Beginning with human culture, mother goddess worship has existed. Before the gods attained primacy, ancient cultures worshipped female goddesses for fertility and protection. The Paleolithic ‘Venus figurines’ found in Europe were early examples of this kind of tradition. Besides ancient cultures, mother goddess worship is also longstanding in India. Explorations in Baghor, Madhya Pradesh, uncovered a 9000–8000 BCE probable Upper Paleolithic sanctuary with a circular base and a multi-layered natural stone object. The Kol and Baiga tribes of the Kaimur highlands worship triangular stones as celestial creatures, demonstrating indigenous culture’s longstanding devotion to mother goddesses. From the beginnings of the Neolithic, fertility and reproduction became major goals. Spiritual rites required female figurines with fertility symbols to honor the feminine deity. However, the abundance and variety of these female forms can be seen in the efflorescence of Yakshis and different forms of goddesses, especially from the fourth century BCE, showing that goddess worship has long been important in India. By the time Tantric cults emerged in the early medieval period, goddess worship had permeated across Indian society and culture.

Delhi’s Contemporary Shrines: The Architecture and Its Recent Roots

The contemporary temples of Yogmaya and Kalkaji, whose antiquity is debatable, demonstrate that Delhi also has a deep connection with the worship of the divine feminine.

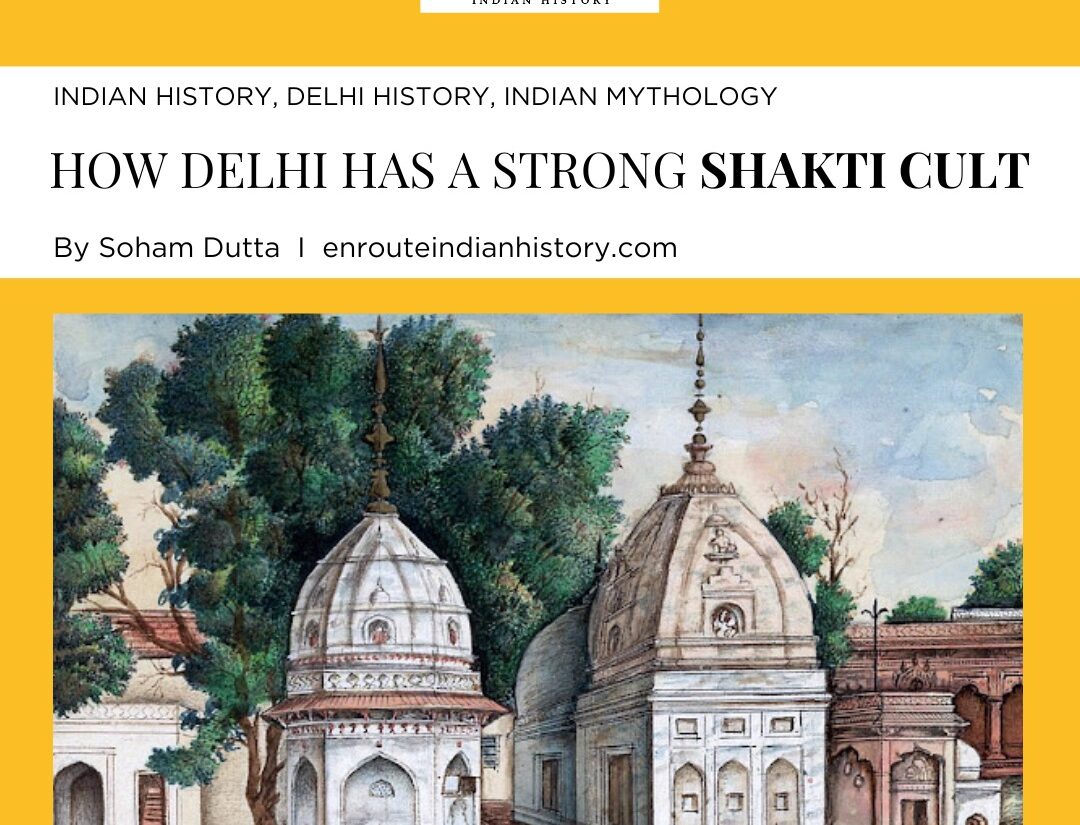

(Yogmaya Temple, Delhi – Ink and Colorson paper, ‘Reminiscences of Imperial Delhi’ 1843 )

