Sulabha’s Debate: Women Defying Gender Norms in Ancient Mythology

- EIH User

- August 30, 2024

Gender-specific norms and expectations surrounding women’s roles, skills, and moral conduct have historically and currently imposed considerable restrictions on them. Nonetheless, there have always been women who have questioned gender norms and disregarded these traditions, both in historical writings and in contemporary cultures. An inspiring example of a woman in antiquity who aggressively argued for women’s intellectual and spiritual equality and defied gendered constraints may be found in the debate between Sulabha and King Janaka in the ancient Hindu epic Mahabharata.

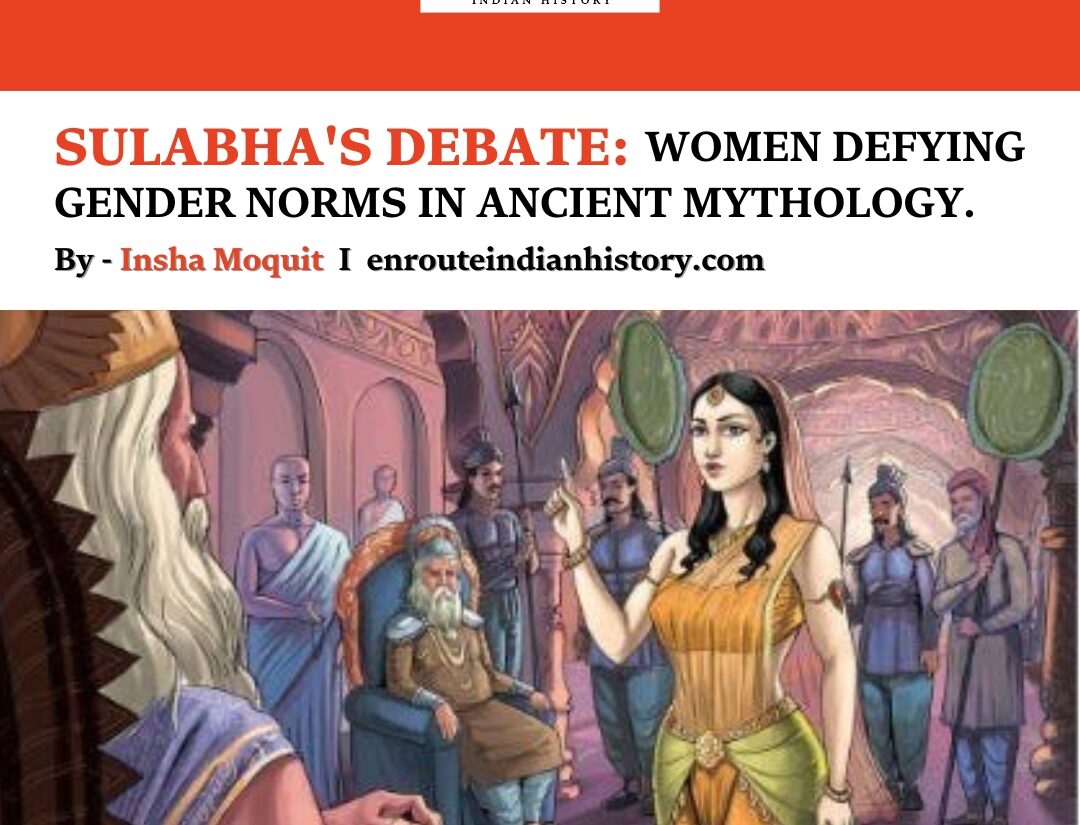

As for Sulabha, who is she? Not many people immediately know the name. In the ancient epic Mahabharata, she is a single, learned renunciant lady who defeats the philosopher-king Janaka in a debate in front of distinguished Brahman scholars. Sulabha rationally proves in this debate that there are no fundamental differences between men and women. She also gives an example of how a woman might get emancipation using the same methods as a man. The Saulabha Shakha of the Rigveda Samhita is attributed to her. In the Kaushtiki Brahmana, she is recognized as a teacher who deserves salutations.

(Art of Yogini, source: Wikicommons )

CONTEXT OF THE DEBATE

As its name suggests, the Shanti Parva is about peace in every dimension. More precisely, this extended passage in the Mahabharata involves a discussion between King Yudhishthira, the oldest of the five Pandava brothers, and his great-uncle Bhishma. The dialogue takes place following the Pandavas’ victory in the war.

Yudhishthira poses a question about preventing old age and death at one point in this section. Bhishma informs him that King Janaka had posed this issue to his instructor, the Rishi (ascetic) Panchashikha, who had replied that death and old age were inevitable. Like life itself, all human relationships are fleeting. To break free from the cycle of rebirth and thereby avoid death, one must also escape birth. Then, Yudhishthira, who is also a spouse, father, and king, queries whether it is possible to break free from the cycle of reincarnation without giving up on the traditional way of life.

Bhishma responds by telling Sulabha and Janaka’s tale. According to ancient Hindu writings, King Janaka is the model of the philosopher king—a guru and ruler who is absolutely intelligent. According to Bhishma, while traveling the earth, Sulabha, a female dicant and yogini, learns from numerous ascetics that Janaka practices the religion of emancipation and makes the decision to visit him. She transforms into a stunning young woman with yoga abilities and presents herself to Janaka as a mendicant. Her beautiful appearance fills the king with astonishment. He greets her as an esteemed visitor, places her in a first-rate seat, and provides her with delicious food and water to wash her feet. After that, he asks questions about her identity, ancestry, and current whereabouts.

