The majestic Yamuna is an ancient symbol of divinity and patience. Often compared to the bustling and violent Ganga, a spiritual representation of the same shows the goddess Yamuna standing on a tortoise, depicting her slow and steady pace. Yet, on the eve of 10th July 2023, the Yamuna lost her temperament and heavily spilt onto the streets of Delhi.

5th century terracotta sculpture of Yamuna with attendants (wikipedia)

For the past decade or so, there hasn’t been a lot of discussion around the Indian River, other than the constant shame of its pollution. Its significance, rich history, and cultural value have been overshadowed by the foul smell and chemical foam. The heavy construction around and on its floodplains have made it tumultuous and transformed it into a symbol of destruction. The same reached its apex with the recent floods as water levels of the Yamuna reached 208 metres, triggering extensive overflows. As the water gushed down the streets of Delhi, one couldn’t help but wonder if this was her attempt at reclamation.

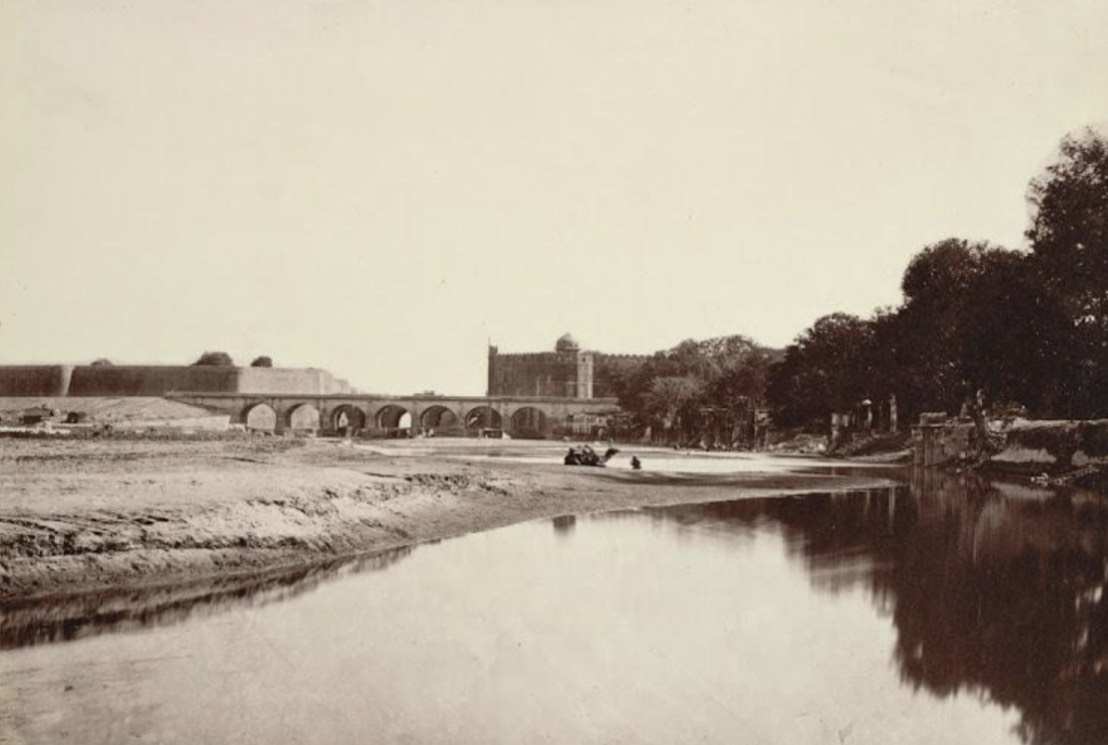

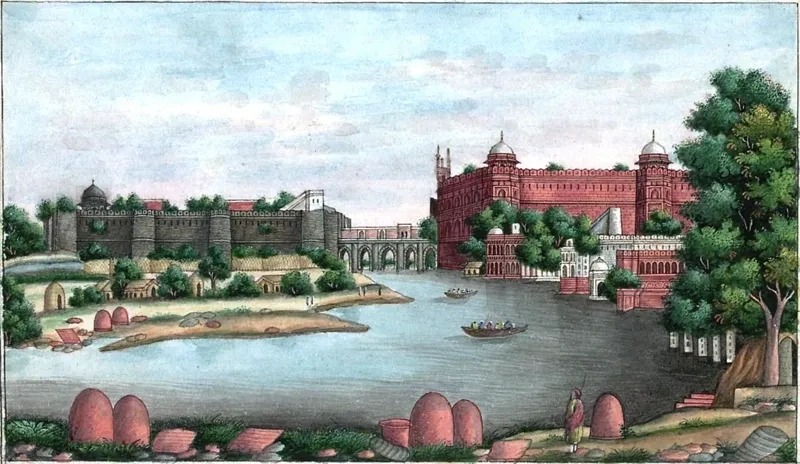

An old painting of the Bridge connecting the Salimgarh Fort and the Red Fort, shows a stream of water flowing underneath. This stream was an old channel of Yamuna that has since disappeared and is now replaced with roads and buildings, namely the Ring Road. The recent floods have, in a cyclic turn of events, brought the Yamuna back to the bridge. Similar situations have occurred across historic cities, seeing flooding that hasn’t been seen for decades, such as in Mathura and even Agra. This singular event has rehashed the discourse around the Yamuna, allowing it to be more than just a foul memory. Through this piece and the three cities, I hope to explore her past and refocus on the versatility of the Yamuna.

View that looks south along the river yamuna towards the Red Fort in Delhi, with the walls of Salimgarh on the left, connected by a bridge – 1860, Eugene Clutterbuck Impey, British Library

MATHURA AND INDIAN MYTHOLOGY

The Yamuna finds extensive mention in Hinduism and Indian Mythology. It is considered to be a holy river, crossing the religious city of Mathura. The city is believed to be the birthplace of Krishna, creating a strong connection between the god and the river. At the time of his birth, the Yamuna parted itself to create a path for Vasudev and infant Krishna. This allowed them to pass over to Vrindavan where Krishna spent his formative years playing by