PHOTOGRAPHY IN INDIA

Article By – Dixha Negi

Photography arrived in colonial India during the second half of the 19th century, soon after its very first invention. New photographic societies were being emerged, consisting of both Indian and British, amateurs and professional photographers. These people started documenting the people, architecture and landscapes around them, Photographic societies bloomed in and around the cities of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras.

By the 1870s, the commercial photography industry flourished, especially in cities like Bombay, capturing a range of subject matter. The photographers worked to meet the demand for photos as a means of souvenirs and postcards. Portrait photography also became increasingly popular, catering to people who wished to keep a portrait of their own or any other individual.

Many people have drawn connections between imperialism and the expansion of photography by the colonizers. As the National Archives UK puts it, “From its earliest development, photography was seen as a tool for documentation and control, particularly in ethnography – the systematic study of human cultures.” It was used as a tool to record and document the various cultures, traditions, people and environments that existed in British India. Many art historians have criticized the early colonist photography as being devoid of any humanization and individuality. The people in such photographs, are showcased as ‘ethnic’ and that being their only identity, thus reinforcing the stereotypes.

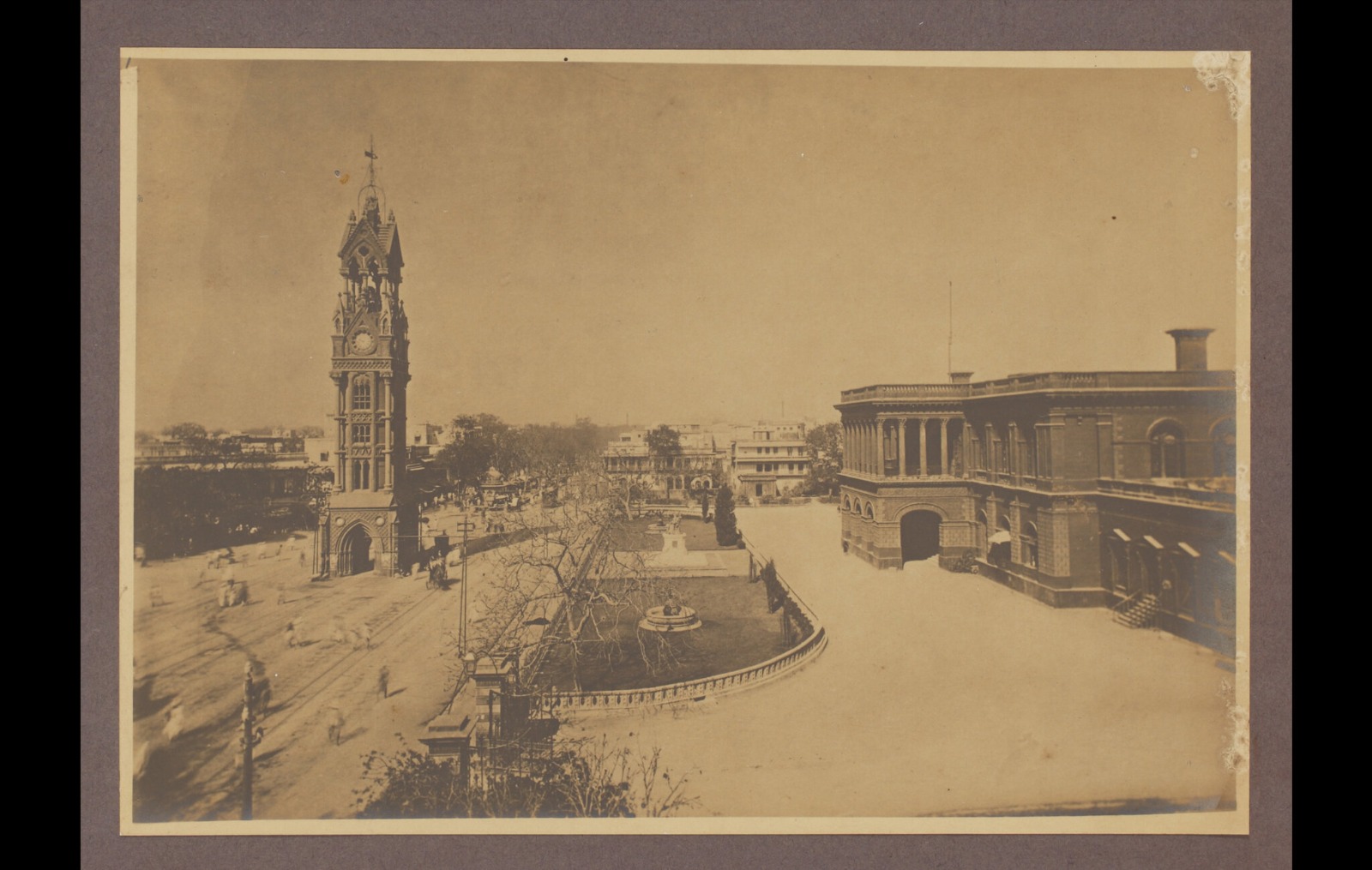

We know that the 19th century was a period of significant transformation in India, marked by political upheaval and technological advancements. The 1857 Sepoy Rebellion was a moment of major uprising against British colonial rule, which had a profound impact on the Lucknow region. The simultaneous rise of photography during this era provided a unique opportunity to document the aftermath