The modern Yogmaya temple has an entry hall and a 17-foot-square sanctuary with a truncated shikhara tower and dome. The idol is coated in sequins and fabric and put in a marble well, with two miniature punkahs dangling above it. The walled enclosure is 400 feet square, with towers at each corner. The floor was originally red stone but has been rebuilt with marble (Smith,2005).

The Kalkaji temple complex is located on a hill in Kailash Colony. It is close to the Lotus Temple and Ashoka’s edict from the third century BCE. The Marathas first erected the edifice in 1764 CE, and Mirza Raja Kidar Nath, Akbar II’s Peshkar, enlarged it in 1816 CE. During the second half of the twentieth century, Hindu bankers and businesspeople in Delhi established multiple Dharamshalas around the temple. A pyramidal tower and a central room with 36 arched arches are features of the brick-masonry temple complex. A verandah surrounding the central room has two red sandstone tigers and a stone statue of Kali Devi carved in Hindi. The pedestal and railings also include Nastaʿlīq inscriptions (Stephan, 2002).

(Kalkaji Temple during early 20th Century CE, Architecture Research Quarterly, c.1905)

Tracing Their Antiquity: A Quest for Artifactual Evidence

Scholars like Upiender Singh and D.C. Sircar have cautiously speculated about the early historic existence of these shrines. Regardless, the antiquity of these shrines is uncertain because no solid evidence of a pre-existing shrine has been found. The Palam Baoli inscription from 1276 CE, which refers to the settlement as “Yoginipura,” suggests that the early medieval settlement in the Mehraulli area may have been associated with a Yogini temple that no longer exists, despite the lack of evidence for an ancient shrine at the current location of Yogmaya Temple. Another significant link can be seen at Ram Talab, also known as Guru Gorakhnath Temple, which is located near Sanjay Van Park. This temple has a historical background dating back to the medieval era. The site has samadhis of Nath saints as well as various sculptures.

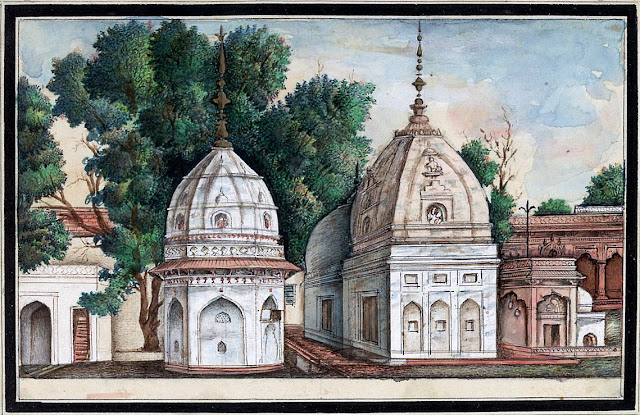

(Picture 1: Female sculpture possibly of a Yogini at Ram Talab,

Picture 2: A male sculpture possibly a form of Bhairava at Ram Talab; Mythic Society, 2023)

