Red Fort

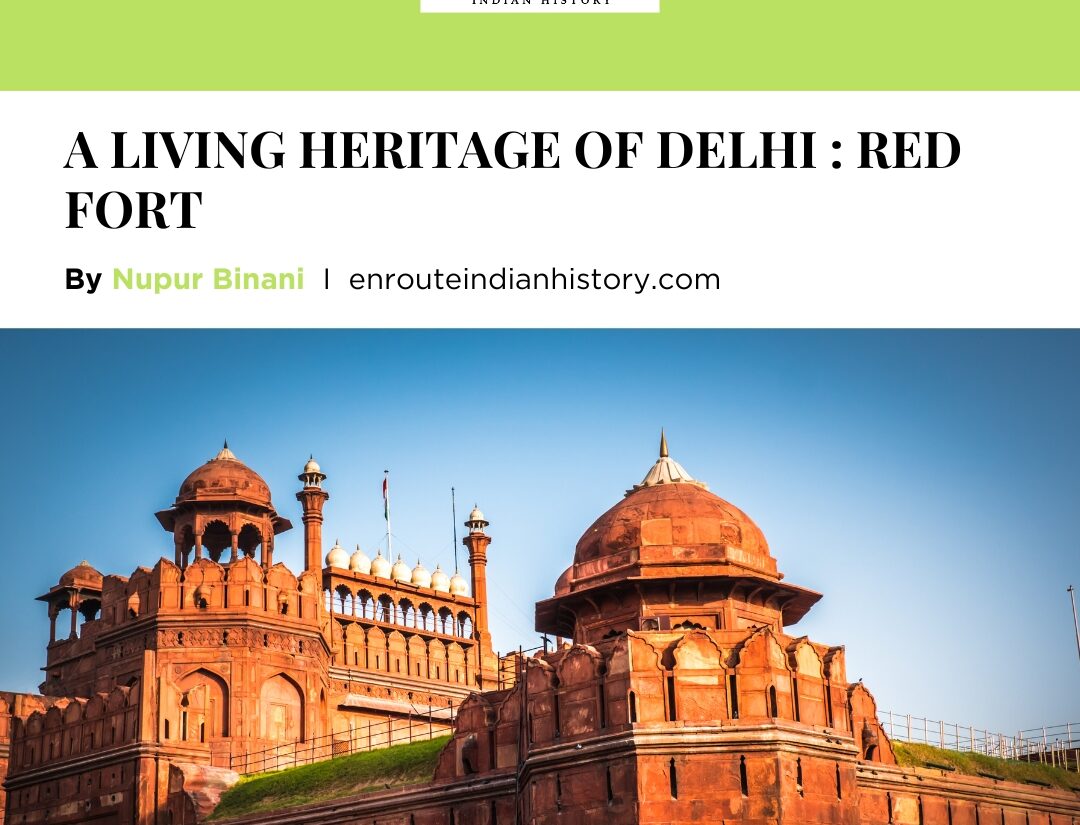

As you step out from the bustling lanes of Chandni Chowk, you encounter a magnificent sight- A huge red building with an Indian flag waving atop it. Huge crowd surrounding the monuments proudly claims it to be “Lal Qila”. Bedecked like a bride, replenished in all its glory, Red Fort is once again in news for the celebration as India hosts the 46th UNESCO World heritage session.

One of the most visited historical places of India is Red Fort, also called Lal Qila and Qila-i-Mubarak (the Blessed Fort), is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The fort was built over a period of 10 years

(1638-1648) accommodated the Royal Mughal family. Shah Jahan, often referred to as the “engineer king” due to his astute understanding of architecture, had a preference for using marble rather than sandstone in his constructions is the man behind the living heritage of Delhi – Red fort located in the new Mughal capital, Shahjahanabad.

Notably, the Red Fort stood out as a pinnacle of architectural brilliance and served a dual purpose as a formidable defensive stronghold. Strategically situated on the banks of the Yamuna River, the Red Fort occupied a central location in Delhi, providing natural fortification against external threats. The river played a crucial role in transportation and climate, making Delhi an ideal choice. Interestingly, the Red Fort had a water gate through which the emperor entered the fort from the Yamuna. Recently, due to overflowing Yamuna, floodwaters surrounded the Red Fort once again. This event sparked discussions about the river’s history and its changing location over time, impacting Delhi’s expansion.Mughal-era paintings depict the Yamuna flowing alongside the Red Fort, emphasizing their historical connection. In essence, the Yamuna has been intertwined with the Red Fort for centuries, shaping the city’s heritage and cultural significance.

