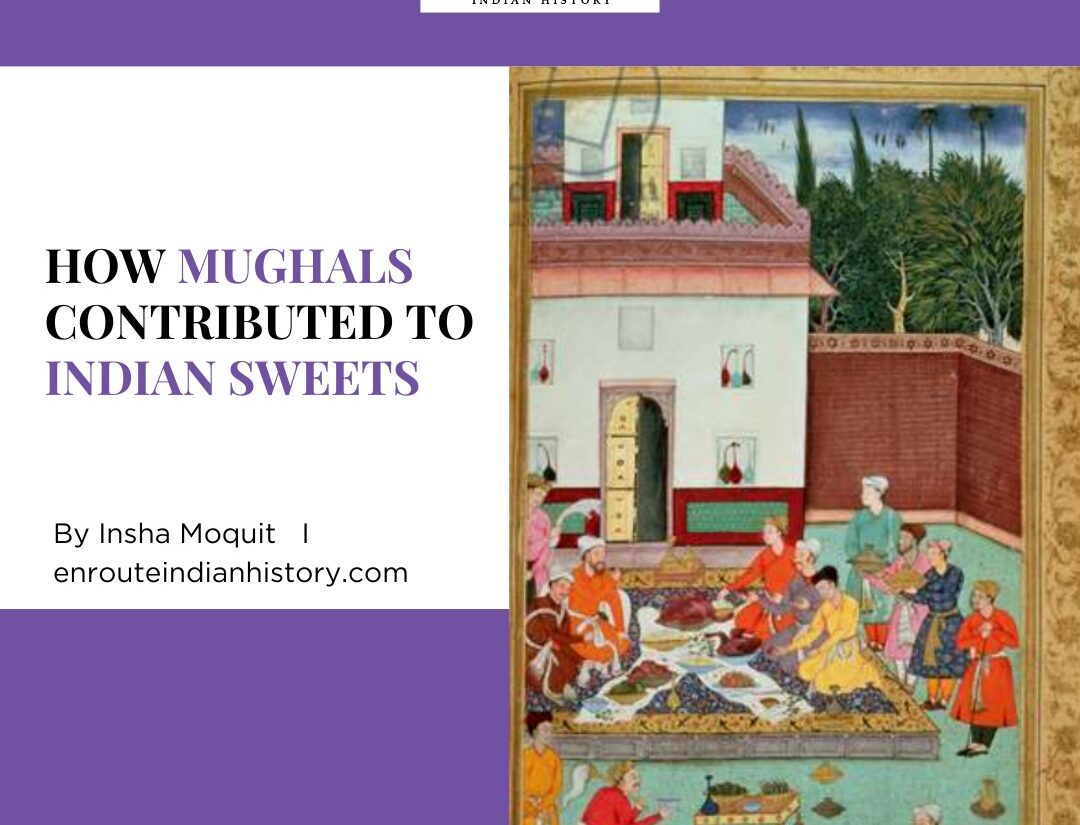

The Mughal Empire, which formerly ruled the Indian subcontinent, exemplifies the confluence of civilizations, splendor, and lasting legacy. This legacy also extends to the sweet and savory culinary traditions in the Indian kitchen. The royals have traditionally taken an incredibly delectable array of foods. The Mughals emphasized this aspect as well. During Akbar’s reign, the Mughal imperial kitchen evolved into a center for Mughal culinary invention and exploration, with trained cooks (khansamas) creating intricate delicacies that delighted the refined palates of emperors and nobles. Abul Fazl addressed this in his book Ain-i-Akbari.He opens by saying that,“His Majesty (Akbar) even extends his attention to this department, and has given many wise regulation for it; nor can be a reason be given why he should not do so, as the equilibrium of man’s nature, the strength of the body, the capability of receiving external and internal blessings, and the acquisition of worldly and religious advantages, depend ultimately on proper care being shown for appropriate food. This knowledge distinguished man from beast, with whom, as far as mere eating is concerned; he stands upon the same level.”

