Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Mumtaz Mohiuddin

On August 14-15, 1947, as India gained independence, it resulted in the subsequent Partition of the nation into two independent states: India and Pakistan. This line of division resulted in the forced mass migration that separated millions along religious lines. It triggered a period of intense violence and loss of life whose stains have stayed with us. When the lines were drawn, and people were divided, perhaps it was assumed that the conflict would be resolved. But what about certain common entities, shared legacies, culture, history, and heritage? How could that legacy be divided?

After the partition, the excavated antiquities and relics were also sought to be equally divided between the two countries under the Partition Council’s official agreement in the 1950s. Officers involved in partitioning India had to take stock of everything: from a ceiling fan to a board pin and then determine what should go to which side. Certain “institutions’ were shared jointly, as were the joint currencies, which certainly held the promise of a future of cooperation. But overall, there was chaos and confusion while dividing men and materials. One special case is that of the British era, the gold-plated, horse-drawn buggy which belonged to the Viceroy of India. Soon after Partition, India and Pakistan claimed the fancy buggy, whose ownership was to be decided by tossing a coin. Sounds unbelievable, right? But Guess what, this is real, India won the toss, and the buggy has remained in India since then, often called the “presidential buggy’.

In the process of dividing assets, animals, too, were supposed to be divided. A fascinating case was of Joymoni, an elephant who belonged to the Forest Department of colonial Bengal. Since there was only one Jaymoni, his value was determined as equivalent to that of a station wagon used by the Land Records and Surveys director. Interestingly West Bengal got the vehicle, and East Bengal got the animal. At the time of Partition, Jaymoni was in Mandla town, West Bengal, and had to be taken to the other side of the border. The real dispute rose when the mahout of Joymoni opted for India. Official archives are silent about the ultimate fate of Joymoni. But the dispute was real and it existed!

There were even bizarre problems like this, such as the curious case of ‘60 stranded ducks’. The undivided Agricultural Department under the Suhrwardy government had ordered these birds sometime in 1946, and they cost £250. Amidst the partition chaos, questions were raised about who is going to make such a transaction. And who would get the ducks: the Government of West Bengal or that of East Bengal?

