Hiranyagarbha: The Ritual of Donating Gold & Claiming Superior Caste.

- enrouteI

- July 12, 2023

The term Hiranyagarbha translated as the ‘Golden womb’ encapsulates the tale of the origin of the universe as described in the Vedic philosophy. The Hiranyagrbha sukta of Rigveda elaborates how Svayambhu, meaning self-born (a term used for many Hindu deities) transplanted the golden seed i.e. Hiranyagarbha in the water through which life emerged. Over time, this term came to be used as an epithet for Brahma. However, this tale of the creation of the universe through a ‘Golden womb’ led many Hindu Kings in India, to recreate the scene through the performance of a ritual termed as “Hiranyagarbha.” The ritual of Hiranyagarbha is described in Ballalasena’s Danasagara as one of the sixteen most auspicious ‘Dana’ or donations in which a Golden Vessel termed as ‘Kunda’ measuring around three cubits in height or more was given away by the King to the Brahmana.

Painting of the Golden womb Hiranyagarbha by St. Hildegard of Bingen 12th c.

While giving donations is not an unprecedented practice. Gold since time immemorial has been an indicator of prosperity and class status for many rulers in the Indian subcontinent. The uniqueness of the Hiranyagarbha ritual lies in the donation of gold to the priest with a particular aim, which is to upgrade one’s caste status. In a deeply fragmented and hierarchical Indian society in which the claim to a superior caste status is so entrenched and essential. Many Hindu kings with obscure caste origin contemplated the Hiranyagarbha ritual as necessary to secure their social standings and legitimize their rule. Inscriptional evidence especially from Deccan and South Indian Hindu Kings frequently reiterates the term ‘Hiranyagarbha’. For instance, the Gorantala inscription mentions King Attivarman of the Ananda dynasty (4th century) as “Hiranyagarbha-prasava” which has been translated by Prof. D.C Sircar as ‘born of the golden womb’. Another example is the Mahakuta pillar inscription of the Chalukya king Mangalesha which describes him as“Hiranyagarbha-Sambhutam” which has been translated by Fleet as ‘descended or produced from the golden womb’. Pulakeshin I (c 550), of the Chalukya dynasty, is also known to have performed the Hiranyagarbha to establish greater sovereignty.

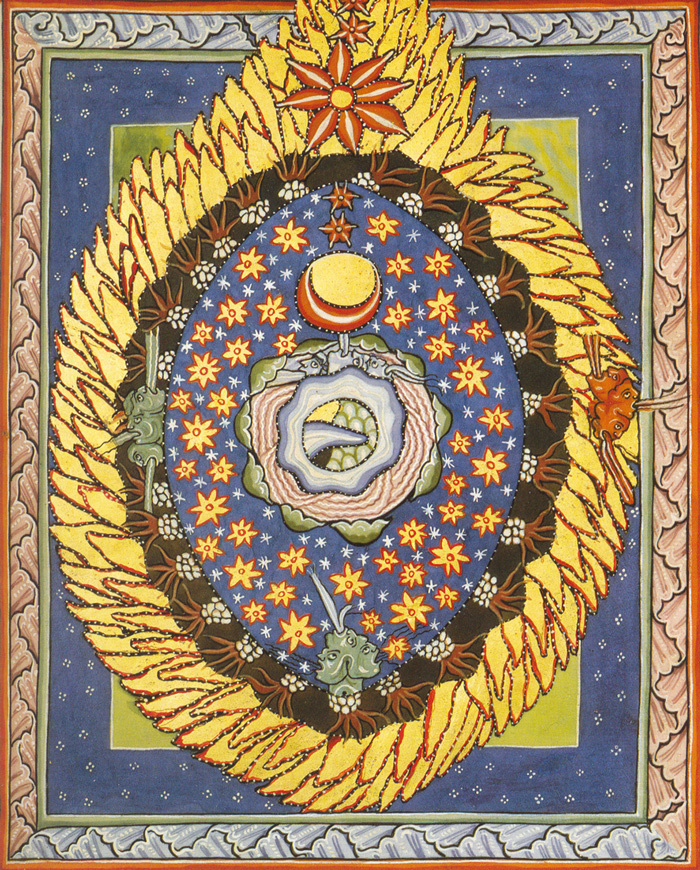

In encountering these fascinating inscriptions, it’s almost incontrovertible that despite such connotations, no king can be born out of a golden womb. Hence, the Golden womb here refers to the gold Kunda which was used to perform the Hiranyagarbha ritual. At the initiation of the Ceremony, as described in the Matsya Purana, the donor would perform a prayer chanting mantras in reverence to the lord Hiranyagarbha, Lord Vishnu. Following that, the Donor (i.e. the King) enters the hollow Gold Kunda. The entire ritual was performed imitating both the process of birth which is the birth of the universe from the ‘Golden womb’ and the birth of a child from a pregnant woman. While the donor stays inside the Gold Kunda, the priests perform the ceremonies of Garbhadhana, Pumsavana, and Simantonnayana in the same way as performed in the case of a pregnant woman. Then the Donor is taken out of the Gold Kunda and the ritual of Jati-Karman is performed as in the case of a newborn.

