Diwali, the festival of lights, holds a paramount place in the tapestry of Indian cultural heritage, exuding a vibrant spectacle of significance, radiance, and profound symbolism. This jubilant celebration symbolizes the victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, and the triumph of good over evil. Embedded in the vast annals of Hindu mythology, it commemorates various legends, the most revered being the return of Lord Rama, along with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana, from their arduous exile and the defeat of the demon king Ravana. Adorned with a kaleidoscope of rituals, Diwali is a time when homes are adorned with vibrant rangoli designs, earthen lamps known as diyas illuminate every corner, and the air resonates with the crackle of fireworks. Families unite, exchanging gifts and sweets, embracing the spirit of togetherness and renewal. This festival transcends religious boundaries, uniting people in the warmth of its luminance, underscoring the essence of joy, hope, and the eternal radiance of light in our lives

Delhi chronicler and historian RV Smith suggests that the tales of Diwali’s celebration by the Pharaohs, illuminating the pyramids and the entire Nile region, followed by its observance by the Persians, served as an inspiration that deeply captivated the Mughals, leading them to develop a strong affection for the festival of lights. This fascination led to the creation of the Jashan-e-Chiraghan.

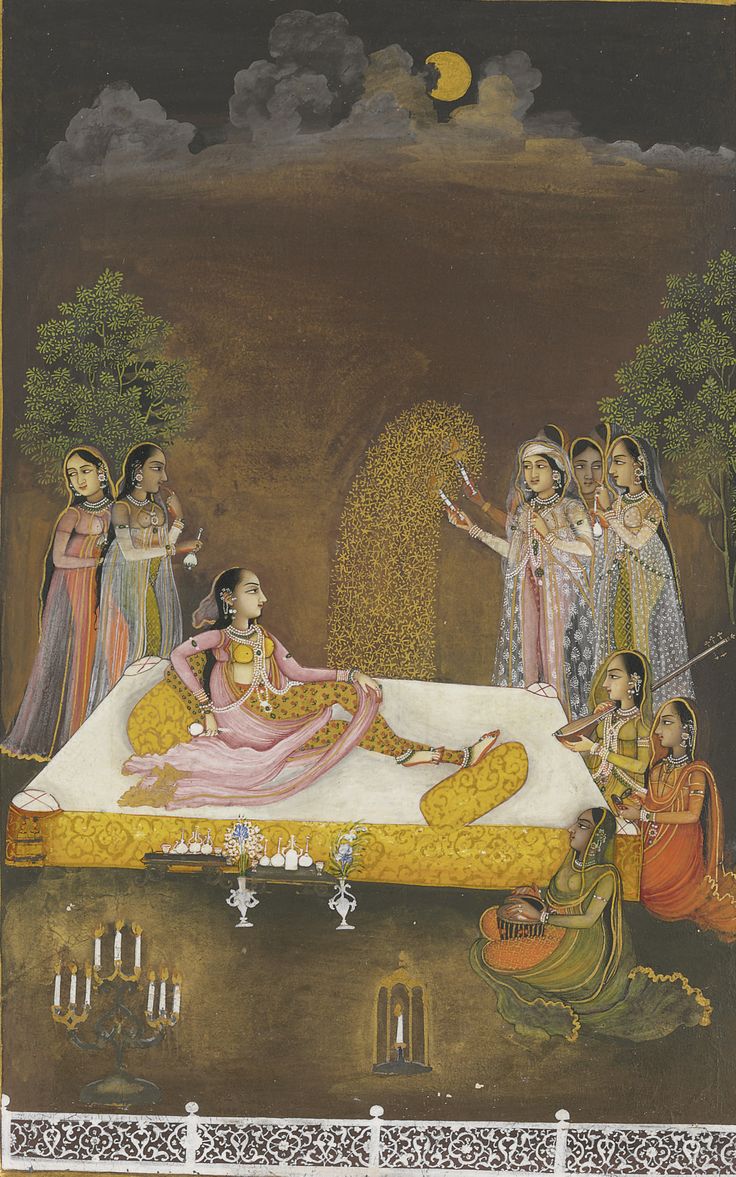

Royal women celebrating Diwali Lucknow, India ca. 1760

Source : Cleveland art

The Mughal association with Diwali began during Akbar’s reign at the Agra Fort and Fatehpur Sikri. Despite facing opposition from orthodox religious scholars (ulema) who deemed it an “un-Islamic practice” associated with devil worship, where owls, considered birds of omen, were sacrificed to the goddess of wealth, Akbar recognized the potential of Diwali not only to boost his popularity but also to foster coexistence between the two major religions in India. Abul Fazl, a courtier of Akbar, noted in the Ain-e-Akbari that Akbar aimed to comprehend various religions to govern more effectively, and festivals like Diwali provided a joyful way to achieve this understanding.

