Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Sawai Singh Panwar

The Mughal Empire thrived from 1526 to 1857 CE and was known for its diplomacy, war techniques, usage of gunpowder, state policies, the concept of kingship and so on. The historians working on this empire were also fascinated by its art and architecture. In this essay, I intend to introduce the concept of portraiture as well as the politics surrounding it, in the period of Akbar and Jahangir. Additionally, I will also highlight the usage of Islamic, Indic and European concepts and painting techniques used to paint these Mughal portraits.

Portraiture in simpler words means that it shall focus on the individual’s or object’s physical accuracy as well as showcasing their persona and characteristics. Art historian Mika Natif highlighted that the concept of portraiture saw a semantic shift during the Mughal period as compared to the pre-modern Persian world’s concept by reading the primary sources and inscriptions on painting. Accordingly, in the Persian world, the term used for portraiture in the most generic sense was “surat” which consisted of varied meanings related to the “form” like “picture, portrait or image.” On the other hand, Mughals preferred the term “shabih” on their portrait’s inscription which emphasizes “likeness” over “form.”

A shift in the Mughal painting can be seen by comparing the paintings of the second Mughal ruler Humayun with that of his grandson Jahangir’s paintings. In Humayun’s time, the prominent features included costume, headgear, facial features and pose. But during Jahangir’s period, the weightage was given to the facial features, the use of light and shade, and the weight and volume of the body of the sitter.

What makes portraits interesting under the Mughals is the examination and comments made by the emperor on them. These comments, on the character, ability, lineage and so forth of the individual, looked as if the emperor was having a close conversation with the individual himself.

This sounds a bit crazy, doesn’t it?

Let me share with you the spiritual concept in Islam which is known as the practice of physiognomy, which is the facial feature of an individual that is indicative of his/her character or ethnic origin. According to this practice, the inner character, nature and moral comportment are being reflected by the individual’s physicality. This hints at the deeper connection of the outer appearance (surat) with the inner essence (mani). For the same reason and belief, the emperor got their portraits made and viewed them as their external appearance as well as essence, that is their self and empire.

The impact of such practice became visible since portraits were considered surrogates of the individual by the Mughals due to a strong belief that pictures contained a power of transience. To further elaborate on this when Jahangir’s army was defeated during the Deccan campaign he was so infuriated that he ordered the portraits of those officials be made who had fled during the war. Then he looked at each one of them and gave a remark. This particular incident, in Mika Natif’s opinion, shows that he used the portraits for public rebuke.

Since the portraits had spiritual as well as political characteristics, a sharp intellect and technical expertise became a prerequisite for the artist for their production. Under the Mughals, there were certain painters exclusively painted the face and hence were known as chihra nami, chihra kusha’i or chihra kar. In Figure 1, for instance, titled Akbar lost in the Desert, the artist who worked exclusively on faces was Kesu and other parts of the painting were completed by the artist Mahesh.

FIGURE 1 – Akbar Lost in the Desert While Hunting Wild Asses, by Mohesh and Kesav, folio from the Akbarnama, ca. 1586–89, Mughal India. Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper. 33.4 × 20.1 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, IS.2:84–1896.

Under Akbar as well as Jahangir, portraits were made for the practical, spiritual, diplomatic gifts and mementos. Therefore, they became a pivotal tool to gain political, cultural and socio-religious powers. This purpose was achieved by using European techniques of light and shadow, volume, depth and so forth by the Mughal artists. Let us look at two examples to corroborate these facts.

In the first case, Figures 2 & 3 are two different portraits of Ibrahim Adil Shah II, the contemporary of Jahangir and the ruler of Bijapur. Figure 2 was made by the artist Hashim under Jahangir’s commission. If we compare this with Figure 3 made in the Bijapur itself, then the paintings do not resemble each other. This becomes fascinating. But why is it so? The scholar Keelan Overton believes that the artist Hashim through this portrayal is trying to highlight the fragility and weakness of Adil Shah II, who is a rival of Jahangir. His figure reflects a state of surrender to Jahangir. Mika Natif too argues in a similar vein and opines that Adil Shah II is portrayed in a tired and submissive manner, as an old man with a grayish beard, darkish skin, with minimal jewelry and plain clothing that completely strips him of his authority as a king. Hence this portrait becomes a political statement, as a testament to Mughal hegemony in the opinion of Natif.

FIGURE 2 – Portrait of Ibrahim ʿAdil Shah II of Bijapur, by Hashim, ca. 1620, folio from the Shah Jahan Album, Mughal India. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. 38.9 × 25.4 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art 55.121.10.33.

On the other hand, the Deccan portrait reflects him as an ideal ruler with a statement of grandiose power, culture and generosity. His body appears strong and firm and his facial expressions reveal beauty and power.

FIGURE 3 – Ibrahim ʿAdil Shah II of Bijapur, ca. 1615, folio from an album, Bijapur, Deccan. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. 17.0 × 10.2 cm. British Museum 1937,0410,0.2.© The Trustees of the British Museum

The portrayal of Adil Shah II was not an exception during the Jahangiri period. Even the portraits of the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas were made with a similar political tone showing him as subservient to Jahangir.

Another political aspect was the distribution or exchange of portraits through diplomacy. In Jahangirnama, Jahangir wrote that the Golconda ruler Qutubulmulk requested his portrait once he became an ally of the Mughals. Additionally, he also gave him two jeweled daggers. The portraits from England to the Mughal court by Sir Thomas Roe are another example of diplomatic exchange.

