Modi Script: Lost Identity of the Spoken Language

Article By – Chanchal Kale

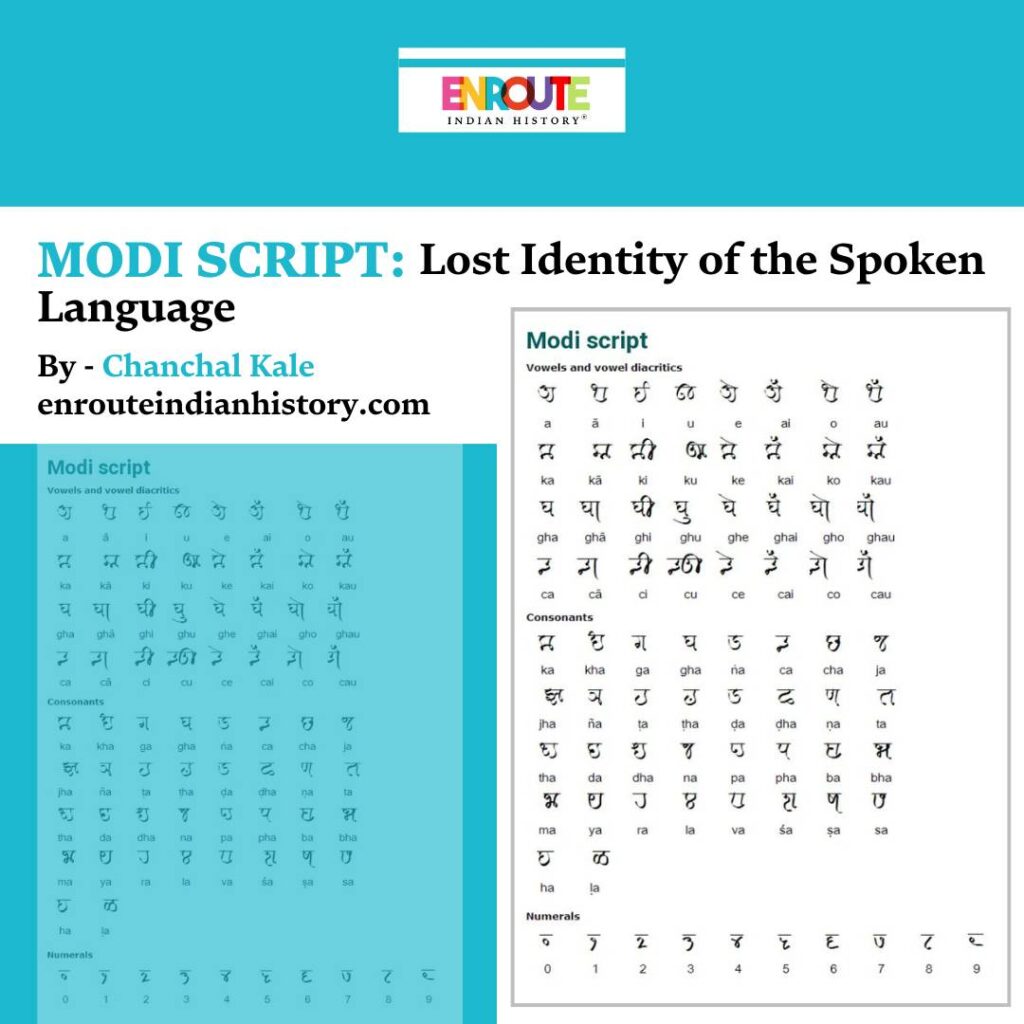

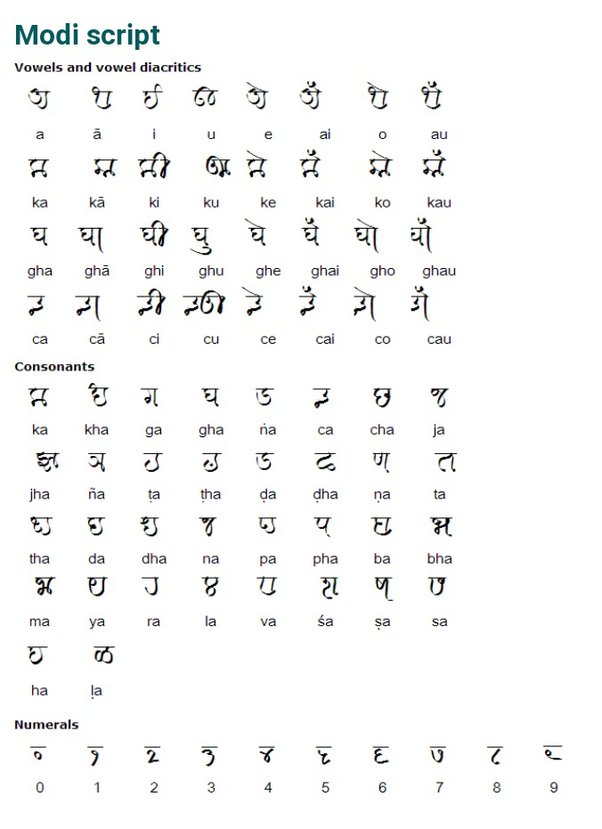

Vowels, consonants and numerical in Modi Script

Introduction

The significance of writing systems in the stabilization of languages, particularly in South Asia, cannot be overstated. Scripts serve as a tangible medium through which literacy is cultivated and access to information is enhanced, enabling civilizations to chronicle their histories and daily occurrences—this is crucial for comprehending the complexities of ancient cultures. Nonetheless, the hierarchy of writing systems and their status remains a contentious issue among scholars. Influential theorists, such as Ferdinand de Saussure, have prioritized spoken language, which has shaped the trajectory of linguistic studies towards oral communication since the mid-twentieth century. As a result, the multifaceted social, semiotic, and political dimensions of writing systems and their relations with the spoken language have often been overlooked in contemporary discourse.

The relationship between spoken languages and written scripts in India was highly dynamic until the emergence of printing culture in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It was common for many widely spoken languages to be represented in multiple scripts, a phenomenon known as “polygraphia.” For example, the Marathi language of the Deccan was conveyed in two distinct forms: the “Balbodh” script, which is essentially the same as Devanagari, and the “Modi” script. Importantly, there was no hierarchical relationship between these scripts, as both were equally accessible to the Marathi literati. However, by the late twentieth century, the Modi script had completely vanished, and its neglect and discontinuation are often attributed to colonial British rule. However, the history of the Modi script, particularly its decline, is nuanced and intertwined with discussions about caste, class, nation, and colonialism, with the Print Revolution playing a significant role in this complex narrative

Historical Overview

