Jade’s Royal Touch: A Deep Dive into Mughal Art and Culture

Article By – Dixha Negi

The Mughal era represents a golden age of jade craftsmanship in India. The exquisite beauty, technical mastery, and cultural significance of Mughal jade objects continue to inspire and captivate viewers around the world.

One would usually associate the term jade stones and objects with the Chinese empire. This is not surprising, as jade has been an article of religious significance for the Chinese, for centuries. Being of religious significance and funerary rituals, it is reasonable for us to assume that every person, must’ve aspired to possess objects, irrespective of their economic status. But due to the administrative hierarchy of the Chinese Empire, it was only accessible to men of higher socio-economic standings. Interestingly, very few people realize that India too has very rich tradition of carved jade and this is all thanks to the Mughals.

The Mughals, with their Central Asian roots, inherited a deep appreciation for jade from their Timurid ancestors. This beautiful green stone, known for its durability, vibrant colours, and intricate carving possibilities, became a symbol of their imperial power and refined taste. Interestingly enough, jade isn’t actually a single mineral but rather two distinct ones: Jadeite and Nephrite. While both are highly valued for their beauty and hardness, they differ in their chemical composition and physical properties.

THE HISTORICAL ROOTS OF JADE IN INDIA

But the historical significance of jade in India extends far beyond the Mughal era. Evidence suggests that its use dates back to the Indus Valley Civilization, with jadeite beads discovered at prominent sites like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. This also highlights appreciation for jade’s beauty and durability. The earliest literary reference to jade in India can be traced to the 7th century CE, when the Chinese traveller Hsuan Tsang described a remarkable 8-foot-high Buddha statue crafted from blue jade in the region of Samatata, located in present-day Bengal.

The rich history of jade in India continues to unfold with discoveries and references from various regions and periods. Kolanapaka Jain temple of Telangana, estimated to be over a thousand years old, houses the idols of three Jain Tirthankara: Lord Adinath, Lord Neminath and Lord Mahavir. The figure of Lord Mahavir, standing tall at over four feet, is carved from jade and believed to date back to the temple’s founding in the 11th century CE. Moving forward to the Delhi Sultanate period, we encounter a few surviving jade objects that offer glimpses into the Islamic cultural influence on jade craftsmanship in India. The miniature Quran stand, dated to 1209-10 and once owned by Iltutmish, a ruler of the Delhi Sultanate’s Slave Dynasty, is one such exquisite piece, currently on display at the Salarjung Museum in Hyderabad.

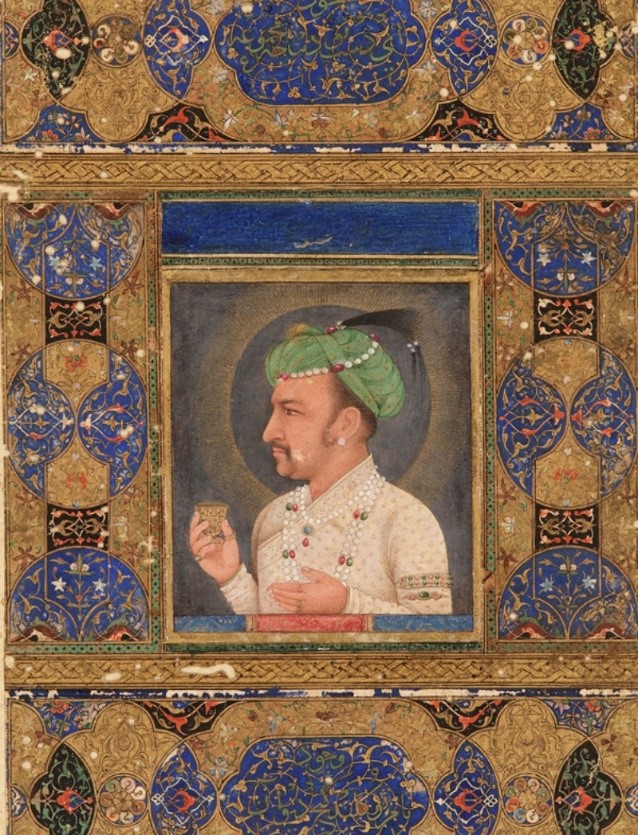

The French physician François Bernier during his travels to Kashmir with the court entourage of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707), observes in a letter written in 1665 the high value placed on jade by Mughal emperors. The Mughal jade workings began under Emperor Akbar (1556-1605) but flourished under the reign of Emperors Jahangir (1605-1627) and Shah Jahan (1628-1658), both known for their refined aesthetic tastes in art. Emperor Jahangir’s interest, in particular, is evident from the surviving artifacts; a number of surviving jade drinking vessels engraved with his name and imperial titles. This is also evident in the portrait depicting Jahangir holding a white jade wine cup emphasize its significance as a royal attribute. It must be remembered well that jade was associated with purity, longevity, and power, making it a fitting material for royal artifacts. It also possessed the ability to neutralize poisons, which led to its use in creating drinking vessels and other utilitarian objects.

