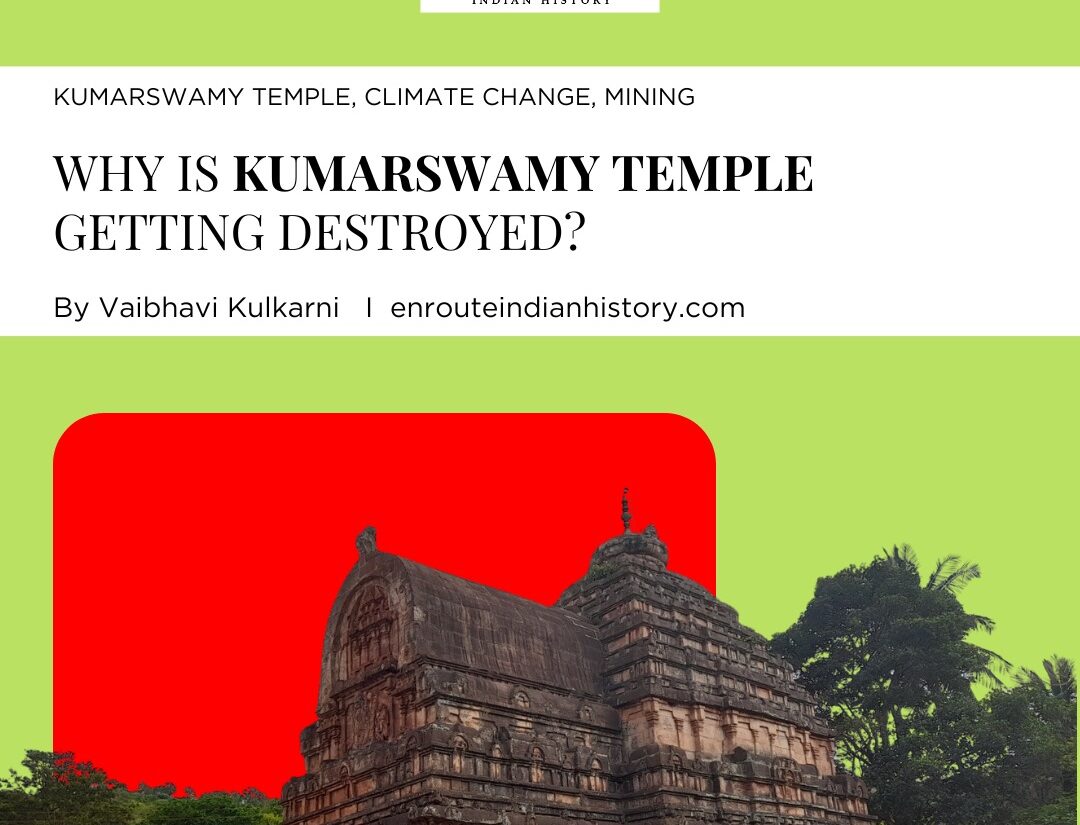

“From royal courts to forgotten weaves” the story of Dhaka Muslin

- iamanoushkajain

- May 16, 2025

The Craftsmanship of Dhaka Muslin

The delicacy of muslin cloth; Dhaka muslin came in thread counts up to 1,200, but the highest achieved in recent years is 300.

The extraordinary nature of Dhaka muslin stemmed from the phuti karpas cotton plant, which grew exclusively in the fertile plains of the Meghna River. This plant produced fibers so fine that they had to be spun during the early morning dew to prevent the delicate threads from snapping.² It is said that the finest muslin could only be woven by master artisans whose skills were honed over generations.