the riverside. It is also often referred to as Kalindi. This is due to the instance of Kali-naag where the serpent King Kalia poisons the river turning it black. Krishna then goes underwater and defeats Kalia, restoring Yamuna’s purity. The mythology also presents the two as lovers leading Yamuna to become Krishna’s wife, as depicted in the Bhagvat Puran. The Mahabharata shows goddess Yamuna being born to Sanjana, the wife of Surya the sun god. She is the twin sister of Yama, also known as Yamraj. Legend suggests that Sanjana was unhappy with Surya and secretly escaped the family by replacing herself with a stand-in named Chaya. Chaya was the embodiment of an evil stepmother, cursing Yama to the Patalok, making him Yamraj the god of death. This deeply saddened Yamuna who cried endlessly and her tears eventually formed the river Yamuna.

View of Vishram Ghat, Mathura, Kishore Dagia, Artmajeur Gallery, Pinterest

These stories and more make the river vital to the pious. Due to its connection to Krishna and the city of Vrindavan, it is believed that a dip in the river can purify one’s soul. The ghats of Mathura are home to various temples and preachers who hope to find religious value. It is also the site of various festivals and celebrations. Being a tributary of Ganga, it eventually meets the same at Prayagraj (formerly known as Allahabad). Scriptures suggest that this was also the place where the three main holy Indian rivers, Ganga, Yamuna and the mystical Saraswati, would intersect, giving the name Triveni Sangam.

AGRA AND THE AESTHETICS

There is a lot to say about the relationship of Yamuna with the people on her banks, but nothing is quite as grandiose as the Mughal royalty in Agra. As the Indian river jumps along the walls of the Taj Mahal, you can almost catch a glimpse into what the town used to be in its heyday. Starting from the very first emperor of the dynasty, Babur, the river has been a source of comfort for the regal. Records suggest that Babur had a deep disdain for the North Indian plains. The dust and wind made him yearn for the greens he had left behind in Kabul. Thus, he took advantage of the flowing waters of Agra, building marvellous garden enclaves on the banks of Yamuna. The famous Ram Bagh is a remnant of the same. This passion for gardens remained constant through generations, with the Mughals adding more gorgeous architecture both in Agra and also Delhi.

The Yamuna river in the city of Agra in Uttar Pradesh. The Taj Mahal can be seen in the background.

