Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Sawai Singh

One has often heard of Phoolan Devi, Pan Singh Tomar, Daaku Maan Singh, Veerappan and so forth. What comes to mind when someone says their name: dacoits, looters, criminals? In the words of scholar Eric Hobsbawm, “a bandit can be someone who belongs to the rural population or the population that is being pushed towards marginality or outlawry like soldiers, deserters and ex-servicemen.” In other words, a bandit is someone living a life based on loot, plunder, killing and attacking individually or in groups.

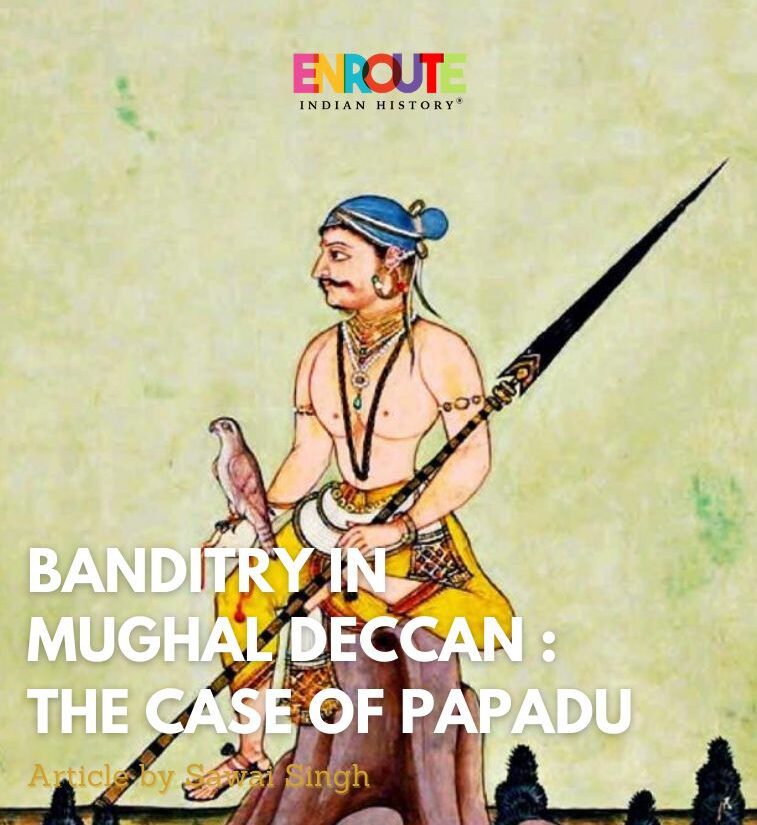

A known bandit of the past was Sarvayi Papadu, an active bandit in the first decade of the 18th century Mughal Telangana, earlier under Qutb Shahi control. An interesting fact about his story is in the official chronicle he was portrayed as a threat to the regional powers, deemed as a criminal and was executed but later he became a hero in the folk memory of people. Through his case, an attempt is made to highlight the practice within South India which made banditry not a crime but a natural caste or profession.

Before looking at the career of Papadu, it is pivotal to pay attention to the context in which he was to prosper. The area where his career would take a boom was part of the Qutb Shahi dynasty from 1518 to 1687 CE. They formulated a policy that included the patronization of the vernacular language, especially Telugu, employing the Nayaka chieftains (who held a privilege during the previous dynasty in the area) and the Brahmins in the administration giving them power into their hands. Additionally, they established the city of Hyderabad city in 1589 CE which facilitated commercial exchanges that brought prosperity to the region. The Qutb Shahi dynasty lasted till 1687 CE when the Mughals conquered the area which led to a situation of chaos and internal security hampered due to the war of succession. These conditions fostered highway robbery.

Coming back to Papadu, from the account of the Mughal historian Khafi Khan’s chronicle named Muntakhab ul-lubab. According to this version Papadu belonged to the caste of toddy-tappers. In the late 1690’s CE he assaulted and robbed the wealth of his widowed sister and marched towards Tarikonda with his followers. There he constructed a crude hill fort to conduct activities like robbery and raiding the merchants. Eventually, he was expelled from the region by the faujdar (military governor) and zamindars (Telugu landholders/chiefs) and moved to Kaulas (Fig. 1). He could not continue with his activities as he was imprisoned there but somehow gained his freedom and left for Shahpur. This area was close to his native place Tarikonda. He gathered a large following as well as built a crude hill fort over there. Intriguingly, both Hindu and Muslim women became the centre of attack this time. This news was delivered to the emperor Aurangzeb who gave a green signal to the faujdar of Kuplak, named Qasim Khan, to attack Papadu but he, unfortunately, perished in the fight.

Figure 1: Map of Eastern Deccan under Aurangzeb

In 1702 CE deputy governor Rustam Dil Khan was dispatched for the same cause. He laid siege for two months which resulted in the fleeing of Papadu and the destruction of his hill fort. But Papadu’s stubborn behaviour brought him back to Shahpur where he strengthened his base by constructing a fort with stone and mortar and outfitted it with a fixed cannon. The structure is present even to date (Fig. 2). Papadu slowly gained popularity and conquered the nearby forts. Historian Eaton argued that Papadu was on his way to becoming a regional warlord. One strong ramification of his growth was that during 1702-1704 CE not even a single trade caravan could reach Hyderabad.

