Sheherwali Cuisine What does the vegetarian heritage of Murshidabad look like?

- iamanoushkajain

- June 6, 2024

A Confluence of Cultures

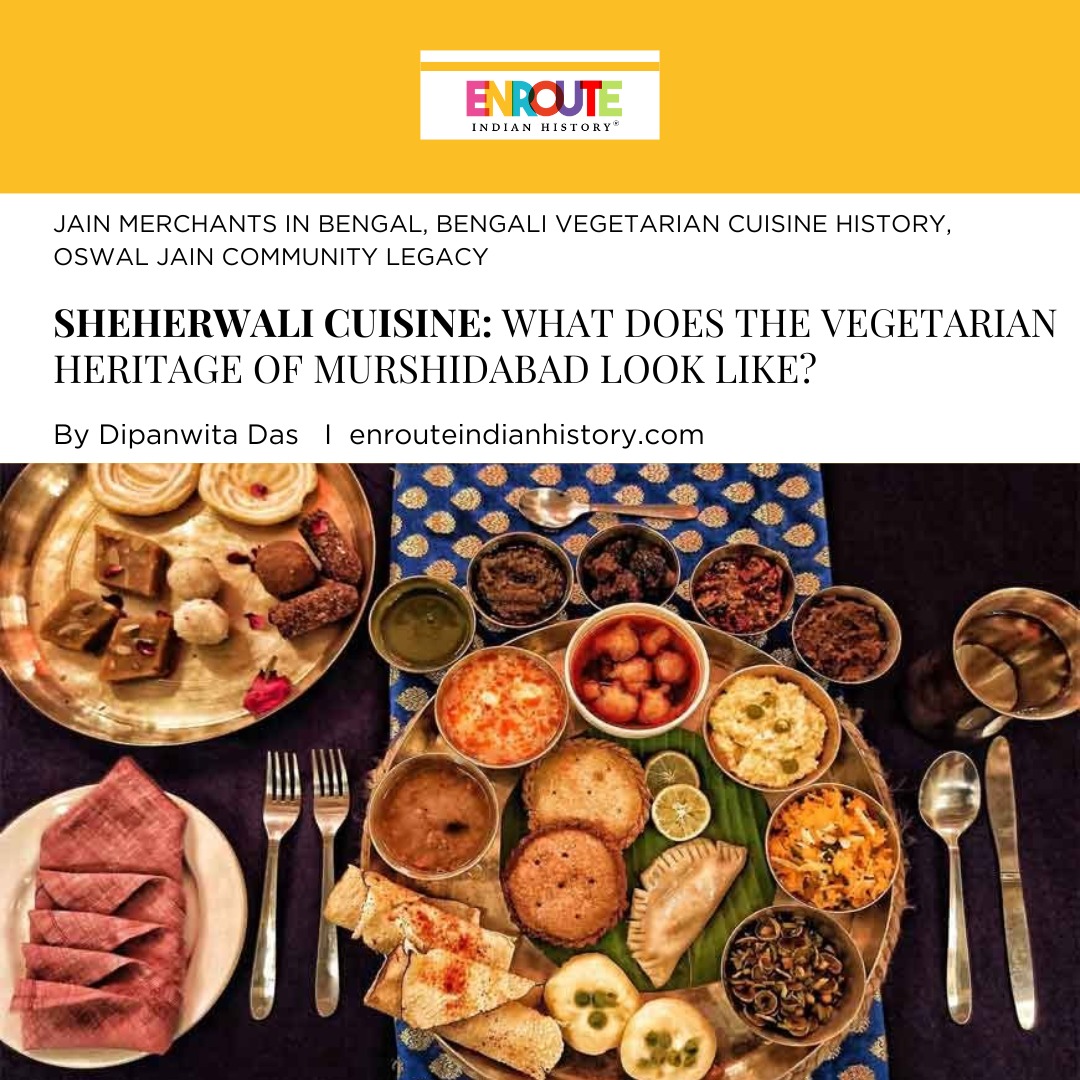

For ages, Bengali cuisine has been synonymous with Maach, Maangsho aar Mishti Doi (Fish, Meat and Sweet curd). Bengal has much more to offer than meets the eye. It boasts a rich history that dates back many years. While some historical trivia has gained worldwide fame, there are lesser-known aspects as well. One such lesser-explored facet is the Sheherwali community and their royal cuisine. Who are the Sheherwalis? About 300 years ago, in the 18th century, a group of Oswal Jain Community merchants migrated from the deserts of Rajasthan to Bengal. They settled in Murshidabad, the capital of the Nawabs of Bengal at the time. Over time, these merchants and traders became one of the most influential business communities in colonial India, leading to the flourishing of the Sheherwali culture in Bengal. The Sheherwalis wholeheartedly embraced the culture, cuisine, and lifestyle of Bengal, heavily influenced by the Nawabs of Bengal. They adopted Bengali attire and incorporated various local foods into their cuisine, creating a unique mixed culture that became a symbol of royalty in Bengal. The Sheherwali cuisine, described by the Murshidabad Heritage Development Society as “possibly the finest vegetarian spread,” is a delightful fusion of Western and Eastern Indian cuisines. The flavours of ghee-rich Rajasthani dishes combined with Bengali spices and Nawabi ingredients create a unique and rich culinary experience. The slow cooking process adds depth and richness to these vegetarian dishes. The Murshidabad Heritage Development Society, founded in 2010, is committed to preserving and reviving the heritage of Murshidabad.

(Courtesy: Kaushani Banerjee, The New Indian Express Titled: Sheherwali Thali, ITC Royal Bengal)

A Brief History

The Jagat Seth dynasty is a distinguished Oswal Jain family of Gailara Gotra in India, renowned for its remarkable influence in political, religious, and business circles. Historical records indicate that the Gailara gotra traces back to the Khichi Gahlot Rajputs in 1495 AD, when Girdhar Singh Gahlot, under the guidance of Jain Saint Jinhans Suriji, adopted Jainism. This lineage is associated with the Svetambara sect (Walsh, 1902). In 1652, Heeranand Sahu, the progenitor of the Seths, made a significant move by leaving Nagore, their ancestral home in Marwar, and embarking on a migration to Patna. With