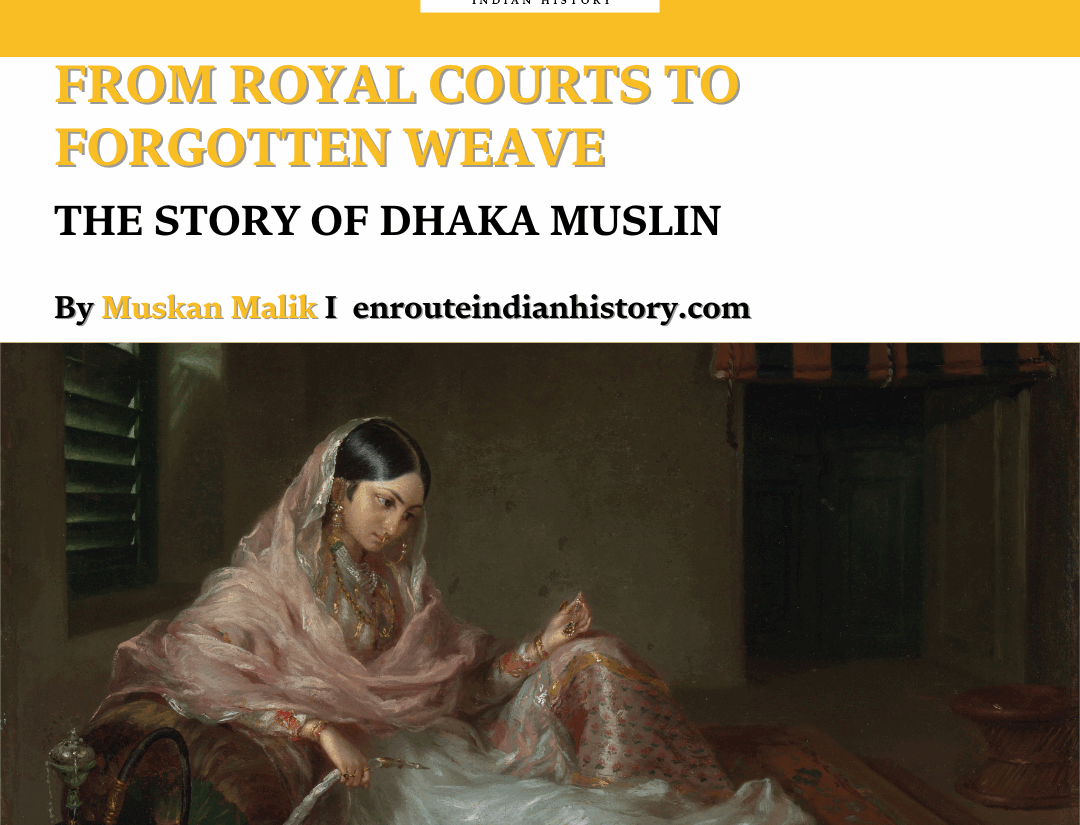

These artisans, known as tantis, wove muslin so thin and light that it was often described as resembling “clouds resting on the skin.” European travelers recounted that Mughal courtiers reprimanded female attendants for appearing unclothed, only to discover they were draped in several layers of muslin!³ The fabric’s transparency and ethereal beauty were unparalleled. Colin Thubron in his book had noted, “An Arab merchant in the ninth century was astonished to observe the mole on an imperial eunuch’s chest through five layers of gossamer silk.” The name of this Arab merchant was Suleiman. He wrote in his book, Silsiltu-T Tawarikh, about the (Dhaka) muslin, not about silk, that, “There is a stuff made in his country which is not to be found elsewhere; so fine and delicate is this material that a dress made of it may be passed through a signet-ring. It is made of cotton, and we have seen a piece of it.” 11. Varieties of muslin were given poetic names like abrawan (“running water”) and baft-hawa (“woven air”), further underscoring their otherworldly qualities. Entire garments made of muslin were known to pass through a ring, a feat repeatedly documented by historians and travelers.⁴

Muslin in the Mughal Court

Under the patronage of the Mughal emperors, Dhaka muslin reached the pinnacle of its prestige. Emperor Akbar meticulously cataloged various grades of muslin in his Ain-i-Akbari, reserving the finest, malmal khassa, exclusively for royal use.⁵ The fabric was an essential part of imperial wardrobes, particularly prized for its ability to provide relief from India’s intense summer heat.

Jahangir, Akbar’s successor, extolled the virtues of muslin, describing it as “dancing with the slightest breeze.”⁶ Royal garments made from muslin were often adorned with gold and silver threads, elevating the fabric to the height of luxury. One particularly fascinating tradition was the use of muslin in Mughal ceremonial practices. It was used to wrap imperial gifts and even sacred relics, symbolizing purity and grandeur. Its presence in religious and diplomatic rituals elevated its cultural importance, making it synonymous with refinement and prestige.

A mesmerizing anecdote from the Mughal court describes how veils made from muslin were so sheer that noblewomen seemed to vanish behind them, leading visitors to mistake them for being uncovered. This optical illusion only added to the fabric’s mystique.

Dhaka Muslin and European Aristocracy

The fame of Dhaka muslin spread far beyond the subcontinent, capturing the imagination of European aristocracy during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Portuguese were among the first to introduce the fabric to Europe, followed by the British East India Company, which turned it into a lucrative export.

Queen Marie Antoinette of France adored muslin gowns for their ethereal elegance. French nobility often wore dresses so light and transparent that they appeared to float.⁷ In Britain, muslin became a symbol of sophistication, with women showcasing its transparency during outdoor events. The phrase “muslin fever” was coined to describe the pneumonia outbreaks that followed these displays, as women braved cold weather in their thin muslin dresses.⁸

European poets and writers often likened Dhaka muslin to divine beauty. Some described it as “threads of moonlight,” while others compared its texture to the gentle touch of a cloud. Such descriptions reflected the fabric’s almost mythical status in European high society.