Shah Jahan elevated the grandeur of Diwali significantly. During the peak of Mughal power, he infused elements of Navroz traditions into Diwali to enhance its vibrancy. According to Smith, Shah Jahan maintained the fervor of Diwali celebrations even after relocating the capital to Delhi. Furthermore, he introduced a new aspect to the festivities within the fort by introducing the ‘Akash Diya’ (sky lamp).

A princess and ladies celebrating Diwali in a palace courtyard, in the presence of yogis and yogis. Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum

The festivities extended to the general populace as well. The palace distributed cauldrons of sherbets adorned with almonds and pistachios in earthen pots. Distinguishing it from the Dussehra tradition, the Diwali sherbet was white, potentially evolving into what we now know as thandai. The true celebration commenced in the evening when the royal gates welcomed guests. The palace is illuminated with a display of diyas, chiraghdaans (lampstands), jhaads (hanging chandeliers), and faanooses (pedestal chandeliers, sourced from Muradabad).

Aurangzeb, despite not being particularly fond of the grandeur and magnificence associated with Diwali, did accept gifts from his Hindu ministers. However, he prohibited music and any form of celebratory activities, effectively putting an end to the opulence of the Mughal Diwali and the general festivities in the court. It was only in the era of his great-grandson, Muhammad Shah, decades later, that the music and splendor returned to the Mughal court.

Jharokha portrait of Muhammad Shah holding an emerald and the mouthpiece of a huqqa ca. 1730 by Nidha Mal via The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, 1990.376

Muhammad Shah, originally known by his childhood name Roshan Akhtar, upon ascending the throne on September 29, 1719, was bestowed with the name Abu al-Fatih Nasiruddin Roshan Akhtar Muhammad Shah. However, he retained his surname Sada Rangeela. Consequently, over time, people began to refer to him as Muhammad Shah Rangeela.

Quli Khan, a courtier of Muhammad Shah Rangeela, depicted the era in his book “Markaye Delhi,” portraying a time when the people of Delhi were leading a particularly leisurely life. Historian William Dalrymple notes that although Muhammad Shah Rangeela was not regarded as one of the most successful Mughal emperors, his reign encouraged the promotion of the arts, leading to numerous extraordinary works in this domain.

Historian AV Smith records that Delhi’s Red Fort has been a site witnessing the celebrations of Diwali and Basant Utsav. During the period between 1720 and 1748, the Diwali festival was particularly celebrated in a unique and special manner during the reign of Muhammad Shah. Expansive grounds constructed in front of the palace were specifically arranged for these celebrations.

Muhammad Shah Rangeela celebrated Diwali with his queens and consorts, all adorned in new royal attire each year. Chandni Chowk became synonymous with ‘Rangeela Ki Diwali’ (Rangeela’s Diwali) due to his annual visits. He would arrive at Chandni Chowk accompanied by royal ladies and members of his harem to shop for various goods. Additionally, hundreds of people dressed in their festive attire would gather there to purchase new clothes, sweets, diyas, jewelry, and other items.

During the Diwali celebrations, Mohammad Shah Rangila would sit among his courtiers. Dancing girls would dance around fountains holding earthenware lamps, with some fountains spraying colored water, and rumors suggest that one even spouted liquor, which some nobleman reportedly drank to amuse the flamboyant emperor.

The Rang Mahal in the Red Fort was illuminated with diyas during Diwali, as depicted in a painting showing Emperor Mohammad Shah Rangeela celebrating Diwali outside the palace with some women.

According to Professor Najaf Haider, paintings from the Mughal era indicate an enduring interest in the use of firecrackers during that period. The principal feature of Mughal Diwali celebrations was the lighting of fireworks, often set off near the walls of the Red Fort under the supervision of the “Mir Atish” (the firework supervisor). Historian R. Nath notes that in a time without matches, the primary fire source was the “Surajkrant.” At noon, royal attendants exposed a round, shining stone known as the Suranjkrant to the sun’s rays. This heated stone would then ignite a piece of cotton. This celestial fire was preserved in a vessel called the “Agingir” (fire pot) and entrusted to the care of an official. It was utilized within the palace and renewed annually.