Furthermore, its location along important trade routes made it a crucial hub for trade, commerce, and governance. Shah Jahan’s decision to return to Delhi and build this new city was motivated by the challenge of creating a majestic ceremonial pathway amidst the chaotic and disorganized city of Agra. The establishment of this new capital served two primary objectives: it showcased Shah Jahan’s sophisticated architectural taste and displayed the opulence of an empire at its zenith. In this ambitious undertaking, Shah Jahan had ample resources at his disposal, both in terms of finances and labor, within his flourishing realm. On April 29, 1639, at an astrologically auspicious moment, Ghairat Khan, the Subahadar of Delhi, entrusted the renowned builders Ustad Hamid and Ustad Ahmad with the task of constructing the new capital, underscoring Shah Jahan’s unwavering commitment to architectural perfection.

The Old Delhi, earlier known as Shahjahanabad has an interesting mughal history. When the mughal emperor, Shahjahan decided to move the capital from Agra to Delhi in 1638, the emperor gave orders to build his “paradise on earth” on the banks of the river Yamuna, just like the Taj Mahal. This was the first Mughal palace fort designed according to an octagonal grid pattern, primarily made of brick, clad with sandstone or red marble representing a harmonious fusion of Persian, Timurid and Indian elements, yet it is based on Islamic prototypes. The unique style was also distinguished by its complex geometric compositions. The fort is 16 meters on riverside and 36 meters on townside; two entrances allowed access to the citadel: the Delhi and Lahori gates. The first was used by soldiers and servants of the court. The second, facing the town of Lahore and giving onto the Chatta Chowk (palace market) was reserved for visitors and the emperor himself. A wide north-south road ran alongside the market.

Diwan-i-Khas, designated for public and private purposes where the emperor came passing Naubhat khan which was a three-storey rectangular building for the musicians. More than 100 rubies and emeralds enhanced the splendor of the two peacock effigies standing behind the royal seat, as well as countless diamonds, sapphires and rare pearls in Diwan-i-khas.

Like the Diwan-i-khas and Naubhat khan, there are numerous magnificent architectures inside the splendid building creating a perfect blend of islamic art with original hindu art & architecture of India.

The Khas Mahal was part of a series of royal pavilions in white marble giving onto the Yamuna, linked one to the other by a channel whose sparkling waters justified its name of Nahr-i-Behisht, the stream of paradise which had private rooms, prayers room and a tower from where king could address his citizens.

Moti Masjid, the Pearl Mosque, built in 1659 was white marble mosque’s prayer room floor inlaid with the outline of a prayer carpet in black marble. To the north of the mosque is laid out the splendid Hayat-Baksh Bagh, the life-giving garden, its sections also separated by water.

The imperial private apartments that lie behind the throne consist of a row of pavilions that sits on a raised platform along the eastern edge of the fort. The pavilions were connected by a continuous water channel, known as the Nahr-i-Behisht, or the “Stream of Paradise”, that runs through the center of each pavilion. The water is drawn from the river Yamuna, from a tower, the Shah Burj, at the north-eastern corner of the fort.

The two southernmost pavilions of the palace are zenanas, or women’s quarters: the Mumtaz Mahal (now a museum), and the larger, lavish Rang Mahal, which has been famous for its gilded, decorated ceiling and marble pool, fed by the Nahr-i-Behisht. To its north lies a large formal garden, the Hayat Bakhsh Bagh, or “Life-Bestowing Garden”, which is cut through by two bisecting channels of water. A pavilion stands at either end of the north-south channel, and a third, built in 1842 by the last emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, stands at the center of the pool where the two channels meet.

The Islamic city, as described by Thomas Krafft, adheres to a formal pattern featuring a centrally located Friday Mosque, a surrounding marketplace, distinct social and economic zones from the city center to its outskirts, an irregular street layout, city walls, a citadel, inner urban districts, and narrow dead-end streets as typical elements. Islamic Shahjahanabad, this central point was occupied by the Palace Fortress. Jamal Malik suggests that the creators of Shahjahanabad crafted an architectural representation of what has often been referred to as the “patrimonial system”. However, Narayani Gupta clarifies, while Shahjahanabad may exhibit the predominant form of a Mughal city, its way of life and character was predominantly shaped by its residents.

The long drawn Muslim rule does associate Red fort with their tenure but Since its construction, the fort has undergone much modification, the British in particular considerably changing its structure. In 1857, when the British crown took command of the Raj, it made the fort the British Indian Army’s headquarters. As a result, pavilions were torn down and colonial style military buildings replaced them, while Mughal gardens were transformed into English ones. Today, neither as Mughal property nor of Britihsers; The Red fort is under Government of India flying Indian Tricolour flag high on it as a Tourist site. The Prime Minister gives his Independence Day speech on this historically significant site and we should not forget how Hindus and Sikhs connect themselves with the historic monument. In 1947, after India declared its independence, the Indian army took over the Red Fort and turned it into the symbol of the British colonial power’s defeat.