(Source: Historic Alley; Picture depicting a procession of the Golden Vessel)

The Raja emerging out of the Gold Vessel after the ritual’s completion was regarded to have taken rebirth into a higher social order. It is related to the concept of twice-born or Dvija, a status awarded to the first three varnas in the hierarchy. Hereby, attaining a higher caste status. The Performer of the Ritual then chants a mantra that reiterates the fact that he has transformed himself from “Martya dharman” meaning someone possessing the qualities of an earthly creature to one having “Divya-deha” i.e. divine body. Ritual’s Completion was followed by the donation of the Gold vessel and other jewels to the priest. In some cases, the vessel made was so grand in size that it was broken and then the Gold worth was distributed to the Brahmanas.

The process underplaying the performance of this elaborate ritual of donating Gold among Kings has been suggested as ‘Acculturation’ by Prof. D.D Kosambhi in his work titled ‘The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline’ (1965). Kosambhi argues that many South Indian Kings with tribal origins performed this ritual not only to enhance their caste status but to attain a caste in the first place, which was not similar to the rest of the tribe. Most often this was a Kshatriya caste with a Brahmin gotra. In rare instances, both Brahman and Kshatriya status were claimed together in the case of several ‘reborn Hindu Kings’ such as in the case of Sathavahana Gotamiputra.

