“From royal courts to forgotten weaves” The story of Dhaka Muslin

- enrouteI

- January 30, 2025

From royal courts to forgotten weaves : The story of Dhaka Muslin

Article By – Muskan malik

Abstract

Dhaka muslin, often described as “woven air,” was one of the most remarkable fabrics in human history, celebrated for its unmatched fineness, transparency, and elegance. In the history of textiles, there is no name more famous than that of Dhaka muslin. In Abul Fazl, the chronicler of Emperor Akbar’s court, famously wrote that muslins of Bengal were “so delicately woven that they pass through a ring,” encapsulating its almost magical quality. ¹ This legendary fabric was not just a textile but a cultural phenomenon, cherished by Mughal royalty and European aristocrats alike.

This article delves into the rise and fall of Dhaka muslin, focusing on its significance during the Mughal era, its global allure, and the ongoing efforts to revive this exquisite tradition.

The Craftsmanship of Dhaka Muslin

The delicacy of muslin cloth; Dhaka muslin came in thread counts up to 1,200, but the highest achieved in recent years is 300

Source : www.southasianjournal.net

The extraordinary nature of Dhaka muslin stemmed from the phuti karpas cotton plant, which grew exclusively in the fertile plains of the Meghna River. This plant produced fibers so fine that they had to be spun during the early morning dew to prevent the delicate threads from snapping.². It is said that the finest muslin could only be woven by master artisans whose skills were honed over generations.

These artisans, known as tantis, wove muslin so thin and light that it was often described as resembling “clouds resting on the skin.” European travelers recounted that Mughal courtiers reprimanded female attendants for appearing unclothed, only to discover they were draped in several layers of muslin!³ The fabric’s transparency and ethereal beauty were unparalleled.

Colin Thubron in his book had noted, “An Arab merchant in the ninth century was astonished to observe the mole on an imperial eunuch’s chest through five layers of gossamer silk.” The name of this Arab merchant was Suleiman. He wrote in his book, Silsiltu-T Tawarikh, about the (Dhaka) muslin, not about silk, that, “There is a stuff made in his country which is not to be found elsewhere; so fine and delicate is this material that a dress made of it may be passed through a signet-ring. It is made of cotton, and we have seen a piece of it.” 11.

Varieties of muslin were given poetic names like abrawan (“running water”) and baft-hawa (“woven air”), further underscoring their otherworldly qualities. Entire garments made of muslin were known to pass through a ring, a feat repeatedly documented by historians and travelers. ⁴

