Rethinking Human Evolution: The Unexpected Story of Homo naledi

- iamanoushkajain

- May 7, 2025

BY VAIBHAVI DHANWAR

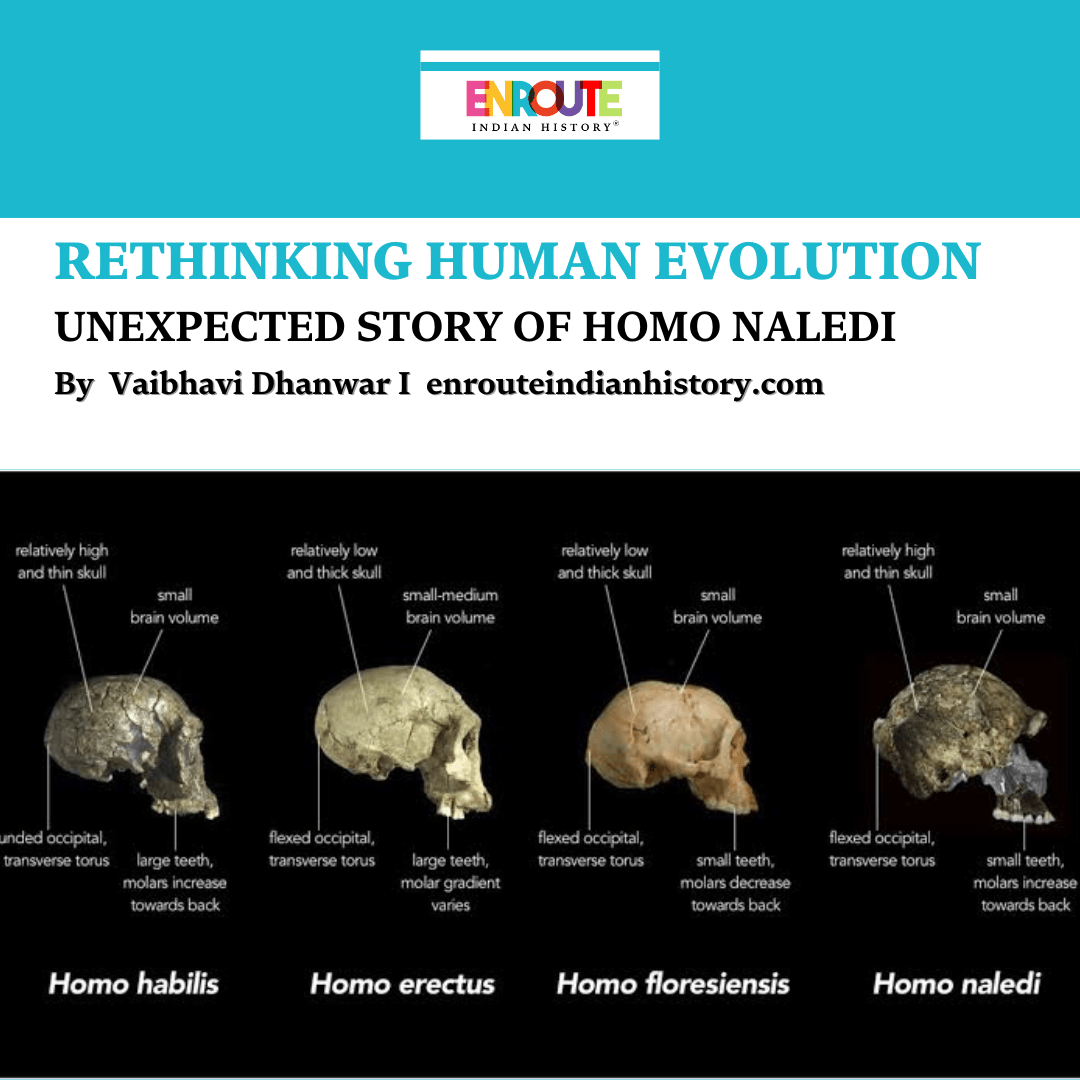

For millennia, human evolution has been represented as a linear march of progress, with every ancestor species giving way to a smarter and more able successor, reaching its culmination in Homo sapiens as the culmination of development. The discovery of Homo naledi, a diminutive brained hominin that coexisted with early modern humans. With a brain as big as much earlier ancestors but signs of behaviors long believed to be exclusive to Homo sapiens, Homo naledi makes us reevaluate old presumptions regarding intelligence, adaptation, and what exactly it means to be human. Does the size of the brain determine intelligence? Is human evolution a linear ladder of improvement, or an interconnected web of variable species existing together and impacting each other? By defying the strict categorizations that have so long dominated our comprehension of human history, Homo naledi unfolds a much more intricate and intriguing narrative of evolution in which survival, intelligence, and identity are not strictly controlled by size or by ranking but by accommodation and the complex interweaving of species.

Breaking the Linear Model of Human Progress

Human evolution has been perceived as a linear progression for most of history, a relentless march from primitive forebears to the smart, tool wielding species that we are today. The earlier hominins were successively displaced by more sophisticated species, leading up to Homo sapiens as the pinnacle of evolutionary achievement. The discovery of Homo naledi throws this narrative severely into question. The existence of a small brained [465 to 610 cm] species with apparently primitive anatomy only 335,000 to 236,000 years ago, alongside early Homo sapiens indicates human evolution was a convoluted pattern rather than a linear one, involving interlocking species with different characteristics and capabilities. The existence of Homo naledi in the fossil record compels us to rethink how we define progress in human evolution.

