Footprints Along the Narmada: Prehistoric Animals and Forgotten Fauna

- enrouteI

- July 27, 2023

Do you know that Narmada is the oldest river in the world due to its flow through the mountainous parts of the Gondwana Plate? Today, the river Narmada is regarded as one of the holy rivers of the Indian subcontinent. Every day, thousands flock to the ghats of the Narmada to view the sahasradhara of the river, or to take a holy dip in its waters. The Narmada Parikrama, a traditional pilgrimage of circumambulating the river, is also a common practice among devotees.

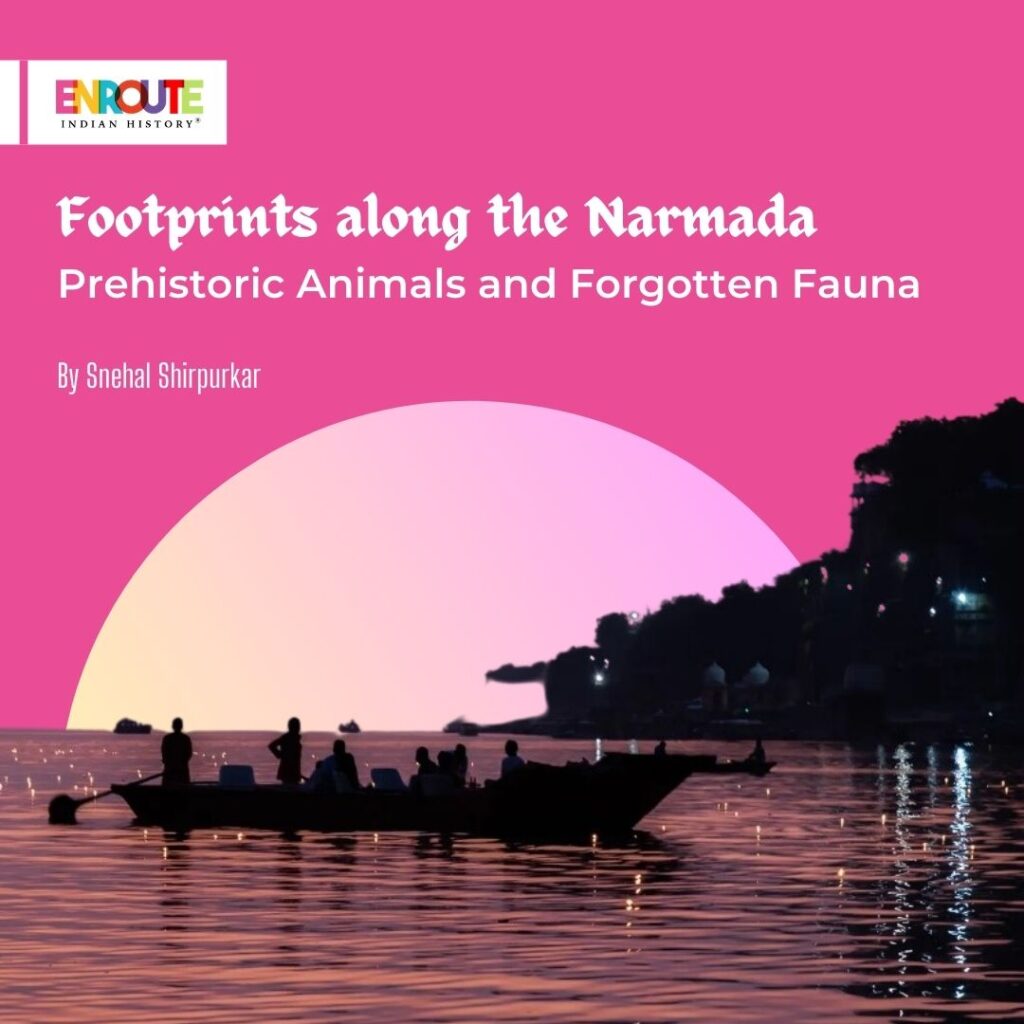

Figure 1 Boating in the Narmada. Source: Conde Nast Traveller

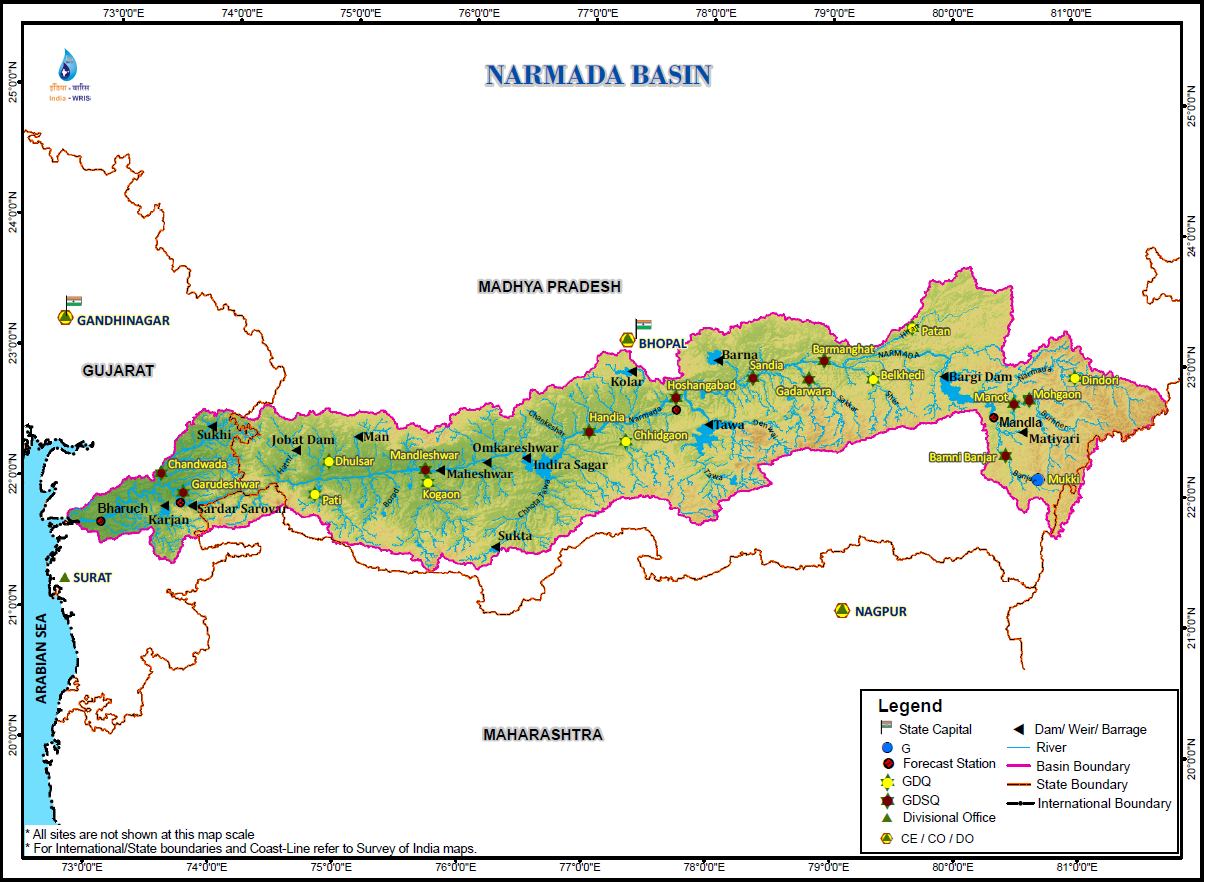

As it turns out, this river has sustained human and animal life alike, since prehistory. The Ñamadas of Ptolemy or the Nammadios of the Periplus flows across the middle of the Indian subcontinent, forming the traditional dividing line between the North and the South. Originating in Amarkantak in eastern Madhya Pradesh, it joins the Gulf of Cambay in the Arabian Sea near Broach in Gujarat. It is also known as ‘Maikala Kanya’, or ‘daughter of Maikala’ due to its origin in the Maikala hills in eastern MP, and ‘rewa’ (originating from Sanskrit root ray, or to ‘hop’) due to its leaping nature. The basin covers large areas in the states of Madhya Pradesh (86%), Gujarat (14%) and a comparatively smaller area (2%) in Maharashtra. The river is fed by several major tributaries from the southern flank, the most important being the Sher, Shakkar, Dudhi and Tawa. Tributaries like the Hiran and Sindhar join the Narmada from the northern side.