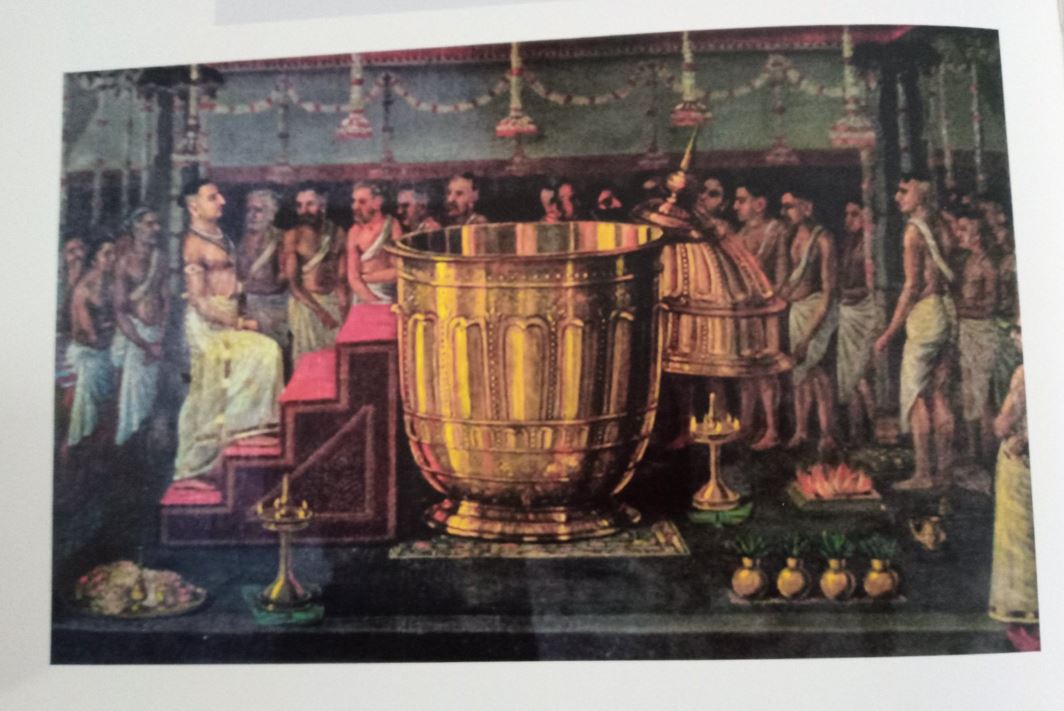

An artist’s representation of the Hiranyagarbha Ritual

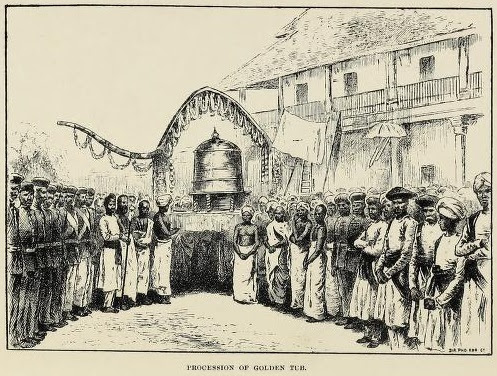

The most interesting illustration of the Hiranyagarbha ritual could be traced to the Royal family of Travancore. The Anthropological and sociological study accounts of the Rajas of Travancore reveal that they were of mixed race i.e. although being Samantha Nairs, they also traced their lineage from Cheras. To establish this Chera lineage and attain a higher caste status, they performed the Hiranyagarbha ritual. Samuel Mateer (1871) described this ritual as a “Regeneration Gift”. After the ritual was performed the Travancore kings could not dine with the rest of their family as they were now higher in caste status and hereby gained the ‘privilege’ to be in the company of the Brahmanas. Almost all Travancore kings performed this ritual, the written description of the same by Sreeneevasa Rao detailing how Late Raja Marthanda Verma performed this ritual is quintessential to our understanding. The proceedings were marked with the King retiring from his ordinary residence to a secluded space with no attendants belonging to the low castes. It also mentions how apart from the gold kunda, the king would also donate all the jewels and gold which he was wearing during the performance of the ritual to the chief priest. Apart from the Brahmans, numerous petty chiefs and nobles also attended the ritual. All of them also received the donation of gold coins made out of the same gold kunda.

After the ritual is completed, the Travancore King visits the idol of Sri Padmanabhaswamy and prostrates before it. He is then awarded the grandeur title of “Kulasekhara Perumal” which is translated loosely as the ‘Golden Lord’ or ‘Head of the tribe’, it is at this time that the chief priest coronates the Travancore with the ‘Kulasekhara Perumal crown’. Apart from the time of coronation, the Kings of Travancore do not wear this crown and after the ritual, it is again placed with the gold treasures of the temple. Through these gold donations, the king of Travancore marked his royal road to regeneration. However, by no means was the newly ‘born’ king’s caste status hereditary. This implied that every new king had to perform the same ritual of donating a gold vessel to be a Kshatriya. While this variability in caste status was a strain for the Travancore kings, the Brahmans on the other hand would significantly gain from this practice. As each new king meant repeating the same ritual, which would provide them with a vast amount of gold donation. C.J Fuller in his work titled The ‘Internal Structure of the Nayar Caste’ (1975) suggests that the greed for gold became so proliferated among the Brahmans that at times they would hatch conspiracies to do away with an ailing king.

(Source: Historic Alleys; Scene displaying Travancore King Marthanda Verma entering the Golden Vessel)

It was reportedly stated that the total cost of the Hiranyagarbha ritual was Rs. 3000,000. Furthermore, it has been stated that during the reign of Travancore king Marthanda Verma, when the Dutch came to the highness for a pepper trade agreement, he reportedly demanded 10,000 Kajinches of gold in exchange for pepper. This money was then used to perform his Hiranyagarbha ceremony. The echo of such an elaborate, expensive, and eerie ritual spread far and wide. The Britishers found such acts of donations not only economically straining but also against the Christian doctrines, such a view was reported in the famous ‘Sunday At Home’ magazine of London in its edition published on 1st of July, 1870. Infuriated by the aggravating financial condition of the Travancore kingdom, Lord Harris of the Madras presidency was ordered to warn Marthanda Verma, the then Travancore king, to put an end to such huge gold donations otherwise, the British Madras presidency would be forced to take over his kingdom. The last reported Hiranyagarbha ritual and the gold donation comes from Sri Moolam Thirunal, after which the practice was given up by Maharaja Chithira Thirunal of Travancore on the pretext of it being too expensive.

An end to the ritual of Hiranyagarbha didn’t imply that all practices related to gold donation came to a halt. Ceremonies such as Tulapurusha in which the king was weighed against jewels continued to be practiced. All these awestriking rituals highlight the importance of gold as a symbol of purity and power. Caste which remains a troubling question in today’s society was changed as per the King’s pleasure, given they showered wealth upon the Brahmans. While for the common populace who could not afford a gold vessel, caste remained an excuse for oppression.

REFERENCES

D.C Sircar, (1971). Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India. 1st ed. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

- Kosambhi, (1965). ‘The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline’. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Mateer, (1871). The Land Of Charity: A descriptive account of Travancore and its people, with special reference to missionary labor. 1st ed. London: John Snow & CO.

- Mateer, (1883). Native Life In Travancore. 1st ed. London: W. H. Allen & CO.

- J. Fuller, (1975) ‘The Internal Structure of the Nayar Caste’, Journal of Anthropological Research, 31(4th ed.), pp. 283-312. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3629883

- April 18, 2024

- 5 Min Read

- April 18, 2024

- 7 Min Read