his astute business acumen, Heeranand Sahu prospered as a banker and a saltpetre trader in Patna, capitalising on the high demand for Bihar’s saltpetre among the Europeans. The resulting successes enabled him to support Europeans by providing loans and discounting bills of exchange. Heeranand Sahu had seven sons – Manick Chand, Nayan Chand, Amen Chand, Muluk Chand, Roop Chand, Sudhanand, and Gobordhan, who, upon reaching adulthood, became prominent bankers, spreading their influence across various regions in India. Noteworthy among his sons is Manick Chand, who made his mark in Dacca, the capital of Bengal. Additionally, Heeranand Sahu arranged a marriage between his daughter and a son of Uadichand. At the invitation of Manik Chand, the Oswal Jain merchant families migrated to the lush banks of the Bhagirathi river around Azimganj, Jiaganj, Lalbagh, Nashipur, and Kassimbazar – all suburbs of Murshidabad, which was then the capital of Undivided Bengal. The term “sherwani” was used for these families, who travelled from the smaller towns of Rajasthan to the bustling city of Murshidabad (O’Malley, 1914).

(Source: Duncan 1890, Titled: A group of Oswal Jain Community merchants settled in Murshidabad, www.istockphoto.com)

Rajasthan is famous for its extreme climate and water scarcity. Due to the extreme climate, food in Rajasthan had to be prepared to last for more than a day without needing to be reheated. To compensate for the shortage of water, milk and ghee were used generously, resulting in bold and spicy flavours. Fresh vegetables were not abundant, so lentils, bajra, corn, and beans were commonly used. The royal kitchens in Rajasthan popularized rare food ingredients such as rose water, saffron, food aromatics, and herbs (Banerjee, 2019). As the Oswal Jains settled in the region, they adapted to the local conditions by creating a fusion cuisine that combined techniques and rich ingredients from their homeland with the fresh, seasonal produce available locally. This cuisine included plenty of ghee and spices to compensate for the scarcity of water. When this cuisine made its way to Bengal, it integrated with local cooking practices and also incorporated flavours from the Afghans and Mughals. At that time, Bengal was a hub of trade and politics, with the presence of Portuguese, French, Dutch, and Armenian communities (Walsh, 1902). The Oswal Jain families strictly followed vegetarian practices that aligned with Jaina’s philosophy, prohibiting the use of root vegetables, onions, ginger, and garlic.