of the rebellion and capture the city’s changing landscape, offering a valuable glimpse into the city’s past. These photographs provided a visual narrative of the sheer resilience and destruction caused by the rebellion. Such photographs were also a means to preserve our pre-colonial identities, by showcasing the cultural and architectural heritage.

AHMED ALI KHAN: THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Ahmed Ali Khan, a name often overlooked in the annals of Indian history, stands as a testament to the power of photography to capture and preserve the essence of a bygone era. As one of the earliest photographers from Awadh, Khan’s work offers a unique glimpse into the rich heritage and tumultuous events of the 19th century.

Early Life and Career

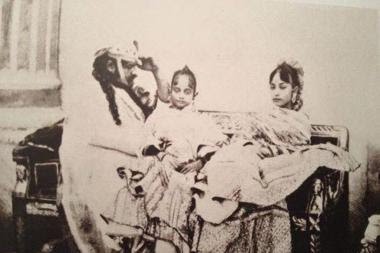

Ahmed Ali Khan also known by the alias Chote Miyan, because of his connections with the ruling Nawabs of that time, was hailed as the ‘first photographer’ from Awadh. Some scholars have traced his career from the 1850s to 1862. They believe that it was because of his encounter with a French tourist namely Baron Alexis de La Grange, who taught him basic photography skills, that Khan was able to explore this talent of his. Alexis Aimé Charles Louis de La Grange was a French politician, who is also known for his photographs of India between 1849-1851.

Ahmed Ali Khan enjoyed a degree of social and professional standing within the British colonial community. He was listed as a “Respectable Native Inhabitant” in the Bengal Directory of 1856. This recognition would have been important for a native photographer seeking to establish himself in a predominantly colonial environment. Khan sought appointment as the royal photographer through the prime minister of Awadh, Ali Naqi Khan, which granted him significant patronage and privilege. This gave him access to the Nawab’s court and the opportunity to photograph members of the royal family and other important figures.

