How Sunil Gupta’s photography celebrated Queer in Delhi?

- iamanoushkajain

- September 27, 2024

On September 6, 2018, the Supreme Court of India overturned Section 377, a law from 1861 that criminalized homosexual relationships. This decision followed years of legal battles and activism by the Indian queer community to have homosexuality recognized as a natural phenomenon. Despite progress, homophobia is still prevalent in Indian society. However, there has been an emergence of films and literature depicting queer experiences, aiming to reduce stigma. In 1987, Indian-origin photographer Sunil Gupta showcased his photography exhibition “Exiles,” a groundbreaking collection capturing the gay community of Delhi against the backdrop of its historical landmarks.

Gupta’s motivation for creating Exiles was not solely to document the lives of queer men in India, but also to challenge the erasure of queer identities from art history, particularly outside of the Western world. On his website, Gupta reflects on his inspiration “It had always seemed to me that art history seemed to stop at Greece and never properly dealt with gay issues from another place. Therefore, it became imperative to create some images of gay Indian men; they didn’t seem to exist.” But had queer Indian men always been this marginalised? Ancient Indian notions of sexuality or sexual relationships were not heteronormative. The literature from the era provides many instances of queer people, or at least of their knowledge of it. Texts like Kamasutra explicitly mention gay sexual relations. Mahabharata also refers to the third gender when Shikhandin undergoes a sex change. Ancient and medieval Indian literature is replete with such examples. Even the Hindu law book Manusmriti, while forbidding homosexuality, assigns only a minor penalty in the form of a cold bath for the said offence. It was only in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century that the heteronormative character of the Indian society was solidified.

The emergence of colonialism and colonial legislature coincided with the arrival of Victorian morality and heterosexual monogamy. The people of the Orient were seen to be ‘over erotic’ or ‘overly feminine’ in a way that they were deemed unfit to govern themselves. One had to show himself to be anti-sexual or puritanical to be fit to run his country. Following these ideals, Indian social reformers tried to eradicate the erotic aspects of Indian culture, literature and religion, including homosexuality. This legacy was carried on by modern Indian nationalists and led to the imbibing of homophobia and puritanical Victorian morality into the Indian psyche.

Post-independence, India could not rid itself of this social attitude. Sunil Gupta was born in Delhi in 1953 to a north Indian father and a Tibetan mother. He grew up near the Humayun’s tomb and spent his formative years in Delhi. His family left Delhi for Montreal in 1969 when Gupta was 15. Gupta spent his life in Montreal, New York and London.

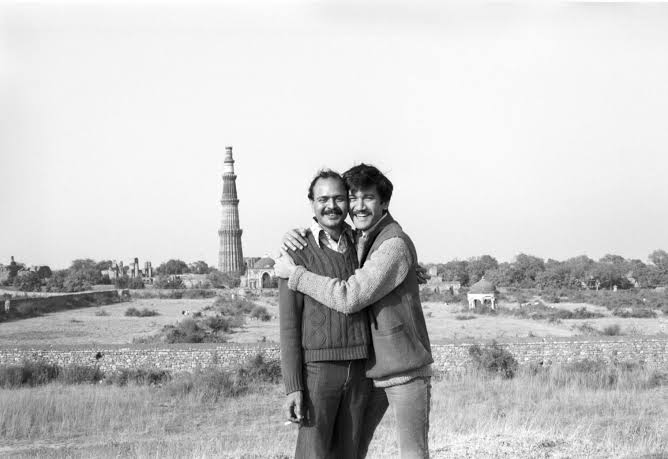

(Sunil Gupta- “Towards an Indian Gay Image- Saleem Kidwai and Me, Qutb Minar”, 1983; Source: Vadehra Art Gallery)

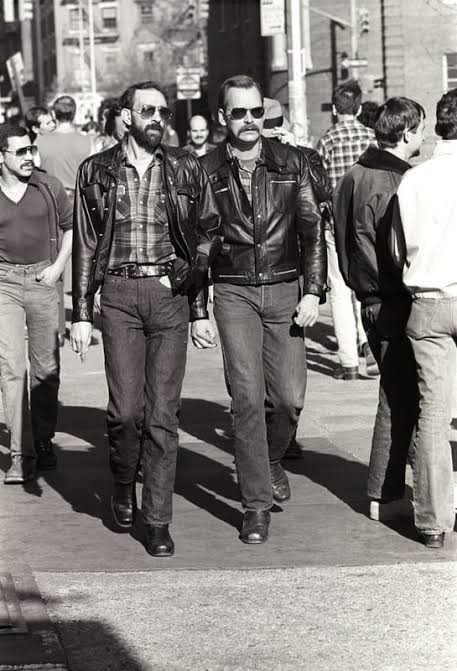

The first photography collection by Gupta was of Christopher Street in 1976. It was a popular gay hangout spot in Manhattan, and Gupta had published these images when he was a photography student in New York. This collection attempted to capture desire and liberation in 1970s New York. The subjects of the portraits were gay men dressed in the latest fashion, moving fearlessly across the streets of Manhattan, depicting the openness of the Gay liberation movement in North America. It stood in sharp contrast to the subjects of Exiles, a project that began almost a decade later.