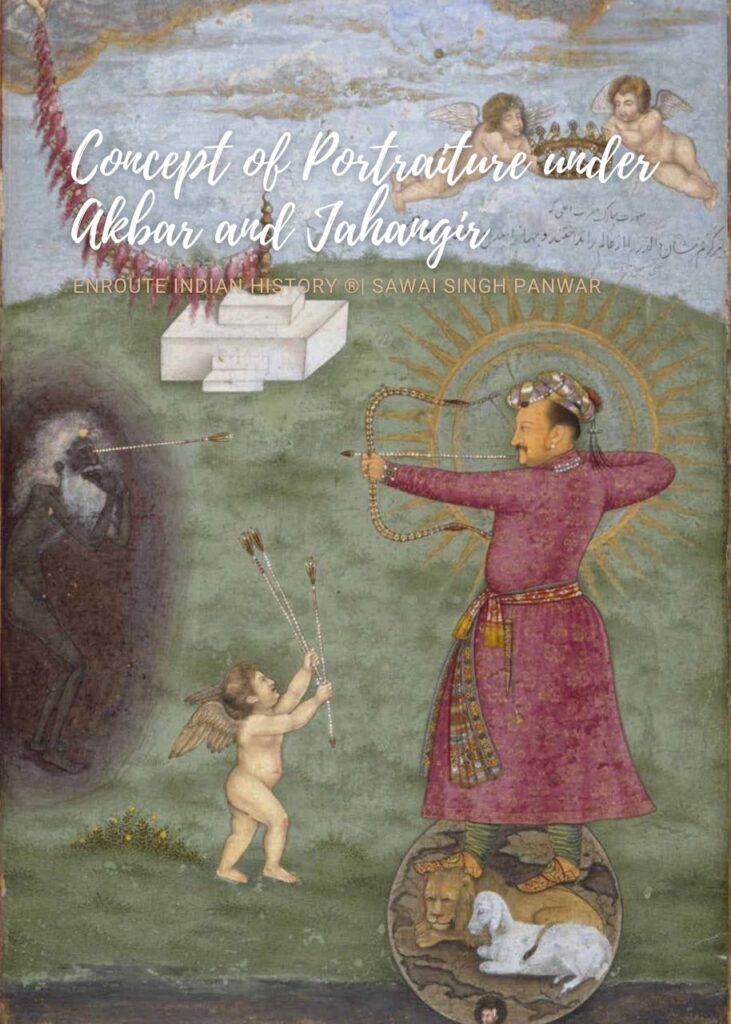

In the second example, Figure 4, the Persian script in the picture states, given by the historian Azfar Moin: “auspicious image of His Supreme Majesty (Jahangir) whose arrow of kindness destroys dalidar from this world and recreates the world anew with his justice and fairness.”

FIGURE 4 – Emperor Jahangir Triumphing over Poverty (detail from folio). Attributed to Abu’l Hasan, ca. 1620–1625. Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on page, 23.81 × 15.24 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates, purchase M.75.4.28.

This illustration is inclusive of ideas from Islamic, Indic and European concepts. Moin’s observation on this is fascinating to note.

In this painting’s script, written in Persian, the Hindi word “dalidar” is used derived from the Sanskrit word “daridra,” meaning poverty. Looking at the Hindu traditions, Daridra is the sister of Goddess Lakshmi yet is the Goddess of misfortune and poverty. This highlights a ritualistic meaning where Jahangir is making his realm free from poverty, by shooting an arrow towards the black image reflective of poverty. Another meaning of dalidar can be associated with evil, darkness and corrupt world order. Moreover, there is a conscious use of the Indic cosmological cycle. This can be seen from the symbol of a fish, which can be understood as the Matsya avatar of Vishnu. The man sitting on it is Manu who was carried by Vishnu during the flood which highlights that a new cycle of time has been inaugurated. This is directly linked with the concept of the Islamic Millennium which Jahangir was trying to portray here.

In terms of European as well as Islamic ideas, Jahangir used the Biblical concept of messianic peace employed here through the imagery of the lion and the lamb in harmony, at his feet. Art historian Ebba Koch thinks that the peaceful coming together of the hunter and the hunted, here lion and the lamb, is also a part of ancient Iranian myth. Additionally, the usage of European symbolism like the halo, puttis and the concept of a globe of the earth was also used to justify Jahangir’s (name) claims of the seizure of the world.

Overall, this shows his awareness of Jahangir of the customs, traditions and concepts of the land he ruled as well as of ideas floating within his empire due to the English companies. He carried Akbar’s legacy through the clever use of such concepts in several other paintings. Such illustrations hinted at the sacred kingship that Jahangir wanted to highlight.

Towards the end, by looking at these case studies it becomes evident that the concept of portraits that seemed simple was rather a product of a web of complex meanings that the Mughals utilized for various purposes. The conscious use of concepts existing around them shows their deliberate tapping on ideas that could fulfill their claim of being a world monarch. Thus Mughal art becomes a lens to look into the outer as well as inner meanings of the portraits that the monarchs cleverly used.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Moin, Azfar. “The Throne of Time: The Sacred Image of Jahangir.” The Millennial Sovereign: Sacred Kingship & Sainthood in Islam. Columbia University Press, 2012, pp 259-318.

Natif, Mika. “Chapter 5.” Mughal Occidentalism: Artistic Encounters between Europe and Asia at the Courts of India, 1580-1630. Brill, 2018, pp 205-261.

Verma, Som Prakash. “Portraiture.” Painting The Mughal Experience. Oxford University Press, 2005, pp 57-87.