The Mughals’ fascination with jade was deeply intertwined with their Timurid heritage. By patronizing jade craftsmanship, they not only honoured their ancestral connection but also solidified their own imperial identity. The jade used in Mughal artifacts was primarily nephrite, sourced from regions like Burma, Tibet, and Kashgar in present-day China. This choice of material further emphasized the Mughals’ Central Asian roots and their access to valuable resources from across the Silk Road.

Figure 1: Portrait of Emperor Jahangir holding wine cup. (Source: Map Academy)

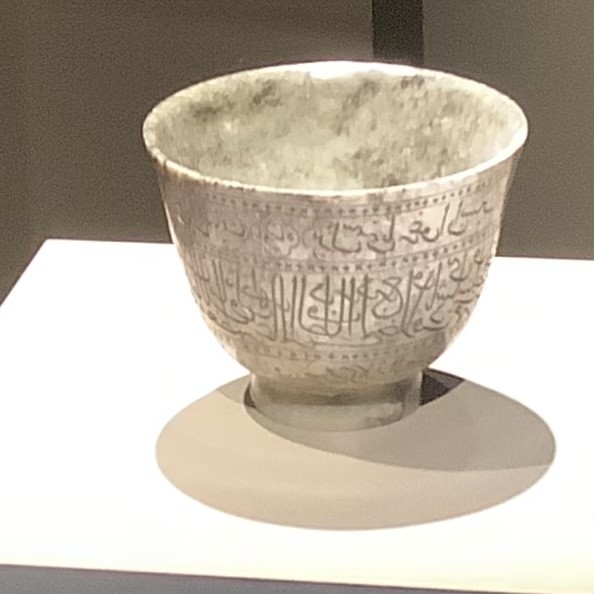

Figure 2: Jahangir’s wine cup (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

THE AESTHETIC AND TECHNICAL MASTERY

While the aesthetic appeal of Mughal jades is widely recognized, the specific techniques and tools used to craft these masterpieces have been less explored. While direct documentation of Mughal jade workshops is scarce, insights can be gleaned from contemporaneous and later sources.

The primary tool employed in jade carving was the bow lathe, a versatile device that could be used for shaping, grinding, and polishing the hard stone. Lapidaries would use abrasive materials, such as emery or corundum, to gradually remove material and refine the desired form. The final step involved polishing the jade to a high lustre, often using finer abrasives and water.

Beyond their decorative appeal, Mughal jades often exhibit remarkable sculptural qualities. The artisans who crafted these objects possessed a deep understanding of the material’s properties and limitations. They skilfully manipulated the stone, creating intricate details and subtle nuances of form and texture. The interplay of light and shadow on the polished surfaces highlights the sculptural qualities of these objects, creating a mesmerizing visual experience.

The A’in-i Akbari, a monumental work by Abu’l Fazl, provides one of the earliest literary glimpses into the world of Mughal lapidary arts. Abu’l Fazl, Prime Minister during Akhbar’s reign, distinguishes a particular type of jeweller known as the “Zarnishan,” who specialized in cutting and setting various gemstones, including agate, crystal, and jade. These skilled artisans were responsible for embellishing and engraving stones, showcasing their mastery in shaping and manipulating these precious materials.

TYPES OF MUGHAL JADE OBJECTS

The vast body of Mughal jade work showcases a wide range of artistic quality, reflecting the varying levels of patronage and skill over centuries. However, the finest examples stand as pinnacles of artistic achievement, demonstrating exceptional mastery of form and aesthetic expression. Mughal jade objects can be broadly categorized into three main types: ceremonial arms and martial accessories, decorative objects and accessories, and utensils and storage objects. Each category showcases the exquisite craftsmanship and artistic flair of the Mughal era.

CEREMONIAL ARMS AND MARTIAL ACCESSORIES

Ceremonial arms and martial accessories were often crafted from jade, symbolizing power, prestige, and the martial spirit of the Mughal rulers. These objects, though not intended for actual combat, served as symbols of authority and were often displayed in royal armouries or presented as gifts to dignitaries.