The Modi script is a Brahmi-based writing system primarily used for writing Marathi and, in some cases, other languages such as Hindi, Gujarati, Konkani, Tamil, and Telugu. While there are varying theories regarding its origin, most researchers agree that the Modi script is derived from the Nagari family of scripts. Unfortunately, the history of the Modi script, including its origins and decline, is poorly documented.

Traditionally, it is believed that the Modi script was developed by Hemadpant, a prominent administrator in the court of Ramdevrao, the last king of the Yadav Dynasty (1187-1318). However, George A. Grierson (1851–1941), in his Linguistic Survey of India, suggested that it was invented by Balaji Avaji Chitnis, a minister in Chhatrapati Shivaji’s court. Nevertheless, the existence of several documents written in Modi from the sixteenth century, produced under the Deccan sultanates, challenges the notion of a late origin for the script. But certainly, Shivaji can be credited for popularizing the script as the standard written form during his reign in the seventeenth century.

It is believed that Balaji, while attending a Darbar in Delhi, observed that documents for the fast transcription of Persian proceedings in the Mughal court were written in a broken script known as Shikasta, rather than the clearer but slower Nastaliq script. Recognizing the importance of speed in administrative affairs, Balaji introduced the Modi script into the Maratha administration. The name of the script, which signifies its purpose, is derived from the Marathi verb “modane,” meaning “to bend or to break.”

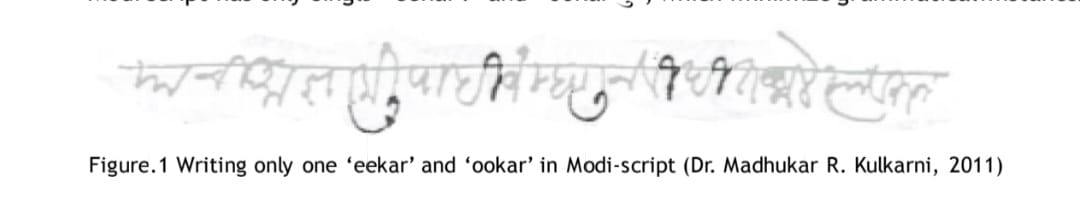

Devnagari characters involve sharp angles, horizontal and vertical lines which minimizes writing speed. To avoid this drawback Modi characters are shaped into circular forms. The script has only a single “eekar” and “ookar,” which helps minimize grammatical mistakes. A complete “header line” is drawn before writing and clerks wrote in a continuous stream without leaving gaps between the words, which practically prevents the writer from lifting their hand. One of the distinctive features that differentiate letters in Devnagari and Modi is that strokes in Devnagari are drawn from top to bottom, while those in Modi are drawn from bottom to top. In essence, the Modi script is a highly cursive alternative to Nagari.

