Evolution, Decline, and Revival of Indian Papermaking throughout the Ages

The advent of papermaking marked a revolutionary leap in technology, reshaping the very fabric of communication and record-keeping throughout the annals of history. Prior to the global ascent of paper, diverse mediums like papyrus, parchment crafted from untanned animal hides, palm leaves, and enduring stone bore the weight of human expression.

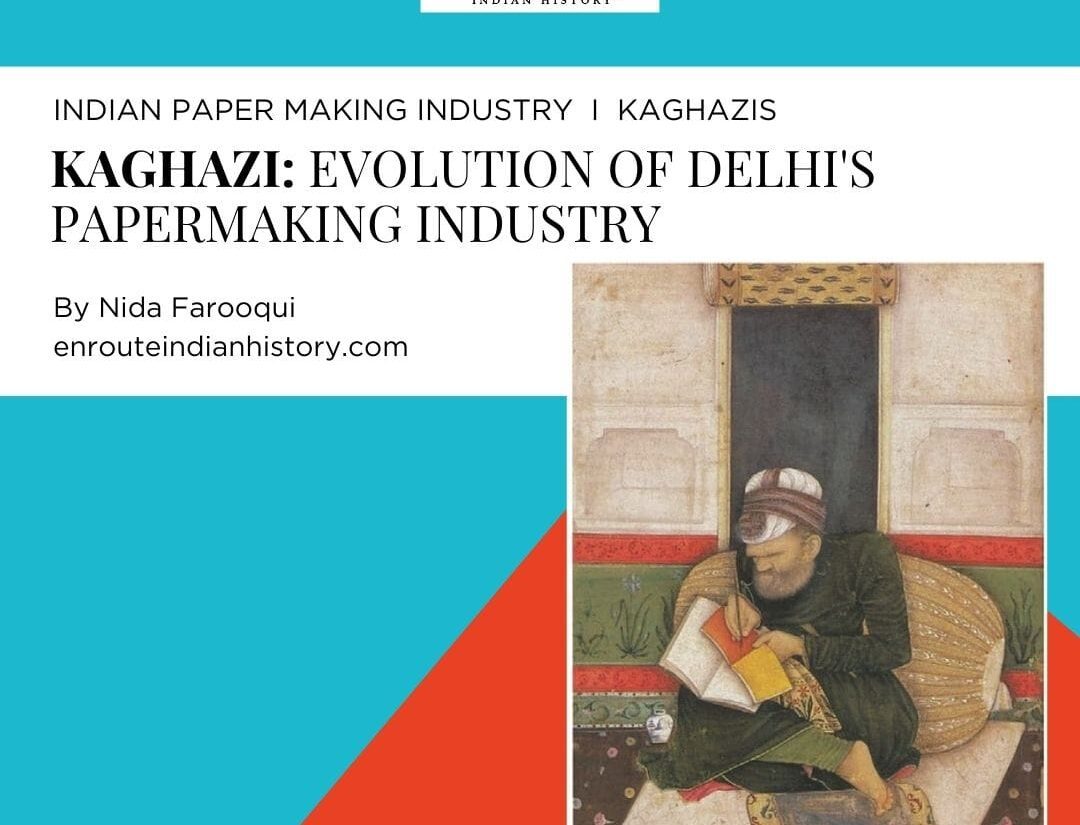

In the Indian narrative, the 15th century witnessed the burgeoning emergence of pivotal centres dedicated to the artistry of handmade paper production. As if choreographed by time itself, paper progressively eclipsed palm leaves and birch bark, solidifying its role as the paramount medium for the transcription of knowledge and stories. At the heart of this metamorphosis were the Kághazis, the custodians of the craft, weaving their expertise into the very fabric of cities and towns across the subcontinent.

These skilled artisans, the Kághazis, transcended mere vocations; they became indispensable pillars within imperial courts, bustling marketplaces, sacred orders, and meticulous record-keeping domains. The evolution of papermaking in India, from its nascent stages to the contemporary era, reflects not just a transformation of materials but a vibrant tapestry of innovation, resilience, and the enduring human quest for connection through the written word.

Harvard University Art Museum ; Painting of an old scribe writing on a paper by Bichitr, 1625.

Traversing Unique Paths – The Creative Arrival of Papermaking in India

Originating in the ancient workshops of China, where papermaking techniques took root between the second century BCE and the third century CE, this transformative craft embarked on an odyssey of westward diffusion.

