Sacred Femininity and Symbolic Identity: Upper Paleolithic Venus Figurines of Europe

- iamanoushkajain

- May 10, 2025

By Advaitaa Verma

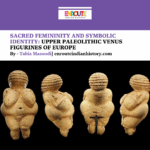

The prehistory of Europe, particularly the Upper Palaeolithic (c. 50,000–10,000 BP), marks a transformative period in human cultural and cognitive evolution. This era witnessed the spread of refined lithic industries, symbolic behavior, and artistic expression. Among the most interesting artifacts of this period are the Venus figurines (Bricker, 1976). Venus Figurines are small and exaggerated depictions of female form; gaining fascination from archaeologists and anthropologists for over a century. The figurines were discovered across Europe, spanning from France to Siberia, these artifacts date back to the Upper Paleolithic period spanning from 48,000 years ago to 12,000 years ago, providing insights into early human cognitive ability, artistic expression, and societal structures (Dixson, 2011).

The figurines, dated between 40,000 BCE and 10,000 BCE, are often crafted from materials such as stone, ivory, and clay, and are small in size ranging from 2.5 cm to 10.2 cm. These figurines exhibit a distinctive emphasis on female anatomical features, particularly those associated with fertility, maternity, and nourishment (Rice, 1981). Their presence in various prehistoric settlements raises fundamental questions: Were these figurines sacred objects linked to fertility cults or religious practices? Did they serve as educational tools for pregnancy and childbirth? Or

were they created as expressions of self-identity, social status, or aesthetic appreciation? As archaeological methods and interdisciplinary approaches evolve, researchers have proposed diverse theories regarding the psychological, social, and cultural motivations behind the creation. By integrating archaeological, cognitive, and symbolic perspectives, this article traces the psychological impetus behind the creation of Venus figurines.

Gender Representation and Symbolismn Venus figurines exhibit a striking degree of stylistic uniformity despite being found across vast geographical distances. They often emphasize features associated with fertility such as large

breasts and wide hips, de-emphasizing facial details and limbs (Dixson, 2011). The uniformity suggests a shared symbolism, possibly linked to fertility, abundance, and the veneration of femininity. However, alternative interpretations suggest that these figurines may have been used as ritual objects, amulets, or instructional tools for midwifery and reproductive education (Rice, 1981). Looking at the Upper Palaeolithic period, the prevalence of female figurines in contrast with scarcity of male representations suggests that the female body was considered an important part of the culture and symbolism of the society. This centrality of the female body has led to diverse interpretations regarding societal structures and gender roles. Some scholars such as Marija Gimbutas (1989) propose that these figurines reflect matriarchal or egalitarian social systems, where women played pivotal roles in community organization, spiritual leadership, or economic sustenance. Other scholars such as Gordon Childe (1936) argue that these figurines represented fertility goddesses, serving symbols of the early Mother Goddess cult. In prehistoric times, where survival depended on successful reproduction and resource management, the emphasis on exaggerated reproductive traits suggests an idealized representation of fertility and survival. These features may have been exaggerated to emphasize their significance within early human communities, potentially serving as fertility totems or symbols of prosperity (Rice, 1981).

Furthermore, the minimal limbs and facial features indicate that the figurines conceptualized an abstract idea of feminism, motherhood and fertility. In some cases, the figurines were associated with fertility cults or rituals that ensured successful births and sometimes they were worn as amulets such as Venus of Hohel Fels, for protection of women during pregnancy and childbirth. Their presence in both domestic and ritualistic settings further supports the idea that they were multifaceted symbols within prehistoric European societies (Rice, 1981).

Psychological Perspectives in Figurine Production

From the psychological standpoint, the creation of Venus figurines is associated with complex cognitive ideas such as abstracts, projections, and symbolic representation. The reason behind carving these figurines could have been ritualistic or meditative practices, reinforcing social cohesion and collective identity within prehistoric groups (Rice, 1981). By tracing and understanding their widespread distribution, it is possible that these artifacts played a role in

shared cultural memory, passing down traditions and beliefs across generations. Cognitive archaeology suggests that early humans had the ability to understand complex concepts such as symbolism and abstracts, allowing them to create and use visual representations to encode and spread their cultural values across a widespread area (Rice, 1981). The process of crafting Venus figurines required not only technical skill but also an ability to conceptualize

abstract ideals, such as fertility, protection, or spiritual significance (Vandewettering, 2015). The physicality of sculpting might have strengthened the artist’s connection to the figurine's symbolic meaning, reinforcing beliefs in fertility, protection, or prosperity. Another perspective connects Venus figurines to evolutionary psychology. The exaggerated anatomical features may have been a response to innate cognitive biases favoring reproductive fitness. Dale Guthrie (2005) proposed that these figurines reflect an exaggerated idealization of

fertility cues, potentially influenced by the predominantly male viewpoint of prehistoric artists. Conversely, Leroy McDermott (1996) argued that these figurines were self-representations by women, explaining the distortion of proportions as a result of carving from a first-person perspective. If true, this would suggest a deeply personal and introspective aspect of prehistoric artistic expression.