Mughal cuisine was a combination of Central Asian, Persian, and Indian culinary traditions, reflecting the empire’s cosmopolitanism. The Mughal courts’ royal kitchens (bazars) served elaborate feasts made by experienced cooks with aromatic spices, succulent meats, and exotic ingredients . Aside from their enduring legacy of Biryani, Haleem, Seekh Kebab, dum pukht pulao, and tandoors, the Mugals also feasted on a rich and luxurious array of delectable sweet delicacies.

Ibn-e-Batutta mentions the existence of ‘luqaimat-al-qadi.’ In Arabic, luqaimat means “small bites,” and that’s just what they are: little bites of sweetness. As soon as one bites through the sweet and crunchy crust, they can taste the subtle flavors of saffron and cardamom in the soft yet airy inside.The royal banquet also served ‘mitrani’, a sweet bread prepared with flour, sugar, ghee, and dry fruits. The Mughal royal kitchen also specialized in creating a variety of Halwa and Seviyan. Other popular sweet treats were firni, Shahi tukda, gulab jamun, and jalebi. These treats were created using milk, sugar, flour, nuts, and spices like cardamom and saffron.

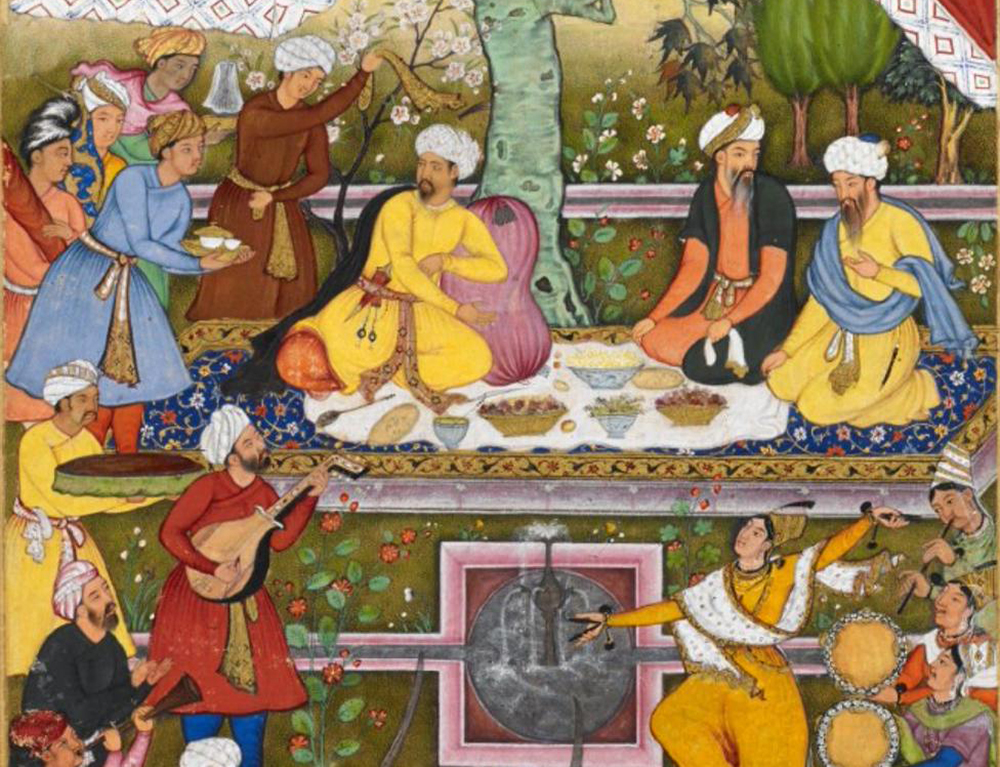

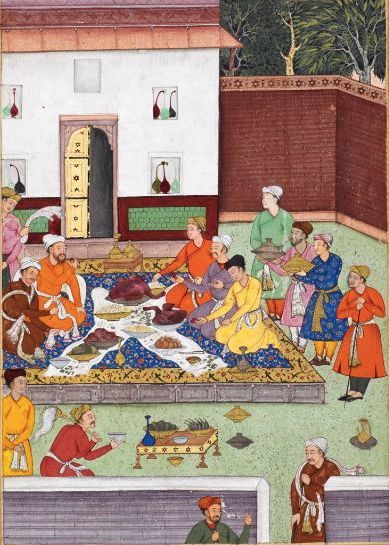

(A Mughal Feast, source: nationalarchives.nic.in)