(A photo from Sunil Gupta’s collection, “Christopher Street”; Source: www.sunilgupta.net)

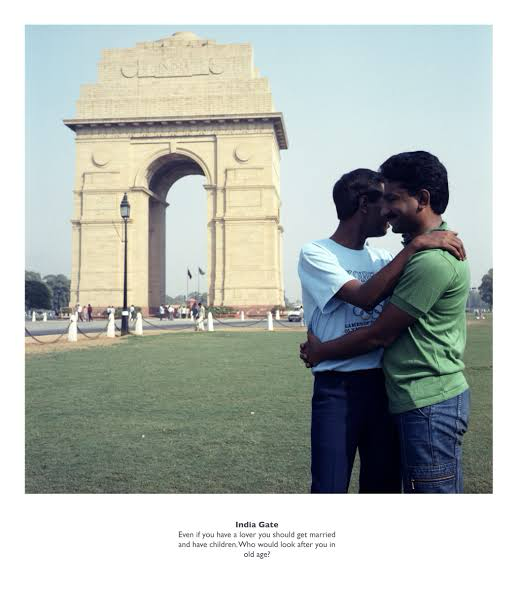

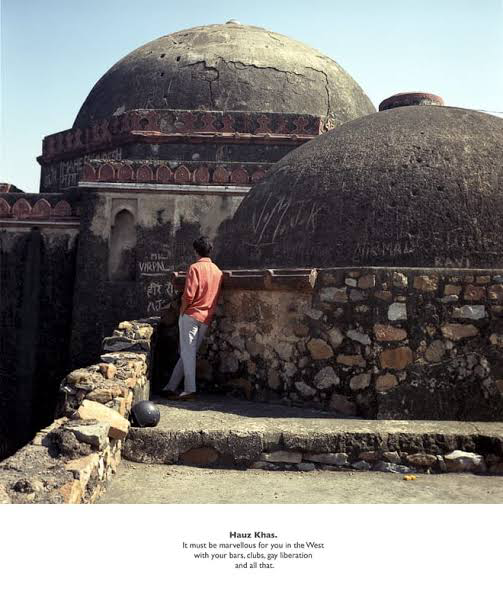

Exiles was commissioned by the Photographers’ Gallery in London. The photographs featured were captured in the form of a ‘staged documentary’ where the subjects and sites were both real, but rather than capturing the subjects in situ, the project tended to work with them artfully and meticulously, obscuring their identities yet depicting their nature. Sunil Gupta went with pre-arranged informants through specific places in Delhi where they struck poses. Sunil Gupta describes that most of his subjects were married men and due to societal pressures, maintained heterosexual family lives while simultaneously engaging in same-sex relationships. Due to the stigma associated with homosexuality, the subjects chose not to reveal their faces in the photos, barring a few. One such image is of a man standing at the Hauz Khas reservoir with his back towards the camera. His peach-orange-hued shirt contrasts the medieval worn-off stones of the monument. The walls around him wear the names and initials of people etched on them—MK Virpal, Nirmal, Ravi—dissociating him from the surroundings, since to us, the viewers, the subject has no name. The caption underneath reads, “It must be marvellous for you in the West, with your bars, clubs, gay liberation and all that.” Another frame from this photography series pictured against the backdrop of India Gate shows two men casually embracing each other. While public displays of affection between men are culturally acceptable in India, the presence of a professional photographer capturing this moment for artistic purposes drew attention and discomfort from onlookers. Gupta’s choice of location and his subjects’ poses blur the lines between platonic and romantic relationships, challenging viewers to question their assumptions about the nature of these interactions. This photo, which appears more liberating and celebratory than the previous one, is also followed by a rather gloomy caption, and reads, “Even if you have a lover, you should get married and have children. Who will look after you in old age?”

(From the series, “Exiles”; Source: www.sunilgupta.net)

(From the series, “Exiles”; Source: Vadehra Art Gallery)

