In the heart of Mughal India, where history and culture converged in a kaleidoscope of artistic brilliance, the celebration of Christmas took on a unique and enchanting form. The unique celebration of Christmas unfolded in this dynamic and diverse setting. And this celebration is artistically portrayed by the skilled hands of Mughal painters and depicts the enchanting ways in which Christmas was embraced. The Mughal era, characterised by a vibrant amalgamation of diverse influences, witnessed the integration of Western traditions into the elaborate tapestry of festivities. Against the backdrop of opulent courts and bustling bazaars, Mughal artists emerged as storytellers, capturing the spirit of Christmas with remarkable finesse. These masterful artists, adept in their craft, translated the essence of Christmas celebrations onto canvas, offering a visual feast that transcends time.

While the Nativity play finds its roots in medieval Europe, its presence in North India can be traced back to the era of Akbar the Great. During his reign, Akbar extended an invitation to the Jesuit fathers, marking the introduction of the Nativity play to his court in Agra.

In 1579, the invitation extended by Mughal Emperor Akbar to Portuguese Jesuits from Goa brought them great joy. Their aspiration to convert Akbar to Christianity represented a significant endeavour beyond the European realm. Responding to Akbar’s request, court artists were instructed to incorporate Christian imagery into his royal propaganda. However, despite this collaboration, Akbar stopped short of embracing Christianity himself.

Christian iconography displays remarkable adaptability. Upon the arrival of Jesuits in India, Christ underwent an “Indianization.” However, during the reigns of Akbar and Jehangir, particularly through the influence of four artists, there was a perceptible shift. These artists learned from and assimilated Western artistic styles, resulting in progressively more European portrayals of Christ and Mary.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio ; The Adoration of Magi, from a mirror of Holiness of Father Jerome Xavier dating back to 1602 – 4.

In this rendition of the Nativity scene, a familiar tableau in Christian traditions, Mary and Joseph introduce the infant Jesus to the three Magi. The Magi, in a symbolic gesture of reverence, have placed their crowns on the ground as a homage to the King of Kings. Notably, the three Magi are depicted wearing Portuguese costumes, serving as a visual cue for the Mughal audience to signify their foreign origin and belief in Christ.

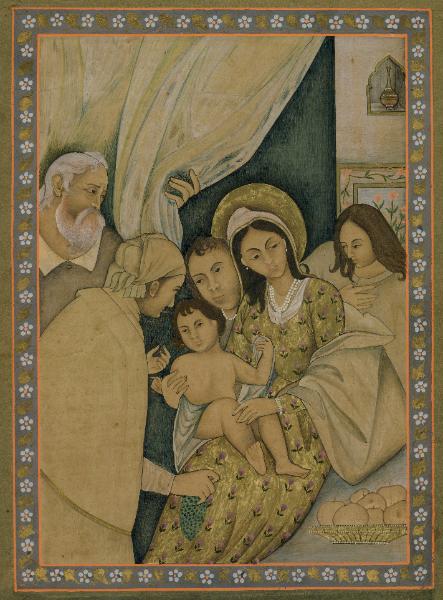

Michael Backman Ltd, London ; A miniature painting of Madonna and Child during the Mughal era dating back to the nineteenth century.

From the sixteenth century onward, Indian artists experienced a notable impact from European artistic styles and themes, particularly after a Portuguese Jesuit mission based in Goa gained permission to enter Emperor Akbar’s court in 1580. The missionaries brought along various images, likely engravings, depicting the Madonna and Child, sparking immediate interest among Mughal Court painters.

Badauni, a biographer of Akbar, recorded that Abu’l Fazl, the royal biographer, was assigned to engage with the mission and translate the Bible into Persian. Akbar, in his pursuit of knowledge, dispatched a mission to both Goa and Spain, resulting in the acquisition of a copy of the Bible.

This influx of influence introduced a diverse range of new subjects to Mughal artistry, sometimes executed in a distinctly European manner, while at other times, as exemplified in this instance, incorporating strong allusions to a more typically Indian style. In the depicted scene, the figure of Mary wears a traditional cloth mantle alongside a Mughal-patterned floral gold dress. The architectural background and perhaps the jewellery further showcase this harmonious merging of artistic styles.

Christmas During Jahangir’s Reign

Similar to his father, Jahangir (1569-1627 CE) harboured a profound fascination for Christianity and Christian iconography, an influence clearly discernible in the artworks produced during his reign. Jahangir, who had attended Christmas festivities in both Lahore and Agra during the reign of Akbar, demonstrated his keen interest in the Christian celebrations. An intriguing account recounts Jahangir’s participation in Christmas events, notably his symbolic act of carrying a Beeswax candle resembling a Bishop to the church.

As his reign progressed, Jahangir’s affinity for Christmas celebrations continued, culminating in a significant event during his last visit to Delhi in 1625-26. On this occasion, he received an invitation from the Armenian Christians, who then had two churches in Delhi (unfortunately later destroyed by Nadir Shah in 1739), to partake in their Christmas festivities. Historical records, specifically the Franciscan Annals, vividly describe the Emperor being showered with rose petals, and the churches hosting Christmas dramas and nativity scenes. The celebrations were not limited to the emperor alone; they also drew the attendance of numerous Rajput chieftains and Mughal officials. Such grand festivities inevitably attracted large crowds, prompting the deployment of imperial forces to maintain order.