Shahi Tukda: The Royal Morsel

Desserts prepared by Mughal Khansamas were distinguished by their rich, creamy textures, extensive use of nuts and dried fruits, and delicate application of aromatics such as saffron, cardamom, and rose water. One such classic dessert is Shahi Tukda, which literally means “royal piece.” Bread slices are deep-fried in ghee (clarified butter), then soaked in sugar syrup before being covered with a thick, creamy rabri (reduced milk) and nut garnish.

According to legend, Shahi Tukda was invented to use up leftover bread in royal kitchens. To avoid wasting food, the chefs converted stale bread into a sumptuous dessert worthy of the emperor. This narrative, whether genuine or not, demonstrates Mughal cooks’ imagination and ability to transform modest ingredients into something remarkable.

(Shahi Tukda, source: Google Photos)

Sheer Khurma: The Festive Delight

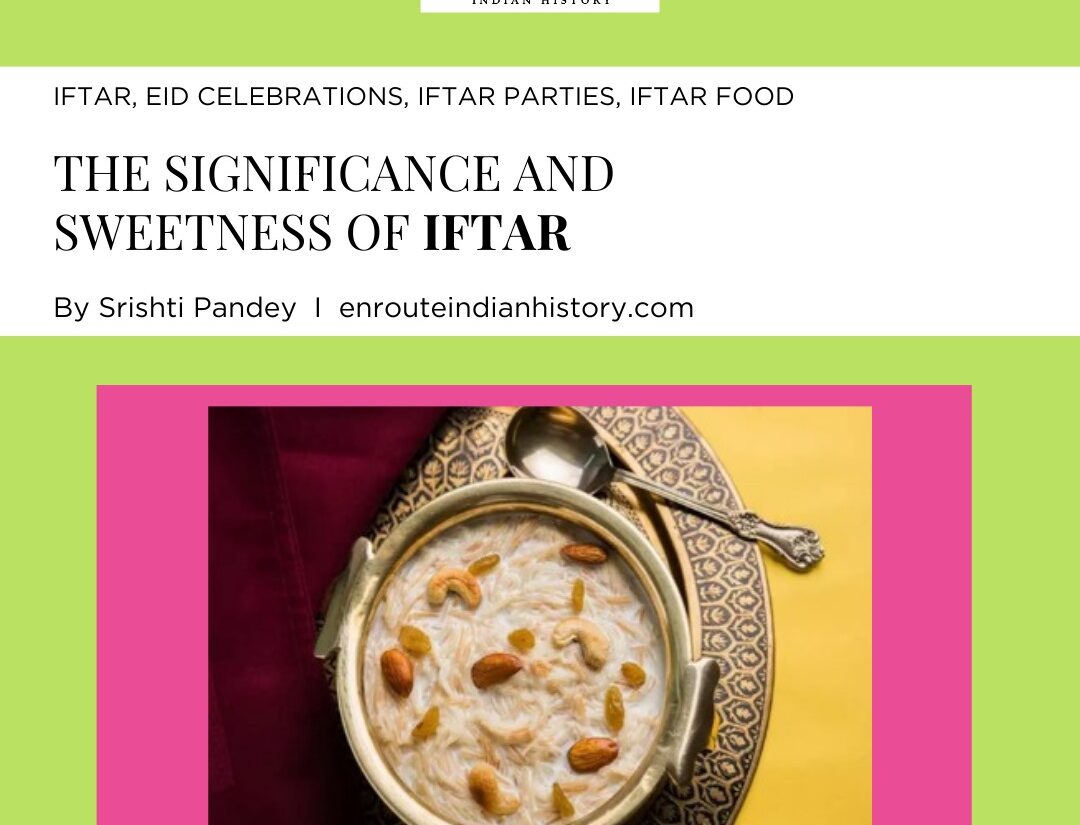

Another popular Mughal dessert is Sheer Khurma, which means “milk with dates” in Persian. This vermicelli pudding, often served during Eid celebrations, elegantly exemplifies the blending of Central Asian and Indian culinary traditions. Emperor Akbar is reputed to have been particularly fond of Sheer Khurma. According to Ain-i-Akbari, he once requested his chefs to create a dessert for Eid celebration that would symbolize the oneness of his diverse kingdom.

The result was Sheer Khurma, a blend of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian components that reflected the Mughal court’s eclectic background.

(Sheer Khurma, source: Google Photos)

Badam Firni: The Almond Delight

Badam Firni, a silky rice pudding with ground almonds, was another popular dish among the royal cooks. Emperor Jahangir, famed for his appreciation of exquisite cuisine and wine, was reported to have a particular affection for Badam Firni. According to court chroniclers, he once presented a chef with gold coins for preparing a particularly fine rendition of this delicacy, flavored with rosewater and topped with edible silver leaf.

(Badam Phirni, source: Wikimedia Commons)

Seviyan: The Versatile Sweet

