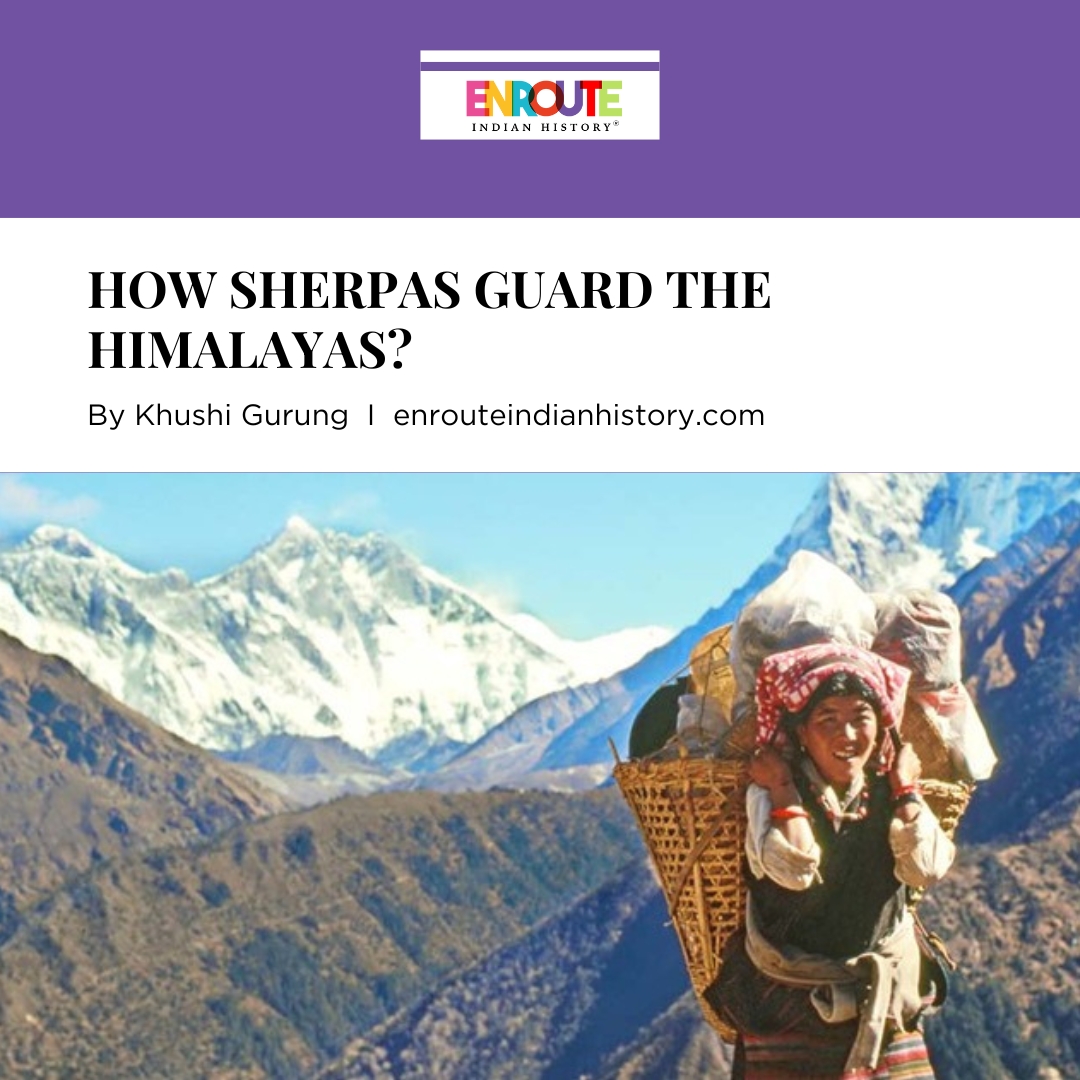

Source: American Himalayan Foundation, A sherpa woman carrying goods in ‘doko’, a kind of basket made from bamboo. They are hand-woven in a conical or “V” shape. Dokos are especially used by Sherpa porters to carry goods in northern Indian mountainous regions.