Figure 2 The Narmada Basin. Image Source: Central Water Commission

The Narmada has served as a source of sustenance since prehistoric times. The most famous evidence for this is possibly the fossilised human cranium of archaic homo sapiens discovered at Hathnora in Madhya Pradesh by Arun Sonakia in 1982. Although less famously, Narmada also served as a safe haven for animals of Prehistoric India. Where did these animals come from? What do we know of them, and why did they choose the Narmada as their dwelling place?

Faunal Footprints along the Narmada: Why are they there, and who discovered them?

Prehistoric mammalian fossils and stone tools have been unearthed from around the banks of the Narmada from different historical periods. These include the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic. This indicates that this region has offered a suitable environment for human and animal settlements throughout the Quaternary period.

The Narmada River seems to have served as a safe haven for endangered animals from other parts of the subcontinent. The Narmada Basin became the destination for these animal migrations by virtue of its strategic geographic location. The region was characterised by a warm, humid climate during the late-middle Pleistocene. It facilitated the migration of animal populations on both the North-to-South and East-to-West routes. Most animal fossils obtained appear to be survivors from the Shivalik ranges in the Himalayas. The weather conditions in the Northwest became unfavourable due to increasing aridity. An arid climate is characterised by low precipitation, high evaporation rates, and limited water availability, often causing food scarcity and dehydration risks for animals.

After such migrations, evidence suggests that the early forms of Pleistocene fauna eventually perished due to the ecological stresses. These include adverse climatic factors and other reasons, such as non-adaptability, evolutionary pressures, population pressures, and gradual climatic changes. However, some species did evolve into more advanced forms, going through a few generations, and eventually manifesting in wild and domesticated forms. Examples of these evolved species include various elephants, pigs, cattle, buffalo, rhinoceros, and some deer species, as well as carnivores, among others. Interestingly, certain animals like blackbuck, deer, chital, nilgai, etc., have maintained their characteristics from the Late Pleistocene to the present without undergoing significant micromorphological changes. On the other hand, animals like buffalo, cattle, elephants, pigs, etc., do show minor micromorphological changes in their osteology and general morphology. Some of the fauna, during the later part of the Quaternary, indicate endemic species that evolved and diversified within the Indian subcontinent.

