How the Cow Came to be revered as Gau- Mata In India?

- enrouteI

- January 4, 2024

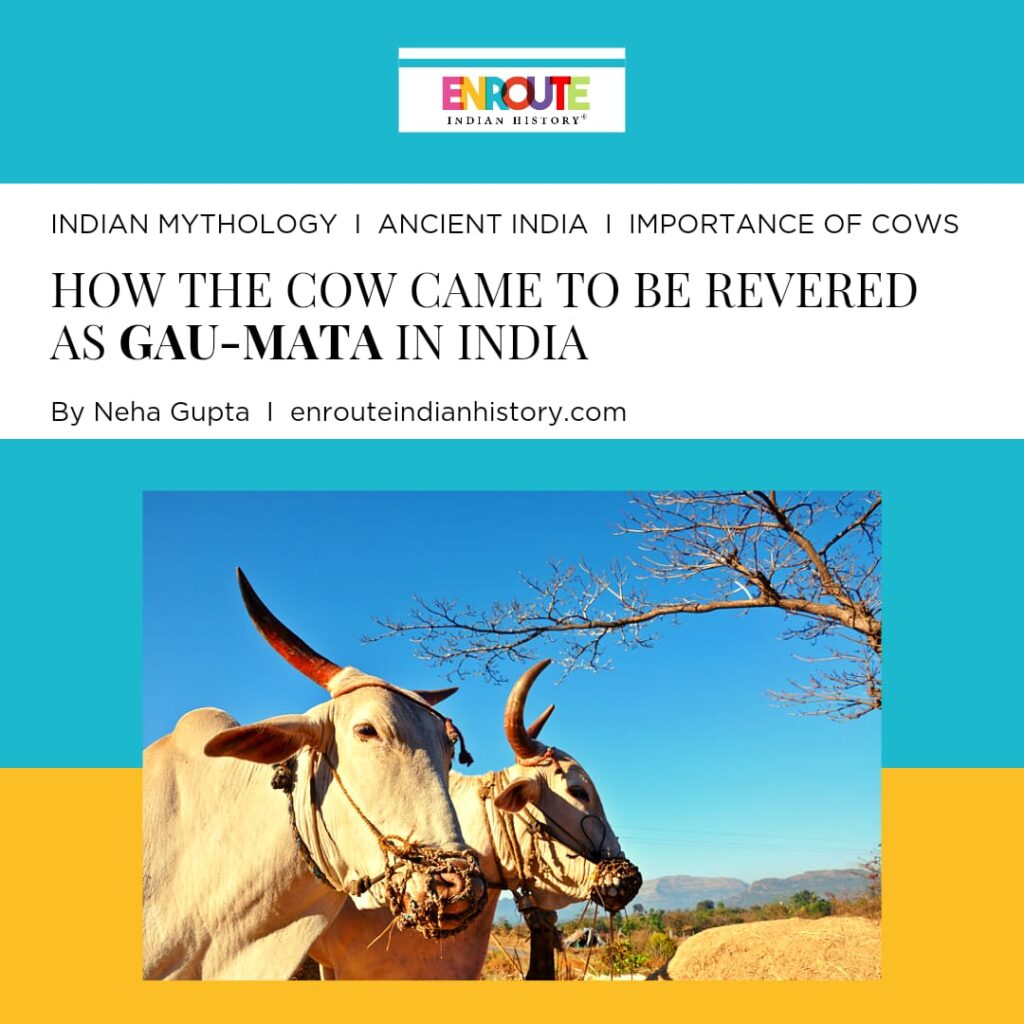

In the animal kingdom, only the cow gets referred to as “gau-mata” by Hindus, enjoying a reverential position like none other. By being labeled as the ever-giving, nourishing mother, she is treated as one who is worthy of worship and must be protected from harm.

While the economic use of the cow cannot be denied in an agrarian country like ours, its sacred identity has been formed and built over the ages. The subtle message of the cow as holy has been imbibed over centuries so the cow has now become an indispensable symbol of the Hindu culture.

The Cow In Ancient India

In the Vedic literature, historians have noted repeated references made to the cattle – which are a combination of the ox, the cow and the bull. The reference to this cattle combination is notably more than that made to any other animal in the Vedic literature, which points to the importance of cows. The war booty mentions standard items such as the bull and the ox, which were primarily used for agricultural and transportation purposes along with cow produce such as milk and milk products.

Apart from its economic value, the cow was also used in sacrificial rituals, which were an important aspect of the Vedic society in ancient India. Milk and ghee were also essential offerings made during these sacrifices. In the Vedic times, the cow wasn’t treated as a holy being, rather as a useful one, often an indicator of an individual’s wealth.

The concept of ahimsa or non-violence towards all living beings was introduced by the Upanishads. While cattle continued to be used for sacrificial offerings, it was reduced for esteemed guests, on momentous occasions.

It was only with the influx of Jainism and Buddhism in the sixth century BCE and fifth century BCE respectively, that killing of cows and other cattle were rigidly opposed under the ahimsa doctrine followed by both these religions. This non-violent approach was further adopted by Emperor Ashoka. He made Buddhism an imperial religion in his court and began practicing vegetarianism, which made the killing of cows for beef both impious and illegal. Since his reign expanded to the entire Indian subcontinent, except for some parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, his rule helped curtail the consumption of meat.

