Source: TGFI, a pile of seven stones and a ball

A yearning follows when we look back at the times, we spent during the breaks we used to get at school – running out to spend those precious minutes, gathering our friends, and rushing to the field. This nostalgia of the old days is a reminder of the excitement we used to feel when the bell rang, soaring through our bodies. Not to say, however, that this childlike essence of those days cannot be returned. All we need to do is remember and safely nestle in the feeling of physical agility, excitement, speed, and pure bliss that is carried within it. Today, living in the era of the digital age, there is a slight dread of the many games we played in our childhood leaving our minds – abandoned and disregarded, with none of it being passed down to the children of today. To prevent such an affair in the smallest capacity, we are going down a lane that will rekindle the deepest parts of our childhood. Especially intriguing are the traditional games that have etched themselves into our lives – carrying with them a rich heritage and a sense of cultural identity. One of such traditional game is Seven stones or what we call in our local language “Pithu” is rooted deeply in Indian culture and is a testament to the country’s rich heritage of simple yet engaging recreational activities. This outdoor game is not only a source of entertainment but also an excellent way to develop physical skills such as agility, precision, and teamwork among many children. It fosters a sense of community, encouraging them to play together and engage in healthy competition.

Pithu and its History

Pithu, also known as Seven Stones, is a traditional Indian game that involves knocking over a pile of seven stones with a ball and then attempting to rebuild the stack while avoiding being hit by the opposing team’s throws. This game is not only a test of agility and strategy but also promotes teamwork and coordination. It is a folk game popular in both rural areas and urban street corners. Known by various names across different regions, Pithu is called “Pithu” in Karnataka, “Satoliya” in Gujarat, “Lingorcha” in Maharashtra, and “Dabba Kali” in Kerala, Sitoliya in Rajasthan, lingorchya in Maharashtra and Ezhu kallu in Tamil-Nadu. Despite the game that is almost being forgotten and becoming extinct in past few decades, the inaugural world cup held in 2015 was a huge success paired with Indian Pithu premier league. The Indian premier league that was held in November 2017 had gathered great. momentum across nation which was organized by amateur Pithu federation. In year 2020 formation of the pithu federation of India have taken place and the first national tournament with 14 states and 24 teams was held in Indore followed by one in Bhopal in 2020.

This traditional game is a beloved pastime that transcends linguistic and cultural barriers, uniting players in the joy of outdoor play. To play this game, participants need physical movements, body flexibility, team coordination, reflex action, and spatial action. Therefore, it is also beneficial for the improvement in physical and psychological aspects. It also helps in children’s concentration, memory, as well as in physical health. Its revival in modern times is a testament to its timeless appeal and its ability to bring people together through simple yet engaging gameplay. But have you wondered that this outdoor game also has its own history?

Source: Twitter, 5000 years ago, children in cities of Indus Valley Civilisation played a game called Pithu. Made by broken terra cotta utensils and a ball made of old cloth stripes.

Finding evidences and artifacts from major historical and archaeological sites gives us detailed information about that region and Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization is no exception. According to Upinder Singh, in her book “A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India”,

it was mentioned that “A stacked set of terracotta discs, found in gradual sizes, was found at an open area behind the structural complex of Rakhigarhi.” This suggested the possibility that a game similar to pithu which goes back to early Harappan times!

Coming to ancient puranic times, Pithu’s history dates back to the Bhagavata Purana, a Hindu religious text that is claimed to be written 5000 years ago. This religious text mentions Lord Krishna playing the game with his friends. From the stories of Mahabharata, it has evolved through generations and is popularly known as Pithu, Saat-Pathar (seven stones), Pittu and several other names and though it deceives most at first site it is one of the most complex and popular children’s game in India. It is believed to have been originated in the southern parts of the Indian subcontinent. In ancient times, the game of Pittu was played by collecting stones, in which there was no limit on the number of players and time and there was no size of the playing field and players could stand anywhere as per their wish. It was also said that even in the ancient times, this game was also played for physical fitness, especially by king and warriors from the era of Indus valley period to medieval period.