Around the seventh century CE, the echo of papermaking reached the majestic heights of Tibet, meandering through the rugged landscapes and transcending political boundaries. From Tibet, this artistry cascaded into neighbouring regions, including present-day Nepal, Bhutan, and the Himalayan fringes of India. In these diverse terrains, a fascinating narrative of papermaking unfolded, revealing not only a technological exchange but a nuanced interplay of materials and methodologies.

Distinctive in its composition, the papers of Nepal and the Himalayan regions stood apart. Fashioned from the fibrous bark of the lokta (daphne) bush, they distinguished themselves from their Indian counterparts, where rags, tát, or hemp (san) were the predominant sources.

Kathmandu Valley Co. ; A letter from Tibetan Governor to a Nepalese official written on lokta paper c. 1887.

A pivotal moment in the evolution of South Asian paper production unfolded during the 15th century, marked by the establishment of a flourishing papermaking industry in Kashmir. At the helm of this transformative period was the Sultan of Kashmir, Zain ul-Abidin, reigning from 1418 to 1470. The Sultan, credited with the ascendance of the Kashmiri papermaking trade, is said to have summoned skilled artisans from Samarkand in Central Asia to his court. These artisans were granted significant jagirs (land entitlements) to establish themselves in Kashmir, where they were actively encouraged to develop a robust production industry. George Forester, who arrived during the Afghan rule, attested to Kashmir’s prowess in papermaking, noting, “Kashmir fabricated the best writing paper of the land, and that it was an article of extensive traffic.” The region, with its strategic support and cultivation incentives, not only became a haven for these artisans but also earned renown for producing exceptional quality writing paper that became a sought-after commodity in trade.This strategic move not only enriched the cultural fabric of Kashmir but also firmly intertwined the region with the artistry and significance of paper production.Kashmir played a vital role as a supplier of handmade papers to writers in various Indian states. The industry comprised two units—one in Ganderbal and another in Nowshera, an area within the Srinagar district. These units reportedly remained operational until the later period of Dogra rule. Interestingly, the locality of Nowshera, where these papermaking units were established, has retained its historical significance, now recognized as Kazgari Pur or Kazgari Mohalla, preserving the legacy of this once-flourishing industry.

Islamic Art and Architecture, Pinterest ; Drawing depicting Chinese paper makers in Samarqand.

The prestige of Kashmiri paper endured prominently across South Asia until the early 20th century. Various communities engaged in paper production throughout the subcontinent often asserted a lineage of learning the craft from Kashmiris, framing their practices as a means to enhance their economic standing. Alternatively, some papermakers underscored their historical ties to dynastic patronage. For instance, those in Sialkot, located in present-day Pakistani Punjab, traced their papermaking traditions back to Kashmir and enjoyed substantial support under the Mughal ruler Jahangir. In Rajasthan, the establishment of a notable papermaking community in Sanager is commonly linked to Raja Man Singh, the Rajput Mughal official. Simultaneously, the renowned papermaking town of Junnar in Maharashtra is said to have garnered support from the Marathas.

Throughout South Asia, the majority of papermakers were Muslims. This prominence within the craft might be attributed to the historical association between paper use and production in India and the expansion of Muslim dynasties. Some papermakers even asserted that their presence in certain regions coincided with the expansion of influential dynasties such as the Mughals. As these communities proliferated and evolved across the subcontinent, their craftsmanship became renowned through variations of the Persian word “kághaz” (paper). This term, adapted into various forms, such as “kágaj” or “kágad,” found resonance in a diverse array of Indian languages, including Punjabi, Marathi, Bengali, and Kannada.

South Asian kághazis not only crafted paper using traditional materials like tát (hemp or san) and rags but also delved into innovative experiments with pulps and papermaking technologies. This exploration yielded new, often delicate, and highly prized varieties of paper.

In the mid-20th-century Punjab, another Indian method of handmade paper production was prevalent. In this process, tat or gunny cloth underwent manual cutting, followed by moistening and pounding. After this initial treatment, the material was washed and shaped into square cakes by incorporating an acid. These cakes were then left to dry, subsequently pounded and washed again. The next steps involved mixing the material with water, a continuous stirring process with bamboo sticks, and the preparation of the pulp for straining. The papermaker skillfully caught a fine layer of pulp on the strainer, forming a sheet of paper once the water was strained off. The final stages included polishing the paper, making it ready for various purposes.

1001 Inventions ; A 17th century manuscript depicting the paper – making process.

Lawrence offers a concise portrayal of the papermaking process in Kashmir. According to his account, the pulp is placed in stone troughs or baths and blended with water. From this amalgamation, a layer of pulp is extracted onto a lightweight surface and left to dry in the sun. Subsequently, the dried paper undergoes a polishing process using pumice stone, followed by the application of rice water to glaze its surface. A final polishing touch with stone concludes the process, leaving the paper ready for use.

