Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Yoshwameki Ropmay

The Renaissance has been regarded as a glorious period where art and innovation reached its zenith of perfection and adoration. It was a time of rebirth and expansion for religious interpretation, scientific discovery, exploration of new lands and flourishing of the arts. The Renaissance took place in Italy but its innovation and ideas advanced far and wide. India under the Mughal rule was notable for its openness to the multiple ethnicities and religious toleration; a main reason why ideas of the renaissance can be seen to be an influence in their society and visual arts. This essay will focus upon how certain elements of the renaissance began to develop in the art of the Mughals. The first chapter discusses briefly the meeting between the Europeans and the Mughal kings and how they developed an interest in a new culture and its eventual integration. The second chapter focuses on the influence of renaissance in the art and how the Mughals used this to their advantage in promoting their cultural superiority.

European and Mughal elites

The tools that were developed in the Middle Ages for exploration continued to be used during the renaissance. One of them was an astrolabe – a portable device which was used by sailors to help in navigation. The functional working of the magnetic compass was also improved upon. Maps also became more reliable as cartographers began to incorporate information provided by travelers and explorers into their work. Shipbuilding was also improved upon and had begun to be empowered by sail rather than men with oars. Although navigation was still an inaccurate science, sailors were able to go farther than they had been able to before. This was an important aspect because as the economy during the renaissance began to prosper, there was an increasing demand for imported goods and new places to export local goods.

Among the Italians, Portuguese and Spaniards present in the subcontinent by the early sixteenth century were merchants sent by the Medici family to report on the prospect of regulating commercial relations. The Portuguese had already established their ‘Estado da India’ with their center of operations in Cochin and Goa by the time Babur captured Delhi in 1526. They had spread their control over Indian Ocean trade routes competing with the Mamluks, Ottomans and Venetians. We do not know how much interaction there was between Babur and Humayun with the Europeans, however we do know that the latter possessed articles made in Europe such as textiles, clothing and drawings. The Portuguese historian, Diogo do Couto recounts that Humayun acquired a Book of Hours, a traditional medieval manuscript of prayers from a Portuguese man. The man also showed the emperor illustrations of King David and Bathsheba to assess his knowledge of the Bible and was surprised that the Muslim ruler was well versed in the story and explained the iconography.

Akbar also formed connections with the Europeans that ranged from diplomatic and cultural to economic and military resulting in an increase in renaissance materials at Mughal libraries and workshops. In the 1570s, the Mughals established their dominance over large portions of India undermining the authority of European power on the subcontinent and beyond. Amidst the military tensions, Akbar began to express more clearly his interest in European intellectual and material culture. The Akbarnama also reports that during the Siege of Surat in 1573, there were a large number of Christians from Goa who came to Akbar and presented themselves as ambassadors. The envoys to Goa also had orders to bring back specific articles as well as expert artisans and musicians. The embassy to Goa in 1575 thus included artists, musicians and craftsmen who remained for a year or two to learn the styles and techniques of European art and architecture. Therefore, Akbar’s interest in the renaissance influence was self-serving and mixed with notions of intellectual curiosity and cultural superiority.

Renaissance influence and purpose on Mughal art

Jahangir Shoots the Head of Malik Ambar, by Abu’l Hasan, ca. 1616, folio from an album, Mughal India. Chester Beatty Library.

The Mughal elite and intellectual were broadly interested in European art and sciences. The impression given in their art is an insertion of European ideas and philosophy into their language of power meant to signify their universal rule. The Mughal Emperor was conceived to be an embodiment of a universal monarch around whom all political and social organizations should center itself with. This idea of Mughal suzerainty is beautifully depicted in a 17th century painting of Jahangir shooting the head of his enemy Malik Ambar (Fig. 1). The image can be interpreted as a mashup of Eastern and Western elements – the fish and bull are directly taken from ancient Arabic cosmology where they supported the theory of a flat word; the globe that they supported is a replica of imported European artifacts which were bought by the Mughal ruling class wherein Jahangir repeats the Spanish claim of ‘ruler of the round world.”; the gold chain with bells was a device of mythical Persian kings constituting the final court of appeal signifying that the whole world sought justice from the majesty of Jahangir; the emblems of military and royal victory are portrayed by child-angels in the contemporary European style while the gesture of shooting a bow harkens back to Turkic tradition.

Jahangir, and Jesus, by Hashim above and by Abu’l Hasan below, ca. 1618–20,

ca. 1610–15, Mughal India. Chester Beatty Library.

The visual language that the artists created served the broad cultural horizons of the Mughal aristocracy wherein their cosmopolitan tendencies were examined in relation to their politico-religious policies. The recent studies of Mughal paintings have emphasized the concepts of hybridity and fusion in the European tradition that the artists used in their compositions along with the Persian and Indian styles. While Christian iconography and renaissance technique was unique in Mughal culture, Persianate tradition was part of the Mughal world since its inception while Indic tradition was local and accessible. The Mughal successfully and purposefully appropriated European models into their tradition. Art under the Mughals reflected a diversity of visual traditions specially developed from their writings on policy, law, literature, religion and philosophy. The Mughals saw the incorporation of European art opportunities as a way to display their broad intellectual identities, cultural pluralism, state policies and openness to other traditions which became facets of their own cultural superiority – taking as an example the image of Emperor Jahangir who is hierarchically positioned above Jesus, holding the globe which was a symbol of power associated with Christ (Fig. 2). The artists were actively transforming foreign elements to represent their own ideas of kingship, policy and religious authority.

