Ink, Irony, and Empire: Tracing the Roots of Caricature in Colonial India

- iamanoushkajain

- May 8, 2025

By Vaibhavi Danwar

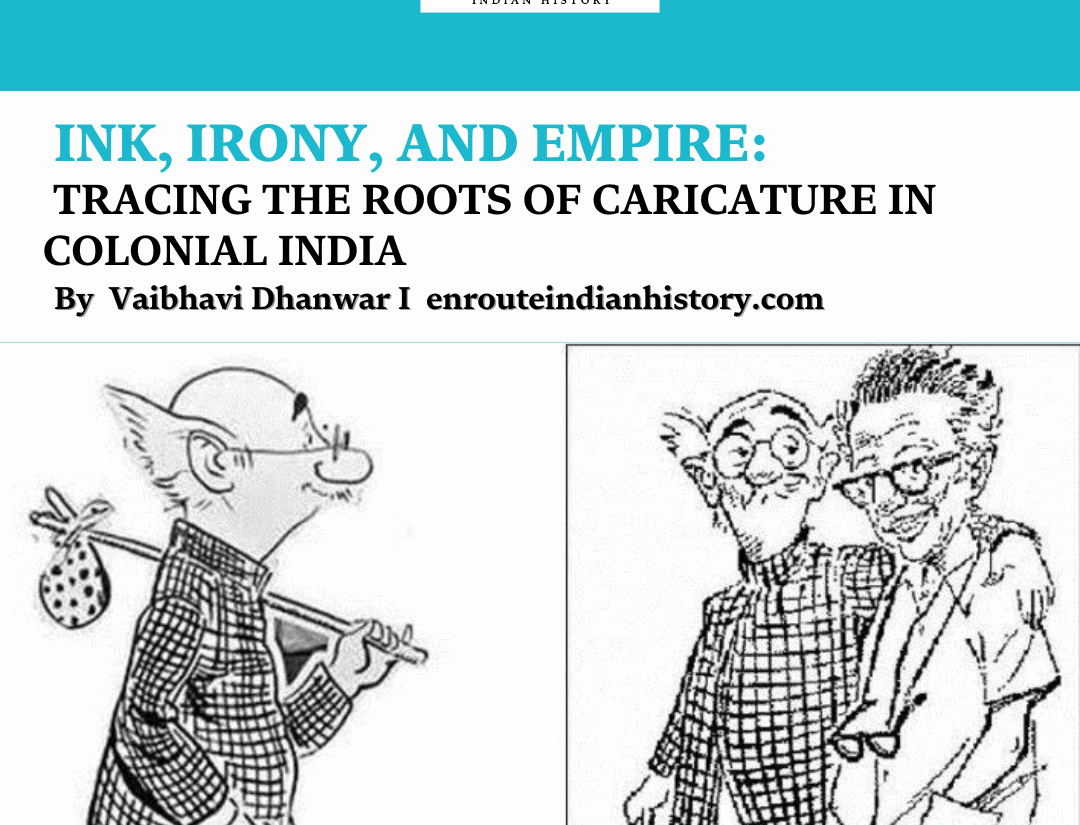

Long before social media memes and stand-up comedy took center stage, the earliest sparks of Indian satire flickered in the bold lines of hand-drawn caricatures. This article journeys back to the 19th century, when Indian artists first began wielding pens not just to sketch but to speak. Under the shadow of the British Raj, caricature emerged as a sharp and subversive visual language that challenged colonial authority, ridiculed cultural hypocrisy, and gave voice to an increasingly self-aware society. Publications like The Hindi Punch mirrored and mocked their British counterpart Punch, but soon developed uniquely Indian tones mixing wit with nationalist critique.

From Imported Ink to Indigenous Irony

The history of caricature in colonial India starts not with indigenous brushes but with foreign satire, British, stinging, and wonderfully overdrawn. As India entered the age of print under colonial domination, its visual culture assimilated and then reworked British conventions into something distinctively its own. The caricature, popularized by colonial newspapers and borrowing from London’s Punch magazine (established in 1841), evolved as a critical prism through which Indians started looking at and satirizing colonial masters as well as issues of society. What began as imitation soon transformed into a powerful tool of resistance, satire, and political awareness. Magazines during that period primarily served British officials and expatriates, representing Indian customs and public life in a frequently mocking, orientalist manner. Indians were represented as either inept figures of derision or idealized objects of imperial observation. Satire in these magazines was mostly intended to amuse the British and uphold colonial superiority. Publications such as The Hindi Punch (founded in 1878) and Oudh Punch (founded in 1877) represented a revolutionary change. Based on the British Punch, these magazines borrowed the format of grotesque visages, symbolic props, and humorous captions but reversed the direction of the gaze. They now directed the satire against both colonial domination and Indian social hierarchies, and thus a new voice could find expression within the context of a pre-existing colonial instrument.

These early Indian satirical journals were significant for creating a new idiom of resistance not through open rebellion, but through humor and irony. Unlike overt political speeches or editorials that risked censorship or legal action, cartoons allowed subtle critique. Caricatures in the late 19th century began targeting issues such as administrative inefficiency, racial discrimination, excessive taxation, and even the hypocrisy of Indian elites who emulated their British rulers. (Bhattacharya, 2019)

Notably, Indian cartoonists did not only copy Western styles but also localized them. They used visual cues that were borrowed from folk culture, religious iconography, and local dress. The traditional turbans, curled mustaches, and anglicized Indian clerks, for example, became visual clichés, which were used to satirize the colonizers and the collaborators. Bhattacharya points out that this localization was necessary: it rendered the satire understandable and accessible to Indian readers, many of whom were newly literate and hungry to engage with political thought through imagery instead of thick prose. Regional diversity of this satirical movement also needs mention. Oudh Punch, which was based in Lucknow, Bengali magazines like Basantak and Bharat Mihir began depicting with caricatures their denunciation of both British dominance and the Bengal Renaissance intelligentsia. The art form of caricature, although originally imported, soon came to speak in multiple Indian languages, both visually and verbally.

