Dialectics of Identity: The Evolution and Conflict between Hindi and Urdu in Colonial India

- EIH User

- August 16, 2024

While addressing a mushaira, poet and Bollywood lyricist Javed Akhtar defined the relationship between Hindi and Urdu as “ What is the grammar of Urdu? It is the same as that of Hindi. Then, what is the grammar of Hindi? It is the same as Urdu. No two languages exist apart from Urdu and Hindi that possess the same grammar.” Then how did these two languages, sharing their origins in the syncretic and pluralistic cultures of India, North India in particular, come to be witness to a plethora of debates and contestations during colonial India? 19th century India turned out to be a period when rigid boundaries were being created between both languages based on the religious and cultural identities of the speakers that led to the creation of distinct linguistic identities which eventually gave birth to communal strife that was to follow in the later decades.

Historically, Hindi, Urdu, Hindavi or Hindustani were not distinct languages and the term was often used interchangeably. Neither were they used to produce literary works. In the early sultanate period, apart from Persian, Awadhi and Brijbhasha were regarded as languages of literature. The syntax and grammar of Hindavi were taken from ‘khari boli’, the language spoken around the Delhi region. Later, an 11th-century poet, Masud Saad Salman, was known to have his diwan in three languages, i.e., Arabic, Persian, and Hindavi. One of the most famous poets of the language was Amir Khusrow, who had an extensive body of work comprising both prose and poetry and combining elements of both Persian and khari boli. He did write some verses in Hindavi, but they were not substantial enough to comprise a diwan. Thus, Hindavi could not find patronage among the royal or regional courts and travelled to central, southern and western India through the Hindu saints and Sufi poets. On its journey, it assimilated regional and local influences that transpired as Goojri in Gujarat and Dakhani in the Deccan. These languages flourished as vernaculars in their region, having a shared linguistic identity with the language in and around the royal court at Delhi. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi highlights that the name Urdu took over with poet Musahafi’s first diwan in 1780, and the term for the language was officially cemented with ‘zaban-e-Urdu-e-mualla-e-Shahjahanabad’ (the language of the exalted city of Shahjahanabad). It officially became the court language of the Mughals under the reign of Muhammad Shah II in the 18th century, who spoke as well as wrote in Hindi.

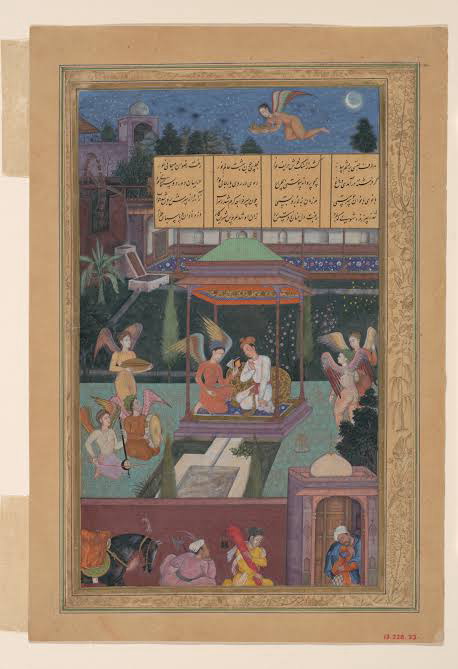

(Amir Khusrow Dehalvi was one of the most prolific Hindavi poets; Painting by Manohar; Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The first instances and a sort of foreshadowing of the Hindi-Urdu conflict that was to emerge began with the British quest for the inscription of Hindustani under the supervision of a Scottish professor of Hindustani at the College of Fort William, Calcutta, John Gilchrist. He appointed munshis to create textbooks for the education of the British recruits of the East India Company. These included prose works in two distinct languages, Hindi and Hindustani. Gilchrist considered Hindi to have originated from Sanskrit and Prakrit traditions and, hence, ought to have more Sanskritized vocabulary rooted in Indic traditions, while Hindustani was seen to have developed from an Indo-Persian culture and relied heavily on Arabic and Persian vocabulary. Both the vernaculars, of course, had different scripts which visually separated their linguistic identities. Hindi was written from left to right with more block letters in Devnagari, while Hindustani was written in the Nastaliq script from right to left with cursive letters.

(Fort William College in Calcutta was the centre of Oriental Studies; Source: Puronokolkata)

Among the masses, this distinction did not hold any relevance, especially not in any communal context. Christopher King mentions that in 1847, the principal of the English Department of Benaras College took it upon himself to improve the level of Hindi written by the students of the Sanskrit Department. When his efforts did not yield the desired results, he asked the students to write an essay on why they despised the language their mothers and sisters understood. A student replied that he and his classmates did not understand what he meant by Hindi as there were numerous dialects equally worthy of the title. It did not have any defined structure and what the professor called Hindi would merge into Urdu, and neither he nor his colleagues saw any reason to be concerned about this.

