Article Written By EIH Researcher

Juhi Mathur

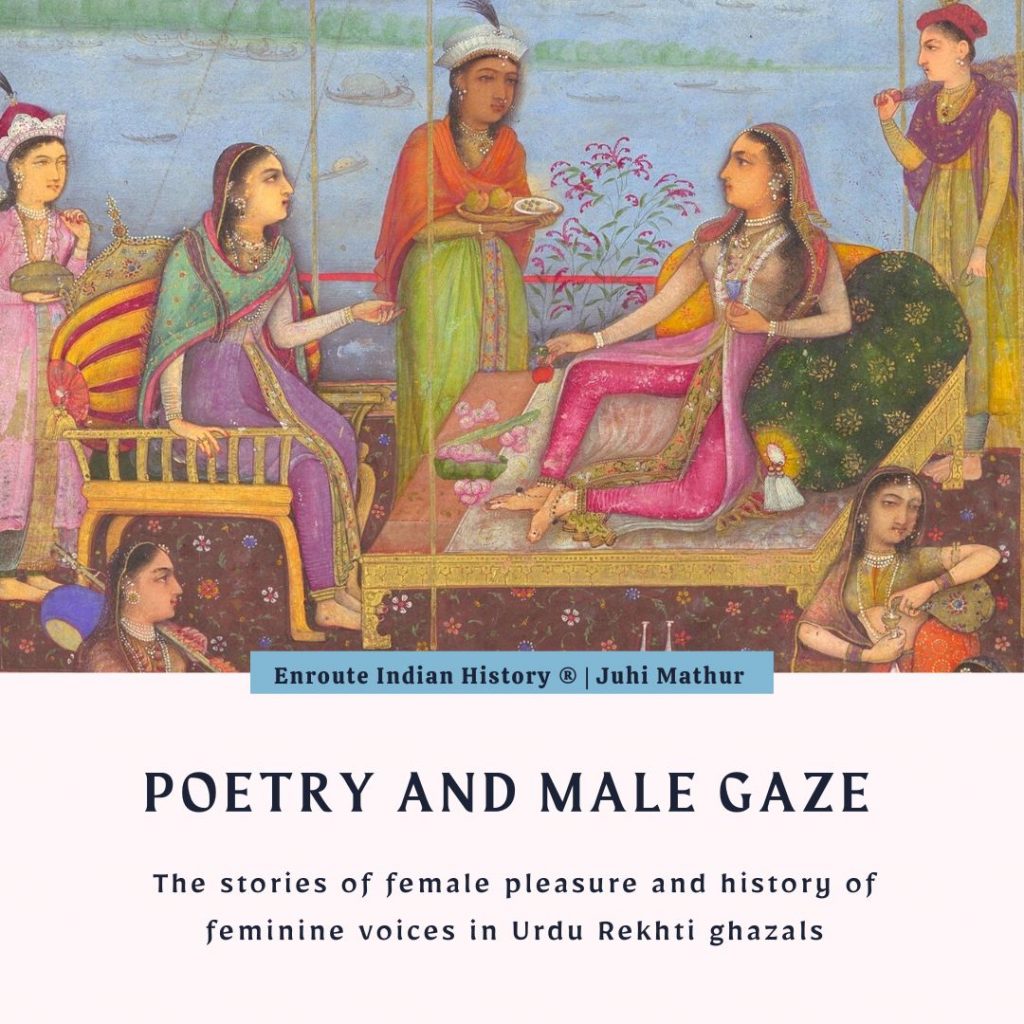

In many ways poetry and literature produced in any era is a reflection of its time, a product of its master governed by cultural and socio-political developments that are evolving simultaneously.A delve into the human psyche poetry is a point of exposure, the words become witness to the artistic interpretations of realities. In the vein of this poetic metaphor, Rekhti poetry takes us on a journey where we land into the imaginations of Awadhi poets. In a domestic space, where explorations of a woman’s desire and her space take forefront. In the lanes of Rekhti, every nook and corner carried the stories of desire, planted with houses of female relationships, adulterous couples fulfilling their amorous desires and the plight of a concubine became known as poetry entered private spaces of women and public alike. Rekhti thrived in the ‘decadent’ Nawabi courts of Lucknow, the refined, cultured and artistic expression of carnal desires became a reverent topic among the poets.