Role of Venus Figurines in Prehistory

Interpretations of Venus figurines range widely, reflecting the complexity of prehistoric belief systems and artistic traditions. One of the most widely accepted theories is that these figurines were considered as fertility symbols, serving as talismans for reproductive success, safe childbirth, and the prosperity of human groups (Vandewettering, 2015). Their exaggerated anatomical features that are associated with pregnancy, particularly breasts, hips, and buttockssuggest an emphasis on fertility and nourishment, which were crucial concerns for survival in the Upper Paleolithic environment (Rice, 1981).

Some scholars like Gordon Childe (1936) argue that these figurines were integral to ritualistic or shamanistic practices. Ethnographic parallels suggest that such artifacts may have been used in ceremonies to invoke divine favor, ensure communal prosperity, or even facilitate trance-induced communication with the spiritual realm (Dixson, 2011). Their consistent stylistic features across different regions indicate the possible existence of a shared symbolic framework and cultural values, reinforcing the notion that they were not mere individualistic expressions but part of a larger cultural or religious tradition. Another perspective highlights the potential role of Venus figurines in social identity and gender representation. Theories such as those proposed by Randall White (1999) and Leroy McDermott (1996) suggest that these figurines were crafted by women as self-representations, serving as a means of understanding their own bodies, reproductive experiences, and societal roles. This perspective challenges traditional assumptions that prehistoric art was predominantly male- centered, instead proposing that these figurines offer a direct insight into female self-perception and agency in early human communities.

Furthermore, the widespread distribution of Venus figurines across Europe, found in diverse contexts such as caves, settlements, and burials suggests that they played a multifaceted role in prehistoric society (Dixson, 2011). The figurines may have served as instructional tools for midwifery and reproductive health, could have been made into amulets for protection against dangers during pregnancy, or even markers of social status within early human groups. Few of the interesting and well-studied Venus figurines discovered from Europe are:

● Venus of Hohle Fels: It is the oldest known Venus figurine, dated between 40,000 to 35,000 years old, found in a cave named Hohle Fels in Schelklingen, Germany in 2008. This particular figurine, made from wooly mammoth ivory, has a loop instead of a head, suggesting that it was used as amulet as protection during childbirth and throughout pregnancy (Stannard & Langley, 2021).

