The History and Adaptation of Eau de Cologne in Indian Aristocracy

- iamanoushkajain

- July 26, 2024

Cologne

They say smell is memory. One cannot forget the smell of their mother in adulthood and it is so beautifully imprinted in our memory that we fail to recognise how these smells and their memories protect us. This might work even in cases where the particular person or the memory is not that dear. Eau de Cologne is one such thing. Originating in the year 1709 in Cologne located in Germany the product seemed to have brought back a pile of memories for Johann Maria Farina (Brewer, 1889). Although initially thought to be capable of curing bubonic plague as it was made from cologne water which had this particular reputation the product soon gained popularity to hit the market with the highest price. In no time the product became famous and gained its position so high that it was mostly out of the rich local people. Then came war and slowly colonialism. ‘Eau de cologne’ survived plagues, the Industrial Revolution, two world wars, colonialism and finally globalisation before it reached the Indian aristocrat washrooms to tell the whole tale.

(vintage advertisement of Eau de Cologne, source: alamy)

History of Eau de Cologne

From the name it might not be evident at the beginning but ‘Eau de Cologne’ actually refers to the city cologne of Germany. If translated then the entire name stands as ‘water of cologne’. This water was previously thought to have the power to shoo away bubonic plagues. The essence was launched by Giovanni Maria Farina in 1709 who was an Italian perfume maker hailing from Santa Maria Maggiore (Hussain, 2021). By describing the essence of cologne she wrote to her brother in a letter the following “I have found a fragrance that reminds me of an Italian spring morning, of mountain daffodils and orange blossoms after the rain”. From this beautiful allegory later he named this particular essence as ‘ Eau de Cologne’. Perhaps this is how the essence of a place and memories associated with it get transmitted in a bottle.

Soon, with its wide popularity the product got a promotion and it started to be used in almost all European households. It got so popular that many businessmen started to manufacture the same Eau de Cologne and sell it under the same name. The price reached so high that it soon required half the total annual salary of a civil sergeant to get one single vial. The formula of Eau de Cologne although remains secret to date. However, for the record, the popular knowledge goes that the essence has been created with the help of extract oils from lemon, tangerine, bergamot, blood orange, jasmine, olive, oleaster and even tobacco (Nechtman, 2006).

(the traditional Eau de Cologne, source: alamy)

The essence was then further developed by Wilhelm Mulhens and it has been produced in Cologne since 1799. The original Eau de Cologne 4711 refers to the location it was produced in in Glockengasse N0 4711.

In 1806 the essence reached Paris with the help of Roger and Gallet. This is the company that has the right to the product to date. Paris became the capital of luxury items and aristocracy after surviving the European wars and plagues. This is also probably the place from where the French or European aristocratic ladies have picked up a particular product or product genre (as it has already become one by then). With them, the generic ‘concept’ of cologne was brought to India as their husbands got jobs in this country to run the British empire.

The concept of fragrant smells and how they survived

In the turbulent times, the most fascinating thing that India witnessed was the amalgamation of cultures despite the impositions. The Europeans came to India to utilise the natural resources and make their empire rich but in the process, they left their imprints which eventually made this country more captivating and enigmatic as a cultural resource. However, the concept of smells and their abundance in aristocracy was not among these. Before the British era, there were Ittars brought by the Islamic rulers, the fragrant smoke (ancient culture from medical Ayurvedic practices), sandalwood, different types of herbs and many more (Minter, 2012). Smells and identities are intertwined. Hence. As the feathers of Europe got attached their smell and history got attached to the Indian Identity.

The common man and woman of the third-world country have never been in a position to afford a concept of luxury smells. The beautification of the soul is a far-fetched dream that is often a burden on the half-fed swollen stomach. However, still, we learn from the tribal communities that if nature is kept and nurtured in life as a cherished family member then one would never be deprived of anything. We have seen women travelling in the woods and collecting fragrant flowers, and we have seen aristocrat begums adorn themselves with ittars and fragrant smokes. But the colonial luxury items were been introduced as a form of detachment from the existing culture.

(A British advertisement of 80s, source: pinterest)

So, luxury smells are luxurious because they are mostly imported. The ittars and their usage got popularised in the country as they were initially imported from Persian culture. This whole business of cultural communication and cross-country product delivery was something to be very much obeyed by the economic suitability. This is always in the control of the rich. On the other hand, the common people have always been made to live in a reality where they were forced to live in reverie about ‘one day being rich’. This dream of being rich has mostly captured the imported goods and made their entry into popular lives possible.