The Depiction of Cow in Hindu Mythology

During the Gupta Age which existed from early 4th century CE to early 6th century CE, when arts and literature flourished and the two most important epics of Hindu religion – Ramayana and Mahabharta – were finalized, the cow emerged as a mythical heroine. Hitherto, it had been a valuable resource, sought after for its products. But from the Mahabharat emerged the story of the Kamdhenu cow, which can be termed as the foundation stone in the creation of the holy identity of the cow, solidifying the importance of cows in Indian mythology and conscience.

( 14 gems of samudra manthan | The Moral Stories)

The story of the Kamdhenu goes that during Sagar Manthan between the Devas and Asuras, the first thing to be churned out of the ocean was the “Kalkoot Vish ” or poison, which was drunk by Lord Shiva. The next outcome of this churning was the Kamdhenu or the wish-fulfilling cow. She was young and tender and was welcomed by all saints and sages present. Kamdhenu was given to Maharishi Vashishta for nursing. He went on to create a separate “Gau-Loka ” in her honor. This instance shows the reverence accorded to the cow, treating her as an important being deserving of a separate, sacred and pure land for her kind.

( Cow embodies Hindu cosmology | The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Mahabharta also tells the story of the sage Dhanwantri who worshiped Kamdhenu and was her fervent devotee. With her blessings, he was able to make “Panchagavya” – a medicine made out of 5 miracle products of the cow – milk, curd, ghee, urine and dung. It is interesting to note the renewed interest in Panchagavya as an immunizer amongst modern scientists.

Apart from establishing the cow as a sacred being, the Mahabharata also shows how the entire economy of that society was counted in terms of the number of cows that were owned by an individual, which could begin from ten, hundreds, thousands and go to lakhs and crores. This shows how Indian Mythology repeatedly stressed on the importance of cows.

We have the instance of “Maharaj Virad”, in the Mahabharata era, who had a big herd of cows, which was known as his main property. Maharshi Chyavan was a great worshiper of cows and so was “Maharaj Rikthambhar ”. The story of the great King “Dilip”, an ancestor of “Bhagwan Ramachandra” is a popular folktale, where he is believed to have challenged a lion who wanted to satiate its hunger by eating the cow “Nandini”, by offering himself instead of the cow.

The Indian mythology is full of descriptions of other cow-worshippers like Pandu’s son Sahadev and Raja Virad, and in later times, saints like Santh Namdev who were known for their dedication to the Cow. Indian mythology can be easily accredited for firmly establishing the importance of cows in the Indian psyche as our Gau-Mata – the gentle, nourishing mother who needs to be worshiped.

(Krishna with Yashoda milking cow | Dolls of India)

It was later with the rise in Vaishnavism that Krishna’s cow became a figure of love and devotion in every Hindu household. Gokul, where Krishna was raised, was the land of shepherds. The cows were his constant companion, and the maakhan prepared from the cow’s milk was his favorite dish. In fact, Krishna and Balram are depicted not just as devotees of the cow, but as their protectors. By incarnating as shepherds, Krishna and Balram spread the belief that cow worship can help one attain moksha and so one must protect them.

(Act of cow worship | Bharat Darshan)

The Hindu calendar continues to reserve days for exclusive worship of the cow in a year. Three days before Diwali, Bachvaras or Vasubaras are celebrated, wherein people worship cows. Another popular festival, Dhanteras celebrates and worships cows along with the sage Dhanwantri, who gave the Panchagavya medicine. One day after Diwali, Balipratipada or Padwa is celebrated in some parts of the country, in honor of the cow.

Gau-daan or donation of cows continues to be considered a most noble act in contemporary society, often hailed as the cure for rashi-dosh.

Cow as a symbol of struggle and resistance against foreign forces

In modern history, the cow has served as a symbol of struggle against foreign rule, whether it was against the Mughals or Britishers – both of who liked to consume beef and tried to curb down on the superstition of worshiping cows.

The story of Chatrapati Shivaji as a young boy during the reign of Mughal emperor Aurangazeb challenging a butcher, who was forcibly taking a cow for slaughter, is a popular one. Not only is Shivaji remembered for rescuing this cow, but for also killing the butcher in a symbolic act of protecting the Gau-mata and his religion.

The protection of cows became a strong political symbol during the freedom struggle too. Dayanand Saraswathi set up Gaurakshini in 1882 and made “cow solidarity” an important feature of his concept of Indian solidarity against Britishers. Bal Gangadhar Tilak started the Shivaji festival and made the cow an integral part of it. Mahatma Gandhi also spoke for the protection of cows and recognised it as an inseparable Hindu identity.

Today, the cow is accepted by all sections of Hindu society as a generous, docile creature who is a sacred symbol of life itself and must be protected from harm. The cow’s favored position in the long annals of Indian history is testament to its value. It continues to be held in high regard and treated with respect not just for its produce, but also for its symbolic presence of a divine benefactor of human beings.

References

- AN Pal, (1996) ‘The Sacred Cow in India: A Reappraisal’ Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/41919804

- WN Brown, (1964) ‘The Sanctity of the Cow in Hinduism’ Available at https://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/1964_16/5-6-7/the_sanctity_of_the_cow_in_hinduism.pdf

- https://dahd.nic.in/related-links/chapter-i-introduction

- https://dahd.nic.in/related-links/chapter-i-introduction

- April 25, 2024

- 14 Min Read