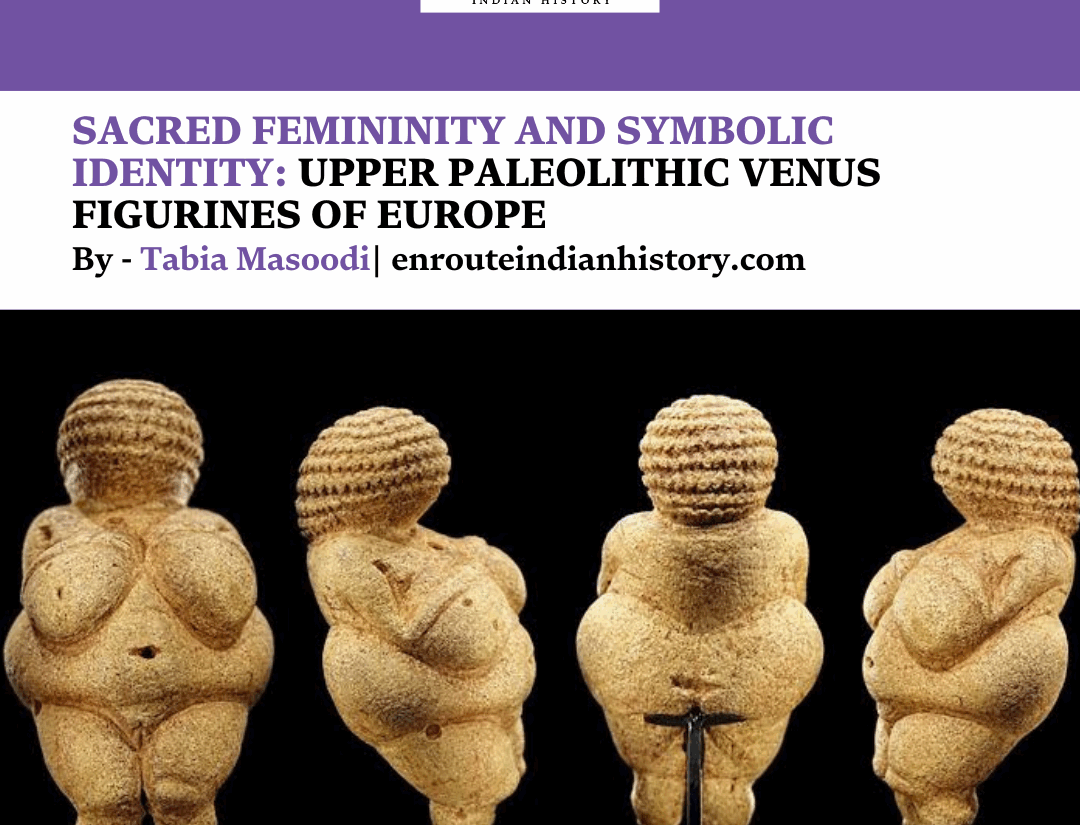

● Venus of Willendorf: It is an 11.1 centimetres figurine, made from limestone and is dated to be around 25,000 years old. It was discovered from a village named Willendorf in Austria. The figure has no visible face, her head being covered with circular horizontal bands of what might be rows of plaited hair, or perhaps a type of headdress (Dixson,

2011).

● Venus of Laussel: This figurine is a rare example of a bas-relief prehistoric art, and is a 46 centimetres bas-relief sculpture, found in France in 1911. It is carved into limestone and painted with red ochre. The figure holds a bison horn, or possibly a cornucopia, in one hand, which has thirteen notches. She has large breasts, a great stomach, and wide hips. There is a "Y" on her thigh and her faceless head is turned toward the horn (Dixson,

2011).

The Venus figurines of prehistoric Europe serve as a profound testament to early human cognition, artistic expression, and gender conceptualization. While their precise function remains elusive, their symbolic richness reveals a deep-rooted preoccupation with fertility, survival, and social identity. The gendered symbolism of Venus figurines provides a glimpse into how early humans perceived and valued the female form, either created by women as self-representations or by men as idealized depictions, these figurines remain powerful artifacts that reflect the

intricate intersection of gender, survival, and spirituality in prehistoric Europe. Analyzing the psychological processes underlying the creation of Venus figurines, we gain valuable insight into how early humans used symbolic representation to navigate their world. Whether crafted as expressions of fertility, spiritual devotion, or self-identity, these figurines reveal the intricate interplay between cognitive evolution, artistic creativity, and cultural spread

in prehistoric Europe. The enduring mystery of Venus figurines underscores their deep cultural significance, whether functioned as religious icons, fertility symbols, social markers, or tools of self-representation, their presence across prehistoric Europe highlights the profound ways in which early humans engaged with symbolic thought, gender identity, and the natural world. Ultimately, the enduring mystery of Venus figurines underscores their deep cultural significance. Whether they functioned as religious icons, fertility symbols, social markers, or tools of self- representation, their presence across prehistoric Europe highlights the profound ways in which early humans engaged with symbolic thought, gender identity, and the natural world.

References

Bricker, H.M., 1976. Upper palaeolithic archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 5,pp.133-148.

Dixson, A.F. and Dixson, B.J., 2011. Venus figurines of the European paleolithic: symbols of fertility or attractiveness?. Journal of Anthropology, 2011(1), p.569120.

Gimbutas, M., 1974. The gods and goddesses of old Europe: 7000 to 3500 BC myths, legends and cult images (Vol. 4). Univ of California Press.

McDermott, L., 1996. Self-representation in Upper Paleolithic female figurines. Current Anthropology, 37(2), pp.227-275.

Nesbitt, S., 2001. Venus figurines of the Upper Paleolithic. The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, 9(1).

Rice, P.C., 1981. Prehistoric venuses: symbols of motherhood or womanhood?. Journal of Anthropological Research, 37(4), pp.402-414.

Snijdelaar, T., 2018. Venus Figurines. Anthropos, (H. 2), pp.661-674.

Stannard, M.K. and Langley, M.C., 2021. The 40,000-Year-Old Female Figurine of Hohle Fels: Previous Assumptions and New Perspectives. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 31(1), pp.21- 33.

Vandewettering, K.R., 2015. Upper paleolithic venus figurines and interpretations of prehistoric gender representations. Pure insights, 4(7).