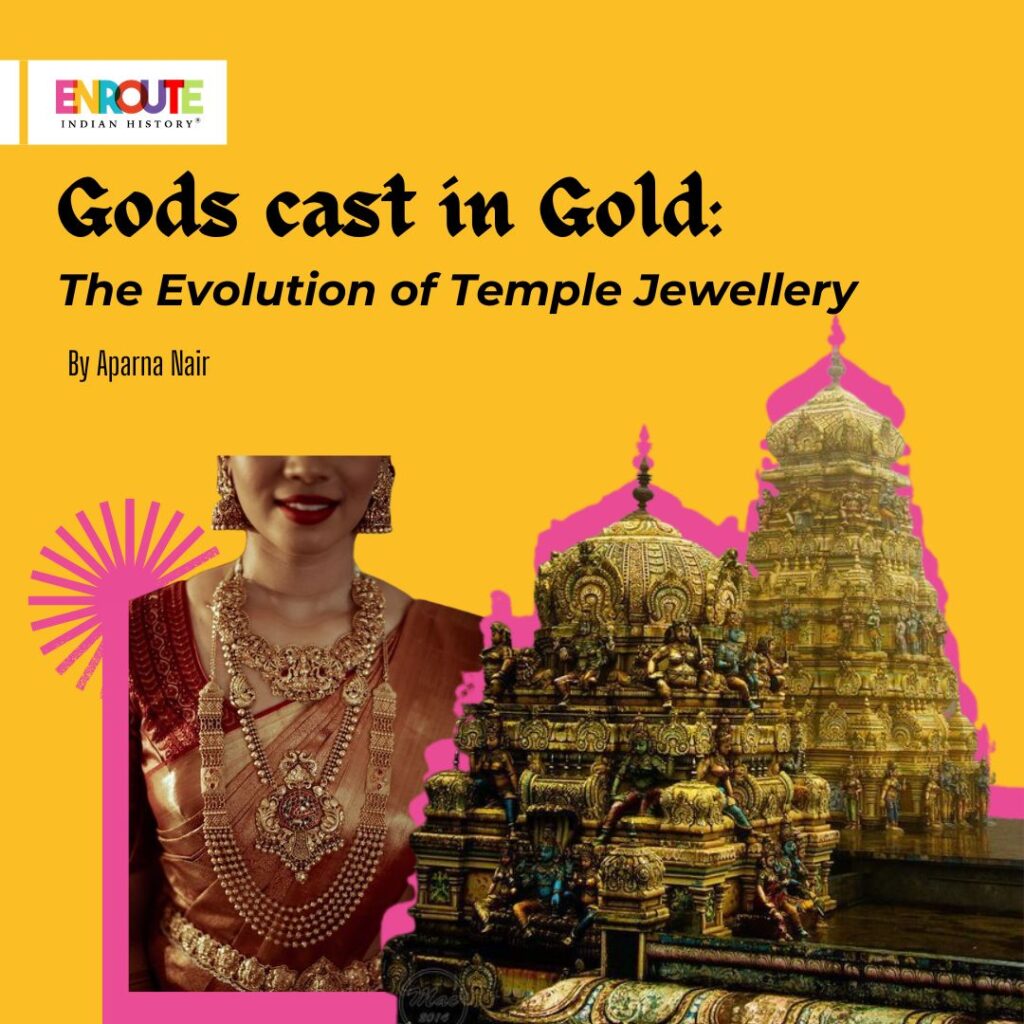

India has a rich history of making gold jewellery which traditionally links the past and present generations together. In South India, temples have been centres of worship and wealth where rituals and lavish offerings to appease God, especially with gold and gems, signify the pride and prosperity of the donees and Rajas. One such form is temple jewellery, which originated in South India and is currently in vogue among the rich classes.

EVOLUTION OF GOLDEN TEMPLE JEWELLERY

- Dandapani traces the origins of temple jewellery to the 9th-century Chola kingdom, and Usha Bala Krishnan notes that highly skilled artisans crafted it as an offering to the Gods in temples to adorn them. In Kerala, it is known as thiruvabharanam. Pilgrims or donees (like Rajas) would offer such jewellery made of pure gold to seek divine intervention or the fulfilment of their wishes. This could only be created by a few pattans (goldsmiths) and asaris (jewellers), such as those of Vadassari, a place in the southern tip of Tamil Nadu bordering Kerala; thus, the temple jewellery is also known as Vadassery (or Vadasari) or Kemp. It includes earrings, necklaces, wristlets, bracelets, armlets, headgear, masks, tali (mangalasutra), and kasinara (chain of coins).

With the coming of the Devadasis (literally, ‘servants of God’) as brides of the deities, in Tamil Nadu, temple jewellery such as the thalaisaaman (head ornaments) with elaborate carvings set in stones was used. With the evolution of dance, particularly Bharatanatyam, it went out of temples, and so did temple jewellery. The dance form patronised the jewellery, which is still used today, but mostly made of artificial materials.