Historically, brain size has been correlated with greater intelligence and evolutionary progress. Although, with its diminutive brain, Homo naledi could have been practicing behaviors previously assumed to be the sole preserve of modern humans like intentional burial of the dead. If this is so, it refutes the hypothesis that intellectual sophistication is absolutely correlated with brain size. Instead of looking at human evolution as a ladder with distinct phases of progress, we have to recognize a mosaic evolution in which various species, with divergent levels of mental and physical adaptations, coexisted at the same point in time. This finding also emphasizes that human evolution was not merely a question of survival for the most advanced species but more a matter of adapting to various environments and situations. As Neanderthals survived Ice Age Europe when early Homo sapiens spread through Africa, so Homo naledi seems to have persisted in specialized ecological niches in the presence of larger grained hominins.

This realization reshapes how we think about intelligence, survival, and what it truly means to be human. Instead of assuming a single dominant species replaced all others, Homo naledi suggests that multiple human-like species coexisted, each with its own strengths, weaknesses, and adaptations. Hence might create a hierarchy over one another, the following explores that further.

Subverting Long Entrenched Human Superiority

Human beings have, for centuries, considered themselves the pinnacle of evolution, describing intelligence, civilization, and advancement in terms of their own achievements. This attitude has tended to reinforce the supposition that big brains, elaborate tool use, and sophisticated societal structures are the hallmarks of intelligence. Homo naledi puts paid to that. With a brain volume of just 465 to 610 cm about the same as Australopithecines and much less than that of present day humans Homo naledi was supposed to be an earlier evolutionary stage. More striking is the indication that Homo naledi performed behaviors previously reserved for bigger brained hominins, like purposeful disposal of the dead. If such a low brained species could manage to be cognitively advanced, then intelligence and humanity’s supremacy would no longer be so black and white as usually presupposed. The significance of Homo naledi extends beyond biological classification, it forces us to rethink the criteria for what it means to be advanced or human. For a long time, Western science has often equated brain size with intelligence, a perspective that has influenced everything from the way early hominin fossils were interpreted to how intelligence is ranked among modern human populations.

Yet the fact that Homo naledi coexisted with Homo sapiens implies that cognitive power and behavioral sophistication do not always correlate with brain size. This insight defies the long standing assumption that intelligence developed in a linear, hierarchical fashion, with modern humans at the apex and previous hominins as inferior beings. Rather, Homo naledi affirms the theory that intelligence evolved in varied and surprising manners, with several hominin species evolving special adaptations instead of merely advancing toward a single superior form. This finding also has larger implications for how we define human identity. If small brained hominins were able to engage in behaviors previously reserved for modern humans such as social cooperation, possible symbolic thinking, and perhaps even tool use then modern ideas on human superiority need to be challenged.

It raises age-old questions: Is intelligence solely a case of brain size, or is it a question of adaptability and problem-solving? Do practices such as ritualistic burial establish what it means to be human, even if they arise in forms that appear unlike us? By responding to these queries, Homo naledi refutes the outdated paradigm that modern humans represent the final stage of evolution, instead offering a richer and more comprehensive understanding of what it means to be human. The 2015 unveiling of the Naledi fossils challenged conventional views on human evolution. By calling them Almost Human, Berger and his team sought to emphasize their closeness to humans. Though, this inadvertently exposed the fragility of humanness as a fixed concept, one historically shaped by race and animality. Instead of reinforcing human ontological grounding, the discovery unsettled it, questioning rigid species classifications that separate humans from animals. [Benita de Robillard, 2018]

Science And Culture Interplay

Although anthropology and paleoanthropology attempt to be scientific, it is history and culture that typically inform the interpretation of findings. The example of Homo naledi is case in point. When initially found, it caught many researchers off guard due to its small brain size and relatively modern age, which challenged conventional beliefs regarding human evolution. The initial reservations among certain scientists were not so much regarding the fossil record itself but the fact that it presented an overlap of a low brained hominin with early Homo sapiens that conflicted with a linear increase in intelligence and complexity.

If a species with a brain much smaller than that of contemporary humans showed behaviors like potential ritualistic handling of the dead, then definitions of intelligence, culture, and human self must be redone. That rethink dissolves the anthropocentric assumption that mental acuity is based solely upon brain size, compelling scientists to use more multi-faceted criteria of intelligence, including behavioral and social complexity. Paleolithic archaeologist Jessica Thompson argues that evolution is not a simple, linear progression from monkeys to apes to humans, suddenly resulting in people. Instead, the process is far more complex [Sample, 2017].

The finding of Homo naledi forces us to reconsider not only the mechanisms of evolution, but what we mean by being human. We have for too long described our past as a straight-line march of progress, calibrating it to increase in brain size, tool use, and the characteristics we can see ourselves in. But Homo naledi, with its diminutive brain and potential for symbolic actions, shatters this fantasy of a single route to intelligence. Rather, it discloses a more complex, entwined history, one in which several species made their way through existence in different manners, defying our ideas about superiority and the strictures of what constitutes humanity. If intelligence is not simply a matter of size, but of adaptation, cooperation, and survival, then maybe our definition of what it means to be human is not static, but informed as much by those who have gone before us as by those who share the earth with us today.

References:

[de Robillard, Benita. 2018]. In/On the Bones: species meanings and the racialising discourse of animality in the Homo naledi controversy. Image & Text, (32), 1-26

[Sample, I. 2017] New haul of Homo naledi bones sheds surprising light on human evolution. The Guardian.

[Lisa Hendry, 2018] Homo naledi, your recently discovered human relative, Natural History Museum