India’s First Female Director: Fatma Begum

- iamanoushkajain

- February 13, 2025

- A Cinematic Legacy: India’s First Female Director, Fatma Begum

Article By – Inika Choudhary

At the time of a highly male-dominated film industry, so much so that even women characters were played by men, we hear of a female director who broke the glass ceiling to emerge as a leading actor, scriptwriter, and director, delivering phenomenal works in a career that spanned over 16 years. Fatma Begum is revered as a pioneer in Indian filmmaking, a trailblazer who indulged in roles that covered all aspects of cinema–from writing and directing, to acting and production. Her work, though minimally documented and unavailable for the current generation’s first-hand perusal, is a testament to a fine legacy during a precarious period of transition in Indian cinema, which set the wheel in motion for women to engage with the Indian entertainment industry.

Early Life

Born in 1892 to an Urdu-speaking Gujarati Muslim family in Sachin (part of present-day Surat in Gujarat), Fatma Begum was supposedly married in 1906 to the Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire, Nawab Siddi Ibrahim Muhammad Yakut Khan III Bahadur, the Prince of Sachin. Several doubts revolve around the authenticity of this ‘marriage’, owing to the fact that there is no available legal record of the same and the Nawab too never acknowledged the children borne by Fatima as his own. Rashmi Sawhney, a prominent researcher on the life of Fatma, however, argues for an interesting hypothesis. The first wife of the Prince of Sachin, as per historical records, was called Fatima Sultan Jahan Begum Sahiba, corroborating our assumption of the aforementioned marriage. But family accounts state her to have passed away in 1913, at around 21 years of age. A story of fabrication thus comes into play here. Since female actors and participants in the film industry were highly frowned upon in the society of the time, it can be conjectured that the family found it much more convenient to declare Fatma dead rather than deal with the repercussions of a woman making it big on the screens.

Sawhney also writes that it is perhaps in 1913–the year Fatma was proclaimed dead–that she migrated to Bombay (now Mumbai) with her daughters in the hopes of traversing the lanes of Indian cinema. It was then in 1913 that the ‘mother’ of Indian cinema began her journey, alongside her contemporary–the renowned Dadasaheb Phalke, often venerated as the ‘father’ of Indian screens. She debuted as an actor playing the role of Subhadra, alongside her daughter Sultana in Manilal Joshi’s Veer Abhimanyu in 1922, produced by Ardheshir Irani. Other films of Fatma, all released in 1924, include Sati Sardaba, Prithi Vallabh, Kala Nag, Gul-e-Bakavali, and Mumbai Ni Mohini in 1925. She also starred in talkies such as Nanubhai B Vakil’s Sevaa Sadan (1934) and Homi Master’s Punjab Lancers (1937). Her last acting role was in the 1937 movie by G. P. Pawar, Duniya Kya Hai.