The Tragic Decline of Dhaka Muslin

Despite its global acclaim, Dhaka muslin faced a tragic decline with the advent of colonial rule and industrialization. The British East India Company imposed crippling taxes on Bengal’s weavers, forcing many into poverty.⁹ The once-thriving weaving communities, celebrated for their unparalleled skill, were systematically dismantled. Industrialization in Britain dealt the final blow. Mechanized textile mills in Manchester began producing cheaper, machine-made fabrics that flooded global markets, pushing handwoven muslin into obsolescence. Some historical accounts even suggest that British officials ordered the thumbs of master weavers to be cut off to eliminate competition, though this claim remains a subject of debate.¹⁰

A cloth shop in 18th-century India. As early as the 10th century, one Arab traveler observed that “these garments … [are] woven to that degree of fineness that they may be drawn through a ring of a middling size.

A particularly poignant detail is the disappearance of the phuti karpas plant itself, which became extinct due to neglect. The intricate knowledge of spinning and weaving muslin, passed down through generations, was lost, plunging Bengal’s artisans into obscurity.

The Cultural Legacy and Modern Revival

Although Dhaka muslin disappeared from mainstream production, its cultural legacy endures. Museums like the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum preserve samples of the fabric, treating them as treasures from a lost era. The sheer beauty of these preserved pieces continues to inspire awe among visitors.

Many of the skills needed to make Dhaka muslin have been lost, so matching the quality of the original fabric is a challenge (www.bbc.com)

In recent years, efforts to revive Dhaka muslin have gained momentum. Bangladeshi researchers, after years of experimentation, successfully rediscovered the phuti karpas plant.¹¹ Traditional weavers are now being trained to replicate the intricate designs and techniques of their forebears.

One remarkable modern initiative involved creating a six-meter-long Dhaka muslin sari, which took over six months to weave. This painstaking project demonstrated the dedication required to revive this ancient art form.¹² Today, Dhaka muslin is being reintroduced as a luxury textile, offering hope that this legendary fabric will once again reclaim its place in the world of haute couture.

The Mesmerizing Magic of Muslin

Dhaka muslin remains one of history’s most extraordinary textiles, its story interwoven with themes of artistry, luxury, and resilience. From the imperial courts of the Mughals to the salons of Europe, it represented the height of cultural sophistication. The decline of muslin serves as a somber reminder of the fragility of artisanal traditions in the face of industrialization and colonial exploitation. Yet, the ongoing revival efforts in Bangladesh are a testament to the enduring allure of this “woven air.” Dhaka muslin was more than just fabric—it was a symbol of beauty, ingenuity, and human creativity. As it reemerges in modern times, it continues to captivate hearts, carrying with it the legacy of a bygone golden age.

REFERENCES

1. Abul Fazl, (1590). Ain-i-Akbari. Translated by H. Blochmann. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal.

2. R. Gupta, (2001). "The Woven Air: The Lost Glory of Dhaka Muslin." Journal of Textile History, 12(3), pp. 45-67.

3. S. Chakrabarti, (2005). The Mughals and the Bengal Economy: The Glory of Dhaka Muslin. Kolkata: Bengal Historical Press.

4. J. P. S. Uberoi, (1993). "Luxury and Status: The Role of Dhaka Muslin in Mughal Society." Journal of South Asian Studies, 17(2), pp. 112-128.

5. C. Banerjee, (2008). "The Decline of Dhaka Muslin: Colonial Exploitation and Industrialization." Modern History Review, 26(4), pp. 83-102.

6. M. S. S. Pandian, (2010). Fabric of Royalty: The Muslin Trade in the Mughal Empire. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

7. J. A. Thomas, (2014). "The Global Reach of Dhaka Muslin: A Study of Its European Appeal." Textile and Trade Journal, 6(1), pp. 55-70.

8. T. Ghosh, (2017). "Reviving the Lost Art: The Modern Revival of Dhaka Muslin." Crafts and Textiles Quarterly, 34(2), pp. 22-36.

9. P. Kumar, (2020). "The Role of Dhaka Muslin in Mughal Summer Fashion: Status, Luxury, and Prestige." The Mughal Court Journal, 9(3), pp. 78-94.

10. V. N. Gokhale, (2003). Colonial Exploitation of Indian Textiles: The Case of Dhaka Muslin. New Delhi: Indian Historical Press.

11.Elliot and Dowson, History of India as told by its own Historians, vol.1,London,1867,p.-5..

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read