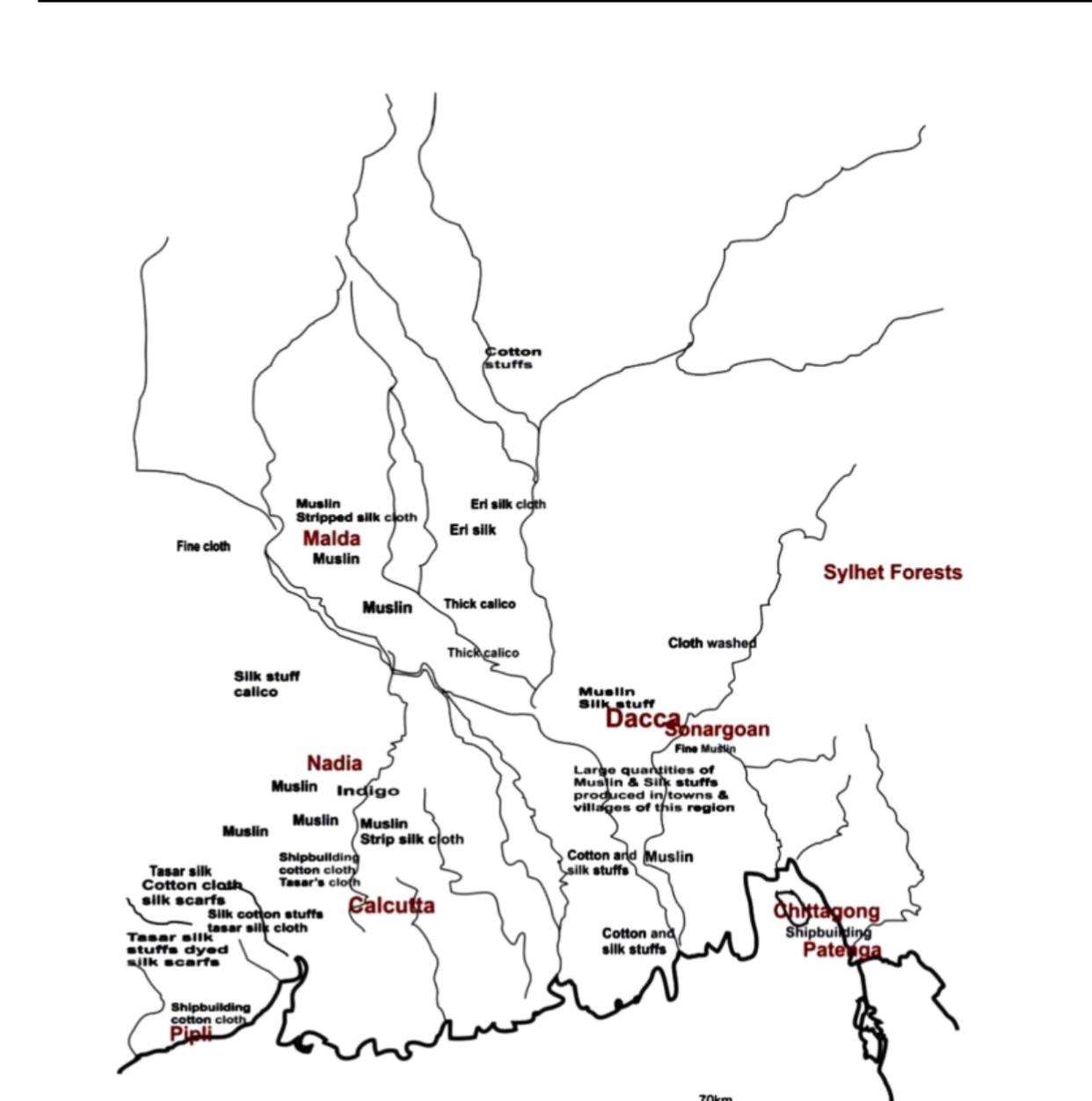

Textile map of Bengal in late 17th century

Muslin in the Mughal Court

Under the Mughal emperors, muslin reached unparalleled heights of prestige, symbolizing not just luxury but also the cultural and imperial magnificence of the Mughal court. This fine, lightweight fabric became synonymous with refinement, worn exclusively by the nobility and often reserved for the imperial family. Emperor Akbar, in his famous administrative text *Ain-I-Akbari*, meticulously categorized various grades of muslin, with the finest, *malmal khassa*, designated solely for royal us 5 Its texture was so delicate that it was often described as softer than a cloud, and its fine weave made it incredibly breathable, offering relief from the oppressive heat of India’s summers.

The fabric was more than just a piece of clothing—it was an essential aspect of Mughal court culture. Muslin was woven with a subtle elegance that allowed it to “dance with the slightest breeze,” as Jahangir, Akbar’s successor, poetically described. This lightweight quality made it ideal for the Mughal aristocracy, who would don muslin garments to stay cool in the sweltering summer months. The fabric was often adorned with elaborate gold and silver threads, transforming what was already a symbol of wealth into a truly luxurious garment. These ornate decorations reflected the grandeur of the Mughal Empire, where fashion was not only about beauty but also about demonstrating power and prestige.

What makes muslin even more fascinating is its ceremonial use, particularly within religious and diplomatic contexts. Muslin was used to wrap precious imperial gifts and sacred relics, symbolizing purity, sanctity, and the exalted status of the emperor. This practice elevated the fabric to a near-sacred level, associating it with significant cultural rituals. The delicacy of muslin, combined with its association with grandeur, made it a perfect material to honor the divine and the diplomatic, further deepening its cultural significance. It became a symbol of refinement, sophistication, and the imperial ethos of the Mughal dynasty.