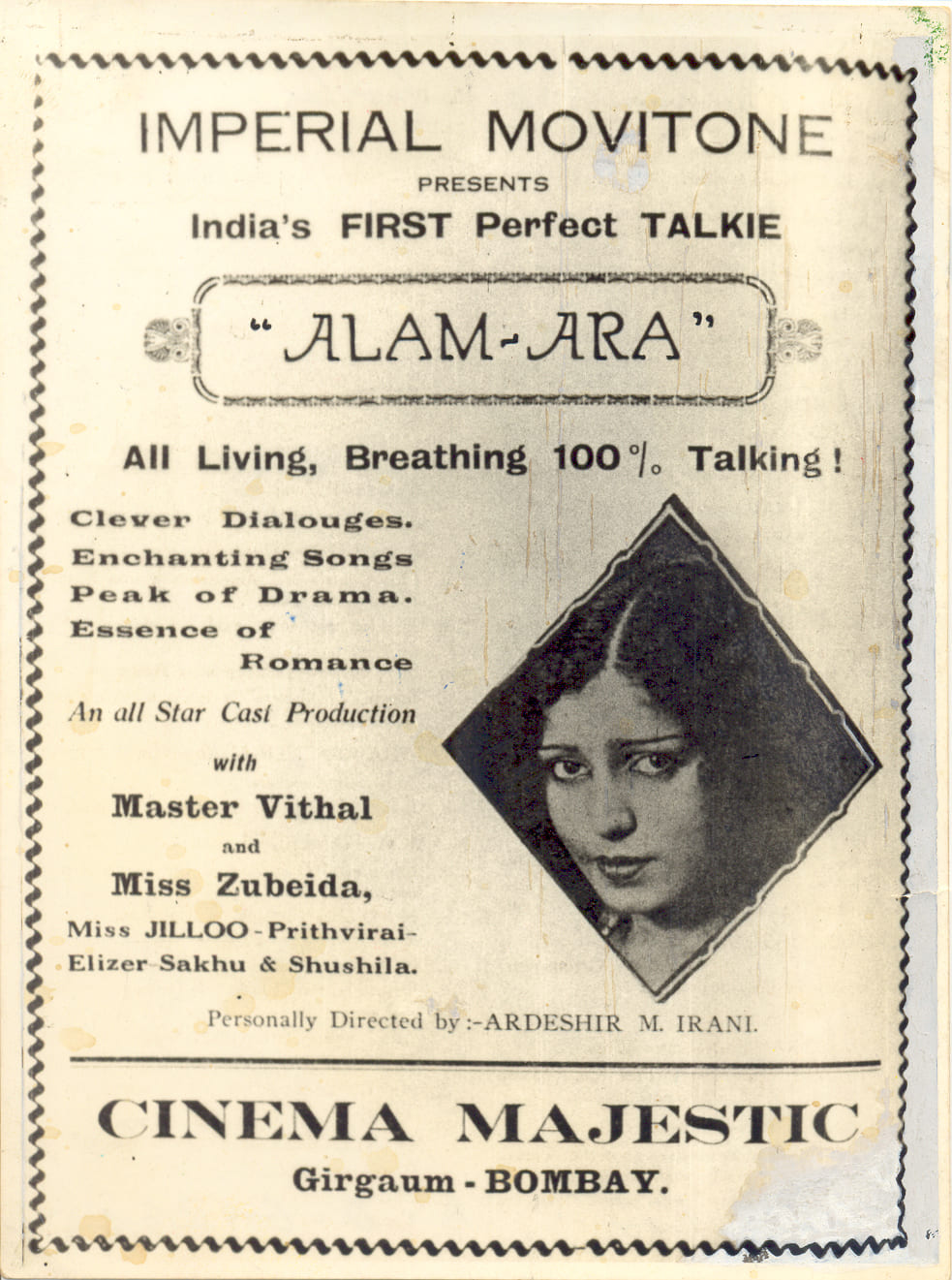

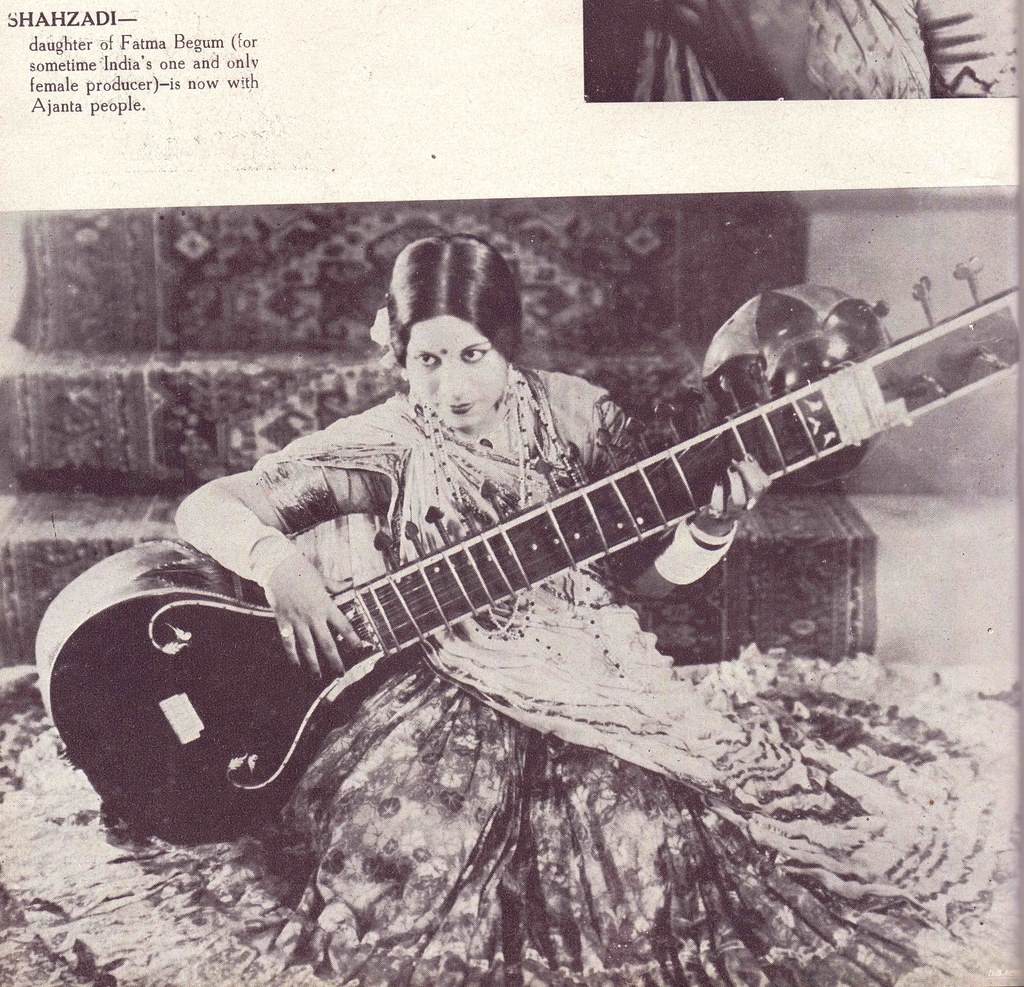

Fatma’s three daughters, Zubeida, Sultana, and Shehazadi, went on to become famous actors. Shehazadi was known to be a keen dancer and performer, and both Sultana and Zubeida too became leading stars of the 1920s silent films era, with Zubeida playing the lead fairy-princess Bakavali in Kanjibhai Rathod’s Gul-e-Bakavali, also featuring Sultana. Zubeida later also starred in India’s first talkie, Alam Ara in 1931, and became quite popular during the 1930s, with the two sisters being some of the most highly paid actresses of the time. Even as questions persist over Fatma’s married life due to her associations with the film industry, Zubeida married Raja Dhanraj Giri Narsinghji Gyan Bahadur of Hyderabad, belonging to a family of prominent bankers in the Nizam’s court, in quite a contrast to what we believe to be a failed marriage in Fatma’s case.

The Fatma Film Corporation

In 1926, Fatma Begum set up her production house, the Fatma Film Corporation, later rebranding it as the Victoria Fatma Film Corporation in 1928. Her first film, Bulbul-e-Parastan (Bird of Fairyland, 1926) was both directed and produced by her. This lavishly produced film, one of the very firsts in the fantasy genre, featured her daughters Zubeida and Shehazadi and used trick photography coupled with special effects to weave the narrative of a queen who used her magical powers to bring order to the world. Anusuya Kumar talks of how the inclusion of Persian and Armenian fairy tales as well as the Arabian Nights portrayed a shift away from the old tradition of Hindu mythological and religious depictions on the screens and even motivated the production of later fantasy films like Alladin and the Wonderful Lamp, Afghan Abla, and Alam Ara, all in 1931 by Fatma’s friend and colleague Ardheshir Irani.