Seviyan, or vermicelli-based sweets, were highly regarded in the Mughal Royal kitchen. These desserts, ranging from the simple Seviyan Kheer to the more sophisticated Zarda Seviyan, mentioned as Zard Birinj in Ain-i-Akbari was made with. 10 s. of rice; 5 s. of sugarcandy; 3½ s. of ghee; raisins, almonds, and pistachios, ½ s. of each; ¼ s. of salt; 1/8 s. of fresh ginger; 1½ dáms saffron, 2½ misqáls of cinnamon, which showed off the diversity of this humble ingredient. A beautiful narrative from Emperor Shah Jahan’s court speaks of a competition between royal chefs to make the most innovative Seviyan meal. The winning dish was a combination of vermicelli, condensed milk, saffron, and pistachios designed to replicate the delicate marble inlay work of the Taj Mahal, which was under construction at the time.

(Seviyan, source: Google Photos)

Khubani Ka Meetha: The Apricot Ambrosia

While not a Mughal innovation, Khubani Ka Meetha (sweet apricot dessert) rose to prominence during the later Mughal Empire, particularly in the Deccan region. This dessert is reported to have been a favorite of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor banished to Rangoon by the British. In his exile poems, he frequently reminisced about the flavors of his lost realm, notably the sweet tanginess of Khubani Ka Meetha.

(Khubani ka meetha, source: Wikicommons)

Luxurious Ingredients and Culinary Alchemy of Mughal Sweets

The Mughal rulers’ enormous territory allowed them access to a diverse range of ingredients, both indigenous and imported. Milk and milk products were the base of many Mughal sweets, typically reduced to make rabri or khoya, which added richness and creaminess to desserts. Nuts like almonds, pistachios, and cashews were freely utilized as food and decorations, providing texture and flavor. Dried fruits like dates, apricots, and raisins were valued for their natural sweetness and chewiness. Saffron, cardamom, and rosewater were vital for infusing delicate flavors and scents into sweets. Ghee was used to sauté and give flavor to sweets. Sugar was the predominant sweetener, but honey was also used in some desserts. Many puddings and sweet breads were made with grains such as rice and wheat (either flour or vermicelli).

Many milk-based sweets needed hours of slow simmering to attain the desired consistency and flavor depth. Desserts such as Shahi Tukda required precise layering of various components for both flavor and visual appeal. The practice of gently evaporating milk to produce thickened milk solids (khoya) was essential for many desserts. The proper use of aromatics was an art form in and of itself, with chefs painstakingly harmonizing flavors to create harmonious taste profiles. The final presentation was as essential as the flavor, with exquisite garnishes of almonds, silver leaf, and flower petals.

