Sarojini Naidu: The Nightingale’s Song of Freedom

- iamanoushkajain

- August 16, 2024

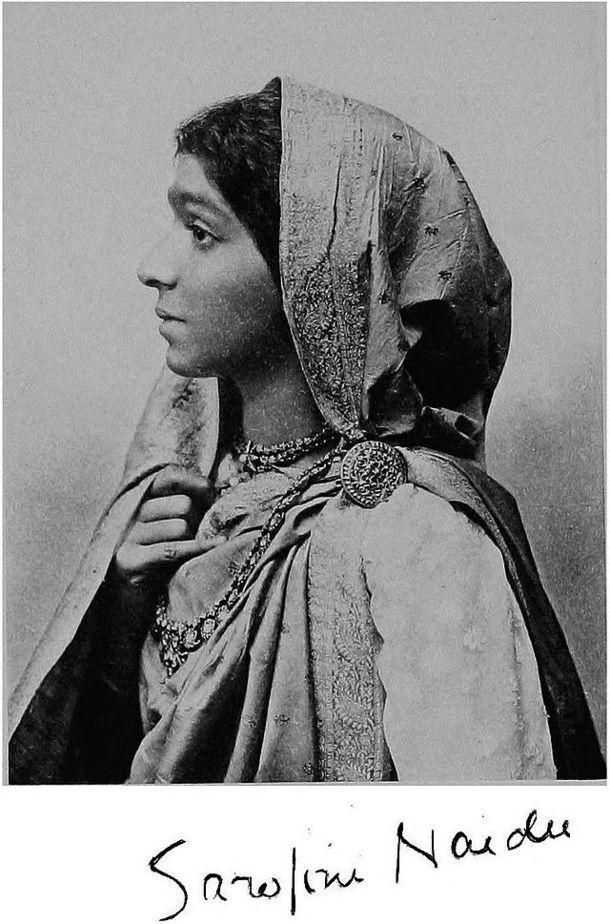

Famously referred to as Bulbul-i-hind, or the “Nightingale of India,” Sarojini Naidu (1879–1949) was an extraordinary person who skillfully combined her positions as a nationalist politician and an English-speaking Indian poetess. Her art and life represented a distinct brand of cosmopolitan nationalism that skillfully balanced the many conflicts between the burgeoning Indian nationhood and colonial oppression.

Sarojini Naidu

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, women’s participation in public life increased, albeit within often patriarchal boundaries, as the Indian nationalist movement against British colonial rule strengthened. Sarojini Naidu became a well-known voice in this milieu, using her oratory prowess and poetic gifts to further the cause of women’s rights and Indian independence.

(Sarojini Naidu in 1912, source: Wikimedia Commons)

(Sarojini Naidu. source: Google Photos)

Sarojini Naidu : Political Career

Naidu’s political involvement grew steadily over the years. She actively participated in the Indian National Congress and served as its president in 1925. With Mahatma Gandhi as her leader, Naidu contributed to the non-cooperation movement and the civil disobedience movement. She was arrested several times for her involvement in these protests, including in 1930 during the Salt March, when she led the protestors after Gandhi was arrested.

(Sarojini Naidu with Mahatma Gandhi in Salt March, 1931, source: Express Archive)

Her leadership in the Quit India Movement of 1942 further cemented her status as a national leader. Despite her reputation, Naidu faced significant challenges, such as the difficulty of juggling her roles as a poet and a politician, as well as gender biases that prevented women from participating in the independence movement.

Sarojini Naidu’s unwavering efforts culminated in India’s independence in 1947, and she was the first woman to hold the office of governor of the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). Throughout her career, she used her oratorical skills to advocate for Indian independence, Hindu-Muslim unity, and women’s rights. Naidu played a crucial role in conceptualizing women’s engagement in the nationalist movement. In 1918, Naidu and other British and Indian feminists launched the magazine “Stri Dharma” with the goal of presenting world events from a feminist standpoint. She also championed women’s participation by emphasizing their “essential” qualities of spirituality. and nurturing capacity. In a 1916 lecture to the Hindu Ladies’ Social and Literary Club of Bombay, she declared:

“The real test of nationhood is the woman… In India, this problem can be solved by bringing upon the woman a sense of responsibility and impressing upon her the divinity and conscientiousness of her power and work as motherhood. The work of nation-building must begin from the woman unit.”