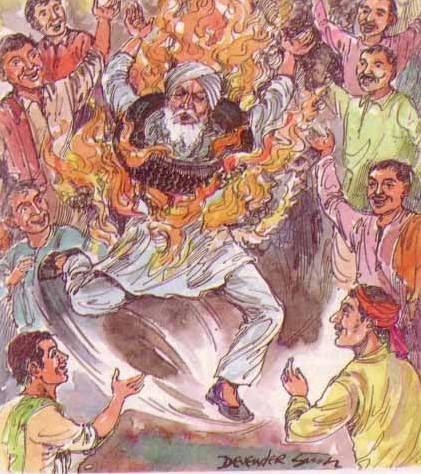

Muslim legacy often overlooks the consequences and collective memories that most non-Muslims associate with these great monuments. Textbooks have generally de-emphasized the negative aspects. It is from Lal Qila, Sikh history tells us, that Mughal emperors deployed their might to subjugate the Indian subcontinent, and from there emanated the power wielded by their dominions. Aurangzeb levied the jizya tax on Hindus and Sikhs for enforcing Islam as the law and religion of his empire. According to Sir Jadunath Sarkar, “the conversion of the entire population to Islam and extinction of every form of dissent.” He galvanized all his religious and secular powers to convert Hindus and Sikhs. On November 5, 1675, the following three devotees of the Ninth Guru were executed within red fort in Chandni Chowk, Delhi because they refused to give up their faith: Bhai Mati Das, “sawn alive,” Bhai Sati Das, “burnt alive,” and Bhai Dyala, “boiled to death.” On December 10, 1710, Bahadur Shah, the eighth Mughal emperor and Aurangzeb’s third son, proclaimed a Sikh genocide renforcing his father’s notion of Islam being the only pure religion.

On February 29, 1716, Banda Bahadur was captured by the Mughal army and brought to Lal Qila, Delhi, along with his wife Sushila Devi (Princess of Chamba) and their four-year-old son Ajay Singh. Sushila committed suicide when forced to separate from her son and ordered to submit to the emperor’s harem. A large number of Sikhs were captured and on their refusal to give up their faith, as many as 714 Sikhs were beheaded publicly. Their heads were arranged in pyramids at the gates of Lal Qila. On June 9, 1716, the Mughal ruler brought Banda Bahadur to the Qutub Minar area, killed his son in front of him and then executed him too. 1716, Convert or Die ordered Sikhs to convert to Islam or die. They were offered a reward for each head. Many Sikhs retreated to jungles; many embraced Hinduism; and many others gave up “the outward signs of their belief.” The Mughal government declared the Sikhs extinct.

Despite the long run struggle, the red fort was lost from mughal emperors twice during their tenure. The great Maratha King Shivaji posed the only notable resistance to Aurangzeb’s rule. The Mughal-Maratha Wars, also known as the Deccan Wars, were fought from 1680 to 1707. After Shivaji’s death, his son Sambaji also stood up bravely against the Mughals until he was captured at Sangameshwar and tortured to death. But after Aurangzeb’s death, the Marathas rose again and started their expansion toward the north. They conquered the land up to Punjab and beyond as far up as the Khyber Pass. In 1757 they hoisted their Hindu saffron flag on Lal Qila, Delhi.

In 1783, Baghel Singh, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, and Jassa Singh Ramgariah united their forces into a joint Sikh army, defeated the Mughal army, conquered Delhi, and hoisted the Sikh flag on Lal Qila constructing historical 7 Sikh gurdwaras.

1857, was the end of all Red fort’s glory from mughal chapters as Britishers formally colonized India, throwing out last emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar and his family from gates of red fort. Today, red fort is the mark of an Independent, Republic, Sovereign and a free India who formally removed all the external forces and is eligible to make its own decisions. If the walls could hear, the red walls of Lal Qila would prove to be the best storytellers of Delhi’s history; from the rise of Mughal power, the controversies with non-Muslims, the fall of great dynasties, to today’s globalization, the Red Fort is a living heritage site of Delhi which, to this day, witnesses every major and minor change in the country.

References

- Niraj kumar Singh,Sangeeta Mital.From Centre to Periphery: Changing Fortunes of the Lal Qila.

- India Habitat Center.From Centre to Periphery: Changing Fortunes of the Lal Qila.

- Dr Bikram Lamba.A Peep in History: Tale of Red Forts.

- Dr.emran jahan.Medieval Muslim Monuments in Delhi:Its history and architectural characteristic.

- Krishna Lal.Life in the Red Fort 1851-1853.

- Bikram Lamba.Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research.Lal Qila from a Sikh History Perspective and India’s Imperative to Unite the Nation.

- Colonial architecture in Delhi

- Colonial history of Delhi

- Delhi heritage tourism

- Delhi Mughal heritage

- Delhi Red Fort history

- Delhi water city tourism

- Delhi's living heritage sites

- Exploring Delhi's heritage

- Historical sites in Delhi

- Mughal period architecture Delhi

- Red Fort UNESCO site

- Sikh.

- Tourist attractions in Delhi

- UNESCO heritage sites Delhi

- Yamuna river heritage

- Yamuna river historical significance