Tales of the Thakurbari: Untold stories of the women of the Jorasanko Manor

- Anoushka Jain

- November 23, 2021

Article by EIH Researcher and Writer

Akansha Sengupta

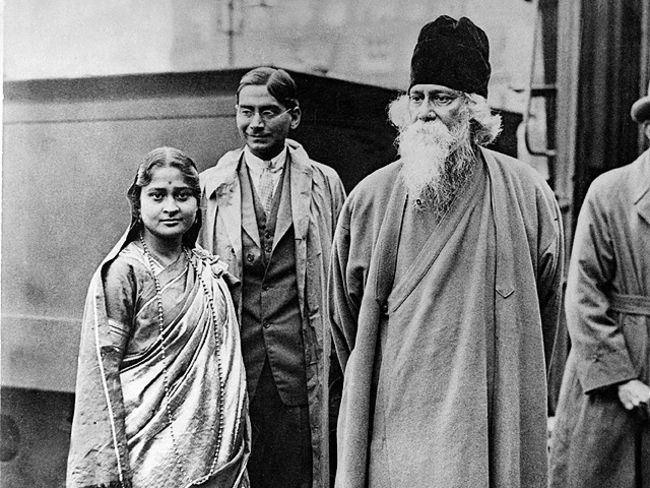

Tagore, with an eye for detail, has always captured and highlighted the turbulent lives of women in colonial India. His expansive body of work often explored women at the mercy of men, but Tagore’s heroines were valiant women who challenged tradition and moved beyond established norms. His short story, ‘Laboratary’, written a few months before his death calls upon this ‘new woman’, with an agency that is not restricted. This new woman has an identity, which is not confined to just being a dutiful wife or a loving mother. Her narrative is not associated with the men in her life, rather she writes her own stories. Tagore challenged Bengal’s rabid obsession with widows and controlling their lives after their husbands’ passing. Binodini, from Choker Bali, showcases resistance when asked to mold herself into a widow. Back in the day, a woman’s life ended with her husband’s. In parts of the country, this practice was called Sati, but in Bengal, widows were considered lesser beings, singled out of public life, and ostracized. With their shaved heads and plain white clothing, their lives were dull. They were pushed into the periphery of society, seen as beings devoid of needs or desires. Emotional and physical intimacy, companionship were things of the past for a lot of widows. Moreover, thinking of remarrying was as vile as treason. Tagore challenged this phenomenon far too many times.

However, while Tagore was not never too comfortable with the strident assertion of women’s rights and an institutional change that would lead to an equal society, he showed a remarkable understanding of their tumultuous situation. His stories largely represented three facets of women’s lives, the romance between men and women, social oppression and societal hopes that pin down women and the new or modern woman.

When Tagore was writing, the age of consent debate was raging in colonial Bengal. 19th century colonial Bengal was not a time when individual rights as an explicit claim could not be asserted by women. When situating Rabindranath Tagore in a historical context, one would realize that Bengali society was rapidly changing and evolving. The literary extraordinaire spent eight eventful years in colonial Bengal. The advent of Ram Mohan Roy’s Brahmo Samaj was changing the way many Bhadralok Bengali’s viewed society. Tagore’s father, Debandranath Tagore, was an imminent member of the Brahmo Samaj. Meanwhile, there was a revolution in literature, with Indian voices of dissent taking center stage. The Bengali literary scene was dominated by new ideas of romance and love, owing to the influx of Great Britain returnees, who’d already had a taste of British theatre and European romantic literature. Tagore largely stuck to his argument of breaking away from age-old beliefs of child marriage and introducing ideas of modernity in Bengal. He extensively wrote and lamented about child marriage and the burden of a young widow.

But there is always a dichotomy between public and private faces. Did he practice what he preached, behind closed doors? Rabindranath Tagore, a towering vanguard of women’s rights had given into societal patriarchal norms. And the women of the Jorashanko manor would second that. It is important to note that these are real people, not fictitious characters from his stories. Scholar and renowned scholar, Aruna Chakravarty explores this facade in her book titled, Jorasanko. The manor has seen semblance to a lot of rich history and culture, but however, there was inner turmoil brewing within the Thakurbari. The Thakurbari saw unequal marriages not just by age, but huge tussles in caste and class hierarchies. The walls of the manor bear witness to misogyny and imbalanced autonomy. Tagore, despite being a staunch protestor against child marriage, had married his daughters off at the tender age of 10 and 11. “He even accepted to pay dowry for his elder daughter’s wedding”, writes Chakravarti. The Nobel Laureate also funded his son-in-law’s education abroad. Whether his daughter had access to education is still shrouded in mystery. But we cannot call his approach to women’s rights misleading. He was not feigning his support for a more equal society. Societal factors made him buckle down and give in. Perhaps he was not a feminist meant for his times. But his vision is appreciated far and wide. Chakravarti writes that “ the disquiet poet’s sadness and melancholy also came from the fact that his ailing daughter was not getting adequate care from her in-laws’ ‘.

His class relations and contemporaries have often allegedly described this phase in Tagore’s life as a dark streak. Incidentally, the imposing age difference of almost a decade between the married couples invariably prompted the women to bond with the younger brothers-in-law of their same age bracket instead. This seems to be the story of every Bhadralok Bhari or every upper-class home. For instance, the intimate friendship between Balendranath and Mrinalini Devi. Amidst all this chaos, there seems to be a romance brewing between Tagore and his sister-in-law, Kadambari, who is regarded as his muse. Kadambari Devi really helped Tagore reach the zenith of his artistic ability. Kadambari recognized his talent and helped him free the muses trapped within, Kadambari along with Jnanda are considered as the strongest influences in the poet’s life and work.