How Eau de Cologne transferred to Indian women

Luxury perfumes were brought by the memsahibs. As soon as men started to go to the office and obey their white-skinned bosses women were forced to become their eligible counterparts by choice or not. Today, across the rich and aristocratic families one can easily find traces and memories of that era. It is reflected in the cloths, in the tablecloths, in the kitchen utensils and even in the bathrooms (Hussain, 2021). The usage of Eau de Cologne is one of such elements that is one of them. The most ancient smell that originated in the West is fabricated with the amount of history it has been carrying with it.

In one of the short stories of a colonial white woman writer Flora Annie Steel, we find an enigmatic presence of Eau de Cologne. In Feroza, the central character who is a married Muslim woman gets betrayed by her British-educated husband and she commits suicide. Across the story we find Feroza trying her utmost to get prepare for a complete and fulfilling conjugal relationship with her husband Mir who is sent to England to prepare as a barrister. Here in India, the girl gets to a certain Miss Smith. This is the lady strategically located in India for the sake of educating young women. Naturally, this woman is the ‘go-to’ resort for Feroza. Upon receiving news of Mir’s second marriage Feroza runs to this Miss Smith for courage and comfort. Instead of facing the poor girl she covers her face with a handkerchief of Eau de Cologne and begs her servants to take her away. Later, she laments again and wipes her tears away with the same handkerchief when the poor girl is dead by suicide. This death might look like that but in reality, it is a murder. Murders are required to maintain cultural bonding and are often counted as collateral damage when a larger-sized appropriation is taking place. Mir’s position as a hybridised new Indian man with all the desires is one side and the failure of Feroza and her aspirations is another (Roy, 2010). Eau de Cologne however manages to get in as a comfort to the white lady who is also a victim of this whole drama but has a protection. This protection was most definitely envied by the aristocratic women of Indian origin and they wanted to have it for good.

Luxury perfumes and their stay

Not everything that is good stays and not everything that stays are good. This is something that the history of colonialism teaches us through and through. The reason that ‘Eau de Cologne’ in particular stayed and grew with the advancements of the societal reflection is probably that by the time it reached India, it had already been transformed into a genre/category of luxury product that a single product. The usage and popularity were already so high among the people who used it that as they travelled it came with them. It is interesting to note that one product that was used by the common or middle-class people of Europe could not pierce through any more than the aristocratic class of India. One possible reason behind this could be the wide difference in the treatment of the colonialists for the native classes (Zumbroich, 2002). The aristocratic class was been prepared as a class of clergymen who would run the country from an administrative perspective. The poor class was been treated as animals. Hence, the concept of luxury items that too one used by the rulers is beyond imagination.

