Law in the Everyday: A History of the Salt Tax

- enrouteI

- June 27, 2023

Salt is a commodity that we now take for granted. No one bats an eye to its presence: it’s just there in stores, kitchens, and on our plates, as it is supposed to be. Salt is crucial for human existence due to its nutritional value due to its chemical composition:Sodium ions are necessary to perform basic biological tasks. What rarely crosses our minds, however, is that as mundane a commodity as salt may be, it has played a role in propping up empires and engendering resistance to them. There is remarkable continuity in how empires and later national governments have maintained their authority on salt, its production, circulation, and consumption.

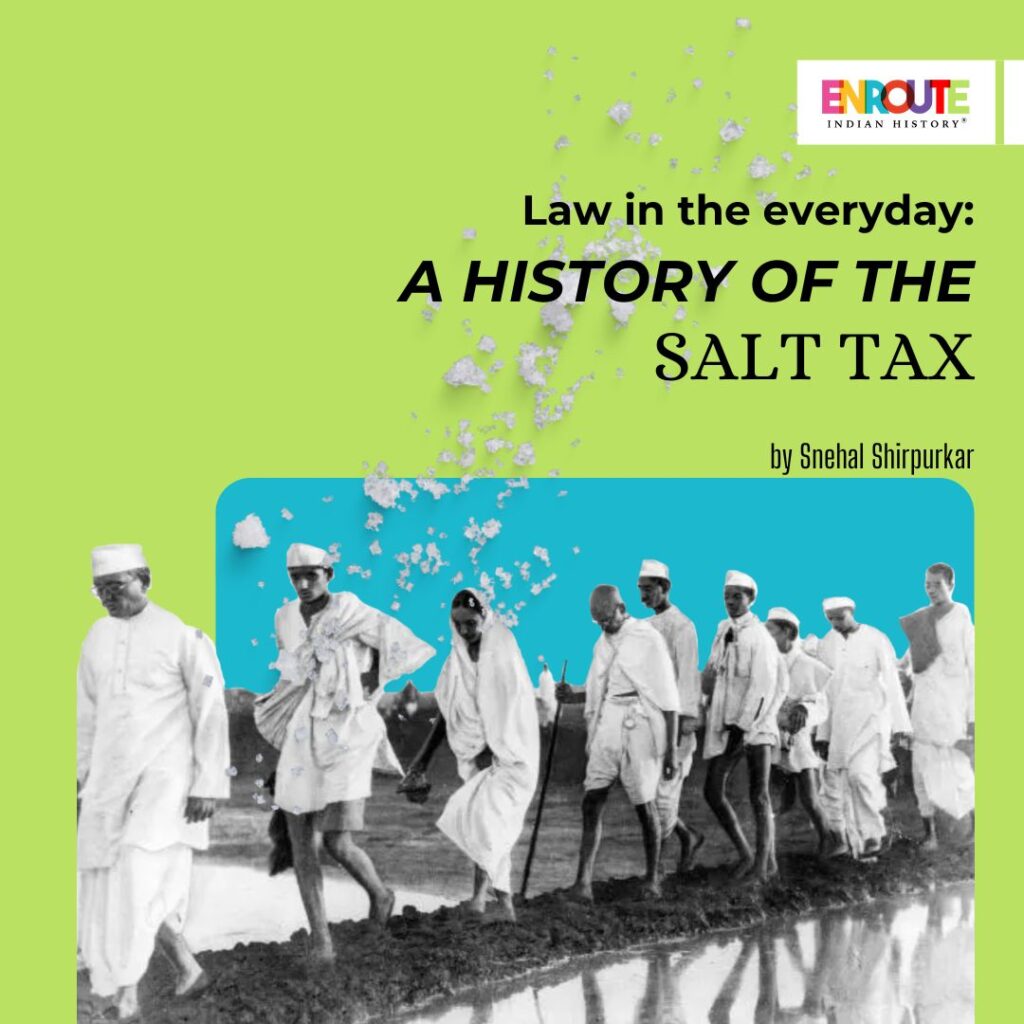

Salt has historically been a subject of law. This stretches back to the beginnings of British rule in the 1760s and later, through another law that became a hallmark of Gandhi’s freedom struggle. The history of the salt tax, however, does not end with Gandhi’s Dandi March (1930). The Salt Act of 1944 combined pre-existing laws with continued application of older laws to existing salt factories, with the Central Excise Act of 1944 covered taxation on salt’s production and sale. The laws were scrapped when India became independent in 1947, only to resume in 1953. The laws continued to remain in place until as recent as 2016, when the Goods and Services Tax was implemented. The Goods and Services Act does not include salt as a taxable commodity.

