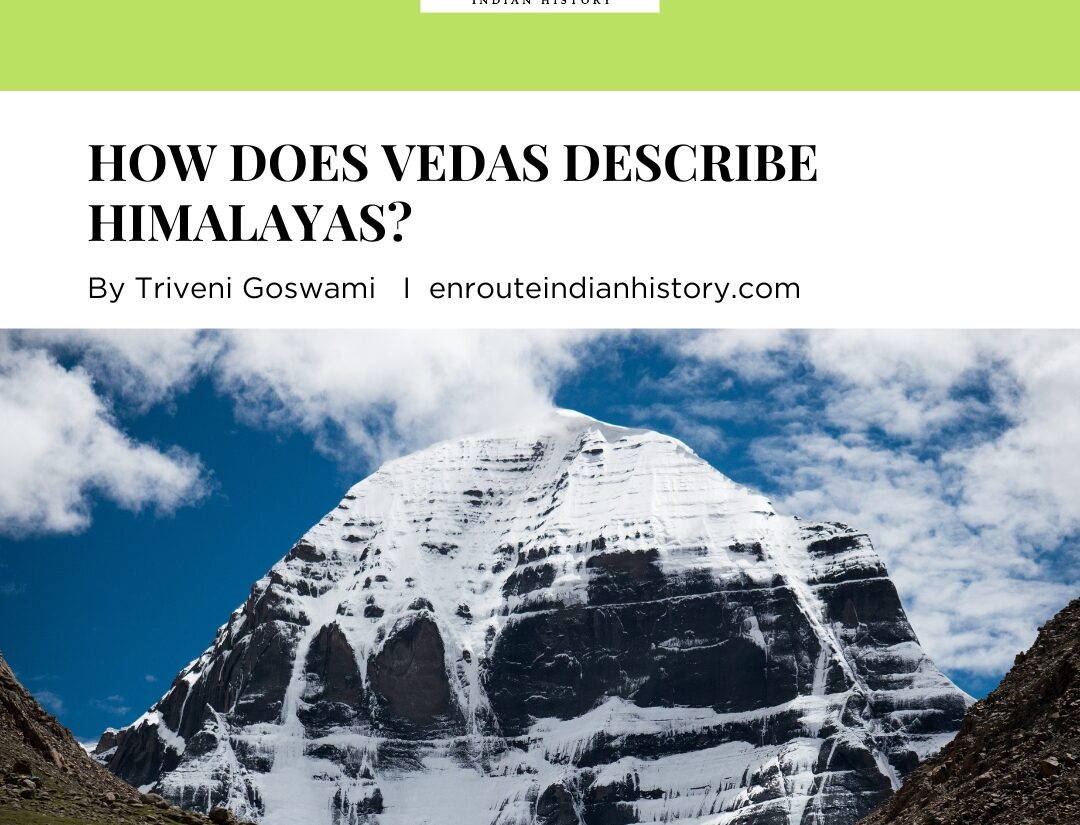

Samaveda is a Hindu scripture in the Vedic Sanskrit language.

India is a land of music. It is the warp and woof of her life and being. It is the quintessence of her culture and philosophyy. It sums up the genius of a people rich in tradition and fine arts. With this Indian music, one of the world’s oldest and most complex musical traditions, encompasses a wide variety of styles and genres. Its origins can be traced back thousands of years, with a rich history that has evolved through various cultural, religious, and social changes. In the rich tapestry of Indian culture, music holds a profound significance. It is not merely an art form but a spiritual journey, deeply rooted in ancient scriptures and traditions. It is rooted in ancient scriptures and spiritual practices that has been a profound expression of the country’s cultural heritage. Since back to the ancient times and up till today, Indian music is deeply ingrained in the daily lives of people across the Indian subcontinent, serving as a constant companion in various rituals, celebrations, and mundane activities.