Caricature as Subversive Commentary on the Raj

These caricatures served as “coded commentaries,” handy in a political environment where censorship hung heavy. In this context, caricature served not only as imitation of British satire but as a subversive reworking, reappropriating colonial visual idioms to satirize colonial power itself. The colonial rulers, who were once so proud of their Punch-inspired media, became its objects of mockery in Indian versions shortly. Indian cartoonists soon adapted the material, aiming at British administrators, Indian elites, and social problems with a sophisticated and culturally informed sense of humor. (Chopra, 2018)

The inefficiencies, absurdities, and racial arrogance of the British official class. These caricatures tended to stereotype the physical features of the British officials: bulging eyes, large noses, awkward poses highlighting their foreign presence and humorous disconnection from Indian realities. Cartoons represent the British collector as befuddled, alienated from the indigenous population, or fixated on procedure to the exclusion of human pain. The act itself of reducing colonial power to caricature, making it foolish and ridicule-worthy, was itself an extremely political action. Cartoons permitted Indians to recover power in the domain of perception, where the great colonial icon could be mocked without retribution. Colonial caricatures also exposed the underlying racial architecture of the British Empire, frequently satirizing the obvious double standards exercised over Indian subjects.

Described by Virien Chopra as “civilizing the natives,” it is empty and hypocritical. For instance, some cartoons juxtaposed British insensitivity to famine or injustice in India with their congratulatory orations in London. By employing humor to expose the contradictions of imperial ideology, cartoonists encouraged readers to see colonial power not as benevolent rule but as a system of domination masquerading in moral pretensions. In a low-literacy society with strong traditions of visual narrative, such cartoons were crucial to popular political education. Notably, these satirical magazines did not spare the Indian elite either. Westernized Indians who adopted British manners or advocated colonial policies for self-benefit were also targeted by caricaturists. The “babu” trope a ridiculously over-educated, ineffective Indian clerk who aped British mannerisms became a caricatured stock figure, frequently depicted as pompous, self-absorbed, and culturally perplexed. By doing so, caricatures not only challenged outside colonial authority but also chastised inside complicities and class divisions.

Representations, Stereotypes, and Public Imagination

One of the most intriguing elements of colonial Indian caricature is its initial struggle to personify the masses, an arduous task within a hierarchical and heterogeneous society. Indian cartoonists started to formulate symbolic characters capable of representing the collective experience of colonial domination. Whether it was the “native gentleman” torn between Western education and Indian tradition, or the oppressed peasant victim of double exploitation by the colonial administration and the local landlord these representations bore a double burden: they had to be particular enough to call up recognition, and general enough to stand for a class or caste experience. Typically, this symbolic “common man” was depicted as passive, wide-eyed, and awed someone onto whom the abuses of empire and society could be projected. The caricature’s visual language depends heavily on exaggeration and in colonial India, this involved reinforcing (and sometimes subverting) social stereotypes.

The babu, easily the most emblematic figure in early Indian satire, was a target of constant ridicule. Usually depicted as effeminate, verbose, excessively anglicized, and totally disconnected from the “real India,” the babu was a satirical symbol of India’s English-educated middle class stuck uncomfortably between their colonizers and their traditions. The criticisms were closely in line with early nationalist and socialist ideologies, which aimed to construct a new vision of India free from foreign and feudal exploitation. The zamindar’s bloated rotund shape and gold-encrusted finery were contrasted with the gaunt peasant, a visual juxtaposition that served to make the economic contrast more sharply apparent. What makes these images so effective is not only their humor but their emotional economy, the capacity of one cartoon to induce laughter, outrage, and recognition simultaneously. Cartoons during this time often reflected the mundane contradictions of a transitional society: Indians learning to navigate courts and bureaucracy, wrestling between Western modernity and traditional morality, or critiquing the foreign rulers while maintaining internal hierarchies.

periodicals served as “sites of cultural negotiation,” where various identities colonial, national, regional, and religious were in constant dialogue and frequently in conflict. The man on the street in ink was now a symbolic easel, where cartoonists could play out these tensions with complexity, irony, and humor. (chopra, 2018)

Caricature in colonial India was not only an art form; it was a representation of the contradictions and changing consciousness of a colonized society. Colonial mimicry was transformed into creative dissent by Indian cartoonists, employing local idioms to voice resistance. These images exposed the hypocrisies of British rulers and Indian elites, inventing symbols for the common man to be heard and seen. Interweaving humor and criticism, caricature was a visual language of protest, creating political consciousness in a still illiterate but visually literate society. These cartoons were ultimately at the center of creating a politically engaged public imagination. With ink and irony, colonial Indian caricaturists painted an empire in decay and a nascent nation.

References

(Bhattacharya, D. 2019) Caricature in Print Media: A Historical Study of Political Cartoons in Colonial India (1872-1947)

(Chopra, V. no date) Cartoons in the Raj; A study of the illustrated periodicals of Colonial India.

- September 4, 2023

- 6 Min Read

- August 28, 2023

- 6 Min Read