Rekhti, the feminine of Rekhta, is a term coined by poet Sa’adat Yar Khan “Rangin” (1755–1835) for the genre of Urdu poetry that emerged in southern India in the eighteenth century, and of which Rangin himself was a prominent exponent.

Rekhti poetry explores the themes of love, and facilitates a deeper study into the idea of female agency. Poetry and literature celebrated female pleasure, female agency and the concept of social relationships that women shared with their surroundings. Although these ideas slowly turned into taboo as our country underwent a wave of reformist movements as a response to the colonial regime. T. Graham Bailey calls Rekhti the language of ‘women of no reputation’ and the poetry of ‘a debased form of lyric invented by a debased mind in a debased age.’

The history and origin of Rekhti is as rich and diverse as its creators. Before rekhti became associated with Lucknow and Nawabi culture, it was already thriving in the Deccani court of Muhammad Quli Qubt Shah. In Deccan, several poets were already creating ghazals and textual works that could be considered as precursors of Rekhti. The Mushairas in the regions of Bijapur and Hyderabad were one of the spaces where rekhti poetry was shared as a form of entertainment.

Syed Meeran Hashmi was a court poet of Sultan Ali Adil Shah II of Bijapur. He composed extensively in the Rékhtī genre. Modern thought would never accept the compositions of male Dakhnī poets in rekhtī as being true representations of medieval women. Hashmi is considered by many to be the master of this genre and a bulk of his compositions testify to his mastery of the form.” Before Hashmi, Deccani poets used two modes for Urdu ghazals- namely Persian and Indic. In Persian compositions poets used the male voice to address their beloved, usually a female, whereas according to Indic mode, the poet used a feminine voice usually directed towards a male lover, the object of desire. Deccani poets oftentimes used both the modes, sometimes incorporating them in the same ghazal. We often associate the Rekhti genre simply with the female voice used in poetry; the primary bifurcation arises with the vocabulary as well the themes of Rekhti poems that differ from standard Urdu ghazals. This was illustrated in the works of Hashmi, where he incorporated the domestic spaces occupied by the elite women of his society, and he added the more feminine vocabulary and experiences as compared to the spiritual and carnal love that ghazals boasted about. Although the nomenclature did not exist around the time Hashmi wrote these works, his ghazals did have the earliest elements of Rekhti. Thus it is suffice to say that the tradition of rekhti poetry traveled to northern parts of India through the rich poetic culture of Deccan.

Rekhti Ghazals

It is a known fact in the literary world that the themes of female pleasure and companionship have been visually represented since premodern times and they hold a lot of value as part of literary histories exploring the social and cultural lives of women. Rekhti poetry is a product of two rich cultures intermingling- namely the ancient indian texts delineating traditions of sexual practices, customs, foreplay , the most prominent being Kamasutra and the Perso-Arabic eroticas like Arabian nights that consists of female characters who have amorous desires and passions, stuck in loveless marriages or attracted to other men or women. The feminine urges, needs and relationships that developed in the domestic spaces of elite women became turned into a form of entertainment. This development led to the incorporation of elements of humour in Rekhti poetry.

Unlike the standard Urdu ghazal where most of the characters are male and the beloved’s gender is usually ambitious, Ruth Vanita explains that in the ‘Rekhti ghazal, the cast includes the speaker-persona, gendered female, who has many preoccupations, including love, friendship, family, apparel, rituals, and festivals; her female friends and sometimes her female lover, ranked in order of importance by identifying terms; her servants; her relatives, such as co-wives and sisters-in-law; her female neighbors; her husband; her male friends and lovers, of whom the poet is occasionally represented as one; her female rivals; very occasionally her children; and the poet, whose pen-name, which may be male or female, appears in the last or signature line.’

Male Poets and female sensuality

In Rekhti ghazals the relative statuses and the degree of intimacy between the women are indicated by the terms the persona-speaker uses to address her. She may be addressed as Anna or Dai, which indicates that she is a wet nurse. Like the servant addressed as Dadda, she is a mature woman who has raised the persona from childhood and accompanied her to her marital home. Women friends and neighbors are addressed as Begam (lady), or as Bahan (sister) and Baji or Apa (older sister). The terms Dogana or Zanakhi are usually used to denote female companions and have erotic connotations. In Urdu, chapti, chapatbazi, denote female homosexual activities and other terms that are used to define intimate female companions are illaichi(cardamom), dost(friend), sahgana(of three types), and guiyan(friend of a woman, partnerin terms of male relationship). They have been mentioned in Rangin’s manuscript where he has defined how these different relationships have been defined and developed.