Towering over the northern boundaries of India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet, the Himalayas are the icy mountain range which are nearly 3000 km long, 250-350 km wide in range. Himalayas have been revered as a divine abode by various religious and ethnic groups, inspiring countless legends and drawing pilgrims, adventurers, and scholars alike. Nestled high in the heart of Asia, the Himalayas stand as a majestic testament to nature’s grandeur and indomitable spirit. Stretching across five countries—India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Pakistan—these towering peaks are not just the highest in the world but also the cradle of diverse cultures, rich histories, and unique ecosystems. Among the numerous communities that call these mountains home, the Sherpa people hold a special place in the annals of Himalayan lore. Renowned for their exceptional mountaineering skills, the Sherpas have lived in the shadow of these mighty peaks for centuries, thriving in one of the most challenging environments on Earth. Their resilience, courage, and deep spiritual connection to the mountains have made them indispensable to numerous expeditions aiming to conquer the world’s tallest summits, including the iconic Mount Everest. We will now delve into the fascinating world of the Himalayas and the Sherpa community, exploring their intertwined destinies, cultural heritage, and their contribution to mountaineering.

Their History and Migration

Source: Ace the Himalaya, Thame village, a peaceful settlement that once thrived on the ancient salt trade route between Tibet and Nepal.

Source: Karuna Dana, The Kham region (lower right corner) in Tibet from where the Sherpas are said to have migrated.

The Sherpa are an ethnic group from the most mountainous region of Nepal, high in the Himalayas. In Tibet shar means East and pa is a suffix meaning ‘people’, hence the word sharpa or Sherpa, meaning “people from the East.” The term “sherpa” is also used to refer to local people, typically men, employed as porters or guides for mountaineering expeditions in the Himalayas. They are highly regarded as experts in mountaineering and their local terrain, as well as having good physical endurance and resilience to high altitude conditions.

Sherpas have an ancient and rich historical background that is intertwined with several regions of Tibet and Nepal alike. Since ancient times, people have migrated from one place to another. Various push factors motivate people to leave their homeland, while pull factors attract people to new areas. According to some historians, the Sherpas are believed to have their roots in the Kham region of Eastern Tibet from where they originated. This is also why they got the name ‘Sherpa’ as it translates to ‘people from the east’. The Sherpas then migrated to eastern Nepal in search of better places to live, but according to some local sherpa people it is said that due to the religious conflicts of Mahayana Buddhism in Tibet and opening of new opportunities and pastures, these nomadic people first migrated towards the Solu-Khumbu region of Nepal as it was a crucial trade route between Nepal and Tibet and had many grazing grounds for herds after which they gradually moved westwards along salt trade routes. Since then, Sherpas living in the high Himalayan terrains of Nepal have preserved their own unique language, religion, architecture, systems of social organisation, economy, land-use practices, dress, and ornamentation. According to Sherpa oral history, four groups migrated from Kham in Tibet to Solukhumbu at different times, giving rise to the four fundamental Sherpa clans collectively called ‘ru’: Minyangpa, Thimmi, Lamasherwa, and Chawa. These four groups gradually split into the more than 20 different clans that exist today. Two of the four original or proto clans- Minyangpa and Thimmi first occupied the eastern and western parts of Khumbu and the remaining two proceeded to Solu region later followed by majority of the other clans. This migration is speculated to have taken place in between the 10th to 15th centuries AD. They were also looking for new lands for new work opportunities, which ultimately led them to the majestic gates of the Everest region. The Everest region was also in the early era of being a trade route from Nepal and Tibet, and there were more job opportunities like animal husbandry, guest houses, etc. After the migration, most of the Sherpas started to settle down in other regions of Nepal like Thame (which later became to known as the Sherpa village).