The Game

Pithu is played between two teams: breakers and defenders. Seven flat discs of varying sizes are stacked in the decreasing order of size, and the goal of the breakers is to knock over the stack with a throw of the ball, usually a tennis ball or a rubber ball. They must then collectively restore it quickly before the defenders can collect the ball and tag any team member. The objective of the defending team is to strike any breaker with a throw of the ball, targeting below the knee level. If the ball touches any of the breakers, then that player and the entire team is declared out. The ball then goes to the opposing team, and the next game begins with the defenders now as breakers.

Source: Compassion blog, the breakers prepare to knock down the pile of stones with the ball, while the defenders get ready to prevent them from rebuilding the pile by hitting them with the ball.

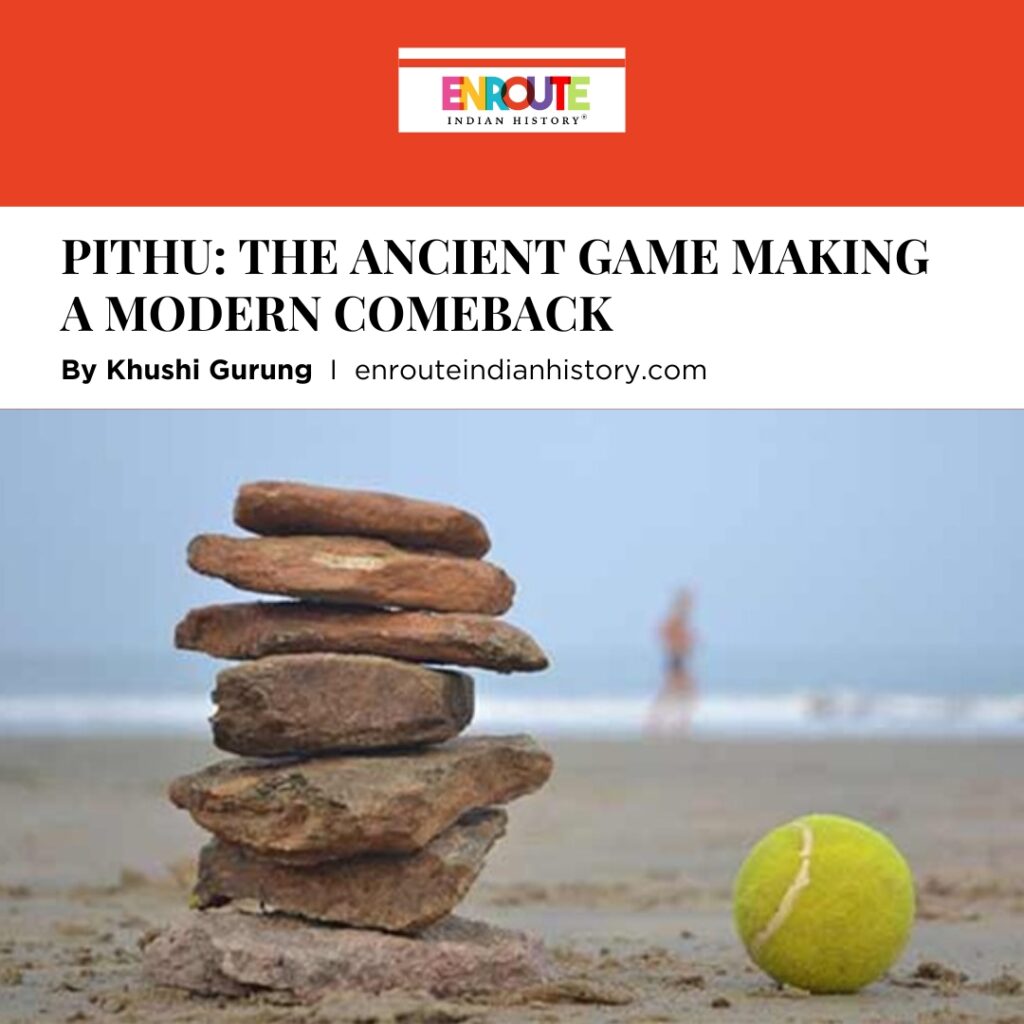

Firstly, the teams have to set boundaries for the playing field and then a circle is drawn in the centre of the field in which the seven stones are stacked on top of one another, with the smallest on the top to make a Pithu (stack). The striker team is called breakers, and the fielding team is known as defenders. A coin is tossed to choose which team will play the breakers’ role first. After the selection, the stones are stacked to form the Pithu. Any of the defenders can do this. The discs are stacked to provide maximum stability and resistance to soft hits by a ball. One of the defenders takes a position behind the stone stack at a distance of about 4 ft. to catch the ball thrown by the striker. To catch the ball from any direction, other players will take positions by scattering around the Pithu. All the breakers will take their position behind the crease line in the breakers’ part of the field. One of the breakers, generally the one considered the best at aiming, starts the game by attempting to strike the Pithu with a ball-throw from the crease line. If the Pithu is not disrupted and any defender catches the ball after the first bounce, then the striker will be declared out, and the next player of the breakers comes on the strike. If the Pithu is not disrupted and the defenders do not catch the ball, then the striker will get two more chances to knock over the stack. After three failed trials, that striker’s turn is over, and the next player from the breakers will play.

Source: Bhartiya Khel, Pictorial depiction of the playground of Pithu.

The breakers get nine chances in total—three chances each from three players—to break the Pithu. After the Pithu is broken, the defending players catch the ball and aim at the breakers to hit them below their knees or on their back. At the same time, the breakers gather near the Pithu and try to quickly restack the discs. They must stay alert to scatter rapidly because the defenders keep throwing the ball at them. The striker and rebuilders coordinate while dodging the ball thrown at them. This task is not easy because a member of the defending team stands near the Pithu,