Illaichi is used as a term for women who share food together,specifically feeding grains of cardamom to each other in private which leads to growing intimacy. Dogana is used to denote women who share twin parts of an almond. Zanakhi is used to denote the term where the lovers break the chicken wishbone and become Zanakhi. The person who gets the bigger part of the bone after breaking it is designated male and it both the parties get equal halves, they get another roasted chicken and continue to break the wishbone until one of them receives the bigger half.

In the verses compiled in the manuscript Rekhti of Divan-e Angekhta, Rangin also provides a more detailed account of the rituals used to set up the relationships of Dogana, Zanakhi, and Ilaichi. It is an illuminating study of intimacy and how it develops via food. In Indian customs food becomes an important marker in forging relationships. The act of eating becomes prominent in establishing any type of intimate relationship between two women. The act of eating together, sharing food in itself carries connotations of familial relationships, as we see in various Indian customs like weddings where couples share food from the same plate as a part of ritual.

Through their , Saleem Kidwai and Ruth Vanita are able to look at the various facets of female companionships where sisterhood is as important as the erotic relationships shared by women. And how the non elite language, varied regional as well as religious idioms were also common in the ghazals.

Yun hi main gash hui Dogana par Raja Nal jaise tha Daman par gash. I swooned [with love] over my Dogana, As King Nala swooned over Damyanti [Hindu mythological lovers].—”Insha”

In this verse Ruth Vanita points out that Insha’s comparison here of the woman speaker and her woman lover to famous heterosexual lovers Nala and Damyanti indicates that Rekhti celebrates female-female love, not just female-female sex, as some critics have argued. The comparison to lovers from Hindu rather than Islamic myth is significant. That the female speaker compares herself to a male lover entranced by a female beloved indicates gendered role-play.

These verses delve into different facets of a romantic relationship, where the woman speaks about her lover’s beauty, the clothes her lover wears, the act of undressing, lovemaking, the sadness and anguish she faces when her lover leaves her. The separate households both women live in hence the longing, the nightly rendezvous when the lovers meet during nighttime, the thrill of these experiences make rekhti poetry a sublime picture of love, companionship, and friendship.

Rekhti poems represent multiple characters with different points of view on many subjects, including that of female-female love. Sometimes it is celebrated and sometimes it is criticised. But it is present and acknowledged, whether it is the pleasure that resides in union or the poet writes about the pangs of seperation and woes in love.

O God, may no one be inclined to desire, And if they are, may they be inclined to commitment. I am given to Dogana As the moss is given to greenness. The path of love is very rough. Why should anyone take to such a wretched path?- Rangin

Exploring the female sexuality and intimacy two poems by Jur‘at and two by Rangin, (all entitled “Chaptinamas” [Accounts of Chapti] are extended narratives that focus exclusively on female-female liaisons, but also contain much more explicit accounts of female-female sex. It becomes clearer through these words that there was not a lot ambiguity where the gender of the beloved was concerned. Poems had the mention of breasts, the blouse and the skirt, the jewellery worn by the beloved that made Rekhti a discourse on the earthly delights rather than the desire for union with divine ( a common motif in standard ghazals).

Despite associating Rekhti primarily with sexual experiences of women of its times, the themes of Rekhti evolved with time. Mir Yar Ali ‘Jan Sahib’ (1810-1886) grew up in Lucknow, after the dissolution of Avadh in 1856 he briefly lived in Bhopal and Delhi before settling in Rampur. Under the patronage of the navab of Rampur, Jan sahib wrote solely Rekhti ghazals, but the themes he dabbled with were social and political commentaries and held a more empathetic view of women. The sexual escapades ceased to be discussed with similar vigour as in the past and the household spaces were taking forefront. Jan Sahib’s contemporaries went in similar direction where the extended household and the relationship of a woman with her family members dominated the thematic ethos in Rekhti ghazals.

While Hashmi wrote his ghazals in Persian and Indic forms and even added Rekhtis in his ghazals, the later poets like Qais, Insha and Rangin wrote the standard ghazals in Persian and separately wrote the Rekhtis. They were mainly for entertainment and weren’t didactic in nature. Jan Sahib solely composed verses for Rekhti ghazals and even though his verses also catered to the male audience, and did often times mock the sensitivity and emotional experiences of women, it did have more empathy as compared to the motives of his predecessors.

