Article by EIH Researcher and Writer

Ankana Das

With the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus, every workplace now has to abide by the mask mandate. The urban population though not quite happy about it, seem to have accepted it as a part of normalcy. On the other hand, in non- urban areas, especially in remote villages, the mask haven’t quite made a mark in people’s daily lives. However, in the villages of the Sundarban the use of masks always held an altogether different meaning.

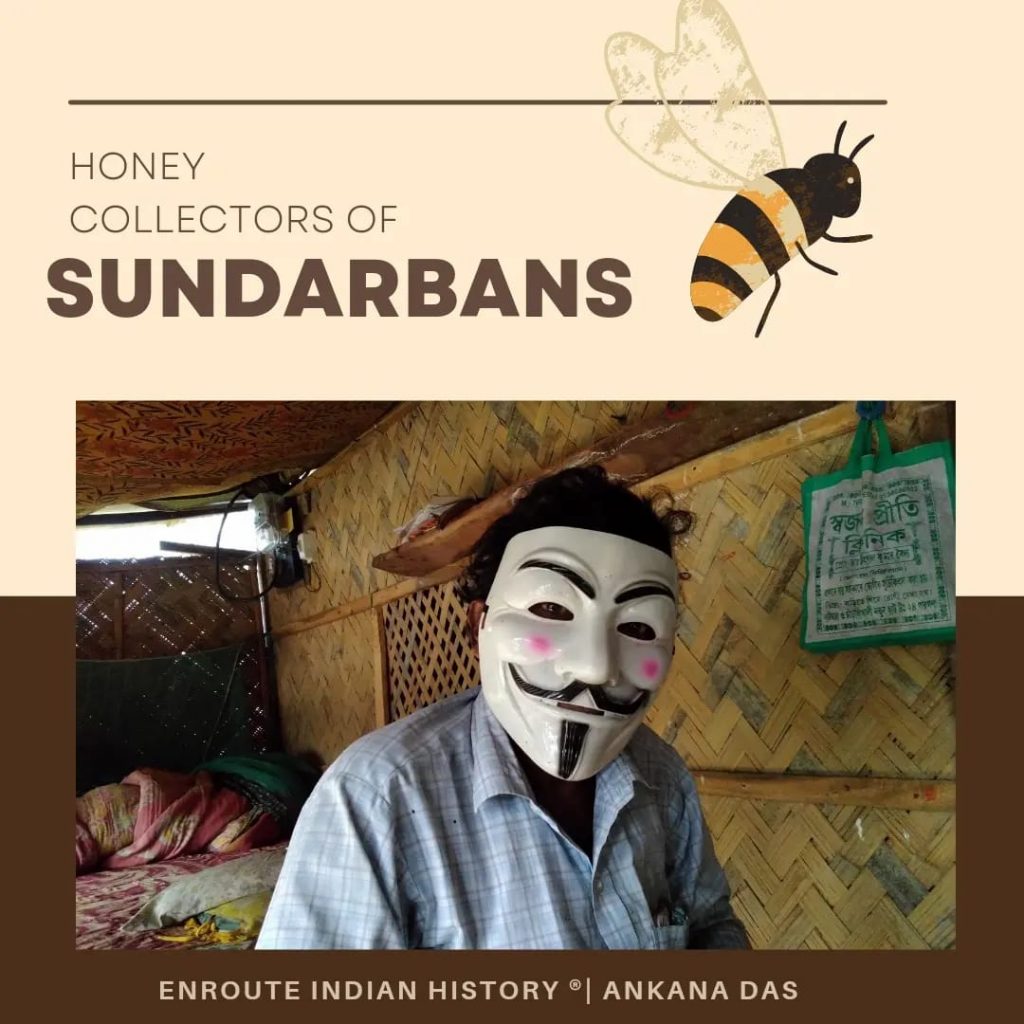

The Sundarban is a deltaic lowland situated at the mouth of the Bay of Bengal, spanning throughout the southern part of the Indian state of West Bengal and the Khulna district of Bangladesh. The forest dependent people of the Sundarban make use of forest resources such as timber and honey, and also fish from the numerous rivers running through the landscape. However, their interaction with nature is often laced with violence. As is widely known, the Sundarbans is famous for its most ferocious Royal Bengal Tiger, also the national animal of India, which happens to maul humans on a regular basis. An approximate 200 humans are killed by tigers in the Sundarbans every year. To combat this violent phenomenon, islanders and researchers together have always tried to understand the nature of tiger attacks. A myth ran its course among honey collectors who had to venture deep into the forests that the tiger always attack from the behind. Building up on this narrative, in the year 1986-87, the government of West Bengal decided to distribute face masks to honey collectors, which are to be worn on the backside of the head, in an attempt to trick the tiger in believing that the human is facing him. These masks are nothing of the sort we understand as mask in the times of this Covid- 19 pandemic. The honey collectors’ masks resembled roughly the human face, usually made of plastic, and were to be secured on the backside of one’s head with the help of strings or elastic bands.

The honey collectors’ masks were among one of the many ways in which the government tried to control human- tiger conflict. Some other methods were placing electric dummies on the forest fringes, which when the tiger attacks, receives a jolt of electrocution. There were also efforts taken by the government to dig freshwater ponds inside the forest because it was believed that the Sundarban tigers are man- eaters because they drink the saline water of the rivers, which disrupts the animal’s normal consumption behaviour. Among all these efforts, the mask trial according to the government had been a success. Anthropologist Annu Jalais recollects her encounter with these masks, and says that though the government saw it as a successful way to minimise human- tiger conflicts, there remains certain fault lines. Jalais recounts that during one of her visits to the Sundarban, while forest officials took pride in explaining how these masks are extremely effective, they did not allow her to wear one and enter the forest without other levels of protection. Her study hints at the differential way the state treated her (as belonging from the upper class), and how it treated the lives of the marginalised islanders.

In present day Sundarban, these plastic masks can be found with many honey collectors’. Though not as life saving equipments, they are preserved as relics. Some islanders talk about how useless these masks are in reality, and how many lives have been lost because mask wearers got over confident in the forest, and ignored their usual safe keeping mechanisms. Unlike the popular idea of a grassy or mossy forest floor, the Sundarban forest floor is extremely difficult to walk on. Most areas are swampy with the sharp protruding roots of the mangrove trees all around, and many honey collectors also recounted that maintaining the mask on their heads added to the already difficult experience.

Also is interesting to see the type of masks employed for this case. Some villages are in possession of a typical Salvatore Dali mask, complete with its white look, and the archetypal moustache and the big eyes. Some masks worn were also toy masks, resembling the face of a joker, or a teddy bear. Do you think the tiger should have recognised Dali or a Joker or a Teddy Bear and avoided preying on the human, who according to it is food? What do you think about face masks we are wearing in present day to shield ourselves from the Covid- 19 virus? Around us, there are many people who wear their Covid- masks below their nose; some wear it on their chin, while some keep it in their pockets. According to them, is the virus to shy away from making them a host because of just the sight of the mask on their faces? Maybe the same logic as the tiger avoiding Salvadore Dali in the forest applies here. Write to us about what you think about it!

References:

Jalais, Annu. (2008). Unmasking the Cosmopolitan Tiger. Nature and Culture, 3(1). pp. 25- 40.

Mallick, Jayanta. (2011). Status of the Mammal Fauna in Sundarban Tiger Reserve, West Bengal- India. Taprobanica, 3(2). pp. 52- 68.

Reza, Ahm. (2002). Man- Tiger Interaction in the Bangladesh Sundarban. Bangladesh Journal of Life Science, 14(1). pp. 5- 82.