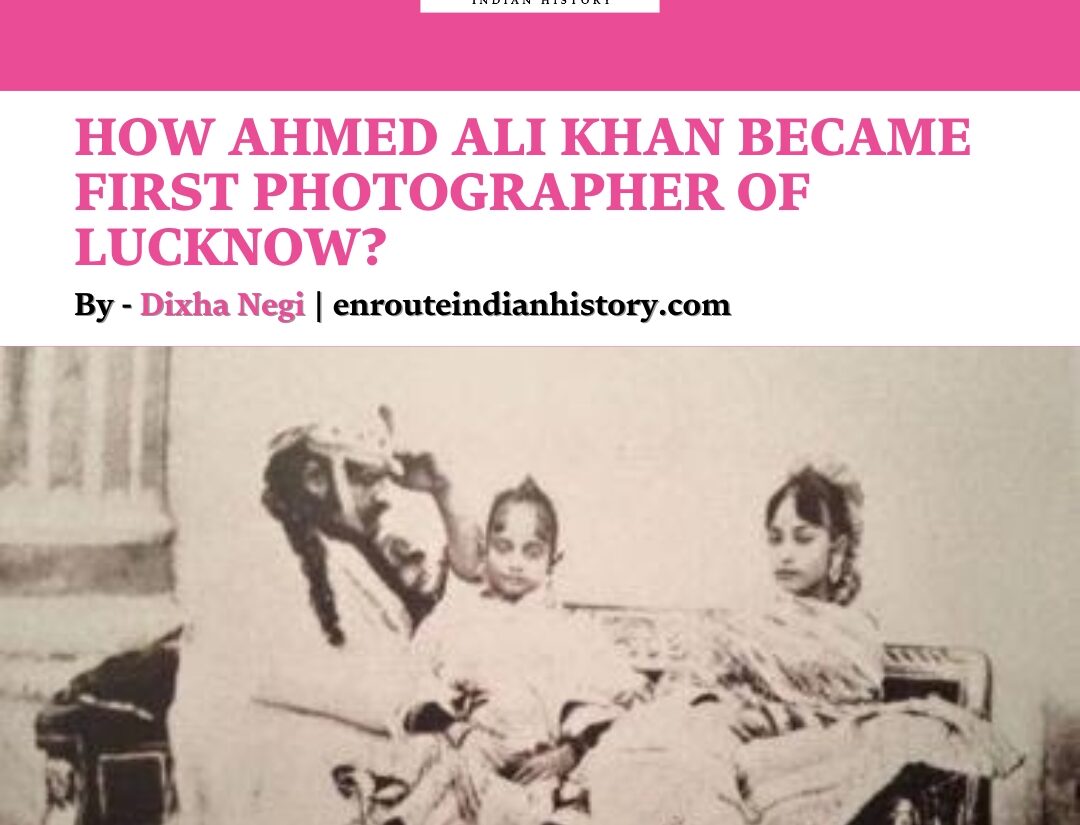

Ahmed Ali Khan was a remarkable figure who occupied a unique and influential position within the Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s court. Khan’s ability to enter the royal harem, a space typically restricted to women and eunuchs, demonstrates the high degree of trust and privilege he enjoyed within the court. His ability to direct the Nawab begums without offending Wajid Ali Shah hints at a certain degree of authority and respect within the court. This might have been due to him being one of the first and very few photographers and his expertise and ability to create flattering and aesthetically pleasing images.

Figure: Nawab Wajid A li Shah and his daughters (Credits: News18)

Figure: view of Lucknow, Baron Alexis de La Grange (Credits : Getty)

Cultural Exchange and Artistic Mastery

The fact that British officers and their ladies sought out Khan’s services highlights the cultural exchange and influence that were taking place between the British and Indian communities. His camera became a medium for these people to connect back with their families, showcasing a glimpse of their lives in India.

Khan’s mastery of daguerreotypes and photographic prints, coupled with his generous spirit to offer his services free of cost, hints at his deep passion for the art form. His proximity to the elite, combined with his popularity among Britishers, presents him as a man who navigated the intricate social landscape of colonial India. The 1857 Rebellion, saw Khan’s allegiance shift towards the rebels. He used photography to document crucial information for their cause. This act of defiance, if true, marked a stark contrast to his previous association with the British. It showcased his willingness to risk his privileged position to support a cause he believed in. Despite his involvement in the rebellion, Khan was later nominated to be a member of the Bengal Photographic Society. This reconciliation with the British authorities suggests a complex interplay of factors, including his artistic contributions, and his ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

Ahmad Ali Khan’s extensive photographic work, scattered across collections like the British Library, serves as a testament to his skill and the impact he made on the development of photography in India. His portraits, capturing the essence of individuals from various walks of life, provide valuable insights into the social and cultural landscape of the time.

AHMED ALI AND THE SONS

The British Library holds a vast collection of historical materials related to Awadh, including some documenting the last Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah. While there are portraits of the Nawab himself and his wives, a question arises about his sons and potential heirs.

Photographer Ahmad Ali Khan documented Wajid Ali Shah’s family extensively. His work included portraits of the Nawab’s second wife, Akhtar Mahal, and Nawab Raj Begum Sahibah. He even captured an informal group portrait with the Nawab, Akhtar Mahal, and their daughter. However, despite this comprehensive collection, photographs of Wajid Ali Shah’s sons remain elusive.

In 2018, the British Library acquired two fascinating portraits painted on ivory, believed to be of Wajid Ali Shah’s young sons. These predate the photographs by over a decade, dating back to around 1840. One portrait features a child of about a year old, supported by a bolster. The other shows a slightly older child, around two years old, seated in a European chair. An inscription on the frame suggests these portraits are of the last Nawab of Awadh’s children. It further suggests they came from a descendant whose ancestor sought refuge in Baghdad after, possibly the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny.