‘Tis pairu mein uthi hui miri jaan gayi

Mat sita miri dogana, mein tiri qurban gayi – Rangin

(This throb below has nearly killed me,

Dear one, don’t tease me so, you have already done me in.)

The term Dogana is specifically used in Rekhti poetry and connotes to the erotic relationships between the characters mentioned in the verse.

Performance and Poetry

The tradition of Rekhti poetry has still not entered mainstream discourse and the homoerotic themes have usually been censored even while publishing the works of famous poets who wrote Rekhti ghazals. The material acts of performing Rekhti poems in mushairas among the male audience has made many critics and reformers uncomfortable, this discomfort has been a significant result of colonialism and how the British saw various Indian cultural practices as decadent and hedonistic.

Rekhti poets often took female pen-names, such as “Begam,” “Pari,” and “Dogana.” Some, like Jan Saheb, also wore female apparel and mimicked female voices and gestures when they read their Rekhti in poets’ gatherings. Others, like Insha, enacted different roles as they read the different parts in the poems, thus bringing in the elements of impersonation as well as performativity.

Female and Rekhti poetry

The Rekhti ghazals, with the exception of few women, predominantly existed in the patriarchal structures, written by male poets, as a form of entertainment and catered to male gaze. It was performed in spaces that were dominated by male patrons and male performers impersonating women. It becomes a poignant commentary on voyeurism and male gaze that is focused on titillation. Even though the Rekhti poems facilitate intensive study into the mannerism and psyche of feminine desires and lifestyle, it was inaccessible for women.

According to CM Naim, there were not a lot of women who wrote Rekhti poetry, most notably the temporary wife (Mamtua) of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah or the maidservant of Sulaiman Shikoh, Naubahar who wrote under the pen name or takhallus ‘Zalil’ (shameless). In the present day, only a few known works of Zalil survive, indicating the intensive censoring that made its way when colonialism sensibilities strengthened their hold in the subcontinent.

Conclusion

To judge Rekhti only by comparison to standard Urdu poetry would mean disregarding its connections with native languages of non-elite populations, its status as a new form of urbanity born in the cultured Lucknavi society.Rekhti poetry became the urban expression of creativity and cultural synthesis that birthed these artistic endeavours. Rekhti does deal with the themes of same-sex love as well as paints a picture of the domestic lives of courtesans, elite women and ooncbubines in words that are unambiguously direct, sharp and transparent. The lovelorn frankness with which a woman expresses her desires is celebratory, revolutionary and even necessary in the face of otherwise moralistic erasure of female voices in literary histories. Having said that, it would be an anachronistic view to claim that Rekhti is solely feminist in its nature, when male gaze influences the interactions between women almost entirely. The mocking of peevish women for the entertainment of the male audience carries the undertones of the patriarchal vision of female sexuality. The fetishisation of lesbian relationships as well as of female desires in heterosexual relationships is rampant even today, the male gaze and romanticisation of the plight of a beloved and her lover are still dominant in visual and literary cultures. Thus, holding Rekhti as a symbol of female liberation and sexual freedom would mean overlooking the male gaze that facilitated it. Instead we can look at Rekhti as a way of expression. The mode through which we might understand the concept of feminine voice, the place of a woman in a society where their lives could become exaggerated story pieces for entertainment in spaces forbidden for the womenfolk. Rekhti did give feminine desires a voice and it even incorporated the female persona of Riti poetry in Urdu ghazals, hence expanding the representation of nayika in diverse cultural avenues, and it gave what little representation women could find in an otherwise intensively patriarchal atmosphere.

A medium through which we as members of modern society can question the nuances hidden in the meanings of ‘feminine voice’ , female centric stories and female pleasure, while simultaneously questioning the male driven narratives and the male gaze associated with it. But its subsequent erasure from the pages of history and designating the male poets writing rekhti as effeminate does make Rekhti ghazals and their revival revolutionary in nature. Is it really one of the earliest waves of feminism in our country or is it a mere extension of male fantasies? That i will leave it up to the readers.

Bibliography

“Married among their companions”: Female Homoerotic relations in nineteenth- century Urdu Rekhti poetry in India, by Ruth Vanita

Transvestic Words?: The Rekhti in Urdu by C.M Naim

Rekhti, Rekhti and how women found their voice in Urdu poetry, by Rana Safvi

Same-Sex love in India, A Literary History by Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai

Love and Eros in the Rekhti Texts, by Madhumita Mukherjee