During the Mughal era, the emperor would be weighed in gold and silver, and these precious metals would then be distributed among the poor. It’s believed that some Mughal women would ascend to the top of the Qutub Minar to witness the lights and fireworks. Fireworks, supervised by the Mir Atish, were set off near the walls of the Red Fort. Shah’s Diwali celebrations at the Red Fort were funded through duwazdihi (donations) and marked one of the final occasions when the Akash Diya (the Light of the Sky) was ignited atop a 40-yard high pole supported by sixteen ropes. This grand spectacle was fueled by several maunds of binaula (cottonseed oil) to illuminate the darbar (royal court or audience).

As per Smith, the Akash Diya was installed within the fort and lit up during Diwali. Its radiance not only illuminated the fort but also cast light all the way up to Chandni Chowk. Around four maunds, equivalent to over 100 kilograms, of cotton-seed oil or mustard oil were used to fuel the lamp, requiring large ladders to replenish the vessel with oil and cotton. Nobles and affluent traders also illuminated their mansions with earthen lamps during these festivities.

Legend has it that the flamboyant emperor purchased all the oil in the city to illuminate the night, but while this might be an exaggeration, there were sufficient Telis (oil sellers) present to meet the needs of the general population. Some of these Telis were more than mere oil vendors; the saying in both Lahore and Delhi was ‘Parhhein Farsi aur bechein tel’ (Study Persian and sell oil). This phrase indicates that some of these individuals were intellectuals who, due to challenging circumstances, had to resort to such humble occupations.

The Sayyids of Barah, who were instrumental in Muhammad Shah’s ascension to the throne, along with other figures, including Muhammad Shah himself, hailed from twelve villages in what is presently Uttar Pradesh. In these villages, both Hindu and Muslim peasants celebrated Diwali with great enthusiasm. This shared tradition meant that these influential individuals were not surprised by the emperor’s extravagant and unusual spectacle during the Diwali celebrations.

During Dussehra, the emperor oversaw the ceremonial flying of the stunning Neelkanth bird and a procession of adorned horses and elephants. However, Diwali was a far more elaborate affair, requiring months of preparation. Orders for diyas (earthen lamps) and decorations were placed in advance. Cooks from various regions within and around the kingdom were invited to prepare exquisite dishes. Ingredients were imported from Persia and then soaked in a mixture of milk, honey, rose, and saffron to create delectable sweets. The Chappan Thal, ornate plates featuring sweets from 56 different kingdoms, formed an integral part of the Diwali celebrations.

Folklore abounds with tales of how kings and courtiers vied to outdo each other with gifts for the emperor. Lavish offerings such as costly jewelry, sweets, wines, and artifacts obtained from distant lands were paraded from their residences to the Diwan-e-Aam, the public audience hall, showcasing their generosity and allegiance to the king.

Rangila’s Diwali, as described by Mughal historians such as Munshi Fayazuddin, established the essence of contemporary Diwali celebrations. The emperor perpetuated this magnificence by commissioning artists like Mal to capture the celebrations on canvas. A renowned artwork depicting Rangila observing the fireworks from an adorned parapet of the Red Fort is still regarded as one of the most exquisite representations of the royal festivities during that period.

REFERENCES:

- Smith, R. V. (2015). Delhi: Unknown Tales of a City (1st ed.). Lotus.

- Statesman News Service & Statesman News Service. (2018, November 4). The lure of Diwali in Delhi – Past and Present. The Statesman. https://www.thestatesman.com/features/the-lure-of-diwali-in-delhi-past-and-present-1502704787.html

- Khanna, A. (2021, November 12). A ROYAL DIWALI – The Daily Guardian. The Daily Guardian. https://thedailyguardian.com/a-royal-diwali/

- Smith, R. (2019, October 28). Diwali or Jashan-e-Chiraghan during Mughal reign. https://www.outlookindia.com/.https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/opinion-diwali-or-jashan-e-chiraghan-during-mughal-reign/341245/amp

- April 4, 2024

- 7 Min Read