Image 1: A Bharatanatyam Dancer adorned with artificial temple jewellery. Notice the belt around the waist with several circles – it represents Lakshmi, Ganesha, and Saraswati. (Image of the author)

MAKING OF THE TEMPLE JEWELLERY

Since the objective of the jewellery was religious, the images were of the Gods and Goddesses, but made in gold. Images of Shiva linga, Nandi, Lord Sundareshwara, goddess Meenakshi, Lakshmi, Gajalakshmi, Garuda Sina Vishnu, Kaliyakrishna, Venugopala, and Dashavatara are popular images used in such ornaments. Animals such as the serpent (symbolising birth and rebirth), the lion (for strength and courage), and the elephant (related to fertility) are also used. The fish represents Lord Vishnu’s matsya avatara and is one of the ashtamangalas (eight of auspiciousness). The peacock signifies immortality and love and is also the vehicle of Lord Karthikeya.

Manga malai (mango necklace), which is believed to be a symbol of fertility and is part of the temple as well as the bridal jewellery.

A parrot pendant, which, according to Hindu mythology, represents love, and Lord Kamadeva’s chariot, which is also drawn by parrots.

The reason for using gold in such jewellery is that it does not oxidise and tarnish like other metals and can be worn against any skin. Representing the goddess Lakshmi, gold is considered sattvik and auspicious and destroys harmful germs in the body. Hindus believe it to be sacred and is a symbol of status, authority, health, wealth, and prosperity. So, gold is used with precious and semi-precious stones like uncut diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires. Ruby is considered the “king of precious stones” and symbolises wealth and prosperity; emerald is considered to protect against evil eyes; sapphire ensures prosperity and immunity from death. Sometimes, the nava ratna (nine gems) is also used as a symbol of auspiciousness.

The process of making temple jewellery is known only by a closed community of craftsmen in Vadassari and is passed from father to son and so on. It is a lucrative business due to the high demand for temple jewellery even today. Khatib Hasina opines that the process would begin with making dyes and moulds of motifs, followed by rolling gold and silver rods into flatter shapes and cutting and bending them to the desired shapes. Later, it was sent for soldering (joining two metals using a solder) and a layer of gold foil was used as a cover to provide lustre to the piece. In the past, Rayachoti S.R. notes, Cabochon (cushion-shaped) rubies were used, which were procured from Burma, and the pure gold used had a deeper significance to the people of those times. But temple jewellery also existed in other regions, such as in northern and western India. Necklaces and pendants with the motifs of Krishna and Radha are very popular.

An 18th-century mukut (crown) from Lahore with floral patterns and four chains and four squares attached at the bottom which costs around Rs. 10 to 11 lakhs.

A gold armlet or bajuband with Lord Krishna’s motif, dating to the early 20th century.

A Radha-Krishna necklace with rubies and gold leaves dating to the 20th century in Kapurthala, Punjab, and carvings of Lord Ganesha and a goddess on the reverse.

IN THE PRESENT TIME

Given the current rate of gold per gram, which is Rs. 5425 for 22 carats per gram of gold and Rs. 5918 for 24 carats per gram of gold, and the high labour charges for making such jewellery, several changes have been brought to its making. Unlike the temple jewellery of the past which was heavy, today it is made of several other metals and designs to reduce its weight. Many of the jewellers use silver as the base metal and coat it with gold foil. Silver symbolises the moon and signifies protection against magic and helping with good dreams and intuitions. The stones used are artificially manufactured and designed to suit people’s tastes. The process of finishing and polishing is also done by machines nowadays. Therefore, India has crafted gold jewellery not only for the people but also for the Gods, exuding divinity. Though it was once meant to be a garland for the gods, it has now turned into a garland for the prosperous, and it is less about devotion and more about design. Yet, gold’s significance in Indian jewellery is not to be undermined, as it continues to be the most important component of beautification.

REFERENCES

Articles

- Appadurai, A., Breckenridge, C. Appadurai. “The south Indian temple: authority, honours and redistribution.” Contributions to Indian Sociology (NS), vol. 10, no. 2, 2018, pp. 187-211.

- Dwivedi, J. “Indian tribal ornaments; a hidden treasure.” Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology, 10(3), 2016, pp. 1-16.

- Jain, Neeru. “A Temple Jewellery – A Rich Heritage of India.” IIS University Journal of Arts, 11 (1), 2022, pp. 380-86.

- Yothers, Wendy., Gangadharan, Resmi. “Narration on ethnic jewellery of Kerala – focusing on design, inspiration and morphology of motifs.” Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology, 6 (6), 2020, pp. 267-274.

- Rajgor, Dilip. Heritage of India. Rajgor’s Auctions NGS of India Pvt. Ltd., 2013.

- Kaur, Prabhjot., Joseph, Ruby. “Women and Jewelry – The Traditional and Religious Dimensions of Ornamentation.” ResearchGate, 2012.

- February 22, 2024

- 8 Min Read