Article written by EIH Researcher and writer

Rayana Rose Sabu

“Stories make us connect us”

–Gorrella Ramam aka Ramu

The world has changed and expanded a lot in the last several decades. Technology in every shape and form has benefited us, making our lives simpler. But, every boon has a bane, every advantage has a disadvantage, and the downside of the tech revolution is that various traditional professions are dying out. The “professionals” we formerly looked to for their expertise frequently find themselves unemployed. A sense of nostalgia looms over us when we encounter one of these people in the obscure lanes of a market.

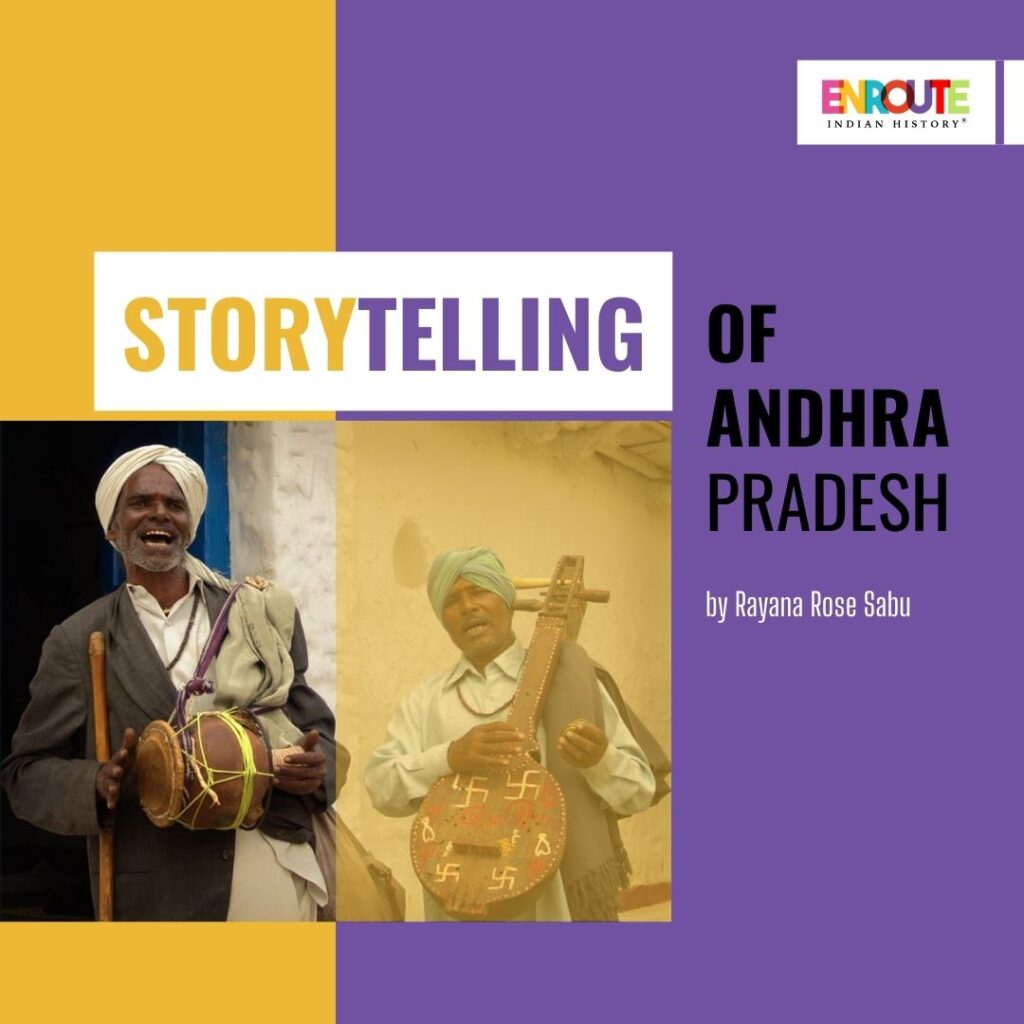

Burrakatha, or storytelling by the rural population from Andhra Pradesh, is a profession that was historically used as a weapon against feudal lords and unjust governance. “Burra” describes the tambura, a stringed instrument the musician wears across their right shoulder. Katha, meanwhile, means narrative. Kathakudu, the main performer, tells his story while playing the tambura and dancing in time to the music. On his thumb, he wears a hollow ring with metal balls within and holds one in each hand. They chime in time with the song’s basic tempo. The drummer, known as the rajkiya, stands next to the story and makes commentary on current political and social issues, regardless of whether the story is about historical or legendary events.

