The statue of the first king of Kirat, Yalamber, situated in Mudhe Sanischare, Sankhuwasabha, Nepal. Source: Himalayan Cultures.

In the ancient, mist-covered valleys of the Himalayas, where the whispers of nature are intertwined with the breath of the wind, lies a spiritual legacy as old as the mountains themselves—the Kirat Mundhum. Unlike written scriptures, the Mundhum is a living tradition, passed down through generations not by ink on paper, but through the voices of shamans who speak the language of the earth. It is more than just a text; it is the heartbeat of the Kirat people, a guide that unravels the mysteries of creation, the sacredness of nature, and the ancestral wisdom that binds them to the cosmos. The Mundhum is a sacred book, leading its followers through the cycles of life, death, and rebirth, while teaching them to walk in harmony with all living beings. It is in this timeless narrative that the Kirat people find their identity, their purpose, and their connection to the divine.

What exactly is Mundhum and where did it originate?

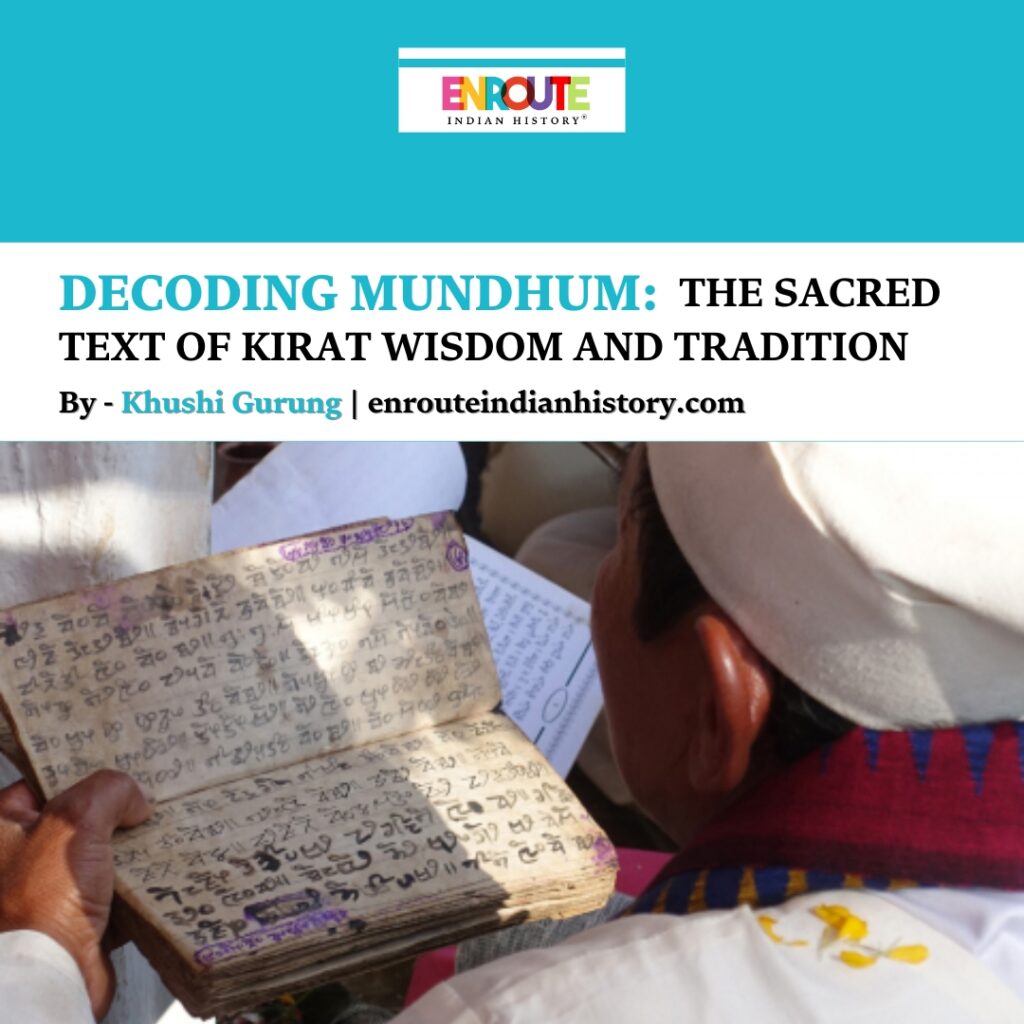

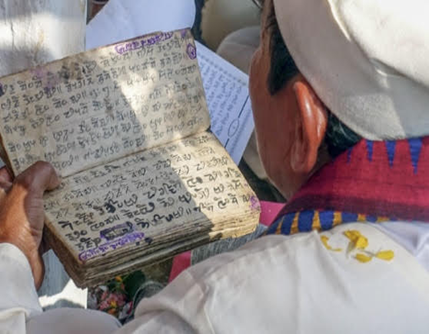

Satyahangma priest reading the Samjik Mundhum in Limbu Script, Photo by Martin Gaenszle 2018. Source: Brill.