FIGURE 2: Shahpur: walls and watchtower of fort, looking northeast

An engrossing event occurred in 1706 CE when Rustam Dil Khan approached Riza Khan, another bandit to suppress Papadu. If we think of it in contemporary times, it sounds like approaching Phoolan Devi to suppress Veerappan. But this attempt failed. In another interesting turn of events, when Rustam Dil went all by himself to attack Papadu, he was settled with a bribe. The power of wealth boosted Papadu’s confidence manifold times and he planned a raid in 1708 CE on Warangal (the capital of the Kakatiya dynasty and well fortified by them, the Bahmanis and Qutb Shahi) which was successful. He plundered the city continuously for two to three days. Moreover, upper-class locals, inclusive of women and children, were abducted and taken to Shahpur. It is presumed that he took people as a ransom.

One may wonder what was the reason for his hatred or attacks. The answer lies in the historical context where Brahmins and Telugu chiefs were given administrative powers allowing them to impose the varna system. This hampered the opportunity for people like Papadu to become socially mobile and follow other professions than being a toddy-tapper and hence this can be a stronger reason for his angst against both Hindus and Muslims. At the same time, the opportunities developed under the political chaos due to the Mughals compromised the internal security of the region. And to continue to be a rebel he purchased gunpowder and arms and ammunition.

His career reached a zenith in January 1709 CE when he paid a sum of rupees 1,400,000 to Bahadur Shah in a durbar held in Hyderabad and received a robe of honour (a practice where the personal garment of the emperor was given) in return. The Mughal urban nobility and Telugu aristocracy of the region felt challenged. Soon a complaint was presented to the emperor and Yusuf Khan, the governor of Hyderabad, was given the task to handle Papadu. Before the attack could commence the captives of Papadu at Shahpur were released by his wife because her brother was one of them, and they rebelled in the fort. Papadu tried hard to handle the situation and gain control of his fort but towards the end, he fled to Hasanabad. There he was recognized by a toddy tapper who handed him over to Yusuf. He was executed and his head was handed to the emperor and his body was hanged as a warning to the people.

FIGURE 3 : Portrait of Papadu by an anonymous artist (c. 1750–80). Courtesy: V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, No. IS-205-1953.

Papadu’s story from a ballad via a folk poem’s narrative point of view includes some interesting details: he belongs to a very lowly caste of toddy-tapper amongst the Hindus; the Brahmins enter into the story and predict the royal future of Papadu; Papadu pours hot oil on his mother’s body to extract her hidden wealth; he rapes a new bride when he reaches a village; the list of his followers is given where people from different sections of the society joined him like people from the caste of cotton carder, washerman, basket weaver, barber, landless peasants and so on; and towards the end, he is hit with a boy’s gunshot but before his life comes to an end his he beheaded himself.

An important insight given by historians Richards and Rao. They suggest that layers of legend and myths have been added to legitimize Papadu. One of them is the layer of Sanskritization which allowed the bandit to become a part of the larger narrative. For instance, the prediction of Papadu’s royal fate by the Brahmins occurs in the story. This to some extent goes against the angst that Papadu held for the Hindu elements of the society in the chronicle narrative. Second is how Papadu dies. In the folk version, he beheaded himself to die in the manner of a king. Hence, by “self-sacrificing” himself he becomes a hero and hence is destined to attain a royal burial. This makes it evident that in the deification process, the positive attributes are fleshed out despite the negative acts and the same happened with Papadu.

Historian Eaton has called Papadu a social bandit by using the concept of another scholar Eric Hobsbawm. Accordingly, social bandits are looked upon as criminals by the state but are seen as a leader, a hero, a liberator, and a representative of the “oppressed against the oppressor” from the societal point of view. The genesis of such bandits is possible in agrarian societies, like India, and also during grave economic crises and pauperization, which was exactly the case in Deccan with the advent of the Mughals.

Lastly, it is important to understand why such heroization was happening. An interesting practice prevalent in the South Indian myths and poems has been highlighted by the scholar David Shulman. He argues that the birth of bandits was a natural thing rather than a by-product of something. Hence, banditry took the shape of a profession or a caste. The hero worship of bandits, robbers or thieves is deeply inspired by the roles of Shiva and Vishnu who themselves committed acts like Shiva kidnapping his bride and Krishna stealing the clothes of ladies taking bath and so forth. These acts which became glorified then become necessary to be re-done to attain reverence from the people.

Thus we looked at the process of making a bandit, his enormous wealth, his attempts to become a warlord and how myths are given shape in a South Indian context that stands in contrast to the dominant narrative. This case also reflects upon the mobility and status one could attain in the 18th century based on wealth. It will be interesting to see if in the near future, we have newer myths and popular memory revolving around the dacoits who died in the 20th or 21st century.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eaton, Richard M. “Papadu: Social Banditry in Mughal Telangana,” in A Social History of The Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 129-176.

Hobsbawm, Eric J. Bandits. 3rd Ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1981.

Richards, J. F. and V. N Rao. “Banditry in Mughal India: Historical and Folk

Perceptions.” Social History Review, Vol. XVII, No. I (January 1, 1980). pp. 95-120.

Doi- https://doi.org/10.1177/001946468001700103

Shulman, David Dean. “Bandits and Other Tragic Heroes.” in The King And The Clown In South Indian Myth and Poetry. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1985, pp. 340-400.