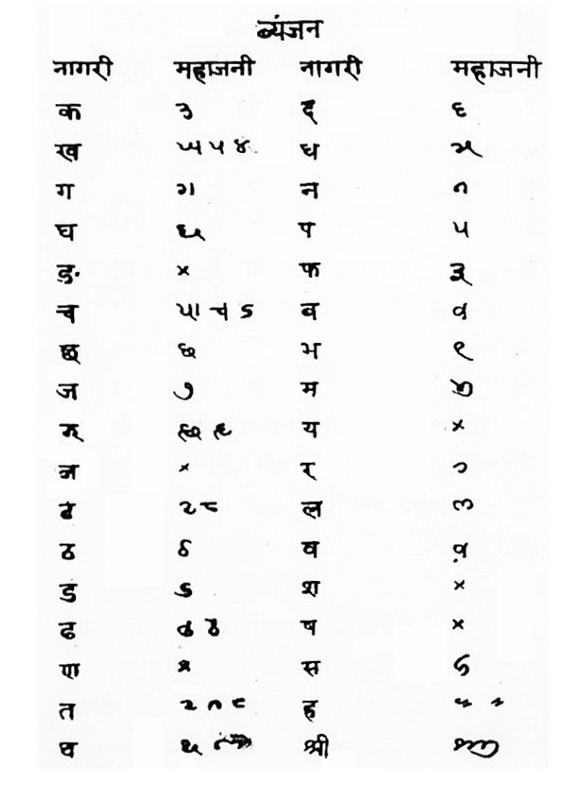

Images 3 and 4: Vowel and Consonant Letters in the Mahajani script, taken from Srilala (1875).

Image 5: Fractions in the Mahajani Script, taken from Srilala (1875).

Image 6: Comparison of Consonant Letters of Mahajani, Landa, Kaithi, and Devanagari Scripts.