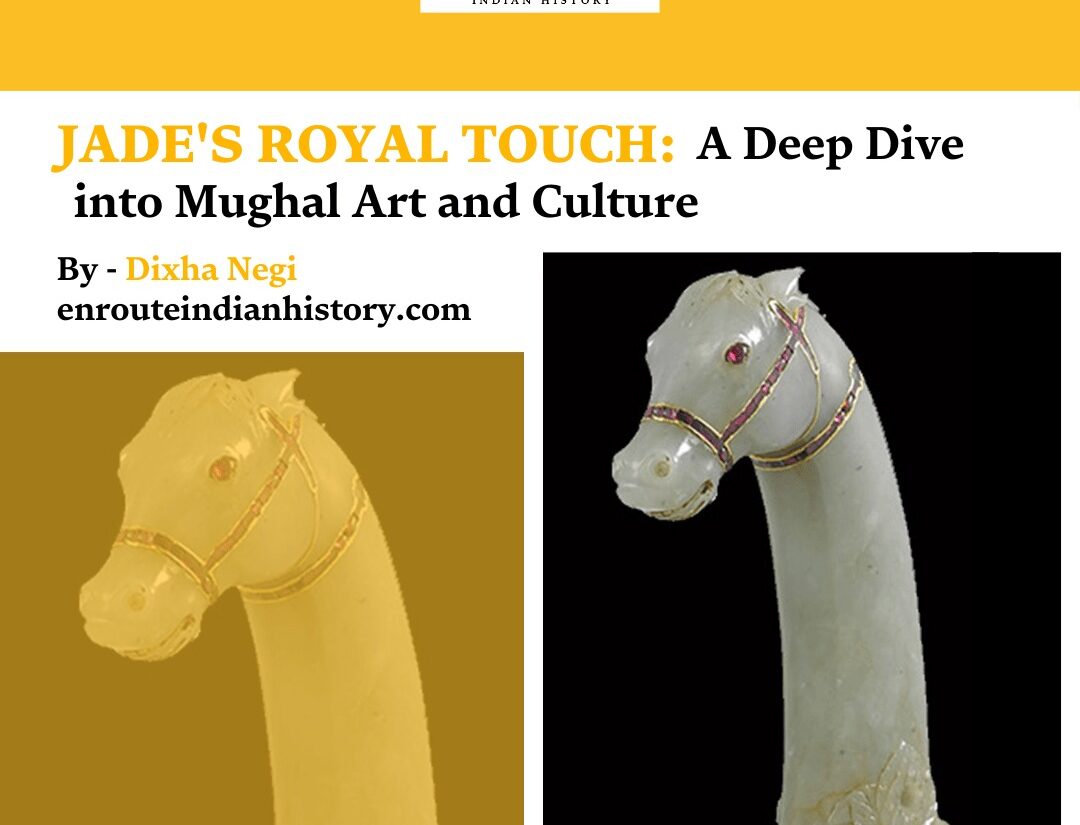

One such masterpiece, now housed in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is a dagger hilt in the form of a horse’s head. This exquisite piece, carved from aqua green jade with burnt-orange accents for the mane, showcases the pinnacle of Mughal jade carving. The inscription on the blade, in gold damascene, reveals that this dagger was the personal possession of Emperor Aurangzeb, dating back to 1660/61. The royal parasol depicted on the blade further underscores its imperial provenance.

The horse’s head depicted on the dagger hilt is a remarkable feat of artistic skill. The lapidary has meticulously captured the distinctive features of an Arabian stallion, a breed highly prized by the Mughals for its beauty, speed, and endurance. The concave facial profile, convex forehead, small muzzle, large expressive eyes, and short, inward-curving ears are all hallmarks of the Arabian breed. By accurately portraying the physical attributes of the Arabian horse, the artist has elevated the dagger hilt to a work of art that transcends its functional purpose. It serves as a testament to the high level of craftsmanship and artistic sophistication achieved during the Mughal era.

The lapidary’s depiction of the horse not only showcases its physical attributes but also imbues it with a sense of martial spirit, fitting for a ruler like Aurangzeb, known for his military campaigns. The horse’s posture, with its ears laid back, flared nostrils, and bared teeth, conveys a sense of readiness and aggression, reflecting the emperor’s warrior persona.

The attention to detail in the Aurangzeb dagger hilt is truly remarkable. The naturalistic treatment of the horse’s neck and throat, with the delicately rendered mane and the ergonomic design for a comfortable grip, demonstrates the lapidary’s deep understanding of both equine anatomy and human ergonomics. Furthermore, the Mughal influence is evident in the decorative elements, such as the split acanthus leaves and tulip motif. These motifs, often found in Mughal architecture and other art forms, add a touch of elegance and sophistication to the dagger hilt.

Figure 3: The hilt of green nephrite in the form of a horse’s head set with rubies in gold (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

UTENSILS AND STORAGE OBJECTS

Jade was also used to create a variety of utensils and storage objects. These items were often used for personal use or as gifts to high-ranking officials. This preference was not merely aesthetic but also rooted in the belief that jade possessed protective qualities, particularly against poisons.