Her later films include The Goddess of Love (1927), Heer Ranjha (1928), Chandravali (1928), Kanaktara (1929), Milan Dinar (Meeting Day/Test of Love, 1929), Naseeb Ni Devi (Lady of Fortune, 1929), and Shakuntala (1929), all with female-centric roles that explored the creative and sexual sides of the lead characters. Amounting to around nine in total in a span of three years, all of these films were produced by Fatma, and she even wrote, directed, starred in, and worked on special effects and photography for many of them. Even though 1929 was unarguably the year of the highest productivity for Fatma, it also marked the end of production, for after this, she was embroiled in numerous legal cases that ultimately led to the shutting down of the studio.

Several newspaper reports dramatically detail the legal trials against payment faulters made by Fatma, apart from charges of fraud, cheating, criminal breach of trust, forgery, theft, and even allegations of swindled jewellery. These accounts also tell us how Fatma drove a Rolls Royce and lived in the Carter Road area, a posh neighbourhood in Bombay, with her production house set up in Bandra. She, along with her daughter Sultana Jilani was reported to have been present in the court pleading their case, while being ‘lightly veiled’. Fatma was also purportedly well-versed in English, knowing how to read, write, and speak in the language–a feat she reportedly denied during court proceedings.

Fatma’s production work lay at the cusp of Indian cinema’s transition from silent to talkie films. Several small-scale producers during this evolving era had to shut down their studios in the face of rising competition, and one can only imagine the hardships a female producer would have had to go through in such a time. It is easy to view the “tremendous instinct for survival” that was characteristic of female pioneers who had to survive during the time. This large number of legal cases and the reports are instrumental in helping shape the history of the era–which otherwise remains largely obscure when it comes to female filmmakers and their stories.

Conclusion

Fatma Begum died in 1983, aged 91, leaving a long legacy of female-centric narratives in Indian cinema in her wake. A look at her ancestry reveals traces of East African origin, particularly the Siddi or Habshi community of the Bantu tribe in Ethiopia. The Siddies were largely slaves but also soldiers and traders, brought to India initially by the Arabs from the 8th century onwards and later by the Portuguese in the 15th century. It is in this context that her life and journey become all the more nuanced; for Fatma was not only a Muslim woman making her way in a highly male-dominated industry, she was also of East African descent, shattering all barriers of indigenous monopoly over production.

A lack of the practice of preserving film records during that time leaves us with little evidence of any original works of Fatma, which ultimately is a major gap in the research undertaken on her journey. We do not today have the prints of any of her phenomenal films, thus reducing her creation to imagination. It is indeed surprising to see that the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) has not even a single slim monograph of the first female director in all of South Asia. Should the prints become available through the efforts of archival agencies and the NFAI, the life and times of Fatma Begum will receive unprecedented recognition, showcasing a mastery of craft well ahead of time.

References

- Sawhney, Rashmi. “Fatma Begum, South Asia’s first female director.” Industrial Networks and Cinemas of India: Shooting Stars, Shifting Geographies and Multiplying Media (2020).

- Erdogan, N., and E. Kayaalp. ““Uncontained” Archives of Cinema.”

- https://feminisminindia.com/2017/03/12/fatma-begum-essay/

- https://www.scaruffi.com/director/begum.html

- https://criticalcollective.in/SpecialProjectEssayListing.aspx?id=1536

- http://www.asiateca.net/2020/04/16/fatma-begum/

- https://www.cinestaan.com/articles/2020/mar/24/25053

1: Portrait Image of Fatma Begum. Retrieved from an article titled ‘Fatma Begum, First Woman Director of Indian Film,’ published by the Golden Globes, dated 15 March 2022.

2: Poster of South Asia’s First Talkie, Alam Ara, starring Fatma’s Daughter Zubeida. Retrieved from an article titled ‘Making of Alam Ara: An Interview with Ardeshir Irani’, published by Garga Archives, written by B D Garga, and dated 1980.

3: Photo of Fatma Begum. Original source unknown, retrieved from Wikimedia.

4: Shehazadi, Daughter of Fatma Begum. Retrieved from an article titled ‘Fatma Begum India’s first female director’, published by Asiateca, dated 16 April 2020.

5: Sultana, Daughter of Fatma Begum. Retrieved from an article titled ‘Fatma Begum India’s first female director’, published by Asiateca, dated 16 April 2020.