While in adjacent cities the banks seemed more like public or religious property, the Mughals in Agra took over, turning it into a personal haven. The Agra riverfront boasts of beautiful tombs and gardens that serve Mughal nostalgia and aestheticism. It provides the perfect grounds for a study of late mediaeval architecture and an insight into the royal minds.

DELHI AND CHANGE

The Yamuna and Delhi have been linked since time unknown. In the Mahabharata, the Pandavas capital city of Indraprastha is believed to have been in the same location as the modern city of Delhi. The ground has seen a very rich history with kingdoms coming and going, inhabiting various spaces. Undoubtedly, Delhi is a real cultural goldmine.

Salimgarh Fort (on the left) and Red Fort separated by the Yamuna River spill Channel (since closed and converted into a road) and linked by an arched bridge, as viewed from Metcalfe’s townhouse, View of 1843 (wikipedia)

Going back to the image we started from, Salimgarh Fort was built by Salim Shah Suri, the son of Sher Shah Suri, in 1546. It existed long before the Mughal occupation, situated on what used to be a small island in the middle of the Yamuna. There were strategic reasons for the same such as the natural water barrier created. Less than a decade later, the Sur Empire came to an end as the Mughal emperor Humayun reclaimed his lost territory. In an attempt to humiliate the Sur dynasty, he renamed the fort as Nurgarh. It was used as the residence for the visiting Mughal emperors and even served Shahjahan as he built the Red Fort. In 1622, Jehangir built a bridge in front of the south gate of Salimgarh, going over the Yamuna connecting it to the opposite river bank. Later, Aurangzeb converted the fort into a prison, an activity perpetuated by the British. In 1647, Shahjahanabad was completed and Delhi became the official Mughal capital. Rana Safvi, the author of “Shahjahanabad: The Living City of Old Delhi”, writes about the choice between Delhi and Lahore. Both cities were contenders for the new capital but Delhi won precedence due to the Yamuna. The river allowed better transportation, provided water for the city and played a role in keeping the weather cooler. Shahjahanabad had 14 entry gates, out of which Khisri Darwaza was the only one situated by the river. The door was named after Khwaja Khisri, a man known as the “Sindhi saint of water”. In an interesting coincidence, this was the gate through which Shahjahan first entered the fort in 1647, and also the one through which the last emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar escaped in 1857.

Eventually, the city came under the control of the British Empire which started much of the modern development of Delhi. They considered creating their infrastructure by the floodplains but were discouraged by the shifting water levels. There is no doubt that the Yamuna played an important role in shaping the history and planning of Delhi, though more recently its cries of caution are left unheard. As the city expands, the legroom for the river reduces. The rich make their fancy colonies overlooking the spectacle while the poor, attempting to make a living from the same, base themselves close to her volatile shores.

Despite its illustrious history, the meaning of Yamuna is now definitely lost. As it trudges down Gangotri, the water is exploited and mistreated. Yamuna is now a dumping ground. Over the past two decades, with the rapid development of industry and infrastructure all around it, the Yamuna is falling victim to pollution. Those who hoped to sustain themselves from her are getting sick and those who hope to purify themselves are getting more sick. The constant creation of dams and barrages is hindering her flow and testing her patience. Thus the flood-like situations of today. It is almost as if Kalia the Serpent King has returned and turned the Yamuna black again. The question remains, is there a Krishna who can save it?

REFERENCES

- Harkness, Terence. Sinha, Amita. (2004) ‘Taj Heritage Corridor: Intersections between History and Culture on the Yamuna Riverfront’, Places, 16(2)

-

- Haberman, David. (2006), ‘River of Love in an Age of Pollution: The Yamuna River of Northern India’, University of California Press

- Joshi, Mallica. (2023), ‘Delhi’s relationship with Yamuna river and how it evolved over time’, The Indian Express

- Shah, Bidisha. (2023) ‘Yamuna deluge in satellite pics: Taj Mahal, parts of Mathura, Agra, Vrindavan submerged’, India Today

- Kumar, Kunal. (2023) ‘Yamuna reclaims old course as water reaches Red Fort wall. What historians think’, Hindustan Times

- September 6, 2023

- 6 Min Read

- September 4, 2023

- 6 Min Read

- August 12, 2023

- 9 Min Read