The hierarchy at the Thakurbari was simple, young girls come to the manor as child brides and leave only when they pass. The Tagore men burst into the Bengali Renaissance, while some of the women stayed cloistered in the kitchens. The Bhadralok’s eloquently engaged in the reform movement, whereas the boudi’s remained welcoming their husbands in their bed chambers. But there were many who broke into rebellion, ridding themselves of the shackles of patriarchy.

We have the queen of Haute fashion in the Tagore pantheon, Jnanandandini Devi. The ever charismatic Jnanandandini Devi entered the illustrious household at the young age of 7 and along with her, she brought a revolution. Married to Satyendranath Tagore, her early years in the family were far from merry. Perturbed by the stringent “Abrodh or Purdah” system that all Tagore women had to follow, she started a new life with her husband, as the couple abandoned the Jorasanko house and moved to Bombay. Bombay really molded Jananda into a force to be reckoned with. Like the Tagore’s, even she had an artistic failure. She’d often assist Rabindranath Tagore in writing plays, she’d lend an ear to his creative ventures. She became the first woman to star in a play which was a remarkable feat for a woman of that time. The play titled, ‘Raja O Rani’, invited a lot of criticism from people condemning her act of defiance. But it was instrumental in opening up doors for women wanting to enter the performing arts. Jnanada paved the way for many women wanting to write, she started writing for Bengali chronicles and magazines. Nationalism and dissent against the British were an expansive theme in her work. In her new home, she freely mingled with Europeans and got more insight into the world outside the Thakurbari. She attended luncheons and garden parties, threw tea parties, and learned the art of entertaining.

She was the mind behind the Bramhika Sari. In 19th century Bengal, women literally draped themselves with the saree, their faces were covered with a ghumta or ghoongat coming up to their chests. This attire was highly uncomfortable and restricted their movement. Moreover, the cloth was very thin and they did not have anything to protect them from cold winter nights. Inspired by the Parsis, Jnananda devised her own way of wearing a saree. She elegantly made pleats that were tucked in the waist, while the end of the drape (pallu) was thrown over the left shoulder. The look complimented her greatly and made movement much easier. On her return to Calcutta, women were awe-struck with her innovative way of styling her saree. Soon she was teaching other women. Women from the Brahmo Samaj only wore the saree in the Bramhika style. She popularised the modern style of draping the saree, which is not just used in Bengal, but across India. In 1877 she set sail for England, heavily pregnant and accompanied by her three children. Back then, a woman crossing the threshold of their marital home was unheard of, let alone crossing the seas. Jnanadanini Devi would soon begin to write her own history as Bengal’s first modern woman, who inspired and touched lives.

Another flamboyant woman from the Tagore clan was Swarnakumari Devi. She was one of the first Bengali women writers to gain prominence. Though she is treated like a forgotten character in Bengali literary history. She has almost faded from the literary memory of India, while her brother Rabindranath Tagore rose to fame. The 5th July 1932 issue of the Amrita Bazar Patrika, remembers Swarnakumari as, “one of the most outstanding Bengali women of the age who did her best for the amelioration of the condition of womanhood in Bengal”. A trailblazer in philanthropic work, Swarnakumari Devi opened the Sakhi Samiti, an organization that provided free education for widows and orphaned children. It also provided shelter to widows. She actively resisted the British Raj and English hegemony. She dreamt of a free India where equality prevailed. Perhaps her biggest battles is her erasure from history and the way she was overshadowed by her brother. Many of her works remain untranslated, moreover, there has barely been an attempt to reconstruct and study her life and work by modern historians. More than remarriage she focused on women’s liberation and emancipation. She believed that women needed financial freedom and education to free themselves from a cycle of misogyny and patriarchy. Her work gave creative freedom to many aspiring women writers who were caged by their circumstances. She took part in the Indian freedom struggle and the Swadeshi movement and contributed to social reform in a largely repressive Bengal.

Miralini Devi, Rabindranath’s wife is also not to be taken lightly. While her husband was one of the greatest men of his time with an even brighter mind and zeal for writing, how could she be left behind? Hailing from a simple family, education was not heard of in her part of the world. She spent 19 years as his wife. During these 19 years, her narrative was only tied to him. But she strived to make an identity of her own. She started school shortly after her marriage to Tagore and was deeply fascinated with author Mark Twain. She is credited with translating the Katha Upanishad in Bengali. She acted alongside her sister-in-law in the play ‘Raja O Rani’. It is said that she sold off almost all her jewelry to fund Tagore’s school at Shantiniketan.

Therefore, we see a few exceptions, the manor was not always mired with scandal. Some women stepped out of their husband’s shadows to assert their identities, while we have some abandoning their husbands and starting new lives, promptly thwarting established norms and gender roles. These women are more or less shrouded in history, but accounts allude to the very topsy-turvy and eventful life they led. Thakurbari saw hopes, fears, independence, and assertion.

Bibliography:

- https://www.getbengal.com/details/why-rabindranath-tagore-never-dedicated-any-book-to-his-mother

- “New Woman”, in Tagore’s short stories. (The Asiatic, Volume 4)

- Jorasanko- Aruna Chakravarty