The Ebb of Indian Papermaking: Colonial Impact and Industry Decline

Unfortunately, with the advent of colonial rule in India, the Indian papermakers started facing some severe challenges in this trade and manufacturing of paper. They were challenged by the mechanised paper mills installed by the European authorities in India. The inception of mechanised paper mills in India traces back to the early 19th century when European settlers pioneered their development in Bengal. The first successful ventures in the region took root in the 1860s with the establishment of mills in Bombay and Calcutta. By the early 1880s, India boasted six operational private mechanised paper mills, with three situated in the Bombay presidency, one near Calcutta in Bally, one in Lucknow, and another in Gwalior. The expansion continued with the inauguration of a seventh mill at Titaghur near Calcutta in 1884. This marked a transformative phase in the history of Indian papermaking, transitioning from traditional methods to mechanised production.

During this era, Indian papermakers encountered an even more formidable challenge—the looming threat of imported paper. Despite the establishment of seven mills in India by 1885, the volume of paper produced domestically still paled in comparison to the substantial quantities imported from Europe.

Adding to the complexity, handmade papermaking communities found themselves contending with the emergence of a significant new player in the industry: colonial jails.Starting from the 1830s, British directors in India applied jail labour schemes to each area and managed Indian convicts.. This move not only altered the landscape of handmade paper production but also introduced a formidable competitor to traditional artisans.

In Sialkot, a bastion of renowned papermaking, the kághazis faced formidable competition and pressure from the rise of prison paper production. To counter these threats, they strategically emphasised the superior quality and strength of their paper in contrast to the products manufactured in prisons. Dard Hunter, a distinguished American scholar of papermaking, underscored the excellence of Sialkot paper, noting that “none [of the jails], with all their resources, have improved on the best Sialkot stuff.”

While other kághazis tried to form partnerships with the burgeoning publishing houses across India. This strategic move aimed to secure a consistent demand for their products. Some kághazis adopted cost-saving measures by altering the materials used, allowing them to competitively price their papers against those produced by jails and mills. A notable shift involved the incorporation of scrap paper into their pulps, showcasing a commitment to recycling and economic viability in the face of changing industry dynamics.

In the early 20th century, certain groups were determined to revive and safeguard Indian handmade papermaking, particularly following the emergence of the swadeshi movement. Recognizing the potential of papermaking as a cottage industry that could underpin an independent Indian economy, Mahatma Gandhi lauded it alongside other trades. A key advocate for this cause was K.B. Joshi.

In the early 1940s, Joshi articulated a transformative vision, stating that “the manufacture of paper by villagers in India will not fail to revolutionise their economics.” With the backing of Gandhi, Joshi established a Handmade Paper Institute in Pune in 1940. This institute aimed not only to preserve regional paper traditions but also to introduce new materials and practices, making handmade paper competitive in the Indian market. The initiative sought to intertwine economic self-sufficiency with the preservation of cultural heritage.

In tracing the intricate journey of the Indian papermaking industry through the lens of the Kághazis, we navigate a narrative marked by evolution, resilience, and transformation. From the ancient roots of handmade paper production, we witness its flourishing during the 15th-century Kashmiri renaissance, its encounter with colonial challenges, and the subsequent rise of mechanised mills in the 19th century. Despite the looming threats posed by imported paper and the emergence of colonial jail-based production, the Kághazis demonstrated remarkable tenacity. It is a story of adaptability, where tradition meets innovation, and artisanal craftsmanship intertwines with economic resilience. From the bustling centres of medieval Kashmir to the halls of colonial jails and the cottage industries envisioned by Gandhi, the Kághazi narrative serves as a testament to the enduring spirit of a craft that has not just weathered transitions but continues to inscribe the story of a nation on its versatile, handmade pages.

References

- Teijgeler, Rene & Teygeler, René. (2001). Handmade paper from India: Kagaj yesterday, today and tomorrow. 10.13140/2.1.1499.5522.

- “The Kághazis’ Story: How the Indian Papermaking Industry Evolved, Declined and Transformed.” 2023. The Wire. https://thewire.in/history/kaghazis-india-papermaking-industry.

- Ahmad, Iqbal. 2018. “The forgotten art of Paper making.” Kashmir Images Newspaper. https://thekashmirimages.com/2018/11/25/the-forgotten-art-of-paper-making/.

- “The Rise of an Industry: Papermaking – 1001 Inventions.” n.d. 1001 Inventions. Accessed November 26, 2023. https://www.1001inventions.com/paper/.

- February 22, 2024

- 8 Min Read