Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Bhavya Saini

The discovery of textiles can be dated back to the ancient era, as early as Indus Valley Civilisation through various excavation sites. Researchers and archaeologists also attribute the rise of Indus Valley Civilisation to the development in the textile craft. While the wealth from the success of the textile craft has not survived the ravages of time, archaeological finds help us to understand the growth of the craft during the Indus Valley Civilisation. Evidence of dye vats along with cotton fragments at Mohenjo-Daro and remains of spindle whorls of stone, clay, metal, terracotta and wood at various sites including Harappa, Chanhudaro, Lothal and Kalibangan suggest that the ancient dwellers had developed the techniques of dyeing and spinning fabrics. A number of needles have also been found at these sites pointing towards the knowledge of sewing. The famous Priest King figurine at Mohenjo Daro depicts a man wearing a robe over one shoulder which suggests that the art of fabric decoration was also practiced during the Indus Valley Civilisation. In fact, the earliest evidence of cotton at sites like Harappa and Mohenjo Daro suggest that it may have been first cultivated and transformed into fabric there! Over the centuries, cotton became a significant economic and trade component of India amounting to 25% of the global cotton production. Its popularity can be attributed to not only its properties but also to its adaptability to the global trends, amongst which, Chintz is one such variety.

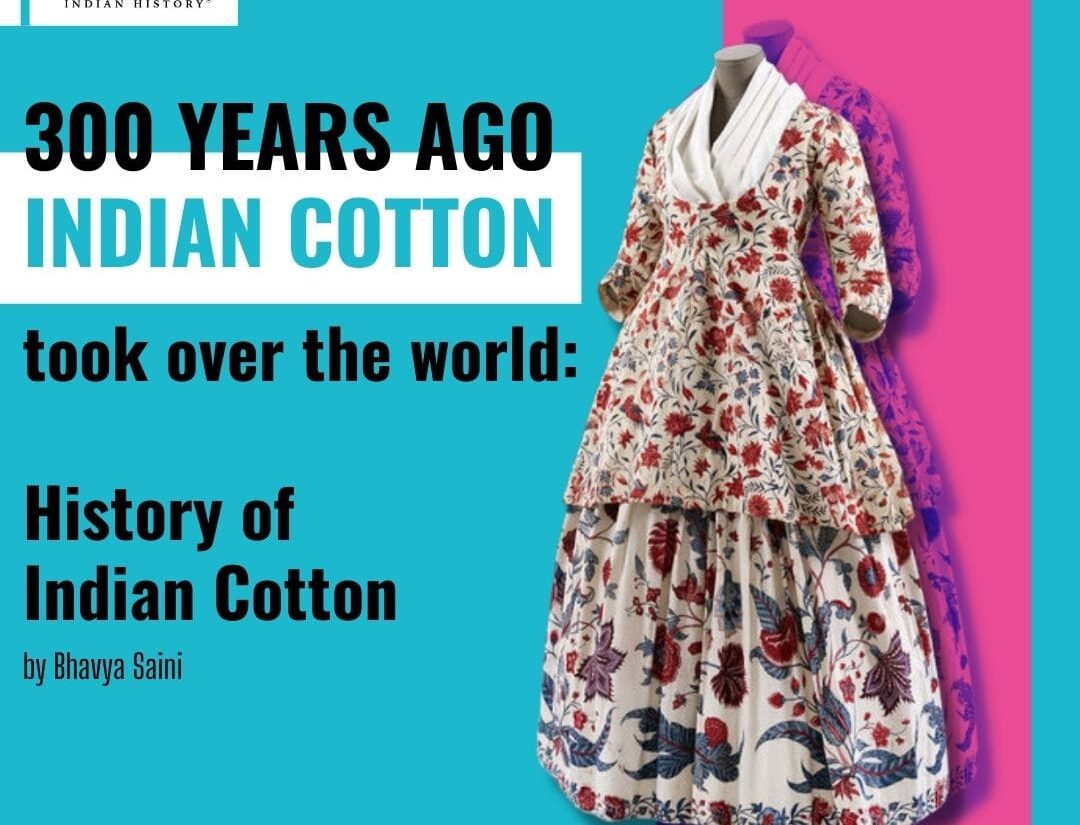

In contemporary times, Chintz is associated with any floral fabric but once dwelling deep into it, one discovers how it is often sold in a Europeanised form which once had strong Indian roots. Although contrary to the common belief, it has nothing to do with floral prints. “The term was appropriated in [the] English-speaking world in the 18th Century to reference industrially printed cottons,” Sarah Fee, an exhibition curator at the Royal Ontario Museum mentioned further adding, “In popular imagination, over the 19th Century, the term became associated with floral designs and heavy glazing.” The word ‘Chintz’ is derived from the Hindi word ‘chint’ or ‘chitta’ which means spotted or variegated. What made it stand out in the Indian as well as European market was the resist dyeing technique used in its production. Furthermore, the designs were hand-crafted with a bamboo pen known as ‘kalam’ and thus coined the local term ‘kalamkari’. By the 17th century, the fabric was so popularised among the Europeans that it was shipped to London where it became a huge hit. There, Chintz was not only used as a fabric but its beautiful patterns and technique found its way to the upholstery, so much so, it was believed that Queen Mary had decorated a bedroom with calicoes (a type of cotton imported from India) which increased the use of Chintz in furniture. According to researchers, Chintz was used in rather feminine settings as it was considered “an informal fabric”. Yet the popularity of Chintz in the global arena can only be credited to Vasco Da Gama who not only discovered the rich taste of Indian spices but also took with him a fabric that would influence not only the fashion trends but also have a significant impact upon history.