The Mughal treasury, as described by the English merchant William Hawkins, boasted an impressive collection of jade drinking cups, among other precious objects. This highlights the high esteem in which jade was held by the Mughal rulers. Mughal jade artisans employed various techniques to enhance the beauty and value of their creations. Some pieces were adorned with gold paint, precious stones like lapis lazuli, diamonds, rubies, and emeralds, or intricate enamelwork. Others, however, were left unadorned, relying solely on the natural beauty and intricate carving of the jade itself.

The jade bowl in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is a prime example of the sensuous tactile appeal that characterizes the finest Mughal jades. Carved from mottled dark green nephrite, this elegant bowl possesses a graceful form with a flared lip and two scrolled acanthus leaf handles. The low foot, adorned with overlapping lotus leaves, adds a delicate touch to the overall design. When viewed with transmitted light, the bowl takes on an ethereal quality, highlighting the translucency of the jade and the subtlety of its carving.

Figure 4: Jade bowl made from mottled dark green nephrite (Source: Asian Art)

DECORATIVE OBJECTS AND ACCESSORIES

Mughal artisans also used jade to create a wide range of decorative objects and accessories. These items were often intended for personal use or as gifts for members of the royal court. The Mughal era, particularly the 16th and 17th centuries, saw a flourishing of artistic and cultural expression. While jade was undoubtedly valued and used in various forms, it was not as highly prized as other materials like precious stones and gold. As a result, we encounter fewer jade jewellery pieces and more decorative objects like mirrors, jars, boxes, and containers.

Mirrors, introduced to the Mughal court in the early 16th century, were initially seen as exotic curiosities. Over time, they evolved into luxurious objects, often framed in ornate jade and backed with the same material. One such exquisite example is a leaf-shaped mirror adorned with a blossoming plant on its back. This piece embodies the pinnacle of Mughal craftsmanship, showcasing the intricate carving and delicate design characteristic of the period.

The Mughal era witnessed a flourishing of jade craftsmanship, with artisans creating a diverse range of objects, from functional items to decorative pieces. These objects were often adorned with gold paint, precious and semi-precious stones, or intricate enamel work. Others, however, were left bare, relying solely on the natural beauty and intricate carving of the jade itself.

Floral and animal motifs were popular in Mughal jade designs. The acanthus and chrysanthemum were common floral motifs, while the horse, often symbolizing power and prestige, was a frequent animal motif.

Figure 5: Jade Mirror in the Form of a Leaf (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

THE ENDURING LEGACY OF MUGHAL JADE

While the Mughal emperors following Jahangir and Shah Jahan continued to patronize jade craftsmanship, the quality and innovation of the earlier period remained unmatched. Some contemporary and successor states, such as the Rajput and Deccani kingdoms, also produced jade objects, but it was not until the 19th and 20th centuries, under the Nizams of Hyderabad, that we see significant collections of jade, many of which were of Mughal origin.

Today, Mughal jade objects can be admired in renowned museums worldwide, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Louvre Museum, the British Museum and the Victoria Museum, and in India, at the National Museum and the Salarjung Museum in Delhi and Hyderabad respectively. These institutions house some of the most significant and impressive collections of Mughal jade, offering a glimpse into the rich artistic heritage of this bygone era.

REFRENCES AND IMAGES

- PeepulTree. (2021). Available at: https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindia/story/art-history/the-romance-of-mughal-jade?srsltid=AfmBOooBZfofBqY2H8-yC-zZ8uzH08cj3-UHSBhz38vTTOxRkBcm6ub9 [Accessed 17 Nov. 2024].

- Asianart.com. (2024). Stephen Markel: Mughal Jades – A Technical and Sculptural Perspective. [online] Available at: https://www.asianart.com/articles/markel2/index.html [Accessed 17 Nov. 2024].

- Internet Archive. (2014). Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656-1668 : Bernier, François, 1620-1688 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. [online] Available at: https://archive.org/details/travelsinmogulem00bernuoft/page/422/mode/2up?q=jade [Accessed 17 Nov. 2024].

- Markel, S. (2004). Non-Imperial Mughal Sources for Jades and Jade Simulants in South Asia. [online] Jewellery Studies 10 (2004): 68-75. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/3759445/Non_Imperial_Mughal_Sources_for_Jades_and_Jade_Simulants_in_South_Asia [Accessed 17 Nov. 2024].

- Mirza, A. (1961). ”MUGHAL JADES AND CRYSTALS; j^A CATALOGUE. [online] Available at: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/33549/1/11010308.pdf [Accessed 17 Nov. 2024].

- Figure 1 from The Emperor and his Wine Cups – MAP Academy

- Figure 2, 3 and 5 from Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)