Mundhum or Kirati Veda is the religious scripture and folk literature of the Kirat people of Nepal and India and is central to Kirat Mundhum. Mundhum means “the power of great strength” in the Kirati languages. Written in ancient Kirati language and versions among various Kirat tribes like Khambu (Rai), Limbu (Subba), Sunuwar (Mukhia) and Yakkha (Dewan), it is the ancient and sacred spiritual book of the Kirat people, an indigenous community primarily residing in the eastern Himalayan regions of Nepal, India, and Bhutan. This holy book talks about customary practices that serve as rules of law and guide Kirats in their daily life. Mundum is usually followed by Kirat societies. Kirat society existed before Vedic period in Kailash Parvat and Himalayan regions of Indian subcontinent. Unlike conventional religious scriptures, the Mundhum is not a singular written book but a vast body of oral traditions, myths, rituals, and teachings from the first Prophet Yehang to Falgunanda which have been passed down through generations by shamans and spiritual leaders within the Kirat community. Religious texts mean the power of great strength Mundhum in the Limbu language, Mewahang call it muddum, Yakka as mintum, Sunuwar as mukdum among Kulung as ridum Bantawa as Mundum and Chamling as dum. It covers many aspects of the Kirat culture, customs and traditions that existed before Vedic period in the ancient Indian subcontinent. It is a book of history, religion, and philosophy of the Kirat people and encapsulates the Kirat people’s beliefs, cosmology, and cultural practices, offering guidance on everything from the creation of the universe to social norms, ethical conduct, and the veneration of nature and ancestors.

In the Kirat Limbu Mundhum, the Mundhum is organized into two parts — Thungsap and Peysap whereas in Kirat Rai, Oral Mundum is called “Doedum” or “Doewangdum” and Written Mundum is called “Chapdayang or Chhapladum“. This suggests that the Mundhum of the Kirat community had different names depending on the specific tribe it belonged to, but the underlying information and teachings remained the same across all tribes.

The Thungsap Mundhum is the original part and was originally passed down orally until the art of writing was introduced. It was an epic recited in songs by the learned Sambas or poets. The Kirat priests in the beginning were called the Sambas where, Sam means song and, Ba means the one who (male) knows the Song or Sam. The Thungsap Mundhum is concerned with rituals, ceremonies, and the rites of passage that mark important stages in the life of a Kirat individual. This section provides detailed instructions on how to conduct rituals for birth, marriage, and death, ensuring that these significant events are performed in accordance with the sacred traditions. The Thungsap Mundhum also includes seasonal rituals and festivals, such as Chasok Tangnam and Sakela, which are celebrated to honour the spirits of nature and the ancestors. These ceremonies are deeply rooted in the agrarian lifestyle of the Kirat people, reflecting their close relationship with the land and its cycles.

Peysap Mundhum focuses on the agricultural and environmental aspects of Kirat life. It includes rituals and ceremonies designed to ensure a successful farming season, protect crops from natural disasters, and maintain a harmonious relationship with the land. There are many segments in this section of mundhum like the land ritual mentioned as Sappok Chomen, crop protection ritual mentioned as Yele Tenkoma etc This section emphasizes the sacredness of the earth and the importance of living in harmony with nature highlighting the spiritual significance of farming and the close bond between the Kirat community and the natural world. Peysap Mundhum is divided into 4 parts. They are the Soksok Mundhum, Yehang Mundhum, Samjik Mundhum and Sap Mundhum. The Soksok Mundhum contains the stories of creation of the universe, the beginning of mankind, the cause and effect of the sins, the creation of evil spirits, such as the evil spirits of Envy, Jealousy and Anger and the cause and effect of death in childhood. The Yehang Mundhum contains the story of the first leader of mankind who made laws for the sake of improvement of human beings from the stage of animal life to the enlightened life and ways to control them by giving philosophy on spiritualism. The Sapji Mundhum states the spirits are of two classes: the Good Spirit and the Bad Spirit. As the Kirat people in the beginning were rationalistic idolaters, they neither had temples, altars nor images, conceiving that none of these was necessary, but that the God resided in light and fire.