However, the most intriguing discoveries at this complex were two early medieval sculptures known as Devi/Mata and Bhairava Baba by locals (Keshari, 2023). Susan Huntington assigned these sculptures a period of approximately the 8th–9th centuries CE based on their iconography. The female sculpture, in a yogic posture, appears to be in a Lalitasana position with a club and disc. Her body is fleshy and rounded, and she features soft facial features. Her ornamentation is simple, with a kundala in both ears and with hairs in jatajuta (matted hairs) style, adding to her yogic qualities. The second sculpture, largely intact, features a slender male figurine with two hands, one in Abhay mudra and the other holding a bowl. It appears to be flying, with unclear facial features, jewelry, kundals, and a serpent’s hood behind his head. Based on its iconography and within the context of Yogini sculpture, it can be identified as a Bhairava sculpture. In the case of Kalkaji, any early historic or early medieval remains, whether in the present complex or its surroundings, are rather negligible. The lack of significant early historic or early medieval remains at Kalkaji suggests that the site may not have antique origins. However, further archaeological investigations in the area could provide more insights into its historical significance.

Kalkaji and Yogmaya in Popular Culture: Myths and Legends

In contrast to the few and scarce objects and physical remnants found elsewhere, these locations are associated with a variety of popular tales and living traditions. Local tales hold that Bhagwati Yogmaya, also known as Jogmaya, is an incarnation of the goddess Durga and Lord Krishna’s sister. She was born to Yashodha, whom Vasudeva brought back after leaving Krishna behind. Yogamaya escaped Kansa’s grasp and became trapped on a hill near Delhi, leaving behind her pindi, which is revered at the Yogamaya Temple. One of the five remaining Mahabharata temples and the only one from the pre-sultanate era is the temple, which the Pandavas built after the battle (Safvi 2015). Yogmaya’s birthday is Janmashtami, and the temple celebrates with a variety of events, including the Kalki Devi Janmohatsav and the Khatri’s Kuldevi festival. The most notable event is the ‘Phoolwalon ki Sair’, which began in 1812 CE, under the reign of Mughal Emperor Akbar Shah II. Anjuman Sair-e-Gul-Faroshan, a civil society organization, now organizes the event. The seven-day celebration attempts to foster communal peace between Hindus and Muslims.

{Picture 1: Sanctum of Yogmaya Temple},

{Picture 2: Worship of an ancient Linga and cultic object in Yogmaya temple complex; Project Mehrauli, 2023}

(Sanctum of Kalkaji Temple, Government of Delhi-SE District Portal, 2020)

In the case of Kalkaji, local traditions hold that two demons caused problems for the gods near Kalkaji Mandir. Lord Brahma requested assistance from Goddess Parvati, who revealed Kaushiki Devi, the lady in the jail. Kaushiki Devi battled the demons, but their blood dripped on the dry soil, prompting many more to appear. After observing the demon army, Kaushiki Devi knitted her brows, and Goddess Kali appeared from her brow. Kali slaughtered the demons and drank their blood, delighting the deities, and asked that she stay in the same spot. Locals also think Pandavas and Lord Krishna visited this place during that period. Despite being associated with ancient antiquity, the mandir gained prominence in the twentieth century with the creation of the new imperial capital of Delhi in the 1920s, and the city saw an exponential boom during World War II and partition (Sutton, 2022).

