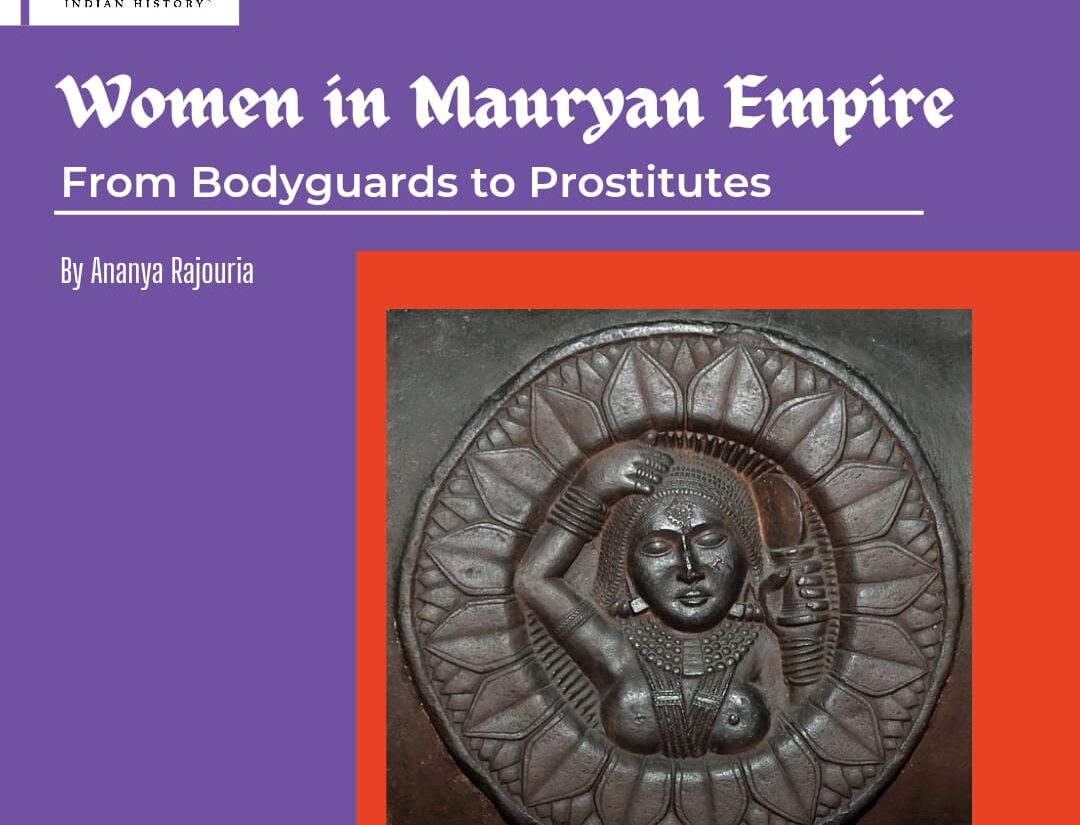

Women in Ancient Indian society have mostly stood as silent figures. While the names of some queens of Ancient India might have surfaced on the pages of your history books, women’s rights and roles belonging to the common populace in ancient Indian society are generally restricted to marriage. However, The Mauryan Empire stands as an exception to this norm. Sources such as the Arthashastra of Kautilya and the writings of the Greek travelers provide us with scattered evidence and piecing the data together frames a vibrant picture of women’s rights and roles in the Ancient Mauryan empire. Although the ideal and primary function of women remained getting married and producing offspring, there were other aspects to their lives as well. These ranged from being espionage to being a Ganika, skilled archers to personal slaves, and at times ascetics.

Kautilya’s Arthshastra informs us that a girl child becomes known to society at the age of 12. According to the Arthshastra, It is at this age when a girl attains maturity or Vyavahara and must be married. The writing of the Greek traveler Megasthenes in his work Indica describes that women in the Mauryan Empire were married at the age of 7 and became old at the age of 40. However, it is interesting to highlight that while Kautilya’s Arthshastra follows all the moral guidelines, it occasionally grants women the right to remarry (Bk III; Ch II & IV). For instance, If a husband is a Brahmin, studying abroad and not heard of, then the wife must wait for ten years, and if a mother then twelve years. After that, she is allowed to remarry. However, in most cases, remarriage was only allowed to the husband’s brother.