Public recitation from the Samjik Mundhum in Phidim, Nepal, Photo by Martin Gaenszle 2018. Source: Brill

According to Kirat Mundhum in the very beginning there was nothing but void. Out of his will power, God created the universe and everything in it. He created the Earth along with both living and non-living things on it. Finally, He created human beings and blessed them to grow and multiply and rule over the world. As time passed people spread far and wide. They forgot the rules and regulations

that God laid down upon them. They didn’t recognize each other. They committed incest and adultery. They fought and killed each other. They began to behave like animals. They forgot God and the word of God. They sinned against God’s will. That is when the first Prophet Yehang was born. It was him who first introduced the Kirat script and wrote down the first religious texts. Long time after him, the second Prophet Lepmuhang was born during the time of the Great Deluge. History has it that he saved all those people who believed his prophecy from the deluge in a boat. He also saved each pair of species of animals and birds from the deluge. He taught people to believe and have trust in God in whatever circumstances and make a righteous living. Long after the Great Deluge came the third Prophet Kandenhang, then came the fourth Prophet Mabohang followed by the fifth Prophet Sirijangahang who it is said to have rediscovered the Kirat script which had disappeared long time ago due to which people

were devoid of religion, knowledge, and wisdom. About two centuries later was born the

sixth Prophet Falgunanda in 1885 AD in Nepal. He had his disciples rewrite the

Mundhum in the Kirat script.

How was Mundhum passed down through generations?

“Phedangma” or Limbu shamans have been reciting “Mundhum” from the time of immemorial during the performance of rite and rituals. They are the custodians of Mundhum. These shamans are not only performers but also healers. Source: Café Kalimpong.

The oral tradition of passing down the Mundhum from generation to generation is central to the preservation of the Kirat people’s spiritual and cultural heritage. Unlike many religious texts that are written down, the Mundhum has been transmitted orally for centuries, ensuring that its teachings remain a living tradition, deeply embedded in the daily lives of the Kirat community. This method of transmission reflects the dynamic and adaptable nature of the Mundhum, allowing it to evolve while retaining its core principles.

The primary custodians of the Mundhum are the shamans—known as Phedangmas, Yebas, and Yemas—within the Kirat community. These spiritual leaders are chosen through specific rituals and believed to possess the ability to communicate with the spiritual world. They are responsible for memorizing and reciting the Mundhum during important rituals and ceremonies, acting as the bridge between the divine and the human worlds.

The process of becoming a shaman often involves rigorous training, during which the apprentice learns the complex verses and chants of the Mundhum from an elder shaman, ensuring that the knowledge is passed down accurately.

The oral transmission of the Mundhum is closely tied to the rituals and ceremonies of the Kirat people. For example, during the birth of a child, the shaman recites specific chants from the Mundhum to bless the newborn and invoke the protection of the ancestors. Similarly, during weddings, the Mundhum is recited to sanctify the union and ensure that it is in harmony with the spiritual laws. These recitations are not merely religious acts but are integral to the social and cultural fabric of the Kirat community, reinforcing their identity and connection to their ancestral roots. Kirat festivals like Chasok Tangnam and Sakela are also occasions for the oral transmission of the Mundhum. During these festivals, the shamans and elders recount the stories of the ancestors, the creation myths, and the agricultural rituals described in the Mundhum. These gatherings serve as communal learning experiences, where younger generations listen to the recitations and stories, internalizing the values and teachings of the Mundhum. For instance, during Sakela, which celebrates the harvest, the shamans lead the community in dances and chants that are directly derived from the Mundhum, celebrating the connection between the people, the land, and the spirits. Despite its resilience, the oral tradition of the Mundhum faces challenges in the modern era, particularly with the influence of formal education and organized religions. However, the Kirat community has adapted by documenting parts of the Mundhum in written form and recording the recitations, ensuring its preservation for future generations. Efforts are also being made to integrate Mundhum teachings into cultural education programs, so that young Kirat people can learn about their heritage in both traditional and modern contexts.

Early Mundhum books and publications:

The Mundhum, the body of mythological narrative and ritual practice constituting the basis of Limbu identity, was originally an oral tradition. It has

only been put into writing fairly recently. But over here we get to know that Mundhum is primarily an oral tradition rather than a conventional book. It represents the spiritual and cultural wisdom of the Kirat people, an indigenous community in the eastern Himalayan regions. As we read in the pervious paragraph, Mundhum has been passed down orally by shamans and spiritual leaders known as Phedangmas, Yebas/Yemas, and Sambas. These figures play a crucial role in preserving the teachings, rituals, and myths contained within the Mundhum, which guide the Kirat people in their daily lives and spiritual practices.

Cover of vol. 3 of the Samjik Mundhum published in 1998. Source: Brill.

According to anthropologist Martin Gaenszle, the oral nature of the Mundhum is central to its existence. It was never originally written down, which allowed it to be flexible and adaptive, with variations emerging among different Kirat subgroups such as the Limbu, Rai, Sunuwar, and Yakkha. This adaptability ensured that the Mundhum remained relevant and deeply embedded in the Kirat people’s cultural and spiritual life across generations. However, as modernization and external influences began to impact the Kirat community, there was a growing concern that the oral tradition might be lost. This led to efforts to document the Mundhum in written form, starting in the late 20th century. Scholars, researchers, and members of the Kirat community began transcribing the oral recitations of shamans and elders, thereby creating written versions of the Mundhum.