(Courtesy: Gopa Bhattacharjee, Titled: Sheherwali cuisine, the Royal Food Of Bengal, www.getbengal.com)

Delicacies

The Sheherwali cuisine is known for its no-onion-no-garlic dishes, made with ingredients like mamra khajoor, resham patti chillies, and sharbati dana wheat. Some of the unique dishes include kheera shimla mirch tarkari (cucumber and capsicum vegetable dish), maheen boondi (sweetened gram flour pearls flavoured with rose water and Pampore saffron), khatte ki pakauri (gram flour fritters in tamarind water), parwal dabdaba (pointed gourd with homemade dry spices), barbati dahi (long beans in sour yoghurt gravy), and bhutta khichdi (fresh corn kernels cooked with gobindo bhog rice using ghee). One of the popular dishes is kacche aam ka kheer, where ripe mango is mixed with kheer while maintaining its sweetness. Sheherwali cuisine is a hidden gem of Bengal, not commonly found in restaurants, but it reflects Bengal’s diverse culinary traditions (Bhattacharjee, 2021).

The Sheherwali meal includes two major and expensive ingredients: saffron and a brand of rosewater made from the Shahi Basra Aruk Gulab. This cuisine uses paanch phoron, which is typically used in Bengali food. Bengali words like jal (water), gaachh (tree), boi (book), and tarkari (vegetable) have made their way into the Sheherwali lingo as well. Sweet dishes in a Sheherwali household are not referred to as “dessert” because dessert is eaten before, during, and after a meal—there is no time that is not sweet! The signature dishes of Sheherwali cuisine are Saloni Mewa Ka Khichdi, Bode Ka Boondiya, Pitha, and Bhapia (Dey, 2012).

A Sweet Tooth!

The Sheherwalis, known for their love for sweets, have a tradition of indulging in sweet treats before, during, and after meals. This fondness for sweets is rooted in their Rajasthani heritage and influenced by the Bengali tradition of savouring sweet delicacies. As part of their breakfast customs, it is common for them to enjoy a glass of milk paired with delectable sweets such as malpua, chhana bara, or raskadam. On the other hand, the Oswal Jains have a deep affection for mangoes, particularly during the bountiful summer season. An example of their culinary expertise with mangoes is the preparation of “Kachhe Aam Ke Kheer,” a delightful mango kheer made using unripe mangoes. These mangoes are grated, boiled to remove their sourness, and then simmered in a fragrant mixture of milk, saffron, sugar, and rose water, creating a truly exquisite dessert. Take for example the “bode ke boondiya,” which is a dish of deep-fried sweet balls made from black-eyed bean flour. This recipe uses kewra water, which is of Mughal origin. Another example is sweet balls made from wheat flour, called “ghaal ka laddoo,” which uses rose water. Pumpkin is another vegetable that features in regular Bengali cuisine. The Sheherwalis took this pumpkin and, inspired by the murabba culture of the Mughals, developed the “kumra ka murabba.”

(Courtesy: Kachhe Aam Ke Kheer and Ghaal Ka Laddoo [left to right], Lesser-known dishes of Sheherwali cuisine, timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

Snacks

Savory snacks are a norm for the Sheherwalis. They made kachoris stuffed with cucumbers, a local produce, and named it “kheere ki kachori.” Sheherwalis had a particular liking for cucumbers, which is why they prepared many dishes with them. Another example is “kheere ka pitod,” where cucumbers were dunked in a batter made from gram flour and deep fried. Spiced gram flour balls are fried and dunked into a tangy tamarind syrup. This “khatte ka pakori” was provided as refreshment during the summer months. Neemas is a similar variant of Daulat Ki Chaat.

(Courtesy: Kheere ka Pitod, Neemas and Kheere ki Kachori [left to right], Lesser-known dishes of Sheherwali cuisine, timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