There are many literary sources which shows the existence of the rituals and practices that happened during the early centuries. The most infamous source that many historians and scholars look into are the Vedas which were composed between approximately 1500 and 500 BCE. The Vedas are a major source of religious texts from ancient India and are considered as the oldest surviving text in the Indian subcontinent. Originally written in Sanskrit language, it has shown various dimensions in it. The word Veda comes from the root vid (literally, ‘to know’) and means ‘knowledge’. Brahmans, which was the most superior section of the ancient Indian society, were mostly authorised to use this text and divided the vedas to four which are enumerated: the Rigved, Yash or Yajur ved, the Saman or Sama-ved and Atharvana or Atharva-ved. Of the other three vedas each has its peculiar characteristics although they have much in common and are apparently of different dates. The Rigved, one of the oldest text, consists of a collection of 1028 hymns (arranged in 10 books called mandalas) and metrical prayers dedicated to various deities whereas the Sama ved, consisting of 1810 verses, is primarily a collection of melodies and chants, playing a crucial role in the liturgical and ritual practices of ancient Vedic religion. The Yajur Ved deals with the compilation of prose mantras and ritual instructions intended for use in the performance of Vedic sacrifices. The Atharva Ved is the latest veda and contains hymns (some from the Rigved) but also spells and charms which reflects the aspects and popular beliefs and practices. Together, these texts encapsulate the diverse aspects of early Vedic life, blending religious practices with philosophical inquiry and practical knowledge. They are crucial for understanding the historical, cultural, and religious evolution of ancient India. As we know that the rigved was divided into 10 mandalas, these mandalas consisted of different suktas and mantras which focuses on the masculine point of view. Masculinity in the Vedas is depicted through a complex interplay of traits, roles, and behaviors that are associated with male deities, reflecting an idealized form of male virtue and power that significantly influenced Vedic society. The Rigveda, for instance, extols gods like Indra, Agni, and Varuna, who embody strength, valor, wisdom, and leadership. These attributes were held as the masculine ideal, shaping societal expectations for men. Indra, the warrior god who conquers demons and protects the cosmos, exemplifies bravery and martial prowess, qualities highly esteemed in Vedic culture. Agni, the fire god, represents purity, sacrifice, and the sustainer of life, underscoring the role of men in maintaining social and cosmic order through ritual. These divine archetypes reinforced a patriarchal structure where men were seen as leaders, protectors, and providers, roles that were culturally and socially institutionalized.

During Vedic period, music was used liberally for religious ceremonies and social occasions. The music used for Yajnas (Vedic) was bound by strict rules, whereas that used for social occasions (Laukik) was according to the interests of people. Since Vedic Richas or Mantras were considered as energising, powerful and divine, they were sung at various yajnas using different procedures and methodology for fulfilling wordly and spiritual desires. Keeping this factor in mind, such Brahmins were considered as suitable for the purpose who were good singers with a naturally melodious voice, good instrumentalists and experienced in the knowledge of Vedas and Vedic rituals. Apart from these qualities, it was essential for them to receive training orally in Vedic knowledge. For Yajnas and religious ceremonies, Brahmins were given specific training in music. This training was given from father to son, Guru to Shishya, or to students of a Gurukul in a group. Ashrams and Samaparishads were established to gain knowledge of characteristics of melody and pronounciation in music. This rule bound Vedic music can be called the classical form of music of Vedic period. In the backdrop of Laukik music, Lok Gathas and songs in praise of brave men and kings such as ‘Gathas’, ‘Narashansi’, ‘Raibhya’ etc., that were used both for religious and social ceremonies were prevalent. Since the singers of ‘Gatha’ sang along with the Veena instrument, they were called ‘Gathagayak’, ‘Veenagathin’ or ‘Veenaganagn’.

SAMVED AND THE INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC

The origin of Indian music can be dated back to the ancient times but some cave paintings indicated that music emerged way before any written records were available! Some of the artifacts and caves found in certain regions of India give light to the presence of music during those times. The Bhimbetka rock caves stands as a great example for this. The caves have artworks which depicts a group of people dancing and few others holding a drum like instrument indicating that dance music and chants were an significant part of the stone age era. During that period, coming back to the ancient times, music was the medium for prayer in religious ceremonies as well as entertainment and social occasions. The development of notes originated in the Vedic period itself. Initially three Vedic notes were used-Udatta, Anudatta and Svarita. Later, they developed into seven Vedic note which finally gave way to the Laukik or Gandharva notes. Various musical instruments were also used during the Vedic period. Among stringed instruments, different types of Veena were prevalent. Also, leather instruments such as Dundubhi, wind instruments such as Tunava and metallic instruments such as Aghati were prevalent during that period. By this we get to know that Indian classical music dates back to the Vedic age (1500-500 BCE). It was deeply intertwined with religious rituals and chants, particularly the Samaveda, which laid the foundation for Indian classical music. Among the four Vedas, Sama Veda represents music. Unlike the Rigveda, which is more focused on the poetic aspects of the hymns, the Samaveda emphasizes their musical rendition. For this reason, Sama Veda has been called the origin of Indian music and has been considered as foremost among the four Vedas. As Lord Krishna has said in the Gita – ‘Vedanam samavedo’smi. Sama is sung on the basis of Richas, i.e. when the Rig Vedic Mantras are sung melodiously, they are called Sama. According to ‘Chhandogya Upanishad’, ‘Sama’ has been derived from ‘Sa’ + ‘amah’. ‘Sa’ denotes Richa and ‘amah’ demotes Alap, i.e., singing of Richas along with Alap. Therefore the singing of Vedic Mantras with melody and rhythm is called Sama Gana. So primarily, Sam Ved considered as a liturgical text, consists of melodies (sāman) and chants designed for the performance of the Soma sacrifice. It is distinct from other Vedas due to its emphasis on musical form, making it a foundational text for Indian classical music. The hymns of the Samaveda were not merely recited but sung, with specific melodies (ragas) and rhythms (talas) to enhance their spiritual potency and ritualistic importance. Raga and tala, the two fundamental concepts of Indian classical music, find their earliest expressions in the Samaveda. Raga refers to the melodic framework that allows for improvisation while adhering to certain rules regarding the scale, notes, and their arrangements. Tala, on the other hand, is the rhythmic aspect, defining the time cycle and the beat structure. The musical recitations of the Samaveda laid down the foundation for these concepts by integrating specific melodic patterns and rhythmic cycles into the hymns.