Till the revolt of 1857, the colonial regime did not indulge in any kind of controversy that could have arisen regarding the vernaculars. James Thomson, the lieutenant governor of the North Western Province between 1843 and 1853, had given equal status to Hindi as a medium of instruction in schools. But in 1848, in Delhi College, the government removed Hindi as a language of instruction as it was neither used in courts nor government colleges. Similary, in 1844 the Delhi Vernacular Translation Society was established but it primarily focused on preparing Urdu translations of English works, again disregarding Hindi. After 1857, British efforts succeeded in creating a gulf between both languages when M. S. Howel, the officiating Inspector of the first circle of the North Western Province, found Urdu to be more extensive than Urdu and proposed it as the sole language of vernacular education. Later in 1872, Devnagari script was proposed for the issuance of notifications in the civil courts in Central Province. In 1873-74, the Report of the Education Survey of N. W. P. Labelled Urdu as the language of the minority and favoured Devnagari. Similar situations arose in Bihar and Punjab. The linguistic identities were paving the way for separate communal identities.

The Hunter Commission in 1882 added fuel to the Hindi-Urdu Conflict by regarding Hindi as the most extensively used language. It was later added to the curriculum of the entrance exam of Allahabad University while Urdu was removed. This scheme was reversed in 1891 when Hindi was removed, and Urdu was retained in the Pleader’s entrance exam to the Allahabad High Court.

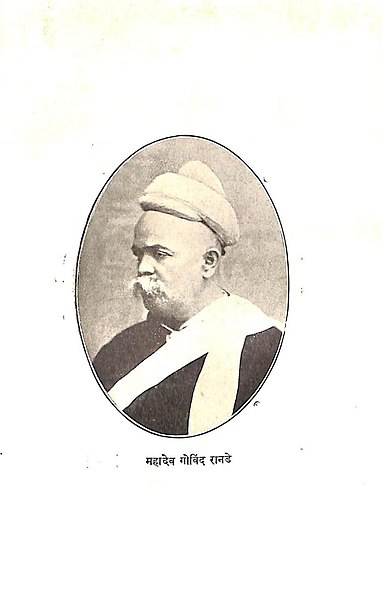

Organisations like the Arya Samaj wholeheartedly supported Hindi as the national language, while leaders like M. G. Ranade and Bal Gangadhar Tilak wanted to develop Devnagari as the common script of the country. The Hindi movement also found support in the Indian National Congress and its leaders like Madan Mohan Malviya who advocated for the introduction of Devnagari in civil and criminal courts. Another concern of the proponents of Hindi was the advantage that the Urdu speakers had, particularly those belonging to the Muslim and Kayastha communities, in government examinations.

(Justice M. G. Ranade was one of the proponents of Devnagari as the common script of the country; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Eventually, the Hindi Resolution was passed on 18th April 1900, which introduced Devnagari characters in courts and revenue offices and made the knowledge of both Devnagari and Persian scripts essential to any ministerial job in colonial India. This resolution was also welcomed by Lord Curzon, the Governor-General of India, who ignored any protest that Muslims had regarding it. Curzon’s romance with Devnagari would be short-lived as he would eventually change his position and go on to appease the Muslims with the partition of Bengal in 1905.

Thus, the colonial government left no stone unturned to create a linguistic divide with explicit communal connotations in a shared cultural heritage that had existed in the subcontinent for centuries. To counter this narrative, the National Movement led by the Congress proposed the idea of Hindustani as the national language of India to forge a common link between the Hindus and Muslims. Regarding Hindustani, Gandhi wrote, “I have come to the deliberate conclusion that no language, except Hindustani—a resultant of Hindi and Urdu—can possibly become a national medium for the exchange of ideas.” Nehru also accepted the Gandhian belief of Hindustani as the lingua franca of the nation not only due to its secular tendencies but also because historically, Urdu was regarded as the language of the sophisticated urban populace, while Hindi was seen as its rustic other. He saw Hindustani as the bridge between the rural and urban.

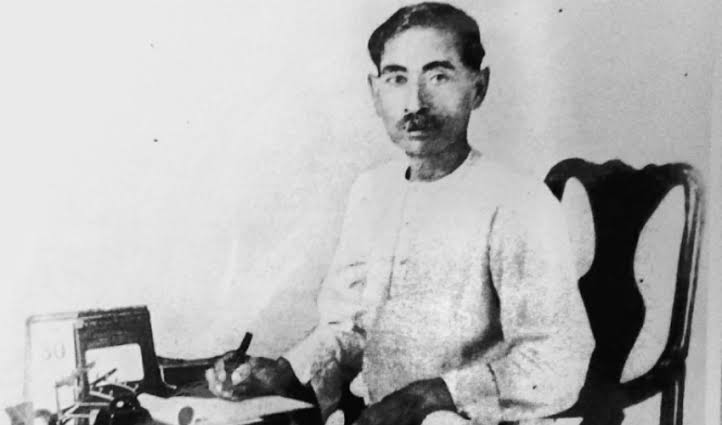

The anti-colonial movement also witnessed authors and poets vouching for Hindustani as the national language. The Progressive Writers’ Association came up with a creative solution with a Hindustani language that will have a yet-to-be-imagined Indi-Roman script, that could not come to fruition. One of the most prolific Hindi novelists, Munshi Premchand, in his essay ‘ Urdu, Hindi aur Hindustani’ wrote, “Our national language can only be that whose basis is universal intelligibility. A one that everyone can comprehend easily. Why should it concern itself with the fact that a certain word ought to be dropped because it either belongs to Persian, Arabic or Sanskrit?…if a word or an idiom or terminology is prevalent among the common public, then it does not concern itself with the origin of that word. And that (language) is Hindustani.”