The majority of Modi documents consist of official letters, land records, and other administrative documents. However, there is also evidence of literature written in this script, with notable examples including Veer Savarkar’s famous book “Maajhi Janmthep” and the song “Jyotstute.”

Early printing attempts in Modi scripts succeeded in 1807, when Charles Wilkins created the first metal font for the Modi script in Calcutta. Significant works, such as “Raghu Bhoslyanchi Vanshavali,” were printed in Modi, along with a Marathi translation of the “New Testament” using the same script.

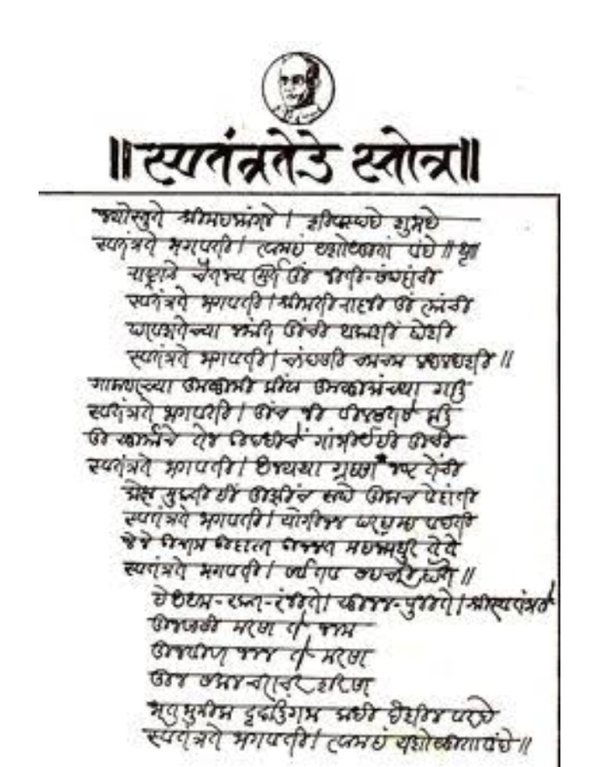

Jyotstute written by Veer Savarkar in Modi Script

Tracing it’s Decline

Handwritten administrative documents in Marathi were primarily written in the Modi script due to its faster transcription speed. In contrast, religious scriptures and high literature in Marathi necessitated precise pronunciation, leading to a preference for the Devanagari script. Evidence indicates that Modi was more commonly used, as noted by J. G. Covernton as late as in 1906.

By the early twentieth century, the debate over whether Marathi should be printed in Devanagari or Modi had persisted for over fifty years, with printing technologies being central to many discussions. The ontological status of Modi was generally accepted; however, the dialogue primarily focused on the advantages of using Devanagari in print media. Despite this, Modi continued to be used for most handwritten correspondence and documents.

The discussion surrounding the use of a unified script for the Marathi language became significant mainly after the introduction of printing, influenced by rapidly evolving social and political contexts. Within a span of just 150 years, Devanagari triumphed over Modi. Scholars have pointed out three primary justifications employed by the colonial authorities to dismiss Modi.

- The initial argument revolved around printing type, emphasizing the legibility and cost-effectiveness of Devanagari.

- By the close of the nineteenth century, matters of social upliftment for the literati and administrative efficiency were central to the debate.

- At the onset of the twentieth century, the British government in India began initiatives aimed at undermining nationalist movements in western India, especially among Marathi speakers, by eroding the more subtle forms of sovereignty represented by the Modi script.

The primary goal was to weaken the power of the clerical and upper castes from the Peshwa era. Arguments based on sectarian lines were thus employed to advocate for Devanagari, tapping into divisions related to language, religion, and caste.

Pushkar Sohoni argues that there is a common misunderstanding that the end of the Modi writing system is connected with the British colonial rule in India. Ironically, the demise of the Modi script was a result of nationalist policies of forcing a culturally unified Indian union, and instituting a state where Marathi became the official language with a single script.

Benedict Anderson in his work “Imagined Communities” (1983) intertwine the role of printing capitalism and rising nationalism across the world. The proliferation of newspapers and novels allowed for the dissemination of ideas across the region’s fostering a shared identity among people who had never met. This sense of “Horizontal Comradeship” was achieved by Print capitalism as it created a unified field of exchange and communication above all the spoken vernacular. Print capitalism created languages and scripts of power, different from older administrative vernacular.