A particularly mesmerizing aspect of muslin was its role in royal attire, especially the veils worn by Mughal noblewomen. These veils were so sheer that they created an almost magical effect, making the wearer seem to vanish behind the fine fabric. The transparency of the muslin veils created an optical illusion so striking that visitors would often mistake the noblewomen for being uncovered, adding to the mysterious allure of the fabric. This visual effect, combined with the luxurious lightness of muslin, only deepened its association with elegance, grace, and the supernatural.

Muslin’s integration into Mughal ceremonial practices went beyond the realm of clothing. Its use to wrap sacred objects and gifts not only highlighted the fabric’s material value but also imbued it with deeper meaning. The fine texture and its association with royalty and purity elevated it to a symbol of the Mughal Empire’s cultural and religious identity. It was not just a garment; it was a statement, an object that carried with it both tangible and intangible qualities of beauty, prestige, and power.

The enduring fascination with muslin, particularly its seamless blend of beauty, luxury, and cultural significance, made it one of the most revered textiles in history. For the Mughal Empire, it was more than a fabric—it was an emblem of the dynasty’s grandeur and its deep connection to both the everyday lives of its elite and the sacred practices that bound the empire together.

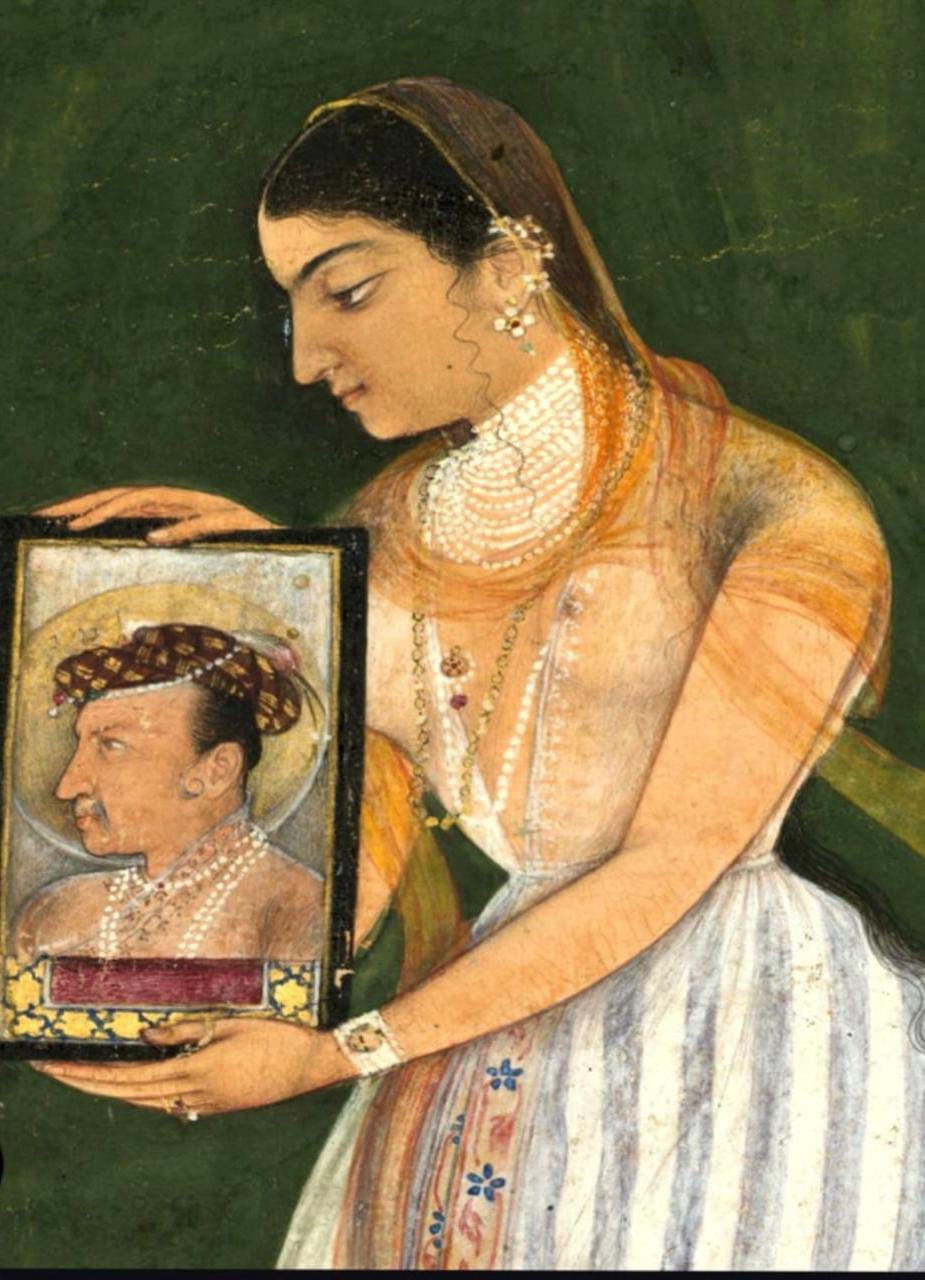

Noorajhan holding portrait of emperor Jahangir wearing makhmal

Source : www.bbc.in

A women wearing muslin

Source: Yale center for British art

Dhaka Muslin and European Aristocracy

The fame of Dhaka muslin spread far beyond the subcontinent, capturing the imagination of European aristocracy during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Portuguese were among the first to introduce the fabric to Europe, followed by the British East India Company, which turned it into a lucrative export.

Queen Marie Antoinette of France adored muslin gowns for their ethereal elegance. French nobility often wore dresses so light and transparent that they appeared to float. ⁷ in Britain, muslin became a symbol of sophistication, with women showcasing its transparency during outdoor events. The phrase “muslin fever” was coined to describe the pneumonia outbreaks that followed these displays, as women braved cold weather in their thin muslin dresses. ⁸