Table salt continues to be taxed in Pakistan. Why would such salt laws, ones rooted so strongly and so visibly in British colonial authority continue in the 21st century; and what can their persistence tell us about laws in a post-colonial nation?

In 1765, Robert Clive granted a total monopoly to the East India Company’s servants in the making and sale of salt.

The production of salt by other entities was declared illegal. Hastings went on to reinstate this monopoly in 1780, after a brief spell when the Exclusive Company was forced to relinquish its monopoly. A large portion of the wholesale price of salt went to the Company as tax. It remained at an extraordinary level throughout the late 18th and until the late 19th centuries. A customs line stretching across India, with armed guards and checkpoints, was established to prohibit salt trafficking from other parts of India into the Bombay, Bengal and Madras Presidencies. The Transport of Salt Act (1879) sought to restrict the transport of salt by sea along the western coast, imposing penalties of a thousand rupees or imprisonment to those caught violating it. The Bengal Salt Act of 1838, the Madras Salt Act (1884) and the Bombay Salt Act (1890) and the Indian Salt Act of 1882, all overlapping in content and bearing heavy similarities operated to regulate the production, consumption, export, and prevent smuggling of salt regionally. The salt monopoly also allowed the British to import and English salt in the country.

Considering all of these laws that centered salt, it comes as no surprise then that salt was of immense importance to British control. Salt was crucial for the British treasury in material terms. By the time of the Civil Disobedience in the 1930s, the Salt Tax amounted to £25,000,000 out of total revenue of about £800,000,000. Salt was an essential commodity, in levying tax on it and controlling consumption, it also wielded symbolic power. The salt deprivation caused by these laws led to increased prevalence of leprosy and exacerbated the famines during this period. Considered thus, the tax can be seen as a symbol of the brute British force. This symbolism of salt is what Gandhi and other leaders of the Congress picked up on, and salt became the rallying cry for the resistance against the British.

The salt tax was abolished by the Interim Government of India in October 1946. In the Indian constitution, salt is one of the items on the Union list, placing the responsibility of the Manufacture, supply, and distribution of salt onto the central government. Six years post-Independence in 1953, the Salt Cess Act was passed. The revenues raised through this were meant to finance the government-owned and operated entities involved in the production and distribution of salt—the whole set bearing uncanny similarities to the country’s colonial past.

This tax continued to be imposed at a rate of 14 paisa per 40 kg. The total cess collected in the financial year 2013-14 amounted to Rs. 3.3 crores, while the costs associated with collecting it totaled 1.5 crores, nearly 50% of the collection. This pattern can be observed throughout the early 2000s. The high transaction costs associated with its collection ultimately prompted a reevaluation. Common salt is no longer taxable under the Goods and Services Tax (GST) Act of 2017. It took nearly two hundred and fifty-two years for salt, a basic necessity to not be taxed in the subcontinent.

As India witnessed an opening up and liberalization of its economy in the 1990s, laws concerning the manufacture of salt also changed. Salt industries were de-licensed. Now, 92 percent of salt manufacturing units are privately owned. In this shift to private ownership, it appears that salt has mirrored the nation’s trajectory in more ways than one.

Perhaps next time you look at a salt shaker on the dining table, think of the immensely complicated histories behind the seemingly innocent grains. Salt has the force of diets, bodies, and survival behind it, and perhaps that is why it has been so strongly been occupying the minds of lawmakers all this while. To think that we were paying a salt cess, not unlike the one Gandhi protested against all those years ago compels one to think of the continuities between the colonial and the post-colonial that underpin legal and political frameworks, and salt is but one tiny example of these continuities. A look at the history of salt also makes it crystal clear that the law is not as removed from the everyday as we might wish it were. From the Indian Salt Act of 1882 to the Salt Cess Act of 1952, and finally to the GST Act 2017, it has been right there on your dining table.

- April 18, 2024

- 5 Min Read

- April 18, 2024

- 7 Min Read