waiting to get the ball from a teammate. After restacking the Pithu, the breakers trace a circle around it three times with their fingers and then shout ‘Pithu’. Thus, they get one point and also the chance to hit the stack again. However, if the defenders succeed in hitting any breaker before they rebuild and should Pithu, then the breaker team is out. The ball will then go to the defenders, and in the next game, they will be the breakers. When the defenders get the ball to hit the breakers, they must not run with the ball. Instead, the player with the ball must throw it either directly at the breakers or to a teammate who has better chances of aiming at the breakers. When the ball changes hands, the defenders play as the breakers.

Additional rules:

- If a striker cannot knock down the stack, then he or she is given two more chances—a total of three strikes. After three failed strikes, the ball goes to another team member.

- If the breakers cannot knock down the Pithu in nine tries, then the defenders get one point and will now get a turn to be the breakers.

- In any of the three tries, if the striker’s ball does not disrupt the stack and is caught by an opponent after one bounce (a tip) behind the Pithu, then the striker is out.

- Players from the defending team cannot run with a ball in their hand. The ball should not remain in the player’s hands for more than 3 seconds. They have to keep passing the ball to their teammates who can tag breakers conveniently.

- The throwing seeker cannot come too close to the piled-up stones while attempting to knock them over. They have to do so from behind a line marked on the ground.

- Each team contains an equal number of players.

- Piles of flat stones contain 7 stones.

- The seeker, after restoring the pile of stones, says the game’s name “Pithu!” to announce the reconstruction of the pile of stones.

- If the ball is thrown by the thrower and hits the piles and the opposite member catches the ball without hitting the ground, then the whole team gets out.

Source: Compassion blog, the defenders piling up the stones.

With addition to rules and gameplay, there are strategies for the players in the game. The Stricker should try to knock over only one or two top discs of the Pithu with a superficial hit to make it easier to restack rapidly. If the discs spread to far places with a powerful direct hit, then it would take longer to collect and rebuild the Pithu. The risk of a slow hit is that the ball stays close to the stack, increasing the chances of

the opposing team hitting the breakers. On the other hand, the strategy of the breakers is different. He/she should first focus on the actions and body language of the striker. Team up to rapidly rebuild the Pithu. At the same time, keep observing the moves of the defenders to avoid getting tagged out with the ball thrown by them. And lastly the fielders or the defenders have to be vigilant about all the moves on the playfield and keep passing the ball to the teammates nearest to the re-stackers. They should keep the ball moving to divert the attention of the breakers to impede the rebuilding of the pithu.

Source: Solution of history and software, A group of children playing lagori.