European poets and writers often likened Dhaka muslin to divine beauty. Some described it as “threads of moonlight,” while others compared its texture to the gentle touch of a cloud. Such descriptions reflected the fabric’s almost mythical status in European high society.

Dhaka muslin was favorite of Josephine Bonaparte, the first wife of napoleon, who owned several dresses inspired by the classical era

Source: www.alamy.com

Muslin gowns of European aristocracy

A muslin wedding gown having European motifs

Source: www.bbc.in

Different types of Muslin

The productions of Dhaka weavers consisted of fabrics of varying quality, ranging from the finest texture used by the highly aristocratic people, the emperor, viziers, nabobs and so on, down to the coarse thick wrapper used by the poor people. Muslins were designated by names denoting either fineness or transparency of texture, or the place of manufacture or the uses to which they were applied as articles of dress. Names thus derived were- Malmal The finest sort of Muslin was called Malmal, sometimes mentioned as Malmal Shahi or Malmal Khas by foreign travelers. It was costly, and the weavers spent a long time, sometimes six months, to make a piece of this sort. It was used by emperors, nawabs etc. Muslins procured for emperors were called Malbus Khas and those procured for nawabs were called Sarkar-i-Ala. The Mughal government appointed an officer, Darogah or Darogah-i-Malbus Khas to supervise the manufacture of Muslins meant for the emperor or a nawab. The Malmal was also procured for the diwan and other high officers and for JAGAT SHETH, the great banker. Muslins other than Malmal (or Malbus Khas and Sarkar-i-Ali) were exported by the traders, or some portion was used locally.

“Jhuna‟ was used by native dancers,” Rang‟ was very transparent and net-like texture, “Abirawan‟ was fancifully compared with water,” Khassa‟ was special quality, fine of elegance. “Shabnam‟ was as morning dew.” Alaballee‟ was very fine,” Tanzib‟ was as the adorning the body,” Nayansukh‟ was as pleasing to the eye,” Buddankhas‟ was a special sort of cloth, “Seerbund‟ used for turbans,” Kumees‟ used for making shirts, “Doored‟ was striped, Charkona‟ was cheered cloth, “Jamdanee‟ was figured cloth.