Sama Veda has two parts – Archik Sanhita and Gana Sanhita. Archik Sanhita again has two parts Purvarchik and Uttararchik. In Purvarchik, Sama Gana is done solo using a single Richa, whereas in Uttararchik, it is done using groups of three Richas. Along with the main singer, other singers are also present in this. In this way, the Richas or Mantra was prominent in Purvarchik and Uttararchik. However, with the passage of time, an increase in religious rituals saw a simultaneous rise in prominence of melody and the second part of Sama Veda, Gana Sanhita came into being. Though it was based on Archik Sanhita, the element of melody was given priority. There are four parts of Gana Sanhita – Gramageya Gana, Aranyageya Gana, Uha Gana and Uhya Gana. In Gramageya Gana, easier metre bound Sanskrit language was used instead of difficult Vedic use. Aranyageya Gana was meant to be sung in wilderness. Uha and Uhya Gana both were considered as secret forms that could only be sung by one who could decipher the meaning of Upanishads. Thus, Archik consisted of the literary aspect and Gana consisted of the melodic aspect of Sama. For the purpose of singing in Yajnas, Same Gana has been divided into five or seven Bhaktis. Five bhaktis are:

(1) Prastava

(2) Udgeeth

(3) Pratihar

(4) Updrava

(5) Nidhan.

Two other are used in some Samas, they are ‘Hinkar’ and ‘Pranava’. The Brahmins who were designated to sing these Bhaktis according to set rules were referred to as Prastota, Udgata and Pratiharta.

THE CLASSICAL MUSICAL NOTES

The Svaras (Musical Tones)

In the beginning, only three Svaras (a general term that refers to tone in singing and chanting) were used for Sama Gana, viz – Udatta, Anudatta and Svarita. Udatta denoted high, Anudatta low and Svarita was medium, in which there was a combination of high and low. To indicate these three Svaras, the numbers 1, 2 and 3 were used for Udatta, Anudatta and Svarita respectively above syllables of Mantras. The usage of Udatta, Anudatta and Svarita Svaras gave rise to three fold structure of Sama Gana – Archik Gana, Gathik Gana and Samik Gana. When only one note was used, it constituted Archik, when two notes were used it constituted Gathik and when three notes were used it constituted Samik. According to ‘Tattariya Pratishakhya’, slowly from these three notes, seven Sama Vedic Svaras developed. They were – Krushta, Prathama, Dvitiya, Tritiya, Chaturtha, Mandra and Atisvarya. They are comparable to the Laukik Svaras Ma, Ga, Re, Sa, Dha, Ni, Pa respectively.

Saraswati (who is often depicted as the goddess of music) on a Lotus throne playing veena, sandalwood, Mysore, 18th century CE

In terms of instruments, four types of instruments have been mentioned during Vedic period – (1) stringed instruments (2) wind instruments (3) leather instruments (4) metallic instruments. These four types of instruments were later called Tata, Sushir, Avanadya and Ghana instruments. Among stringed instruments of Vedic period, Veena held a prominent place. These were different types of Veena such as, Bana Veena, Karkari Veena, Kanda Veena, Apghatalika, Godha Veena etc. Bana Veena was also called Maha Veena’. It consisted of hundred strings During Mahavrat Yajna, this Veena was played using a wooden stick. Among wind instruments the name ‘Tunava’ has been used often for flute. Nadi was another synonym for flute Among leather instruments, Dundubhi and Bhumi-Dundubhi were specifically important. Dhundubhi was a type of drum which was made by stretching leather over wood and was played using a stick. This was called ‘Ahanan’. Bhumi-Dundubhi was made by digging a pit in the ground and covering it with leather. It was played using the tail of an or. Panava, Pinga, Godha, Patah and Gargar etc. were instruments of this category. A category by the name of Gadak was also present. In metallic instruments, the name of Aghati finds mention, which has also been considered the same as Apghatalik and Kanda Veena according to some view points.