Main Course

Kela Parwal ka Jholgiri is a delicious curry made using plantain and pointed gourds. Note the use of the word “jhol” which is a Bengali word for a thin gravy. Kheera Shimla Mirch ka Tarkari is a unique vegetarian curry made from cucumber and capsicum. Again, the word ‘tarkari’ is a Bengali word for ‘curry’. What we call “panch torkari” or “panch mishali torkari” in Bengali (or simply mix veg) is “milao ka tarkari” in Sheherwali Cuisine. Locally grown vegetables are cooked using “panch phoron” and mustard oil. Tamarind is added to introduce tang in the dish. Paniphal ka tarkari is a unique curry that most Bengalis have never had in their lifetime. Murshidabad grows water chestnuts in some of the areas. They are sliced and cooked into a simple curry using turmeric powder, chilli powder, and aamchoor powder. Innovation at its best! Bengal gram or chana dal is used to cook curries by adding veggies like ridge gourds. This “taroi boot ka dal” uses hing like most other curries cooked in this cuisine. Another interesting recipe from the kitchen of the sheherwalis is the “mattar ke chhilke ke tarkari.” The peel from fresh peas is stir-fried with capsicum. Rajasthanis are known to cook a variety of bread that include a deep-fried bread from urad (or arhar) dal, semolina, and wheat flour called “kalai ka kachori,” “besni poori” or puffed puris made from gram flour or besan, and a shallow-fried bread stuffed with green moong dal called “bedmi.” The most intriguing bread for me is, however, the “khichdi ka roti.” Wait, what? Isn’t khichdi a rice preparation? This Sheherwali preparation is a rare example of wit and innovation. The first step involves cooking khichdi by pressure-cooking rice, moong dal, salt, and turmeric. Then wheat flour is added to it along with salt, chilli powder, coriander powder, and ghee. The entire mixture is kneaded into a dough. The dough is then cut into shapes, made into a flatbread, and roasted on a hot pan until half done. This is cooled, pinched, and then directly roasted on the fire until fully done.

(Courtesy: Khichdi Roti, Gauravi Vinay, www.archanaskitchen.com)

(Courtesy: Kheera Shimla Mirch ka Tarkari, Madhuli Ajay, www.archanaskitchen.com)

References

“Bengal’s unique Sheherwali Cuisine – the Royal Vegetarian delight of Murshidabad.” Get Bengal, www.getbengal.com/details/bengals-unique-sheherwali-cuisine-the-royal-vegetarian-delight-of-murshidabad.

“Lesser-known dishes of Sheherwali cuisine.” The Times of India, 20 Dec. 2021, timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/food-news/lesser-known-dishes-of-sheherwali-cuisine/photostory/88201678.cms.

Banerjee, Saikat, and Paroma Mitra Mukherjee. “Revamping heritage brand: a case of Murshidabad, West Bengal, India.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, vol. 18, no. 2, Mar. 2021, pp. 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-021-00202-w.

Dey, Sreyoshi “A Cookbook Turns the Spotlight on the Little-Known Sheherwali Cuisine.” Telegraph India, 6 Jan. 2012,

Kaushani Banerjee, and Kaushani Banerjee. “Another food secret laid bare: Introducing ‘Sheherwali’ cuisine.” The New Indian Express, 1 Sept. 2019, www.newindianexpress.com/lifestyle/food/2019/Aug/31/another-food-secret-laid-bare-introducing-sheherwali-cuisine-2026505.html.

O’Malley, Lewis Sydney Steward. Murshidabad. 1914, books.google.ie/books?id=GhfjAAAAMAAJ&q=Murshidabad+By+Lewis+Sydney+Steward+O%27Malley+(1914)&dq=Murshidabad+By+Lewis+Sydney+Steward+O%27Malley+(1914)&hl=&cd=6&source=gbs_api.

Varma, Shraddha, and Shraddha Varma. “A Taste Of The Cuisine Of The Sheherwali Community That Moved Cities in Colonial India.” Zee Zest, 8 Mar. 2024, zeezest.com/food/a-taste-of-the-cuisine-of-the-sheherwali-community-that-moved-cities-in-colonial-india-616.

Vishal, Anoothi. “Vegetarian cuisines of India: The food of the Sheherwali Jains from Murshidabad.” The Economic Times, 27 July 2019, economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/vegetarian-cuisines-of-india-the-food-of-the-sheherwali-jains-from murshidabad/articleshow/70413233.cms?utm_source=pocket_mylist&from=mdr.

Walsh, J.H. Tull. A history of Murshidabad District (Bengal) : with biographies of some of its noted families. Dalcassian Publishing Company, 1902, books.google.ie/books?id=zovUDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Murshidabad+-+By+Lewis+Sydney+Steward+O%27Malley+(1914)&hl=&cd=7&source=gbs_api.

Walsh, John Henry Tull. A History of Murshidabad District (Bengal). 1902, books.google.ie/books?id=Pga7-igRruUC&q=A+history+of+Murshidabad+District+(Bengal)+(1902)+-+By+John+Henry+Tull&dq=A+history+of+Murshidabad+District+(Bengal)+(1902)+-+By+John+Henry+Tull&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api.