The Tragic Decline of Dhaka Muslin

Despite its global acclaim, Dhaka muslin faced a tragic decline with the advent of colonial rule and industrialization. The British East India Company imposed crippling taxes on Bengal’s weavers, forcing many into poverties. ⁹ The once-thriving weaving communities, celebrated for their unparalleled skill, were systematically dismantled.

Industrialization in Britain dealt the final blow. Mechanized textile mills in Manchester began producing cheaper, machine-made fabrics that flooded global markets, pushing handwoven muslin into obsolescence. Some historical accounts even suggest that British officials ordered the thumbs of master weavers to be cut off to eliminate competition, though this claim remains a subject of debate. ¹⁰

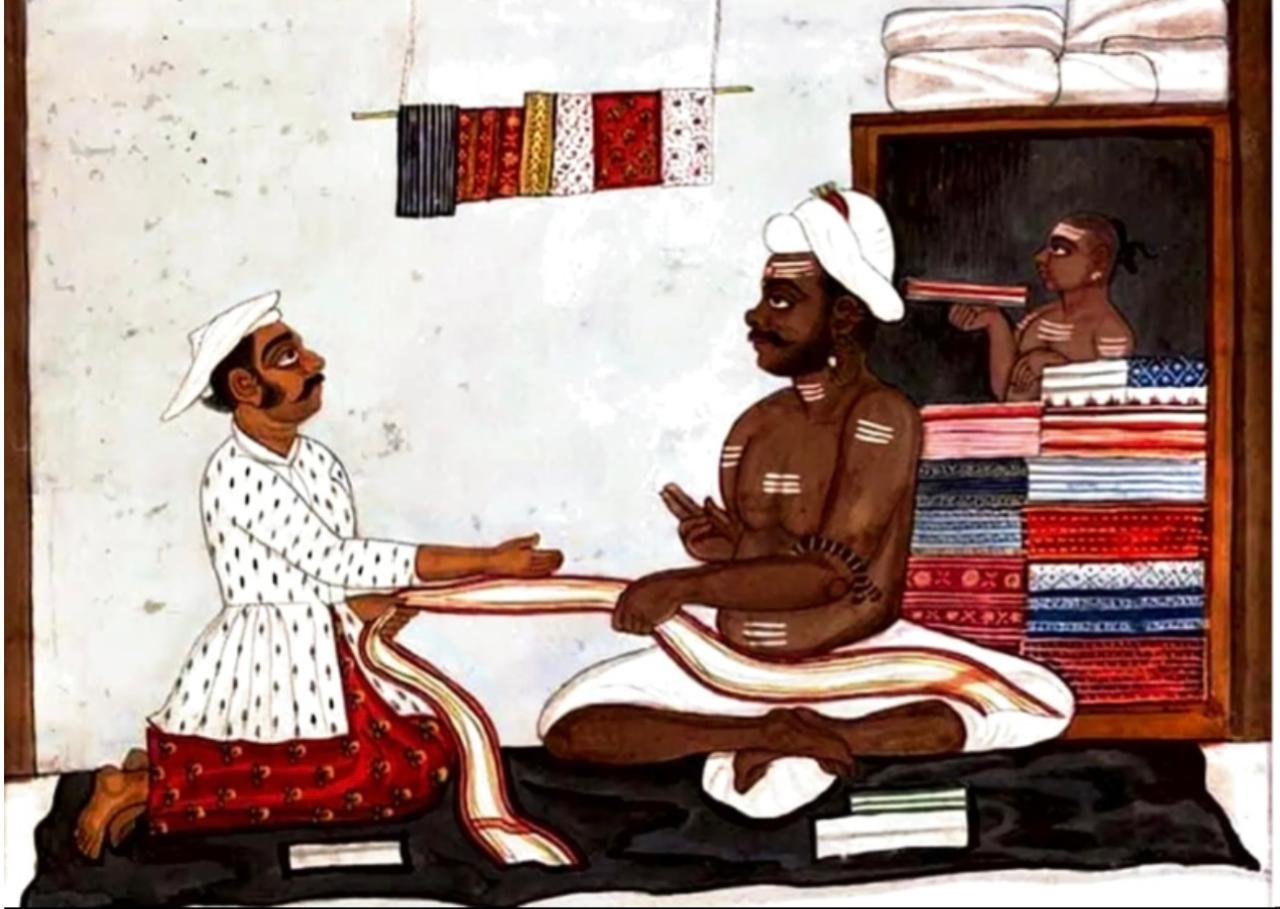

A cloth shop in 18th-century India. As early as the 10th century, one Arab traveler observed that “these garments … [are] woven to that degree of fineness that they may be drawn through a ring of a middling size.