It is ironic that in the Mauryan empire, women were at times the most trusted bodyguards. While on other occasions, Kautilya warns a king to be beware of his queen. Arthshastra states that after rising from his bed, the king is protected and taken care of by a troop of women archers termed Striganairdhenvibhih (Bk I; Ch XXI) their role was to act as the bodyguard of the King. Even the Greek writer Megasthenes also corroborates the fact that women in ancient India used to carry weapons with them. He describes women accompanying the king to hunt in chariots, on horseback, and elephants equipped with bows and arrows. However, whether these women archers in the Mauryan Empire belonged to the same caste or whether or not they also were slaves in the royal palace is unknown. The women of the royal family in ancient India along with their female slaves and attendants occupied the Antahpura or Harem. Kautilya warns a king of his safety in the harem by citing examples of the kings who were assassinated by their queens (Bk: I; Ch: XX). Everything that went inside the Antahpura and came out was ordered to be carefully inspected to prevent any threats to the king’s life. These women along with their slaves and attendants staying in the Antahpura were also prohibited from any contact with the wandering ascetics and slaves from outside the royal premises.

A woman horse rider holding a sacred standard in procession with her face covered with armor. Sculpture from Bharhut Stupa 2nd c.BCE

For a woman in Ancient India, worldly life was considered an ideal path. Arthshastra warns a woman from leading an ‘independent life’ or following a path towards asceticism. However, despite these restrictions, Megasthenes informs us that in the Mauryan Empire, certain women abstained from sexual pleasures and pursued philosophy. The Arthshastra speaks of two types of ascetics. Firstly, Parivrajikas or women of the Brahmana caste and widows. The second group involved Bhiksukis, these were either women who had their head-shaved known as Munda, or heretics belonging to sects like Jainism and Buddhism. For Kautilya, these women made excellent spies as they had no travel restrictions and were often employed to keep an eye on a state official. However, inducing a woman to renounce her home and adopt an ascetic lifestyle was punishable in the Mauryan empire. For women, on the other hand, it served as a path free from gender and caste exploitations.

The Metropolitan Art Museum; A Standing Female deity figurine of

the Mauryan Period

Many of the women worked in the weaving and spinning industry. In the Ancient Indian Mauryan empire, the industry of weaving and spinning proved to be of pivotal importance to women. The industry of spinning and weaving of the Mauryan Empire is described in the Arthshastra’s chapter on Sutradhyaksa. Ancient Indian women skilled in handicrafts were termed Silpavati. However, women’s roles and rights were not equal in the industry. While women like Prositas (women deserted by upper caste men), widows, matrkas (old prostitutes), and devadasis worked in the yarn house. On the other hand, some upper caste women did not leave their households and earned livelihoods by spinning yarn at their own homes. Such women were termed the Aniskasini.

The duty of the Sutradhyaksa was to provide them with work at their homes by delivering yarns and textiles through their dasis. However, if the Aniskasini did come to the yarn house, the exchange of goods and wages was mandatory to be done in the dim light of early dawn. Arthshastra states that the honor and chastity of women working in the weaving sector must be protected at all costs. In this regard, it states that anyone looking at the face of the women workers was punished to pay a fine. Often some women were found guilty of some offense and were sentenced to pay off in the form of personal labor. Women’s rights to their share of wages were upheld by the Mauryan Empire as all the women working in the royal factory received payment without delay. However, at the same time failure to attend to one’s duty at the factory was met with punishment.

Women’s role in the economic sector of the Mauryan Empire was not limited only to the weaving industry. Some women were employed in the agriculture sector. Prof Suvira Jaiswal states that Kautliya is probably the only author to mention the Ardhasitikas of ancient India. These were women tenants tilling the land for half the produce and while usually in the case of other households, the wives were not held accountable for their husband’s debt. The Ardhasitikas on the other hand based on their involvement in the economic produce were held responsible for the loan taken by their husband with or without their assent. Apart from these roles, women were employed as slaves in the King’s palace. Megasthenes mentions how the King in the Mauryan Empire is always surrounded by a crowd of dasis, who tend to his services which include bathing, holding jars, and serving wine. Arthshastra also assigns importance to such slaves for the King’s service and mentions Bandhakiposakas, these were women who were pledged and bound to the establishment to render their services in ancient India. However, Arthshastra states that if a female slave gives birth to a child from a union with her master, it would result in her liberty from bondage.

GANIKAS IN THE MAURYAN EMPIRE.