Final Thoughts: Making Sense of Popular Worship of Mother Goddesses

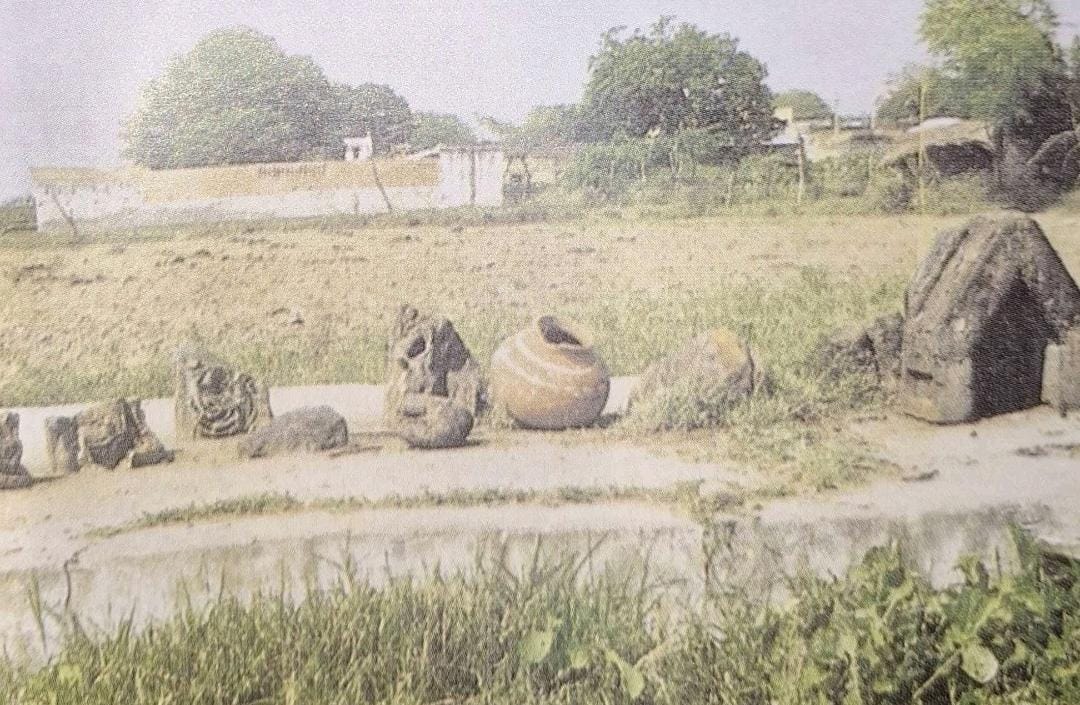

The worship of the mother goddess in Delhi and its surrounding areas has persisted for various practical and spiritual purposes. In their gramasthanas, or village shrines, which are frequently called Mata shrines, the villagers of several villages, including Tilpat, which is near Delhi, have collected antique sculptures to show how popular religious practices differ from literary religion (Singh, 2006). Another distinct rural practice in northern Delhi is the Sili Sat ritual, which is performed in honor of Shitala Devi, the goddess of illness, particularly smallpox (Freed and Freed, 1962).

(Village Shrine at Tilpat, 2006; picture by Upinder Singh)

These village traditions emphasize the variety and diversity of religious activities, blending ideas and customs into worship. As a result, these traditions, along with the well-known shrines of Kalkaji and Yogmaya, show how popular goddess worship was among both elites and common people. As a result, different people in different parts of the world and at different times have interpreted the mother goddess in different ways, reflecting ideas about feminity, independence, and power (Ganesh, 1990). She portrays a worldview in which femininity, as a creative force, is central, acting as a go-between for life and death and representing the hope of rebirth.

References

- Delhi: Ancient History of India, Social Science Press, 2006.

- Sutton, Deborah. (2022). Sacred architectures as monuments: a study of the Kalkaji Mandir, Delhi. Architectural Research Quarterly, 26: 47–56. 10.1017/S1359135522000380.

- Kamala Ganesh, “Mother Who Is Not a Mother: In Search of the Great Indian Goddess,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 25, no. 42/43, 1990, pp. WS58–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4396893. Accessed 1 Feb. 2024.

- Safvi, Rana. Where Stones Speak: Historical Trails in Mehrauli, the First City of Delhi. India, Element, 2015.

- Smith, Ronald Vivian. The Delhi that No-one Knows. India, DC Publishers, 2005.

- Keshari, Mihir. “The Yogini of the Yoginipura: A Note About Two Unreported Early-Medieval Sculptures From Delhi.” Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, vol. Vol 114, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.58844/GIZH7976.

- Freed, Ruth S., and Stanley A. Freed. “Two Mother Goddess Ceremonies of Delhi State in the Great and Little Traditions.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, vol. 18, no. 3, 1962, pp. 246–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3628878. Accessed 1 Feb. 2024.

- Stephen, Carr. The Archaeology and Monumental Remains of Delhi. India, Aryan Books International, 2002.