Creating the sense of identity for the linguistic ‘imagined community’ centred upon the use of Devnagari was important. Nationalist movements and local historians in the Marathi-speaking regions were catalysts in such narratives, and the dissolution of a writing system that could visually signify a separate identity was not entirely a coincidence.

A nationalist camp that included B. G. Tilak was in favour of Devanagari being used as the national script for all languages across India to unite the country. At the 1905 Nagari Pracharani Sabha in Varanasi, he urged a common script for a united India. It was this nationalism that would lead to several attempts at creating a national language and writing system.

In June 1949, the Bombay government established a committee headed by Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar to recommend script reforms for Gujarati and Marathi—two languages prevalent in the state. The goal was to simplify printing, typing, reading, and writing in these scripts while ensuring they met the fundamental requirements of a scientifically sound script. As anticipated, the committee’s recommendations favoured the Devanagari script for Marathi, aligning with the vision of a national script to bridge linguistic divides.

The Report of the Official Language Commission (1956) advocated for the use of Devanagari across all languages in India, especially for languages derived from Sanskrit, such as Hindi, Bengali, Marathi, and Gujarati, and cited Nehru to support its stance. Consequently, the teaching of the Modi script was abruptly halted in schools starting around 1959, and students began learning Marathi exclusively in Devanagari.

Revival Projects

Modi is significant because studying Maratha history is impossible without understanding it. A large number of documents and correspondence from before Shivaji’s time are written in this script. Approximately four crore Modi documents from the Peshwa records are housed at the Pune Archives.

Mandar Lawate, an expert in Modi at the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal, emphasizes that Modi should not be taught solely as a research script. Many old village records were maintained in Modi, and it remains crucial for people to access these records for legal purposes. He expresses concern about exploitation, as individuals have to pay Rs 2,500 to have a single page transcribed.

There is potential for reviving the Modi script by utilizing appropriate technology to make it more accessible. In recent years, several scholars, including Rajendra Thakare, have initiated efforts to revive it. Thakare presented a paper titled “Reviving Modi Script” in 2014 at MIT Pune, with the project aiming to standardize the Modi script and create a usable typeface.

To promote the ancient Modi script of Marathi, the Vijay Nagar Primary Zilla Parishad school in Satara’s Man taluka has launched a unique initiative to teach it alongside Balbodh, a variant of Devanagari used to write Marathi.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the Modi script was connected to the broader practices of Islamic chancelleries and relied heavily on the technology of paper, which was introduced across South Asia during the thirteenth century. According to Lawate, this type of script allowed officials to produce multiple copies of a document when necessary. However, with the advent of technologies like the printing press, typewriters, and carbon paper, duplicating documents became much easier.

Nevertheless, the Print Revolution was not the sole factor contributing to the decline of the Modi script. Colonialism, and particularly the rise of nationalism, played significant roles. In the effort to establish a unified script for India, many local vernacular scripts were phased out.

The discussion evolved from concerns about technical issues, administrative convenience, or nationalistic suppression. Instead, it became increasingly focused on creating a new national identity that sought to minimize linguistic differences, often at the expense of local cultural heritage.

Bibliography

- Rakesh A. Ramraje, “HISTORY OF MODI SCRIPT IN MAHARASHTRA”, Global Online Electronic International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (GOEIIRJ), Volume-II, Issue-I June 2013

- Rajendra Bhimraoji Thakre, “Reviving Modi-script”, paper presented at MIT Institute of Design, Pune, India, 2014, https://www.mitid.edu.in/paper-on-reviving-modi-script-by-asst-prof-rajendra-thakre-in-typography-2014/

- PUSHKAR SOHONI, “Marathi of a Single Type: The demise of the Modi script”, Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 24 C Cambridge University Press 2016 doi:10.1017

- ROBIN JEFFREY, “India’s Newspaper Revolution Capitalism, Politics and the Indian-Language Press, 1977-99”, published in the United Kingdom by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 38 King Street, London, 2000

- https://www.quora.com/What-led-to-the-downfall-of-Modi-%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%A1%E0%A5%80-script-in-which-Marathi-was-written-before

- https://thebetterindia.com/147177/news-history-letter-shivaji-coronation-satara/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20letter%20is%20written%20in,within%20minutes%2C%E2%80%9D%20he%20added

- https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/maharashtra-village-school-seeks-to-revive-ancient-modi-script-9208518/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pune/band-of-researchers-enthusiasts-strive-to-keep-modi-script-alive/articleshow/30761335.cms

- https://modi-script.blogspot.com/2008/05/history-of-modi-script.html?m=1