Article by EIH Researcher and Writer

Anupam Tripathi

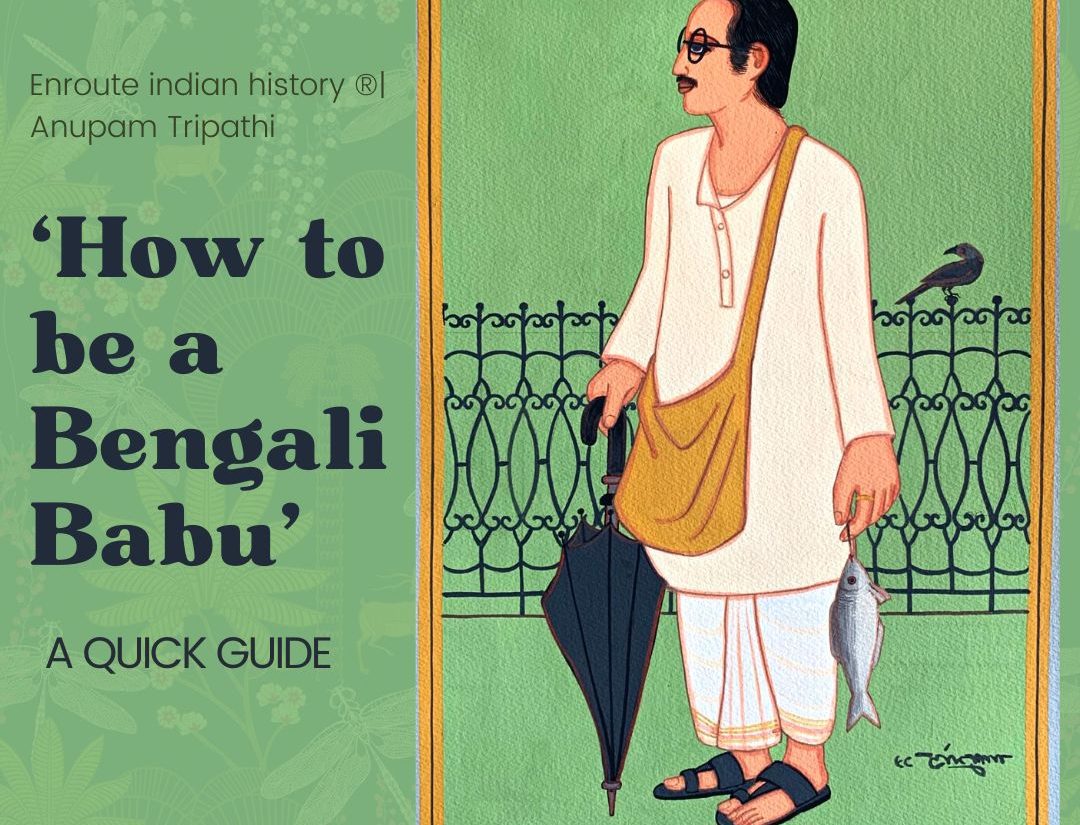

Characterized by “gentle” characteristics and Western education, the rise of Bhadralok in the 19th century reflected changes in the nature of Bengali identity and subjectivity. The colonial experience led to the concern of the Bengali elite to define for themselves a social class that would delineate their nobility and shape a new code of ‘acceptance’. The “Babu” were associated with this new class of Bengalis eager to adopt Western manners and learn that they formed the bulk of the workforce needed in the cosmopolitan enclave of Calcutta. There have been several attempts by scholars to define this very abstruse social category. Some view them as all those who are not chotolok, or the hoi polloi, while others understand them as ‘de facto social group, which held a common position along some continuum of the economy, enjoyed a style of life in common and was conscious of its existence as a class organised to further its ends’. The prototype Babu was one whose attire was a variety of English and Indian , claiming to be taught English and flaunting his status in society.

The title ‘Babu’ was added as a prefix or suffix to a person’s name to recognize (wealthy) Indians who had provided service and assistance to the British in establishing their commercial and political base in India. Raja Nabakrishna Deb of Shobhabazar Rajbari was the first known ‘Babu’ from Calcutta. A learned intellectual with a good command over Persian and Urdu, he served as a close confidant of Lord Clive. With his help, Clive gained many allies and thus established British suzerainty in Bengal. The first Durga Puja was celebrated by the Raja at his palace in North Calcutta after the British victory at the Battle of Plassey. The celebration was a great dream, embellished by the presence of many English people and the Bengali aristocracy. Thus began the trend of Durga Puja extravagance by various elites or Babus of Kolkata. Among the eminent aristocratic families of Kolkata, the most prominent were Tagore of Jorashanko, Mullicks and Deb of Shobhabazar. The rise of the Bengali Babu (or Babu) as a social class was mainly due to trade and enterprise in British colonial Bengal.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Bengali merchants formed a significant trading community in the Bengal Presidency. Not only did they play a prominent role as interpreters and intermediaries for foreign merchants, but a significant number of them also entered into commercial joint ventures with their European partners. Most of them belonged to the trading community of Bania. They became brokers and agents for foreign business ventures and served as cross-cultural collaborators. All commerce in Bengal was concentrated in the hands of a few families who, in addition to managing goods, ran banks, insurance companies, shipping companies, trading houses, flour mills and speculative markets. Babu was an honorary title bestowed on these people by the East India Company and in some cases, like Biswanath Motilal, by Queen Victoria herself. They managed all the commercial affairs of Calcutta (now Kolkata) and amassed great fortunes. They were not only active partners of Western agency houses, but sometimes even employed Europeans in their companies. Babus differed from the ‘chotolok’ in their caste, class, education and respectable status in society. As colonial officials and associates of the Raj, the Babus remained alienated from the Indian masses. They were never fully assimilated as part of the English cohort as well. Both in England and at home, the Babu were ridiculed as an absurd mixture of imperialist culture and indigenous traditions.

Post 1857, we witness a change in the way these Babus were represented in the popular domain. The young Bengali Babu was presented as a cartoon character, a ridiculous fusion of East and West, wearing a dhoti, coat and hat, wearing a monocle, carrying an umbrella and smoking a cigar. What began as a gentle mockery of the Anglo-Indian way of life soon became an exercise smack of racism and anti-India attitude. The figurative mockery of Babu’s features was often accompanied by appropriate comic verses, like:

There was a Baboo of Calcutta

Who lived upon ‘clarified butter’

Till he grew as obese

As cramm’d Strasbourg geese,

This ghee-fed Baboo of Calcutta.

Reference:

- Sutapa Dutta, Packing a Punch at the Bengali Babu.

- Swapna Banerjee, Men, Women, and Domestics: Articulating Middle-Class Identity in Colonial Bengal.

- V. Sreeja, Babu English Revisited: A Sociolinguistic Study