(Sarojini Naidu with Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru and Edwina Mountbatten, Source: Getty Images)

While this rhetoric aligned with the prevailing nationalist discourse on women’s roles, Naidu pushed boundaries by advocating for women’s education and suffrage. In a 1906 speech, she stated:

“It is ironical that we have to plead for women’s education in the early twentieth century in all places in India, which, at the beginning of the first century, was already ripe with civilization and had contributed to the world’s progress as radiant examples of women of the highest genius and widest culture.”

(The wire, Sarojini Naidu in London, 1930)

Naidu’s Nationalist Poetry

Naidu’s political career was intricately linked to her poetic endeavors. As she wrote in a 1905 letter to Edmund Gosse, explaining her decision to publish her first collection of poems:

“To my great amazement – it was nothing less – so far from being the insignificant little provincial I had thought myself I was treated almost as a national possession. I!”

This realization of her fame at the 1904 Indian National Congress meeting in Bombay spurred her to embrace her role as a “national poet.” She saw it as her duty to serve the Indian public through her art, writing: “My public was waiting for me – no, not for me, so much as for a poet, a national poet, and it was ready to accept me if I would only let it.”

(Sarojini Naidu giving a speech; Naidu was famous for her impassioned speeches, which inspired the people of India; source: The Indian Express)

Naidu’s verses often blended nationalist themes with romantic imagery drawn from both Indian and Western traditions. Sarojini Naidu’s renowned poetic compilations include “The Golden Threshold” (1905), “The Bird of Time: Songs of Life, Death, & the Spring” (1912), “The Broken Wing: Songs of Love, Death and the Spring” (1917), “The Sceptred Flute: Songs of India” (1928), and “The Feather of the Dawn” (1961, posthumous).

One of her most powerful nationalist poems, “The Gift of India,” written during World War I, critiques the British Empire’s exploitation of Indian soldiers:

“Is there aught you need that my hands withhold,

Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold?

Lo! I have flung to the East and West

Priceless treasures torn from my breast,

And yielded the sons of my stricken womb

To the drum-beats of duty, the sabres of doom.”

The poem personifies India as a mother who has sacrificed her sons for an ungrateful empire, highlighting the injustice of colonial rule while also emphasizing Indian valor and sacrifice.

Another poem of hers that stirs up nationalist sentiment, “Awake” is an appeal for Indians to get up and fight for their freedom, and it is dedicated to Gopal Krishna Gokhale. It highlights how urgent the nationalist movement is and how teamwork is required to win freedom.

Excerpt:

“Take up the challenge from the fields of death,

men of my land, and rise in sacred faith!

The cry of mothers’ hearts is in your ear,

and the trumpet of the brave has sounded clearly.”

This poem is a call to action for Indians, imploring them to get out of their sleep and assume leadership roles in the liberation movement.

Through a combination of her literary sensitivities and her nationalist enthusiasm, Naidu conveys her profound love for her country in this poem titled “The Song of India.” The poem is a tribute to India, praising its natural beauty and cultural legacy while advocating for its independence from colonial domination.

Excerpt:

“O, warrior nation with banner and spear,

O youthful republic on the heights of the morning,

Give us your limbs so we can drain you of

your vital force until India’s cause is resolved and unambiguous.”

The poem’s imagery conveys Naidu’s idea of a free and powerful India that stands tall among the republics of the world.

Another poem, “An Anthem of Love,” which is less well-known, combines Naidu’s nationalist views with her romantic style. It expresses her conviction that love and unity can triumph over the obstacles confronting the country.

An excerpt from the poem reads,

“Sing the love that is strength of strife,

The courage of faith in the mind of youth,

Sing the love that is the life of life,

The power of truth!”

The poem is a call to action as well as a celebration of love, encouraging Indians to cherish love in order to achieve independence and national unity.

The palanquin bearers

“Lightly, O lightly we bear her along,

She sways like a flower in the wind of our song;

She skims like a bird on the foam of a stream,

She floats like a laugh from the lips of a dream.”

This poem can be read as a metaphor for the burdens India carried during colonial control, even though it appears to be focused on a traditional Indian scenario. The palanquin carriers’ rhythmic movement symbolizes the Indian people’s tenacity and continuous battle.The poem delicately captures India’s fortitude and grace in enduring colonial persecution.