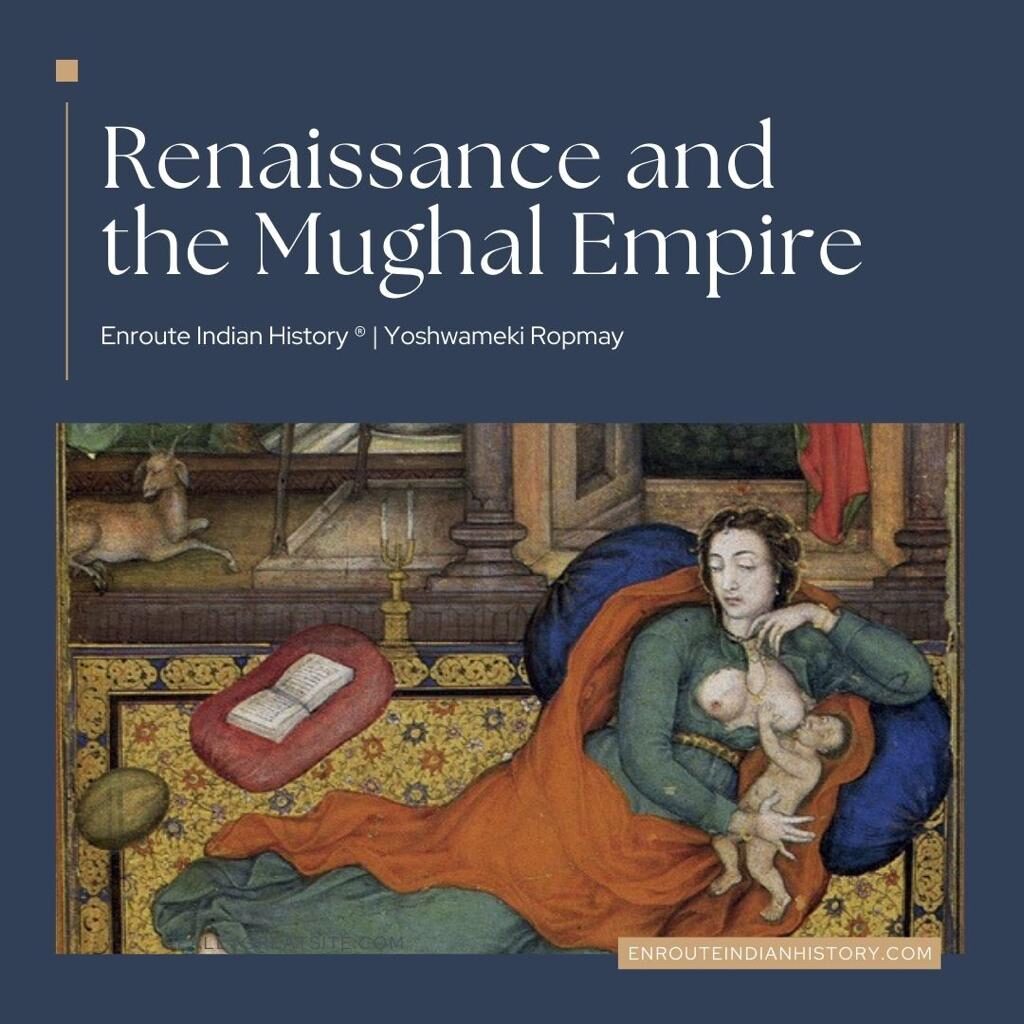

The Virgin and Child, by Basawan, ca. 1590, Mughal

India. Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, The San Diego Museum of Art.

The Mughal version of the Virgin and Child (Fig. 3) is another example of Mughal artists repurposing European elements and transforming them to embody Persian and Arabic literary motifs. The image presents a light-skinned woman nursing her infant on a lavish golden carpet laid down in a garden. The painting appears in a folio from a Mughal album and the Persian couplet above the picture identifies her as a moon born in beauty, a beautiful idol that gives milk. The Persian lines below the image translate her to a rose sprung from the waters of beauty. While the image bears residual similarity to the famous painting by Masaccio, upon closer examination, we realize that the female figure is not the nursing Madonna and the infant, not the Christ child. In renaissance tradition, Mary typically sits upright and cradles the baby in her arms while looking at it with loving motherly eyes. In the Mughal painting, the woman is seen lounging on a golden carpet with her head turned away from the baby who lies on the ground and does not seem to be emotionally engaging with him or her. The painting therefore exemplifies the creation of an indigenous visual language that resonated with the cultural pluralism of the Mughal nobility. While the inclusion of European elements was intentional, the painters rejected other features that did not fit with Mughal ideological and aesthetic ideas. This identification of repurposing, adaptation, appropriation and transformation therefore helps us to understand what the Mughal patrons and their artists thought of European art and how they wanted those elements to function.

REFERENCES

Alam, Muzaffar and Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. Writing the Mughal World: Studies on Culture and Politics. Columbia University Press, 2011.

Ash, Eric H. “Navigation Techniques and Practice in the Renaissance.” The History of Cartography, edited by David Woodward, Volume 3 (Part 1), The University of Chicago Press Home, 2007, pp. 509-527.

Minisalle, Gregory. Images of Thought: Visuality in Islamic India, 1550-1750. Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006.

Natif, Mika. Mughal Occidentalism: Artistic Encounters between Europe and Asia at the Courts of India, 1580 – 1630. Brill Academic Press, 2018.

Okada, Amina. Indian Miniatures of the Mughal Court. H.N. Abrams, 1992.

Silva, Nuno Vasallo e and Flores, Jorge. Goa and the Great Mughal. Scala Arts and Heritage, 2011.