Even the fabrics that are believed to have European roots have Indian descendancy. With its increasing demand, the English merchants began to produce imitations of Chintz which was then a symbol of luxury and pride. These imitations were sold to rather lower classes to meet the demands of the common people and make a profit in an otherwise-hit textile industry in England. In 1851, English novelist George Eliot, in her letter to her sister mentioned, “The quality of the spotted one is best, but the effect is chintzy,” referring to one such imitated Chintz item. “By that time, Britain’s factories had flooded world markets with cheap imitations of chintz, industrial imitation [which made] it widely available to the masses, disassociating any original connotation of luxury,” Sarah Fee mentioned. The demand for Indian textiles was reaching skies eventually making the English textile merchants and artists vulnerable for survival. For this reason, many Chintz items were banned in England but men and women of fashion continued to wear Chintz fabric regardless as it was smuggled to Europe. In the 17th century, the Indian manufacturers were instructed to design the fabric more suited to the English preference. While Indian Chintz was worn mostly by the aristocracy in France, in England, it found its way to the richer classes much later, after it had been adopted by the working women. Fee remarks that there were rules against the masses wearing silk, but not cotton. Thus Indian Chintz emerged as “the first mass fashion” since it was worn by all classes.

Chintz Petticoat and Jacket

Along with being a cultural and economic blockbuster in Europe, Chintz can also be associated with multidimensional aspects such as tastes, aesthetics, techniques, fusion of influences, economic implications and political stability of governments. Even though the Chintz trend started to fade out around the 19th century, it has made several comebacks in fashion and design ever since, during the hippie culture of the 1960s for instance. If not entirely in fashion, it did remain prominent in popular culture with Eliot’s coinage of the term ‘chintzy’ often used to denote antique floral designs or “to evoke images of “your grandmother’s curtains” as quoted by Fee. More recently, the fabric, design as well as technique is used by many contemporary Indian designers with the rise in Indo-western fashion as an attempt to support home-grown labels. Fashion and textile researchers have also noted that varieties of Indian Chintz like Ajrakh are often spotted during Fashion shows like Lakme Fashion Week or even casually, on the displays of metropolitan malls of India. Even though Chintz is largely associated with highly priced floral patterns or antique furniture and wallpapers, it revolutionised the fashion industry and continues to remain equally relevant and trendy as before. However, Harvard Historian Dr Sven Beckert remarks how the story of Chintz is rather an unpleasant one highlighting “A tale of armed trade, colonialism, slavery, and the dispossession of native peoples.” For many centuries and even in the contemporary times, Chintz and its technique is often associated with European fashion trends discrediting the Indian artists and manufacturers all this time. The artists accept foreign motifs (the Chinese-inspired flowering trees, for instance) and mould them into their own aesthetics to provide an exotic touch. The resilience of the painters, their thought of innovation while preserving an age-old tradition, is what makes it unique and attractive.

References

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200420-the-cutesy-fabric-that-was-banned

https://indianculture.gov.in/textiles-and-fabrics-of-india/history

https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/fabric-of-india/guest-post-indian-chintz-a-legacy-of-luxury

Picture Credits:

Victoria and Albert Museum