The Culture and Traditions

Source: The Partners Nepal, Traditional Sherpa people greeting

Source: WikiMedia Commons, The famous Tengboche Monastery (Tibetan Buddhist monastery) of the Sherpa community in winters.

The Sherpa community has a rich cultural heritage, as the culture of Tibetan Buddhism has been translated from generation to generation. Sherpas have special celebrations, traditional clothing, language, society, food, and a unique way of life. They are good at living in challenging places.

The language of the Sherpas, called Sherpa or Sherpali, which is a Tibetan dialect, and thus it is a part of the Tibeto-Burman Family of languages, to which many of the other languages of Nepal also belong. All Sherpas speak Nepali, the official language of Nepal. While there is no Sherpa writing system, many Sherpas are literate in Tibetan, Nepali, and in some cases Hindi and English as well. Religion plays a central role in Sherpa culture. Predominantly Tibetan Buddhists, their practices are influenced by the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, which emphasizes mysticism and the integration of indigenous Bon traditions. Monasteries, or gompas, are spiritual and community centres. The most famous is Tengboche Monastery, situated on a ridge with panoramic views of Everest and Ama Dablam. Mani stones, inscribed with prayers, and prayer flags fluttering in the wind are common sights, symbolizing blessings carried by the wind. Sherpa festivals are vibrant expressions of their spiritual and communal life. Losar, the Tibetan New Year, is the most significant festival, marked by feasting, dancing, and religious rituals. It usually falls in February or March and involves visiting monasteries, lighting butter lamps, and performing traditional dances like the Cham dance. Dumji is another major festival which celebrates the birth of Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava), the founder of Tibetan Buddhism. Sherpa are not picky or choosy with their food since there is a need for more options or availability of fresh produce. Some everyday dishes and the most common Sherpa food delicacies include Riki kur, which is a kind of Potato Pancake; Sherpa Noodle Soup, which is a kind of Thukpa; Sherpa butter tea; Dhindo, Gundruk, Sherpa or Tibetan bread, etc. Yak products are central to Sherpa cuisine, with yak butter and chhurpi being common. Chhurpi is a dry chewy snack that is consumed in variety of ways like snacking, cooking and in earlier times bartering.

Source: Linkedln, Sherpas and the yak.

Source: Linkedln, Preparation of Yak Cheese (chhurpi) from yak milk. The woman is seen separating solid mass from the milk which is then pressed, dried, and hardened, resulting in a durable, chewy cheese

Source: India Mart, Blocks of chhurpi.

Source: linkedln, Chhurpi sticks left to dry.

When it comes to livelihood in the mountain it is quite harsh and demanding. The Sherpa people use surrounding forests and grasslands for their survival ever since they first migrated into Khumbu from Tibet. Natural resources gathering, farming, and livestock, the Sherpa economy is directly related to their mountain environment and falls into distinct categories: field agriculture, animal husbandry, trade, and recent innovation tourism and mountaineering. Sherpas concentrate their efforts on animal husbandry, keeping Yaks and Naks and grazing them along the vast and grassy alpine slopes. Yaks and Naks are the main livestock which is adapted to high altitude as far as 5000m. This livestock is vital for the livelihood benefits as they provide milk, hair, fur, hides, and dung. Yaks and Naks provide wool, milk, and meat. Other than animal husbandry Yaks are also used for transportation and logistics. They are used to carry heavy loads of up to 100 kg, making them essential for trekking and mountaineering expeditions, where they transport equipment, food, and other supplies. Yaks can navigate the rugged, uneven terrain of the Himalayas more effectively than other animals or vehicles, which are often impractical in such conditions.

Source: Izbatr, Traditional Sherpa female dress. Notice the strip apron clothing.