Bhishma goes on, “With doubts about Janaka’s ability to achieve emancipation,… Sulabha, endued [endowed] with Yoga-power, entered the king’s understanding by her own understanding.” Her action is referred to as “sanchodayishyanti,” which suggests that she is questioning or examining him within using her yoga powers rather than outwardly. Janaka responds to this scrutiny with animosity. As both a king and a sage, Janaka embodies the highest form of male prowess. Janaka finds it particularly annoying that a woman is testing him on an equal footing because he is not used to being put to the test or challenged in this manner.

(Source: Google Photos)

JANAKA’S STEREOTYPICAL SCRUTINY

In spite of his status as a king and his marital status, Janaka asserts that he is free from all attachments and has acquired knowledge of the Atman, or the understanding that one’s Atman is one with reality. Even if he is still alive, he is free. He then audaciously asserts that he is better than all ascetics who have given up on the world. In this context, his contention is that, on the one hand, an ascetic’s renunciation of the world might only be apparent and not genuine, and, on the other hand, a king’s attachment to and enjoyment of the world might also only be apparent and not genuine. And with that, he makes a determined attempt to prove that Sulabha is not a true renunciant.

He informs Sulabha at the outset of their dispute that her behavior is inconsistent with an ascetic lifestyle. He is skeptical that she has dulled her senses because she is young, attractive, and delicate. This suggests that a young, attractive lady is powerless to resist her cravings for sensuous, sexual pleasure. He continues by saying that it is wicked for her to have delved inside him through yoga powers. He continues by speculating that she may have committed all these immoral behaviors due to “ignorance or perverted intelligence,” but regardless, she has exposed herself as an evil woman by attempting to assert her dominance over males. He wonders if she works as a spy for a competing ruler. This conjecture suggests that he cannot imagine a female agent acting on her own initiative and believes she is only a tool serving a male leader.

SULABHA’S RESPONSE

To start, Sulabha answers the king’s questions about her identity, ancestry, and persona. “The existences of all creatures exist commingled when brought together, just as lac and wood, as grains of dust and drops of water, exist,” is her response. This is a statement of the philosophical stance that all bodies and beings share the same fundamental elements, and all entities, whether male or female, are permeated by the same consciousness. As a result, if Janaka were truly knowledgeable, he wouldn’t ask for her identity because he would know that she and he are fundamentally the same.

This argument shows that differences in sex are not always necessary. To think of it as necessary is to be misguided. The king is not as emancipated as he professes to be, as evidenced by his emphasis on gender differences. If he were, he wouldn’t distinguish himself from other people.

Sulabha asserts that although Janaka’s body is different from hers, her spirit (Atman) is the same as his or any other person’s spirit. When Janaka regarded the union of selves as a tangible union, he confounded body with self/spirit. A knowledgeable individual understands that the self is not really connected to either their own body or the bodies of others. She further informs Janaka that no husband could be found who is suitable for her and that she is a member of a royal family like him. She travels the world by herself while engaging in asceticism.

(Female Ascetic in Hindu Mythology, Source: Wikicommons)

RELEVANCE OF SULABHA’S DEBATE IN THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD

The above-mentioned discussion of Sulabha’s debate with King Janaka demonstrates her immense wisdom and questions patriarchal presumptions about women’s capacities and social duties. In a society where women’s rights and individuality are still questioned, Sulabha’s demand on being acknowledged as an intellectual equal to men is extremely important.

Sulabha’s account highlights the ongoing fight for women’s equality in the context of today’s gender discussions, which center on topics like body autonomy, gender wage disparities, social security, and employment discrimination, among many others. Her defiance of restrictions based on gender is a reflection of the continuous struggle against the structural obstacles that women encounter in contemporary society. Sulabha’s intellectual sparring match with Janaka, in which she challenges male-dominated power systems and declares her independence, which is reminiscent of our current struggles against social standards that limit women’s potential and freedom.

By going back and reconsidering Sulabha’s debate, we can draw strength and validity from it for the current gender debates, keeping in mind that achieving equality is a lifelong process with deep historical roots and is necessary for an equitable and just society.

REFERENCES

Altekar, Anant Sadashiv. The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization. Motilal Banarsidass, 1956.

Bader, Clarisse. Women in Ancient India. 1925. Reprint, Routledge, 2000.

Bhattacharji, Sukumari. Women and Society in Ancient India. Basumati Corporation Ltd., 1994.

Bhavalkar, Vanamala. Woman in the Mahabharata. Sharada Publishing House, 1999.

Kinsley, David. Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press, 1986.

Kishwar, Madhu. “From Manusmriti to Madhusmriti: Flagellating a Mythical Enemy.” Manushi, no. 117, 2000, pp. 3-8.

Shah, Shalini. The Making of Womanhood: Gender Relations in the Mahabharata. Manohar Publications, 1995.

Vanita, Ruth. “The Self Is Not Gendered: Sulabha’s Debate with King Janaka.” NWSA Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, July 2003, pp. 76–93. https://doi.org/10.2979/nws.2003.15.2.76.

Vidyalankar, Sumedha. Mahabharata Mein Shanti Parva Ka Alochnatmak Adhyayan (A Critical Study of Shanti Parva in Mahabharata). Eastern Book Linkers, 1984