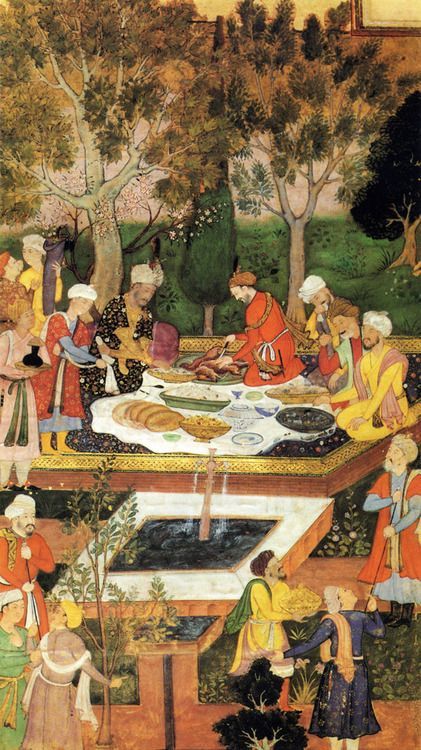

(The Mughals celebrating Nauroz with sweets and seviyan, source: Digital Library of India)

Sweet Tales From The Past : The Mughal Dessert Legacy

The Mughal monarchs’ fondness for sweets is well documented in historical records and court chronicles. While not strictly a dessert, Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, was known for his fondness of melons and frequently imported them from Central Asia. Emperor Akbar, famed for his curiosity, reportedly asked his chefs to make a dessert out of exclusively white ingredients, which resulted in milk pudding flavored with white cardamom and adorned with slivered almonds. According to the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, Jahangir had special gardens built to supply his chefs with fresh produce all year round because he was so passionate about fruits and sweets. Aurangzeb, unlike his predecessors, was noted for his ascetic lifestyle, favoring simple pleasures such as plain rice pudding.

(A banquet including roast goose given to Babur by the Mirzas (1507), source: wikimedia commons)

These anecdotes not only illuminate the personalities of the Mughal kings but also demonstrate the essential role that food, particularly sweets, played in court life and diplomacy. Mughal desserts have had a profound and far-reaching influence on contemporary Indian cuisine. Many Mughal desserts have become staples of Indian cuisine, transcending regional and religious differences. Desserts like Sheer Khurma and Zarda are now synonymous with celebrations such as Eid, representing festivity and community. Mughal sweets’ precise preparation skills have influenced Indian dessert-making practices as well. The practice of blending milk, nuts, and aromatics remains a trademark of many Indian sweets.

From the opulent imperial Bawarchi Khana of bygone eras to the busy streets and homes of contemporary India, these desserts have seen a transformation through time, all the while maintaining their fundamental essence. Today, when we bite into a piece of Shahi Tukda or a spoonful of aromatic Badam Firni, we are celebrating a historical tradition as much as a dessert.

Mughal sweet delicacies serve as a link between the past and present in the always changing world of Indian cuisine, encouraging cooks and home cooks to experiment, invent, and produce. One delicious mouthful at a time, the tradition of the Mughal royal kitchen will endure as long as there are people who value the artistry of well-made sweets.

REFERENCES

- Achaya, K. T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford UP, 1994.

- Helou, Anissa. Feast: Food of the Islamic World. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

- O’Brien, Charmaine. The Penguin Food Guide to India. Penguin Books, 2013.

- Husain, Salma. The Mughal Feast: Recipes from the Kitchen of Emperor Shah Jahan. Roli Books, 2020.

- Bhatnagar, Sangeeta, and R. K. Saxena. Dastarkhwan-e-Awadh: The Cuisine of Awadh. HarperCollins Publishers India, 2004.

https://recipes.timesofindia.com/articles/features/10-best-mughlai-desserts/photostory/59051156.cms

https://curlytales.com/delectable-north-indian-sweets-that-comes-from-the-mughal-kitchens/