Modern Era

In the modern era, Pithu serves as a nostalgic bridge between generations, reconnecting adults with their childhood while introducing the younger generation to a game that is deeply rooted in Indian heritage. This resurgence can be attributed to growing awareness of the importance of physical activity in an era dominated by digital entertainment. Moreover, in an era dominated by digital entertainment and sedentary lifestyles, Pithu offers a refreshing and active alternative, promoting physical fitness, agility, and coordination among children and adults alike. As urbanization limits the spaces available for

traditional outdoor activities, the simplicity of Pithu, requiring minimal equipment and space, makes it an accessible and appealing choice for community gatherings and school events. It also continues to hold cultural and recreational significance in modern-day South Asia, serving as a bridge between generations and a reminder of simpler times.

As time passed by, most of these traditional games began to fade away and very few remained. Kabaddi, for example, became a global phenomenon after being pushed with the Pro Kabaddi League. A game that no kid talked about 7 years ago, is now being enthusiastically watched and played by almost every child of this generation. Fortunately, Kabaddi is not the only traditional sport who gained international popularity. Pithu, which was played a lot by the youth back in the day, has also begun to make its way to the international circuit. Today, Pithu is played by at least 30 nations across the world. The game has gradually gained a considerable amount of global prominence. However, India is the epicentre of the development of this game with a bigger platform and a wide outreach to contemporary audience.

Source: Pittu.org, The official logo of Pittu Federation of India.

Many national federations have also been initiated to revive this traditional game for instance the Pittu Federation of India (PFI), which is a registered by Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India. The PFI is affiliated to the South Asian Pittu Federation; Asian Pittu Federation and World Pittu Federation. Its main function is to govern and control the Pittu Sports in India. The Prime Minister of the country, Hon’ble Shri Narendra Modi, in his Mann Ki Baat talked about saving India’s most popular ancient and traditional game Pittu from extinction and making it popular again. According to the intention of the Prime Minister, the Pittu Federation of India was formed under the leadership of Shri Kailash Vijayvargiya. The main objective of the Federation is to re-popularize Pittu game by organizing competitions of Pittu sports from village level to national level with the same rules and to give equal opportunities and respect to the players and coaches of Pittu sports. The Indian Pithu Premier League that was held in November 2017 had gathered great momentum across the nation which was organised by the Amateur Pithu Federation of India. Moreover, Pithu is gaining recognition in educational settings as a means to promote holistic development. Schools and organizations are incorporating the game into their programs to enhance students’ motor skills, coordination, and teamwork. The game’s strategic element also fosters critical thinking and problem-solving abilities, making it a valuable tool for cognitive development.

In conclusion, Pithu is more than just a traditional Indian game; it is a testament to the timeless values of teamwork, strategy, and physical agility. Its simple yet engaging gameplay, requiring only a few stones and a ball, makes it accessible and enjoyable for people of all ages. Historically, Pithu has played a significant role in physical and social development, fostering coordination, endurance, and community spirit. In the modern era, its resurgence in schools and communities underscores its enduring relevance, promoting physical fitness, cognitive skills, and cultural heritage. Pithu stands as a bridge between past and present, offering a playful yet meaningful connection to India’s rich cultural legacy.

Bibliography

Vasanthan Sobhika, “Revisit the history and origins of traditional Indian games”, Homegrown, publish on: 3rd August, 2023 Available at: https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-explore/revisit-the-history-origins-of-traditional-indian-games

Vijay D, Gupta Abhishek, “Sprint Time Performance in Pittu: A Traditional Indian Sport”, Journal of Integrated Health Sciences, Department of Physiotherapy, Rajeev Gandhi College, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Mardi Sunita, Khandekar Prachi, Awachat Harshada, Sathe Abhinav, “Sprint Time Performance in Pittu: A Traditional Indian Sport”, ResearchGate, Oct 2023.

Enos Jayaseelan, “Seven Stones: A Traditional Game in India”, CompassionBlog, August 2012, Available at: https://blog.compassion.com/seven-stones-a-traditional-game-for-children-in-india/

Bharatiya Khel, “Lagori”, Available at: https://bharatiyakhel.in/lagori-pitthu/y

TopendSports, “Lagori / Pittu Garam / Seven Stones”, Available at: https://www.topendsports.com/sport/list/lagori.htm

Gade, P.V, “Traditional Indian Games: Origins and Evolution.” New Delhi: Cultural Heritage Publishers. 2018.

Sharma, A. (2017). “Games of the Indian Subcontinent. Journal of South Asian Studies”, 34(2), 145-167.