While the identity of the children in the ivory portraits remains unconfirmed, they offer a potential glimpse into the Nawab’s family and provide valuable historical context.

Figure 1: Portraits of the two young sons of Wajid Ali Shah, the King of Awadh by an unknown, British Library ( Credits: Photographed by Patricia Tena, 2019)

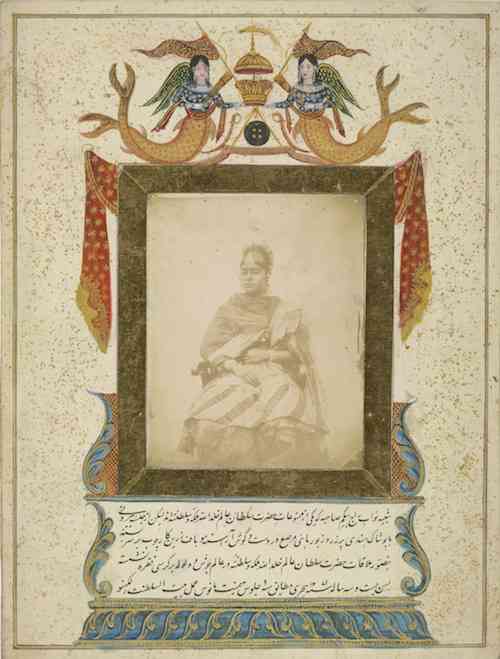

Figure: Picture of Nawab Raj Begum Sahibah, one of the concubines of the Sultan, aged 23 years. photographed by Ahmad Ali Khan, dated 1855. Credit: British Library (Public Domain)

AHMED ALI KHAN: AN ARCHITECTURE

Qaiserbagh, stands as a testament to the grandeur and opulence of Lucknow’s Nawabi era. The opulent palace complex built by Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Awadh, was a massive undertaking, constructed between 1848 and 1852, reportedly costing a staggering 80,000 pounds.

The architect behind this architectural marvel was Ahmad Ali Khan also known as Chhotey Mian. An amateur photographer and a figure of significant influence in Lucknow’s cultural scene, Khan is believed to have also designed the Hussainabad Imambara, another iconic landmark in the city.

Qaiserbagh was a sprawling complex, featuring ten imposing gateways. Two of these, known as the Lakhi Darwaza, have survived the ravages of time and remain standing today. The palace was renowned for its intricate architecture, lush gardens, and luxurious interiors, reflecting the Nawab’s lavish lifestyle and artistic sensibilities.

Figure : Panorama of Lucknow, Taken from the Qaiserbagh Palace (Credits: Google Cultural Centre)

Ahmed Ali Khan, a not-so-forgotten figure in Indian history, emerges as a pioneer in photography. His work, spanning the tumultuous 19th century, offers a unique glimpse into the rich heritage of Awadh. Khan’s ability to capture the essence of a bygone era through his lens is a testament to his skill and passion. His portraits of the Nawab’s family, the royal court, and the broader social landscape of Awadh provide invaluable historical insights.

Beyond his photographic contributions, Khan’s role as an architect and his involvement in the 1857 Rebellion reveals the multifaceted nature of his life. His story is a reminder of the power of photography to preserve history, document cultural heritage, and even challenge the status quo.

REFRENCES AND IMAGES

Blogs.bl.uk. (2020). Asian and African studies blog: Photography. [online] Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/photography/page/2/ [Accessed 22 Sep. 2024].

Roy, M. (2020). In an unknown artist’s miniatures, we get a glimpse of the heirs apparent of Awadh’s last king. [online] Scroll.in. Available at: https://scroll.in/article/961623/in-an-unknown-artists-miniatures-we-get-a-glimpse-of-the-heirs-apparent-of-awadhs-last-king [Accessed 22 Sep. 2024].

Early photography in India: Tracing photographers through copyright records – The National Archives blog

Times Of India (2023). Why was Nawab’s palace complex called Qaiserbagh? [online] The Times of India. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/lucknow/why-was-nawabs-palace-complex-called-qaiserbagh/articleshow/100398499.cms [Accessed 22 Sep. 2024].

Sharda, S. (2014). Avadh’s first photographer fought against the British in 1857. [online] The Times of India. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/avadhs-first-photographer-fought-against-the-british-in-1857/articleshow/40727137.cms [Accessed 22 Sep. 2024].

- September 27, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read

- March 27, 2024

- 10 Min Read

- March 27, 2024

- 11 Min Read