Their traditional dress, which is made of sheep and yak wool, consists of a black or brown cloak for men and a dark, woollen dress with a striped apron for women. Both married and unmarried women wear the rear apron (Gyaptil or Matil), while the front apron (pangden) is worn only by married women. This is one way to know if the girl is married or not. In some cases, the quality, intricacy, and colours of the pangden can indicate the social status or wealth of the family. More elaborate designs might be associated with higher social standing. Sherpas place exceptional value on certain types of jewellery, for example, silver amulet boxes and necklaces with coral or turquoise and dzi stones. Trade is also the source of a number of very substantial fortunes. Sherpas like to make long trading expeditions, and men often go off on such journeys singly or in groups for many months, leaving both domestic chores and agricultural work in the hands of women. They traditionally traded items such as grains, cloth, and spices from the lowlands with Tibetan goods, including wool and yaks. They also facilitated the exchange of agricultural products and local crafts.

Sherpas and Mountaineering

Source: Mark Horrell, Scottish mountaineering doctor Alexander Kellas was the first person to recognise Sherpas’ great ability at high altitude

Over the years of migration, Sherpas have become synonymous with high-altitude mountaineering, earning global recognition for their unparalleled skills, resilience, and deep connection with the Himalayas. The Sherpas’ involvement in mountaineering dates back to the early 20th century when European climbers began exploring the Himalayan peaks. The first man to notice the Sherpas’ incredible ability in the mountains was a Scottish chemist and climber called Alexander Kellas.

Kellas made eight expeditions to the Himalayas between 1909 and 1921. He completed many first ascents of peaks over 6000m, and made the first ascent of 7128m Pauhunri in 1911 with two unknown Sherpas. At the time it was the highest mountain that had ever been climbed (keeping in mind that Mt Everest was still known to be the highest mountain but was not climbed by any human being in the beginning of the 20th century). This marked the beginning of British expeditions to Mount Everest during the British Raj in the 1920s and 1930s and the beginning of Sherpas’ crucial role in high-altitude expeditions. Their exceptional ability to acclimatize to high altitudes, coupled with their intimate knowledge of the treacherous terrain, made them invaluable assets to these early expeditions. Historically, Sherpas were traders and farmers, often traversing mountainous terrain for trade. This developed their strength and familiarity with the rugged landscape, laying the groundwork for their future roles as porters. The turning point came in the early 20th century with British expeditions aiming to summit Everest because during the early 20th century, the British Empire was at its peak, and there was intense national pride in achieving significant accomplishments. Climbing the world’s highest peak was seen as a way to demonstrate British strength, endurance, and superiority in exploration.

Source: National Geographic, Edmund Hillary (left) and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay reached the 29,035-foot summit of Everest on May 29, 1953, becoming the first people to stand atop the world’s highest mountain.

In the 1920s, British climbers recognized the Sherpas’ exceptional physical abilities and intimate knowledge of the Himalayas, hiring them as guides and porters during the Himalayan expeditions. One of the most iconic moments in mountaineering history is the first successful ascent of Mount Everest on May 29, 1953, by Sir Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa of immense repute. This historic achievement not only put Sherpas on the global map but also solidified their reputation as the backbone of Himalayan expeditions. Tenzing Norgay’s role was pivotal, highlighting the critical support Sherpas provide to climbers aiming for the world’s highest peaks. All this is because the Sherpas have a profound knowledge of the mountain terrain. They gained this knowledge from years of climbing expedition experience (as the Himalayas is their homeland), which is invaluable. Sherpa people live in the high-altitude regions of Nepal which makes them well adapted to the high altitudes. Recent studies and research have found out that Sherpa has a genetic advantage in high altitude and thus can adapt to the high altitude without more acclimatization. They are the ones with the understanding of the mountain’s ever-changing weather patterns and can sense sign indications of the catastrophe such as approaching avalanche, storm, and unexpected climate conditions. These adaptations are crucial for survival and performance in the extreme conditions of the Himalayas. Beyond their physical attributes, the Sherpas’ cultural and spiritual connection to the mountains plays a significant role in their mountaineering prowess.