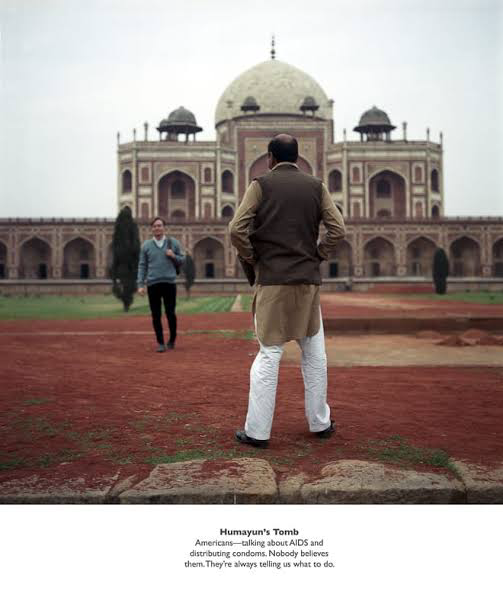

The locations for Exiles were the famous cruising sites of Delhi, where gay men met with each other and hung out. The subjects were captured in the cruising spots situated in the vicinity of their home. Another frame captures the Humayun’s tomb, a site that formed a major part of Gupta’s childhood. It shows a man (possibly middle-aged) in a brown tinted Kurta and a complimentary coffee-coloured waistcoat, observing a tourist who is not in focus but appears to be a foreigner, with the subject’s back towards the camera and is captioned, “Americans—talking about AIDS and distributing condoms. Nobody believes them. They’re always telling us what to do.”

(From the series, “Exiles”; Source: www.sunilgupta.net)

Flora Dunster looks at the title of the series in two contexts. One with Gupta himself being the exile, removed from the lives of his subjects, and another with the subjects exiling themselves with the imported conceptions of gay liberation and deferring to cultural expectations. This is true as many of the subjects agreed to the shoot only on the condition that the series would not be displayed in India. This privacy and anonymity gave them a chance to express themselves and embrace their true self, though only momentarily, to be captured in Gupta’s frame for posterity.

Exiles has become one of the most significant pieces of art history as it gave voice to the queer community of Delhi in one of the first attempts of its kind. It wedded the rich history and architecture of Delhi with the subjects and their sexuality, who, in popular belief, seemed to have no history. It connected the personal, private lives of his subjects to the broader public history of India, suggesting that queer people have always existed within this historical and cultural landscape, even if they have been largely invisible in its official narratives.Moreover, by placing his subjects in these spaces, Gupta reclaims them as queer spaces, challenging the heteronormative assumptions that often accompany such landmarks. In this way, Exiles serves as both a document of contemporary queer lives and a statement about the place of queer people within India’s broader historical and cultural context. The architecture becomes a silent witness to the intimate moments of Gupta’s subjects, suggesting that, despite their marginalization, they have always been part of India’s social fabric.

While talking about his own identity, Gupta said that one does not need to come to the West to come to terms with their queer identity. Gupta grew up watching Bollywood with its ‘big screens, high melodrama, high camp’. He says that while watching Pakeezah (1972), gay boys recognised that Meena Kumari was speaking for them. Indian queer people have their own sensibilities.

Almost four decades have passed since Exiles was first published, and Indian society has come a long way. From being reluctant about its inclusive past, where all sexual identities were accepted and celebrated, to the present day, where the pride movement has made us more accommodating towards queer communities, Indian society is coming to terms with its diverse sexual identities. The LGBTQ+ community is now a vocal part of Indian society. The acceptance, however, is not homogenous, with urban areas forming almost the entirety of queer people freely expressing themselves. Gupta did another photography series in Delhi between 2007 and 2012, “Mr Malhotra’s Party,” where he again captured young queer people of Delhi. This time, they posed, looking straight at the camera and proudly accepting their identities. This showed the acceptance of queer communities and the shedding of the colonial legacy that was bestowed in the form of homophobia.

References:

- Trivedi, Ira. “The Indian in the Closet: New Delhi’s Wrong Turn on Gay Rights.” Foreign Affairs, vol. 93, no. 2, 2014, pp. 21–26. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24483580. Accessed 22 Sept. 2024.

- Biswas, Soutik. “How same-sex unions are rooted in Indian tradition.” BBC, October 18, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-67131106

- Dunster, Flora. “Do You Have A Place?” Third Text, January 2021, DOI: 10.1080/09528822.2020.1860391

- Noor, Tausif. “Sunil Gupta Saturates his Photographs with Love and Sex” Frieze, 4 January, 2023.

- Gupta, Sunil. “Queer Migrations.” WestminsterResearch, 2018, pp 12-13.

- Gupta, Sunil. “Exiles.” Sunil Gupta

https://www.sunilgupta.net/exiles1.html

- DMello. Rosalyn. “Exiles and the Queerdom.” stirworld, October 24,2022, https://www.stirworld.com/think-opinions-exiles-and-the-queerdom

- Holland, Oscar. “This photo of male intimacy in 1980s India was more subversive than it seems.” CNN, February 8, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/sunil-gupta-india-gate-snap/index.html

- Gupta, Sunil. “Christopher Street, New York 1976.” Sunil Gupta, https://www.sunilgupta.net/christopher-street-new-york-1976.html

- “Sunil Gupta-Christopher Street.” Hales, https://halesgallery.com/exhibitions/136-sunil-gupta-christopher-street/

- Gupta, Sunil. “Mr. Malhotra’s Party” Sunil Gupta, https://www.sunilgupta.net/mr-malhotras-party.html

- September 27, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- March 27, 2024

- 10 Min Read

- August 12, 2023

- 7 Min Read