Naidu’s skill at incorporating nationalist ideas into her portrayal of ordinary Indian life is demonstrated once more in this poem, “Coromandel Fishers.”

Excerpt:

“Rise, brothers, rise; the wakening skies pray to the morning light,

The wind lies asleep in the arms of the dawn like a child that has cried all night.

Come, let us gather our nets from the shore and set our catamarans free,

To capture the leaping wealth of the tide, for we are the sons of the sea.”

The fisherman in the poem represent the Indian people, who had to sail across the rough waters of colonial tyranny in order to achieve freedom.

In yet another poem,

“I dreamed a dream, but it has fled from me,

Like the light of a ghostly moon;

It has gone like a silent bird to its nest,

In the night’s dark heart alone.”

Naidu muses on the dashed hopes of liberation with a gloomy tone that portrays the agony and loss endured by those who battled for India’s freedom. It is possibly alluding to the struggles and setbacks faced by the nationalist movement. It is a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made in the pursuit of independence.

To India

“O young republic on the hills of the dawn,

O ancient of the days of the sun,

I sing of the glory of thee!”

Naidu expresses her love and commitment to her motherland clearly in this poem. Her aspirations for a liberated and thriving India are reflected in it.

(Cover of “Sarojini Naidu her way with words, 2013”; source: wikicommons)

The “Nightingale of India” Title

Naidu earned the title “Nightingale of India” for her lyrical poetry and powerful oratory. Her ability to blend English poetic forms with Indian themes and imagery captivated audiences both in India and abroad. However, this title was double-edged. While it brought her fame, it also led some critics to dismiss her work as merely decorative or romantic, underestimating its political significance.

Naidu was acutely aware of the tension between her roles as poet and politician. In a 1918 speech, she addressed this directly:

“Often and often have they said to me: ‘Why have you come out of the ivory tower of dreams to the market place? Why have you deserted the pipes and flute of the poet to be the most strident trumpet of those who stand and call the nation to battle?’ Because the function of a poet is not merely to be isolated in ivory towers of dreams set in a garden of roses, but his place is with the people; in the dust of the highways, in the difficulties of battle, is the poet’s destiny.”

The life and works of Sarojini Naidu represent a distinct kind of cosmopolitan nationalism that aimed to balance India’s modern goals with its ancient heritage. Her passion for India’s liberation and advancement was interwoven with both her political activism and poetry.

“Now I am glad to set my face homewards once again to serve India with speech, song, and struggle,” she wrote in a letter from Marseille in 1921. This emotion, which Naidu communicated through the combined media of politics and poetry, captures her lifelong devotion to her country. Even today, The Nightingale of India’s song continues to resonate, reminding us of the power of words to inspire change and the possibility of bridging cultural divides in the pursuit of freedom and equality.

(Naidu on an Indian stamp, showing her received respect from the contemporary Indian public,

source: http://colnect.com/en/stamps/stamp/371659-Sarojini_Naidu_1879-1949-Personalities-India)

REFERENCES

Dutt, Toru. Ancient Ballads and Legends of Hindustan. Edited by Edmund Gosse, K. Paul, Trench, 1882.

Gosse, Edmund. “Introduction.” The Bird of Time: Songs of Life, Death and the Spring, by Sarojini Naidu, William Heinemann, 1912.

Kumar, Radha. The History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India 1800-1990. Kali for Women, 1993.

Mishra, L. N. The Poetry of Sarojini Naidu. B. R. Publishing, 1995.

Naidu, Sarojini. Speeches and Writings. Natesan and Company, 1918.

Naidu, Sarojini. The Sceptered Flute: Songs of India (The Collected Poems of Sarojini Naidu). Dodd, Mead and Company, 1928.

Naidu, Sarojini. The Golden Threshold. Introduction by Arthur Symons, William Heinemann, 1909

Naidu, Sarojini. Sarojini Naidu: Selected Letters, 1890s to 1940s. Edited by Makarand Paranjape, Kali for Women, 1996.

—. Speeches and Writings of Sarojini Naidu. 3rd ed., G. A. Natesan, 1925.

Sengupta, Padmini. Sarojini Naidu: A Biography. Asia Publishing House, 1966.