(Munshi Premchand; Source: Indian History Collective)

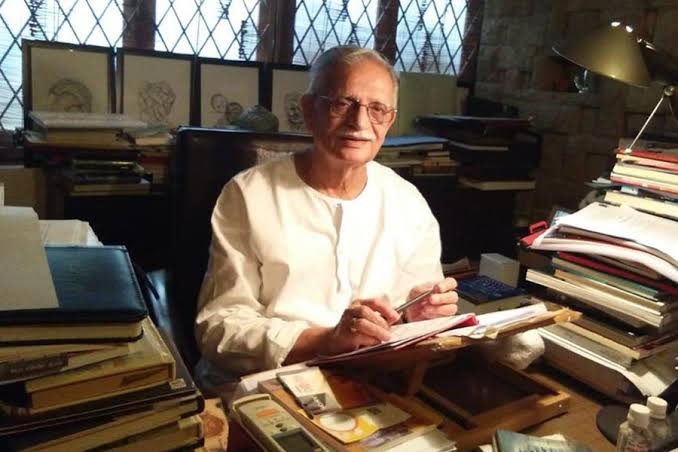

Hence, the trajectory followed by Hindi and Urdu in Colonial India from coming from a shared cultural heritage to being almost antagonistic due to colonial policies and claiming their origins to religious traditions rather than cultural identities played a significant role in providing justifications for the Partition of India. The idea that Hinduism and Islam could not coexist not only because of communal differences but also because of different cultural and linguistic identities was widely approved by the proponents of partition who found their arguments being echoed in the works of the early orientalists like William Jones and Charles Wilkins. Congress’ proposal of Hindustani as a unifying language lost its currency in the post-independence period. Nonetheless, a vast majority of north Indians today majorly speak Hindustani, an amalgamation of both Hindu and Urdu, though they tend to only identify with either of them. Moreover, the legacy of this linguistic tradition is still carried forward by the Hindi film industry, which continues to produce films and songs having elements of both Hindi and Urdu, or Hindustani.

(Bollywood filmmaker and lyricist, Gulzar is among the many writers in Bollywood who write their songs and screenplays in Hindustani; Source: The Telegraph)

References:

- Lahiri, Madhumita. “An Idiom for India.” Interventions, vol. 18, no, 1, 2016, pp. 60-85.

- Mufti, Aamir R. “Orientalism and the language of Hindustan.” Critical Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 3, 2010, pp. 63-68.

- Farooqi, Mehr Afshan. “The ‘Hindi’ of the ‘Urdu.’” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 9, 2008, pp. 18–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40277198. Accessed 11 Aug. 2024.

- Jaswal, G. M. “HINDI RESOLUTION: A REFLECTION OF THE BRITISH POLICY OF DIVIDE AND RULE.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 66, 2005, pp. 1140–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44145926. Accessed 11 Aug. 2024.

- King, Christopher. “THE HINDI-URDU CONTROVERSY OF THE NORTH-WESTERN PROVINCES AND OUDH AND COMMUNAL CONSCIOUSNESS.” Journal of South Asian Literature, vol. 13, no. 1/4, 1977, pp. 111–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40873494. Accessed 11 Aug. 2024.

- Premchand, Munshi. Urdu, Hindu aur Hindustani. 1934, https://franpritchett.com/01glossaries/pritchett/premchand_u_h_hindustani_HINDI.pdf (translation is my own)

- Sengupta, Papia. “Hindi Imposition: Examining Gandhi’s views on Common Language for India.” Engage, vol. 54, no. 44, 2019, https://www.epw.in/engage/article/hindi-imposition-examining-gandhis-views-on-common-language

- Akhtar, Javed. “Urdu ki Zindagi par koi Shak nahi kar sakta.” Jashn-e-Rekhta, Youtube, 2022, https://youtu.be/4h5C857U0C0?si=SZWJkIqfflgBJ-Yp

- Colonial India language evolution

- Conflict between Hindi and Urdu languages

- Cultural identity and Hindi-Urdu conflict

- Evolution of Hindi and Urdu in Colonial India

- Hindi and Urdu in colonial India

- Hindi-Urdu language debate history

- Hindi-Urdu linguistic identity

- Historical language debate Hindi Urdu

- Impact of colonialism on Hindi and Urdu

- Language politics Hindi and Urdu