A substantial percentage of women in Ancient Indian society were Prostitutes. Arthshastra of Kautilya does not shy away from this institution. An entire chapter is devoted to the duties of Ganikadhyaksa or Superintendent of Prostitutes. Among the various terms, Ganika and Rupajiva are the two most repeatedly used for Women’s roles as prostitutes in ancient India. However, there was a difference in the status and payment of the two. Ganika is referred to as “a woman who belongs to a community and whose charms are the common property of the whole body of men.” their institution was divided into three levels- Royal, City-level, and the one under the control of a private organization or person. While all the Ganikas were obliged to visit the Mauryan King’s court, those who were employed in the King’s service were ranked based on their beauty and accomplishments. Women’s role as the king’s servants was to entertain men at the command of the king. Refusal of the same was met by a harsh punishment of one thousand strokes by whip or a fine of five thousand panas. Indicating a complete loss of a woman’s right to her bodily autonomy (Bk II:27.9). A Ganika from the age of 8 was obliged to hold musical performances before the king. Rupajiva on the other hand accompanied traders along the way in a military camp when the army was on march.

Bihar Museum, Patna; Didarganj Yakshi sandstone sculpture from the Mauryan period. Debatable to be a Ganika as she is holding a chowrie or fly whisk which was used by the Ganikas in service of the king.

The royal Ganikas were paid 1000 panas and the Rupajivas were paid half of their income. However, all of them were obliged to submit an account of their daily earning, expenses, and future income. A Ganikadhyaksa was in charge of determining the earning and expenditures of every Ganika and preventing them from being extravagant. Accordingly, the Mauryan Empire levied taxes on them that amounted to twice their earnings in a single day. Thus, the woman’s role as Ganika and the institution of prostitution was an important factor in social history and an economic pillar of the state as it amounted to 30% of its income through tax. One of the other duties of the Ganikadhyaksa was to appoint a Ganikanvaya or a Ganika woman who doesn’t have children but adopts a minor girl and brings her up as a Ganika. In the case of the absence of a Ganika, a Pratiganika is appointed to fulfill her duties.

Alamy.com; Terracotta figurine of a dancing woman from the Mauryan Period, recovered from Bulandi Bagh, Patna.

The Mauryan Empire considered Ganikas as the state’s treasure and their ransom price was fixed at 24,000 panas. In return for the services offered by the Ganikas, the state provided them with protection. Any form of violence against the Ganika was met with the highest form of punishment and a fine double the amount of ransom. The state also employed teachers for their training in necessary arts such as singing and dancing. The sons of these women were trained to become Rangopajiva or Public actors. The importance of these Ganikas was also released in the administrative services, they were the masters of several languages and were an asset to the institution of espionage. The Arthsahstra states that the prostitute spies in the garb of a chaste woman and tests the loyalty and purity of ministers appointed by the Mauryan Empire.

When a Ganika became old, she was appointed as a matrka or nurse to other Ganikas and even worked in the weaving industry of the Mauryan Empire. In matters related to the inheritance of property, after the death of a Ganika, interestingly the first nominee was her daughter. In case she does not have one, then the property was passed on to the mother and an absence of both led to the confiscation by the Mauryan empire. The son had no say in the inheritance of a Ganika’s property. In her lifetime, a Ganika can restore her liberty by paying the ransom amount of 24,000 to the government. While such instances as one can assume must have been rare occurrences in Ancient India. The Mauryan Empire, however, did not consider a Woman’s role as a prostitute, a reason to outcast them. Women’s rights in ancient India were curtailed, but they still constituted a prominent section of society.

An insight into these different aspects of a woman’s life in ancient India reveals that for some of them, lives consisted of things other than marriage. A woman’s role and rights in the Mauryan Empire were diverse but subjected to her class, caste, and proprietary status. There were distinctions based on which role would be appropriate for a woman of a particular caste.

REFERENCES

G. Kuppuram, (1979) ‘CHANAKYA ON PROSTITUTION (Based on Arthasastra)’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 40pp. pp. 215-219. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141963

S. Das, (1939) ‘THE POSITION OF WOMEN IN KAUṬILYA’S ARTHAŚĀSTRA’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, pp.537-563. Available At: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44252408

S. Jaiswal, (2001) ‘Female Images in the Arthasastra of Kautilya’, Social Scientist, 29(34th ed.), pp. pp. 51-59. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3518338

- April 18, 2024

- 5 Min Read

- April 18, 2024

- 7 Min Read