Plaque with a dancer and a vina player, 1st century B.C.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, renditions of Vedic music can be seen in various traditional and contemporary settings, both within India and internationally. One prominent area where Vedic music thrives is in religious and spiritual ceremonies, particularly within Hindu temples and during important rituals such as weddings, yajnas (sacrificial rituals), and festivals. The recitation of the Vedas, including the melodious chanting of the Samaveda, is integral to these ceremonies, preserving the ancient oral traditions. Beyond religious settings, Vedic music has also found a place in the realm of academic and cultural preservation. Institutions like the Vedic Pathashalas (traditional Vedic schools) and modern universities offer courses and conduct research dedicated to the study and practice of Vedic chants, ensuring the transmission of this ancient knowledge to future generations. Additionally, classical music schools are also established to understand the elements of Vedic music into their performances and compositions, highlighting its influence on Indian classical music and also teaches the concepts of Raga, Talas and the use of other musical instruments like veena and the flute. In the global context, Vedic music has gained recognition through the efforts of cultural ambassadors and artists who perform at international festivals, yoga retreats, and spiritual gatherings. These events provide platforms for the global audience to experience the meditative and sacred qualities of Vedic chants. The digital era has further amplified the reach of Vedic music through recordings, online streaming platforms, and social media, making it accessible to a broader audience and facilitating its preservation and propagation in contemporary times.

CONCLUSION

In this period, music had a respectful place in society. Indian culture of Vedic era consisted of four Vedas – Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda and Atharva Veda. When the Mantras of Rig Veda were sung melodiously, they were called Sama.The two parts of Sama were called ‘Archik Sanhita’ and ‘Gana Sanhita’. In the beginning, the Svaras used for Sama were Udatta, Anudatta and Svarita. Later, these Svaras developed into seven Vedic Svaras. Slowly, these seven Svaras gave way to Laukik or Gandharva Svaras. During Vedic period the development of fourfold instruments had taken place. Among them, Veena, Dundubhi etc. were some such prominent instruments that were used along with Sama Gana during Yajna ceremonies. Thus, from the aspect of development of music, the Vedic period was very prosperous and sophisticated that later enriched the cultural heritage of Indian music. The Samaveda stands as a timeless testament to the foundational role it plays in both the musical traditions and everyday life of India. Its intricate hymns and melodies, meticulously preserved over millennia, have not only shaped the contours of Indian classical music but also permeated the spiritual and cultural fabric of the nation. In music, the Samaveda’s influence is profound and multifaceted. It introduced the concept of raga and tala, laying down the framework that governs improvisation, composition, and rhythmic intricacies in Indian classical music. These principles continue to guide musicians, enriching performances with their emotive depth and structured elegance. Beyond music, the Samaveda’s chants hold a deeper significance in everyday life. They are integral to religious ceremonies, invoking spiritual energies and fostering a sense of devotion and reverence. The rhythmic recitation of Vedic hymns not only preserves ancient linguistic and phonetic traditions but also serves as a conduit for communal harmony and cultural continuity. Ultimately, the Samaveda’s foundation in music and everyday life underscores its enduring significance as a cultural treasure, resonating through generations with its profound spiritual resonance and artistic innovation. It remains a cornerstone of India’s cultural identity, offering a timeless bridge between the ancient past and the dynamic present.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Mansukhani Singh Gobindh. Indian Classical Music and Sikh Kirtan, 1982.

- Wilson HH, Rigveda-Sanskrit, vol 18

- Doniger. Wendy, The Rigveda: An anthology. Penguin classics, 1981.

- Sharma, Manorama. The Making of a Musical Tradition: The Role of the Samaveda in Indian Music. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1992.

- Nijenhuis, Emmie te. Indian Music: History and Structure. Brill Archive, 1974.

- Subramaniam, L. Indian Music: The Magic of the Raga. South Asia Books, 1999.

- The national institute of open learning, BRIEF STUDY OF MUSIC IN VEDA WITH SPECIAl REFERENCE TO SAMA VEDA

- Samaveda, Wikipedia