Source : www.aramacoworld.com

A particularly poignant detail is the disappearance of the phuti karpas plant itself, which became extinct due to neglect. The intricate knowledge of spinning and weaving muslin, passed down through generations, was lost, plunging Bengal’s artisans into obscurity.

The Cultural Legacy and Modern Revival

Although Dhaka muslin disappeared from mainstream production, its cultural legacy endures. Museums like the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum preserve samples of the fabric, treating them as treasures from a lost era. The sheer beauty of these preserved pieces continues to inspire awe among visitors.

Many of the skills needed to make Dhaka muslin have been lost, so matching the quality of the original fabric is a challenge (www.bbc.com)

In recent years, efforts to revive Dhaka muslin have gained momentum. Bangladeshi researchers, after years of experimentation, successfully rediscovered the phuti karpas plant. ¹¹ Traditional weavers are now being trained to replicate the intricate designs and techniques of their forebears.

One remarkable modern initiative involved creating a six-meter-long Dhaka muslin sari, which took over six months to weave. This painstaking project demonstrated the dedication required to revive this ancient art form. ¹² Today, Dhaka muslin is being reintroduced as a luxury textile, offering hope that this legendary fabric will once again reclaim its place in the world of haute couture.

The Mesmerizing Magic of Muslin

Dhaka muslin remains one of history’s most extraordinary textiles, its story interwoven with themes of artistry, luxury, and resilience. From the imperial courts of the Mughals to the salons of Europe, it represented the height of cultural sophistication.

The decline of muslin serves as a somber reminder of the fragility of artisanal traditions in the face of industrialization and colonial exploitation. Yet, the ongoing revival efforts in Bangladesh are a testament to the enduring allure of this “woven air.”

Dhaka muslin was more than just fabric—it was a symbol of beauty, ingenuity, and human creativity. As it reemerges in modern times, it continues to captivate hearts, carrying with it the legacy of a bygone golden age.

REFERENCES

- Abul Fazl, (1590). Ain-i-Akbari. Translated by H. Blochmann. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- R. Gupta, (2001). “The Woven Air: The Lost Glory of Dhaka Muslin.” Journal of Textile History, 12(3), pp. 45-67.

- S. Chakrabarti, (2005). The Mughals and the Bengal Economy: The Glory of Dhaka Muslin. Kolkata: Bengal Historical Press.

- J. P. S. Uberoi, (1993). “Luxury and Status: The Role of Dhaka Muslin in Mughal Society.” Journal of South Asian Studies, 17(2), pp. 112-128.

- C. Banerjee, (2008). “The Decline of Dhaka Muslin: Colonial Exploitation and Industrialization.” Modern History Review, 26(4), pp. 83-102.

- M. S. S. Pandian, (2010). Fabric of Royalty: The Muslin Trade in the Mughal Empire. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- J. A. Thomas, (2014). “The Global Reach of Dhaka Muslin: A Study of Its European Appeal.” Textile and Trade Journal, 6(1), pp. 55-70.

- T. Ghosh, (2017). “Reviving the Lost Art: The Modern Revival of Dhaka Muslin.” Crafts and Textiles Quarterly, 34(2), pp. 22-36.

- P. Kumar, (2020). “The Role of Dhaka Muslin in Mughal Summer Fashion: Status, Luxury, and Prestige.” The Mughal Court Journal, 9(3), pp. 78-94.

- V. N. Gokhale, (2003). Colonial Exploitation of Indian Textiles: The Case of Dhaka Muslin. New Delhi: Indian Historical Press.

- 11.Elliot and Dowson, History of India as told by its own Historians, vol.1, London,1867, p.-5.