The Cambridge Handbook to Theatre stated that burrakatha was descended from another art form known as jangam katha, which was “considered to have originated from bands of travelling minstrels (jangam) who sung the worship of Lord Shiva as they travelled rural areas in ancient times” (1995). “The minstrels responded by including secular materials into their performances as audiences’ social and religious affiliations changed.” This is the most well-known type of folk storytelling, and it was used earlier to tell poorly educated people tales from the Puranas and the Ithihasas. They learned about their military history by listening to the accounts of “Palnati Yuddham” (the battle of Palnadu), “Bobbili Yuddham” (the battle of Bobbili), and “Desigu Raja Kathalu.” It’s a storytelling style that blends an understanding of the Puranas and lithihasas, dharma prabodha, and some fun to assist the combination in cementing itself in the minds of the general public. The traditional poetic metres “ragada” and “dwipada,” as well as “ragam” and “talam”, and the rhythmic accompaniment provided by the accompanists, are the foundations upon which the narration is built. It occasionally lasts into the wee hours of the morning and is an inexpensive form of entertainment for town squares and street corners. People would give charity to storytellers in the past, but nowadays, there is more of a set charge.

The first Burra Katha performed in Telangana, Kashtajeevi, related the story of how farmers were made to wander around with rocks strapped to their backs after they informed the dora (landlord) that they couldn’t pay tax since they had no produce that year.

Burrakatha was used in the struggle for liberation to instil patriotism in the populace. The most recent events, the leaders’ sacrifices, their plans, and the British schemes were all integrated into the stories. Burrakatha was outlawed in Madras province and Nizam’s realm due to concerns over its impact on rural residents and persons living in remote areas. The form of storytelling developed into a resounding voice that broke the quiet and suffering that rural communities had been experiencing for years during the Telangana Rebellion.

Burrakatha was utilised in the 1940s by the Indian People’s Theatre Association, which was then strongly linked to the Communist Party of India, to spread its political and social message. The Praja Natya Mandali in Andhra Pradesh, established to overthrow the Nizams during the uprising, likewise employed the arts to appeal to a large audience of voters. This tradition was introduced to the stage by Shaik Nazar, who also wrote stories about the Bengal famine, Palnati Yuddham, and Bobbili Yuddham, among other topics. For his contributions to folk art, he was awarded the Padma Shri and later inspired several generations of artists.

But as the country gained Independence, this form of storytelling changed. It started to fade away in the 1970s, and the invention of televisions seriously endangered the art. Modern governments have utilised it to raise awareness about social issues like child marriage, sanitation, and electrification, but little is known about its cultural and historical significance. The advent of the internet, which made it simple to obtain plays and movies, has only served to obscure Burrakatha further. Ramu, a Burrakatha performer, has been working to preserve this vanishing art form with his troupe. He claims, “I’ve attempted to conduct workshops to impart this art and train people to carry on the art. But it hasn’t come to pass.” He says that many are reluctant to perform on stage even after learning. Ramu believes that the field and the arts have failed to draw in enough educated individuals with language and pronunciation skills, or “vachakam,” who can tell a tale on stage with the authority of lions. He blames the television for the declining popularity of Burrakatha. “TV serials are making people get stuck there.” Apart from its entertainment value, Burrakatha is a service to the community, he says.

“People are losing the sense of community that used to be built around performances: villagers would gather, have social relationships with each other and celebrate folk art and that bound people. But now, TV is making people more and more isolated. Even in villages.”

Today’s practitioners of the craft barely make enough money to support their families, and for the majority, it is no longer their primary source of income. They earn 3000-5000 for each performance, whereas organisations and government pay much lesser. Not much has been done by the state to preserve this dying profession. Thanks to the neglect, many practitioners of this art form have switched to other jobs, and it would not be long before this magnificent vocation disappears without a trace.

SOURCES

- The good, old storytellers. (n.d.). Fountainink.in. Retrieved April 9, 2023, from https://fountainink.in/reportage/the-good-old-storytellers

- Sethu, D. (2022, March 22). Ancient Oral Storytelling Struck Fear Among the British Government. The Better India. https://www.thebetterindia.com/279853/burrakatha-ancient-oral-storytelling-dissent-tradition-india-history-british-rule-twitter-viral/

- Burrakatha loses sheen sans patronage – Times Of India. (2013, November 14). Web.archive.org. https://web.archive.org/web/20131114014507/http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2013-01-14/visakhapatnam/36332535_1_artistes-burrakatha-art-form