“We Sherpa people have a great respect for that mountain. She is the mother God of the earth” says Lakhpa Sherpa, the first Nepali woman to climb Everest and descend Everest successfully, in the 2015 documentary film ‘Sherpa: Trouble on Everest’.

The Himalayas are considered sacred in Sherpa culture, home to deities and spirits. Mountaineering for Sherpas is not just a profession but a spiritual journey. They perform rituals and seek blessings before embarking on expeditions, believing that the mountains must be respected and revered.

In the 21st century, Sherpas continue to play a pivotal role in mountaineering, adapting to the evolving demands and challenges of the industry while maintaining their traditional expertise and values. The rise in global interest in climbing peaks like Mount Everest has increased the demand for Sherpa guides, who are crucial for the success and safety of these expeditions. In 2001, Temba Tsheri Sherpa became the youngest Everest climber in the world (holder of the Guinness World Record), then aged 16. In 2007, Sherpa Phurba Tashi reached the top of the world three times in one season. Phurba has climbed 35 times over 8000m summits – the most ever climbed by one person. Now he is partner of Mountain Experience Pvt. Ltd. On 11 May 2011, Apa Sherpa successfully reached the summit of Everest for the twenty-first time, breaking his own record for the most successful ascents. He first climbed Mount Everest in 1989 at the age of 29. One of the most famous Nepalese female mountaineers was Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, the first Nepali female climber to reach the summit of Everest, but who died during the descent.

Source: Slate.com, Sherpa Phurba Tashi (right) with Russell Brice, a leader of foreign expeditions to Mount Everest.

In conclusion, Sherpas epitomize the role of guardians of the Himalayas through their rich history, cultural heritage, and significant contributions to mountaineering. Originating from Tibet and migrating to the Himalayan region, Sherpas have woven their unique culture and traditions into the fabric of their mountainous homeland. Their deep-rooted Buddhist beliefs and communal values shape their way of life, guiding their interactions with the environment and climbers alike. In mountaineering, Sherpas are indispensable, using their specialized skills to support and ensure the safety of climbers on some of the world’s highest peaks. Their expertise and resilience in extreme conditions underscore their crucial role in high-altitude expeditions. As the custodians of the Himalayas, Sherpas balance their commitment to modern mountaineering with a profound respect for their sacred landscapes, safeguarding both their cultural heritage and the fragile environment they cherish.

Bibliography

- Ace The Himalaya, ‘The Life of Sherpas: Guardians of the Himalayas’, published on 4 June 2024, Available at https://www.acethehimalaya.com/the-life-of-sherpas/

- Sherpa Serku and Wengel Yana, ‘The Sherpas and Their Original Identity’, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2023.

- New World Encyclopedia, ‘Sherpa’, Available at: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sherpa

- Mosaic Adventure, ‘Unveiling the Legendary Sherpas of Nepal: Mountaineering’s Superhuman Heroes’, by Madhav Prasad, Available at: https://mosaicadventure.com/unveiling-the-legendary-sherpas-of-nepal-mountaineerings-superhuman-heroes/

- Altitude Himalaya, ‘SHERPAS OF NEPAL’, Author: Deepak Raj Bhatta, 7 July 2021. Available at: https://www.altitudehimalaya.com/blog/sherpas-of-nepal

- The Partners Nepal, ‘LIVELIHOODS OF SHERPA: Serve The Mountain Communities’, Uday Nachhiring.

- Footsteps on Mountain, ‘An early history of the 8000m peaks: the Sherpa contribution’, Mark Horrell, Feb 24,2016.

- Robert A. Paul, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle, ‘CULTURE SUMMARY: SHERPA’, eHRAF World, Available at: https://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu/cultures/ak06/summary

- ‘Sherpa: Trouble on Everest’, directed by Jennifer Peedom, Arrow Media, 2015 Available at: https://www.primevideo.com/offers/nonprimehomepage/ref=dv_web_force_root