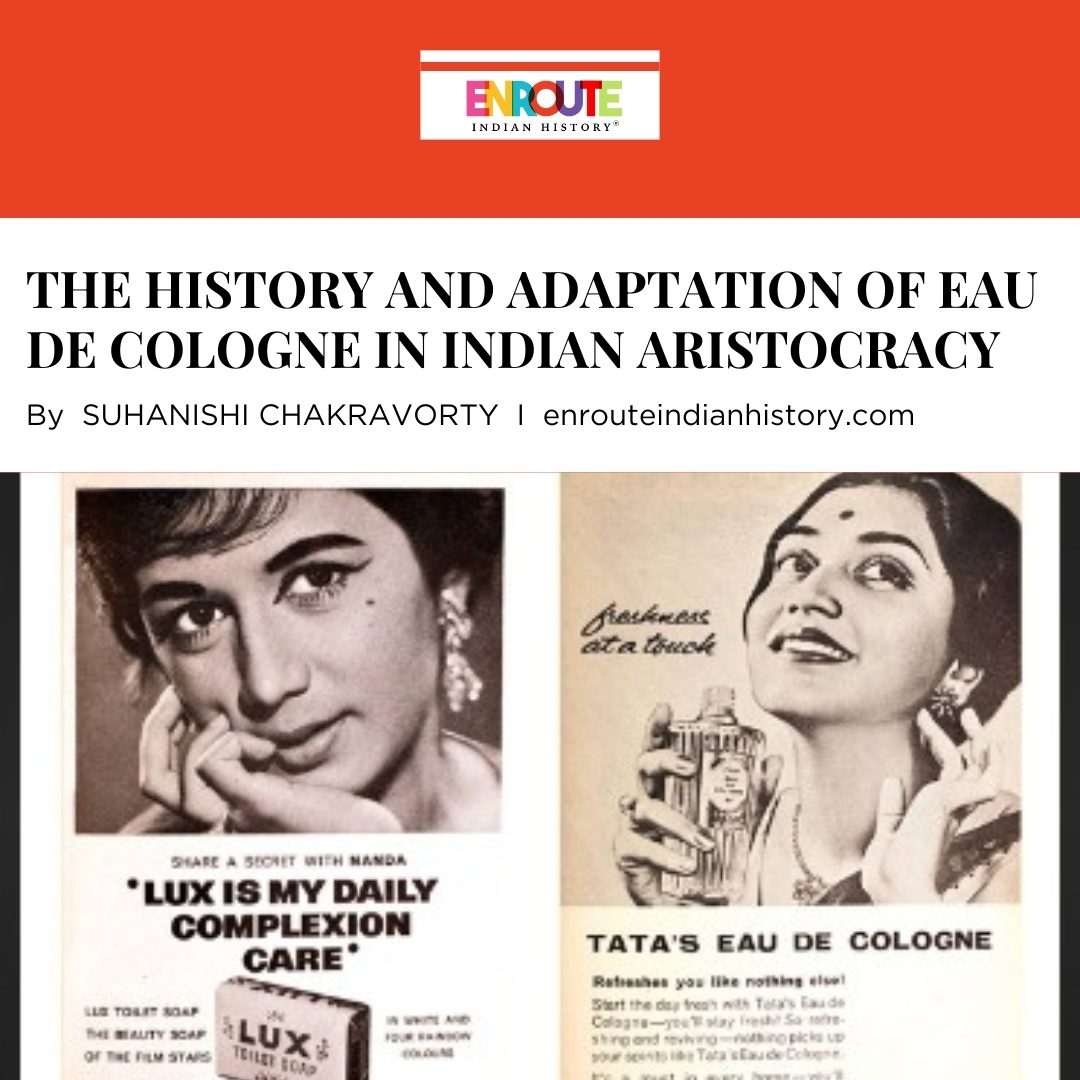

(Indian women in Eau de Cologne and Lux, source: nakhrli)

Conclusion

The smell is a memory and hence their integration in lifestyle is probably a calling to the past which is so cherished while the willingness to take the same in the future is prominent. In advertisements of the British commodities, one can find possible repetitions of the already prevalent cultural practices like portraying women as Laxmi, the homemaker along with a conscious triggering to the aspirations that these women will never be able to achieve. That is to be their partner’s equal companion. As the British went away Eau de Cologne somehow managed to stay back at the dressing tables of these aristocratic women who had now taken the responsibility to mimic their teacher, the veteran memsahibs. Eau de Cologne still proudly takes place in some of the wardrobes, dressing tables and writing desks of our grandmothers and mothers, shouting all this history in one single smell, which began on that fresh Italian morning daisy garden.

Bibliography

Roy, S., 2010. ‘a miserable sham’: Flora Annie Steel’s short fictions and the question of Indian women’s reform. Feminist Review, 94(1), pp.55-74.

Hussain, M., 2021. Combining Global Expertise with Local Knowledge in Colonial India: Selling Ideals of Beauty and Health in Commodity Advertising (c. 1900–1949). South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 44(5), pp.926-947.

Nechtman, T.W., 2006. Nabobinas: Luxury, Gender, and the Sexual Politics of British Imperialism in India in the Late Eighteenth Century. Journal of Women’s History, 18(4), pp.8-30.

Minter, S., 2012. Fragrant plants. In The Cultural History of Plants (pp. 242-260). Routledge.

Zumbroich, T.J.,2002 From mouth fresheners to erotic perfumes: The evolving socio-cultural signiicance of.

Brewer, E., 1889. EAU DE COLOGNE AND ITS HISTORY. The Leisure hour: an illustrated magazine for home reading, pp.102-103.

- Aristocratic perfume traditions in India

- Colonial influence on Indian perfumes

- Eau de Cologne adoption in India

- Eau de Cologne in colonial India

- History of Eau de Cologne in India

- Indian aristocracy and perfumes

- Luxury perfumes in Indian history

- Luxury scents in colonial India

- Perfume culture in Indian aristocracy

- Women and perfumes in Indian aristocracy