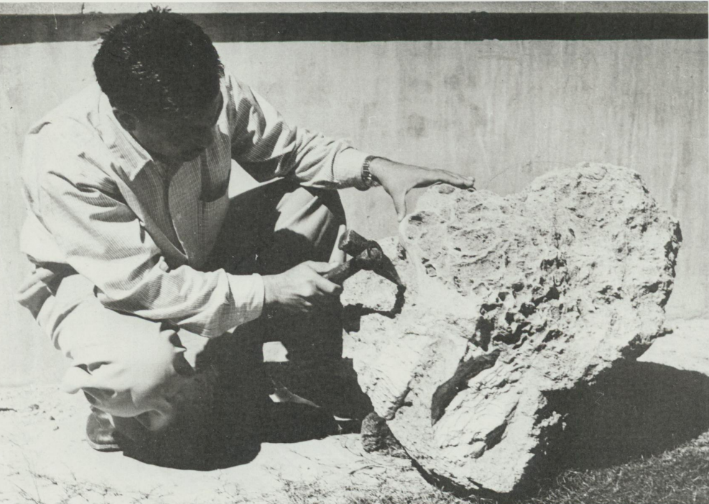

The first discovery of mammalian fossils in the Narmada Valley was made by Major General William Henry Sleeman, a British soldier and administrator, best known for the suppression of “thugees” or organised gangs of robbers and murderers between 1830 and 1856. He reported the discovery to Dr. G.G. Spilsbury of the Bengal Medical Establishment. Spilsbury later conveyed the news to James Prinsep, the Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, who published it. James Prinsep is most famous for deciphering the Ashokan Brahmi script. His contribution to uncovering the prehistory of the Narmada Valley is little known.It is curious and fascinating to note that the people involved in these discoveries are famous for something completely different, perhaps a comment on the state of prehistory and environmental history even amongst historians and subject enthusiasts. These earliest of the mammalian fossils can be compared with those from the Boulder Conglomerate Zone of the Shivalik foothills of the Himalayas. Since these early discoveries, several other archaeological finds have been unearthed in recent decades. These include reptiles such as crocodiles, the gharial, the softshell turtle. Other finds have been tusks, teeth, and skulls of elephants; the skulls, molars, and canines of hippopotamus, teeth and bone fragments of wild horses, molars of wild boars, and horns of deers. Noteworthy localities for these findings lie in the present day district of Hoshangabad. In a recent study, Jangra & Singh (2023) analyse faunal records of the central Narmada Valley to explore the possible associative evidence of prehistoric human–animal interactions.

Figure 3 In-situ elephant skull found in Ajhera, Hoshangabad district. Source: Khatri (1966)

This glimpse into the thriving animal settlements at the Narmada thus makes it unsurprising that the teak forests around the river still teem with wildlife, including ancient species. Animals of the Cervus family (a genus of deer), still found around the Narmada, are those whose fossils have also been found in the Sivalik foothills of the Himalayas. Moving forward many centuries to the 16th century, the Mughal Emperor Akbar hunted Elephants from the jungles of central India. The great Indian bison, who finds representation in the fossil record of the Narmada beds, also roams the jungles of central India. The prominence of the site, the wealth of Pleistocene mammalian fossils, and Pleistocene stone tools have made the Narmada the focus of attention of archaeologists, geologists, prehistorians, and anthropologists. However, the construction of dams along the river in contemporary times, threatens the area with the possibility of submergence of the region, and poses a grave peril to this prehistoric heritage of the country. Major dams such as the Sardar Sarovar project have been built on the Narmada River, leading to riverine damage, loss of livelihoods, and displacement of local communities. Prehistoric deposits are also threatened by the dam construction, highlighting an urgent need to accelerate research. Many fish species have already been wiped out. This time, the animals will have nowhere to migrate to.

Bibliography

Badam, G.L. “Sectional President’s Address: EVOLUTION OF ANIMALS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR UNDERSTANDING HUMAN HISTORY IN INDIA.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 75 (2014): 1046–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44158490.

Bain, Worrel Kumar. “A preliminary study on the Stone age artifacts of NetanKhedi, Sehore district of Central Narmada valley in Madhya Pradesh.” Human Kind 11 (2015): 31-49.

KHATRI, A. P. “The Pleistocene Mammalian Fossils of the Narmada River Valley and Their Horizons.” Asian Perspectives 9 (1966): 113–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42928963.

Mongabay. “Dammed and mined, Narmada River can no longer support her people”. (2019). https://india.mongabay.com/2019/09/dammed-and-mined-narmada-river-can-no-longer-support-her-people/

Patnaik, Rajeev, Parth R. Chauhan, M. R. Rao, B. A. B. Blackwell, A. R. Skinner, Ashok Sahni, M. S. Chauhan, and H. S. Khan. “New geochronological, paleoclimatological, and archaeological data from the Narmada Valley hominin locality, central India.” Journal of Human Evolution 56, no. 2 (2009): 114-133.