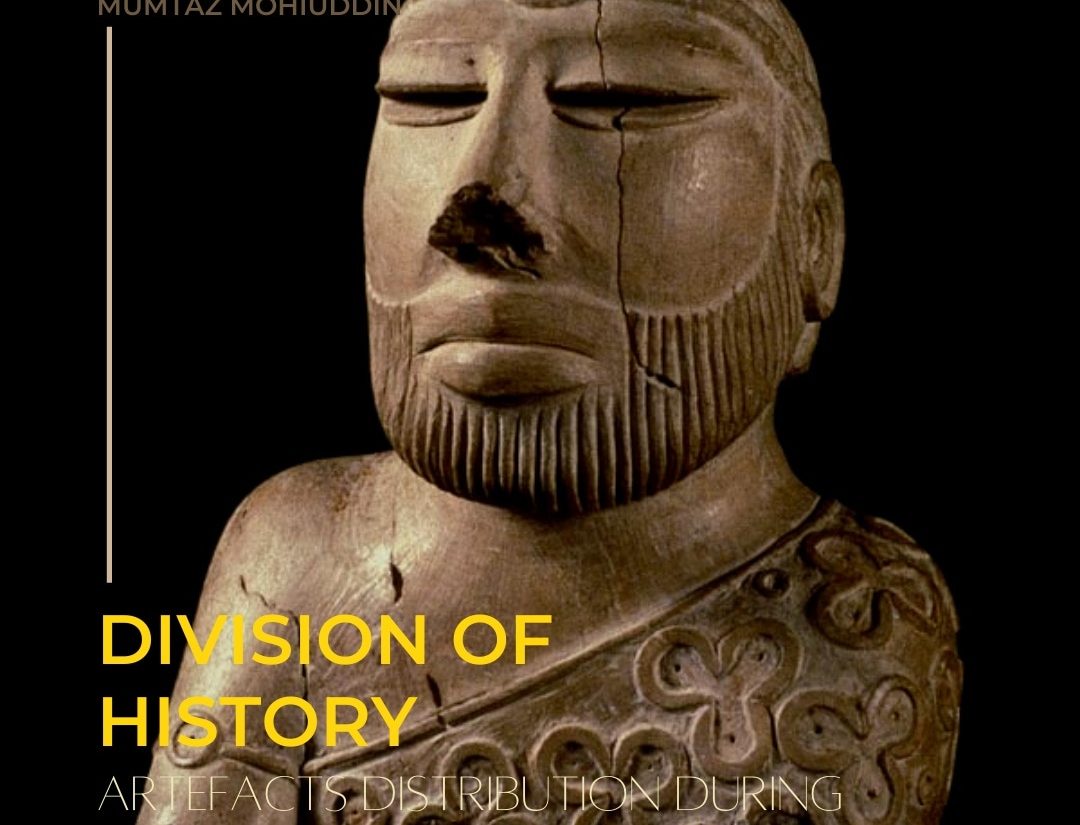

Not only were people, animals, objects, and institutions partitioned, history and heritage too were divided. Pakistan and India fought over the relic and claims over the much celebrated Pre-historic site-The Indus valley civilisation, and each side wanted to claim it on its own since it was no ordinary history. It was a proud past. While the two major sites, Harappa and Mohenjadaro, belonged to present-day Pakistan, India was home to a few other rich sites like Dholavira, Rakhigari, Kalibangan, etc. Some of the interesting relics and artefacts were debated and contested. The question of what was ‘Indian’ and what was ‘Pakistani’ and which one was too ‘unique’ for partition became points of contestation. Each side bargained hard. Certain objects like two gold necklaces from Taxila, one carnelian and copper girdle from Mohenjo-Daro, and a necklace made up of jade beads, and semi-precious stones from Mohenjo-Daro were deliberately fragmented to have a fair share. Thus as Nayanjot Lahiri says, ‘the integrity of these objects were compromised in the name of equitable division.’ Among these, the evacuated ‘bracelet’ from one of the sites of Indus valley was also broken into two pieces – one part was retained in India, and the other went to Pakistan.

Another interesting and recognisable symbol of Harappan artefacts was the ‘Dancing Girl,’ which presently resides in the Indian National Museum. The ‘Chief Priest’ was handed over to Pakistan while the ‘Dancing Girl’ was given to India. The Dancing girl is a 10.5-centimetre high bronze statuette, sculpted using the cire perdue (lost wax method around 2500 BC), a stylistically poised female figure performing dance. It was excavated from Mohenjo-Daro, a site in present-day Pakistan, in 1926. It is a cherished artefact of Indus valley that tells us about the Indus artisans’ knowledge about metal blending and casting and hints at the possibility of Indus society’s cultural evolution in how they participated in dance and other performative arts. However, it has triggered a lot of controversies in the present as to where the dancing girl actually belongs.

The tussle over artefacts shows how the ‘dead’ matter to the ‘living’ more hence continuously revisited often. Similarly, the constant efforts to relate the Indus Valley Civilisation as a part of Vedic culture shows just the modern anxieties emanating from the complex present, which inevitably distorts the past, its history and historical space. Historians and archaeologists of both countries must deal with these complexities and create space and scope for a more nuanced understanding of these issues and concerns so that we find more hopes for a promising future rather than lingering behind a bleak past.

Bibliography

1. Khan, Yasmin. The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, New Haven and London, 2007.

2. Sengupta, Anwesha, Breaking up: Dividing assets between India and Pakistan in times of Partition, Indian Economic & Social History Review • October 2014.

3. https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/2019/03/partition-divided-culture-legacies-artwork-unite/

4. https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/partition-impacted-monuments-newly-formed-india