Highlighting the amicable relations between the Mughal rulers and the Armenian Christians, historian R V Smith narrates an incident during Jahangir’s visit to Delhi in 1625-26. Khawaja Mortiniphus, an Armenian merchant, presented Jahangir with five bottles of Oporto wine. Impressed by this gesture, Jahangir reciprocated by gifting Khawaja Mortiniphus a precious diamond sourced from the Golconda mines. This incident stands as a testament to the cordial ties that both Akbar and Jahangir cultivated with the Armenian Christian community.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ; Mother and Child with a White Cat: Folio from a Jahangir Album, attributed to Manohar, ca. 1598.

Prince Salim, who later ascended to the throne as Jehangir, followed in his father Akbar’s footsteps. However, unlike Akbar, who endorsed depictions of Jesus and saints in secular, royal, and religious contexts with influences from European art, Jehangir appears to have been more particular, especially regarding the portrayal of saints, insisting on a more distinctly European approach.

Despite the emphasis on European aesthetics, the undertones of propaganda are unmistakable. One striking painting portrays Jehangir as the ruler of the world, seated atop an image of Christ holding a cross. Another pair of paintings featuring Jehangir depicts him holding images of his father Akbar and his spiritual mother, Mary, underscoring the strategic use of art for propagandistic purposes.

Chester Beatty Library, Dublin ; Mughal Emperor Jahangir with Jesus.

In the upper left corner above the image of Jesus, a Persian inscription reads, ‘Hail, O helper of the poor.’ This inscription is designed to encompass both Jesus and Jahangir, specifically portraying Jahangir in his role as the benevolent monarch dispensing justice, symbolically holding the world in his hands.

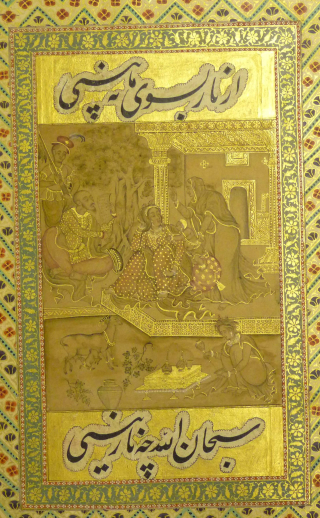

While there is a lack of documented paintings depicting Christmas celebrations at the Mughal court or individual illustrations in the Mirʼāt al-Quds, there exists a collection of drawings that serves as evidence of Mughal artists’ exploration with Christian iconography. This particular genre of painting gained popularity in the early seventeenth century, particularly during Jahangir’s reign. Mughal artists engaged in the appropriation of imagery from European engravings, drawing inspiration from these sources. Additionally, they received guidance from Jesuit priests, learning techniques on how to translate the cross-hatching from engravings into wash, a method utilised in the preparation of their nim-qalam drawings. This artistic experimentation marked a fascinating cross-cultural exchange between Mughal artists and European influences during this period.

British Library, London; Engraving of the Virgin and Child by a Dutch or Italian artist, 16th or 17th century in a Mughal album page, c. 1630.

British Library, London ; Virgin and Child with Anna the prophetess, Mughal school, c. 1605-10.

An example of the incorporation of an engraving depicting the Virgin and Child, which was affixed onto a Mughal album page. This album, curated specifically for Prince Dara Shikoh, featured various such engravings. Another illustration within the album showcases a nim-qalam drawing portraying the Virgin and Child accompanied by Anna the prophetess.

The intersection of Mughal art and Christian iconography stands as a testament to the dynamic cultural exchanges that unfolded during this fascinating period of history. While concrete depictions of Christmas celebrations within the Mughal court are notably absent from documented records, the experimentation with Christian imagery by Mughal artists reveals a captivating synthesis of Eastern and Western influences.

From the appropriation of European engravings to the utilisation of wash techniques guided by Jesuit priests, Mughal artists showcased their adaptability and artistic ingenuity. The albums curated for Prince Dara Shikoh, featuring engravings of the Virgin and Child, exemplify the tangible results of this cross-cultural exchange.

Jahangir’s reign, marked by paintings portraying him alongside Christian iconography, illustrates a deliberate fusion of Mughal imperial propaganda with European religious symbolism. These artistic endeavours not only mirror the personal interests of the Mughal rulers but also reflect broader themes of religious tolerance and curiosity about foreign cultures.

In unravelling the layers of Mughal artistry and its engagement with Christian iconography, we unveil a nuanced narrative of cultural curiosity, artistic experimentation, and the fluidity with which traditions were exchanged and integrated. This exploration serves as a poignant reminder of the rich tapestry woven by diverse civilizations, where artistic expressions become echoes of a bygone era, resonating with the harmonious coexistence of cultures in the vibrant mosaic of Mughal India.

References

- “How Akbar And Jahangir Celebrated Christmas.” 2019. Outlook India. https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/opinion-how-akbar-and-jehangir-celebrated-christmas/344594.

- Chari, Mridula. 2014. “Astonishing Christmas-themed Mughal miniatures from the courts of Akbar and Jehangir.” Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/697185/astonishing-christmas-themed-mughal-miniatures-from-the-courts-of-akbar-and-jehangir.

- Roy, Malini, and Ursula Sims. 2018. “Christmas at Lahore, 1597 – Asian and African studies blog.” Blogs. https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2018/12/christmas-at-lahore-1597.html.

- Losty, Jeremiah P., and Malini Roy. Mughal India: Art, culture and empire: Manuscripts and paintings in the British library. London: British Library, 2012.

- September 27, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- September 12, 2024

- 12 Min Read

- December 20, 2023

- 10 Min Read