These written forms serve as a means of preserving and studying the tradition, but they cannot fully capture the dynamic and lived experience of the oral tradition. The earliest specimens we know are manuscripts in the Hodgson Collection. These manuscripts (some bound as pothīs)21 are exceptional and were apparently produced for a small elite. While most deal with history and religion, they display a marked influence of Hindu ideas. Their distribution was very limited; they were apparently kept only in

private collections. Only a few books or printed volumes in the Limbu language are documented for the pre-1990 period. These older publications, despite being in Limbu, tend to use Devanagari script. In Nepal, this was due in part to censorship, but there were also technical problems with printing the Kiranti script. Moreover, the use of Devanagari had the advantage of reaching a wider audience. Early examples of religious books in Kiranti script mentioned by Kainlaas published in Darjeeling in the 1930s are E.K. Bahadur Mereng, Tum YakthungSamlo (1931), which appears to be on ritual songs, Buddhiraj Phago and Jasman Saba, Kirat Sam Mundhum, and Tilak Singh Nugo, Kirat Mundhum (1931).

Cover of the original publication of Chemjong, 1961. Source: Brill

The most well-known, and particularly successful example of the religious genre is the book called Kirat Mundhum Kahun by Iman Singh Chemjong that delves into the traditional and spiritual practices of the Kirat community, particularly focusing on the Mundhum, today considered a classic. Its subtitle inside the book is “Veda of the Kirat,” but on the outside cover of the first edition (1961) this is given as the main title. The book includes origin myths in the Limbu language (in Devanagari script). The first part of the book deals with the creation of the universe, the origin of the first human beings, the first brother-sister incest, and the origin of envy

and anger. It then turns to an account of the beginnings of ritual practices, marriage, purification rites, household ceremonies, and so on. While this sequence follows a common pattern, Chemjong unfortunately does not explain the basis

of his selection and so the result is a somewhat incoherent concoction of various ritual genres. This book is still very popular among the Kiranti, not only because it is

the first Nepali book on the Mundhum, but also because it has long been the

only one accessible. A few years later Chemjong published a smaller volume in eastern Nepal of “teachings” from the Mundhum, titled Kirāt Mundhum Khāhun (Śikṣā).28

Again, this is a collection of ritual texts, invocations, and prayers, printed in

Devanagari script and followed by a translation in Nepali.

Conclusion

The Mundhum, the sacred text of the Kirat community, is more than just a spiritual guide; it is a living repository of the community’s history, culture, and identity. Passed down orally through generations, it reflects the Kirat people’s deep connection to nature, spirituality, and their ancestral heritage. The process of oral transmission, often facilitated by shamans has ensured that the Mundhum remains vibrant and relevant, adapting to the changing times while preserving its core values. In a rapidly modernizing world, the preservation of the Mundhum is crucial for maintaining the cultural integrity of the Kirat people. Efforts to document and study the Mundhum are essential to safeguard this ancient knowledge for future generations. As more written versions emerge, there is an opportunity to bridge the gap between tradition and modernity, allowing the Mundhum to continue to guide the Kirat people in contemporary contexts. Ultimately, the Mundhum is not just a book; it is the spiritual essence of the Kirat community, a testament to their resilience, and a beacon for their future.

Bibliography

Gaenszle Martin, “The Limbu Script and the Production of Religious Books in Nepal”, Institut für Südasien-, Tibet- und Buddhismuskunde, Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2021.

Chemjong, Iman Singh. Kirāt Mundhum (Kirāt ko ved). Champaran: Rājendra Rām,1961

Chemjong, Iman Singh. Kirāt Itihās. Darjeeling: Akhila Bharatiya Kirati (Yakthum) Chumlung Songchumbho Sabha, 1948.

Rai, Devi Shanti, Suptulung as indigenous knowledge of Kirat Rai people, Available at: file:///C:/Users/Khushi%20Gurung/Downloads/gebanath,+139-147++Suptulung+as+indigenous+knowledge+of+Kirat+Rai+people.pdf

Subba, Tanka Bahadur. Politics of Culture: A Study of Three Kirata Communities in the Eastern Himalayas. Orient Blackswan, 1999.

Subba, Tanka Bahadur. “The Importance of Mundhum in Kirat Religion.” Nepal Journal of Development and Rural Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2007, pp. 23-34.

Kirat Yakthung Chumlung (KYC). “Mundhum: The Sacred Knowledge.” Kirat Yakthung Chumlung, Available at: www.kiratyakthungchumlung.org/mundhum-sacred-knowledge.