Sacred Spaces and the Emergence of Temples

“Certain areas on earth are more sacred than others, some on account of their situation, and others because of their sparkling waters, and others because of the association or habitation of saintly people.”

(Mahābhārata Anuśāsana Parv

This verse seems to communicate that sacredness is not inherent but contextual and could be manifested through associations with the divine, spiritual figures, or unique natural features. Thus, the idea of sacredness in Hindu tradition is both fluid and complex, not constrained to objects or individuals but also encompassing physical spaces like temples.

(Modern replica of utensils and sacrificial altar in the Vedic religion, credits – By Arayilpdas at Malayalam Wikipedia)

Contrary to the popular assumption that temples have always been central to Hindu practice, historians have reported that they only became significant relatively late in its history. Hindu traditions existed for over a thousand years before the construction of temples became common. Vedic rituals, the foundation of early Hindu practices, were typically performed in temporary structures, while domestic rites described in the Grihya Sutras took place within homes. Terms for temples, such as devalaya, devayatana, and devagriha, begin to appear in literature from the 3rd century BCE onwards, signaling a shift. According to the scholar PV Kane, it is striking that none of the principal Grihya or Dharma-sutras outlines procedures for consecrating temple images, further illustrating the marginal role temples played in early Hinduism. In this period, temples were often located far from villages and towns, serving only as temporary shelters for ascetics. For these spiritual wanderers, the temple had little to no significance in their religious life. In essence, while temples eventually became prominent in Hindu practice, their rise to importance was gradual and fraught with complexities, shaped by social, religious, and cultural shifts over centuries.

The Transformation of Religious Spaces

The evolution of theistic traditions in the Indian subcontinent is often viewed as an extension of the Vedic religion, which was primarily centered around sacrifices and rituals. Unlike the fixed religious sites that emerged later, Vedic practices were largely portable and not tied to specific geographic locations. The concept of shrines, however, marks a significant shift in religious traditions, introducing the idea of sacred spaces defined by physical locales often taking the shape of large temples. This transitional phase between the sacrificial Vedic religion and the devotional practices of Purāṇic worship also features the development of ‘tīrthas’ (sacred pilgrimage sites). D. Desai asserts that during the fifth century CE, many feudal centers saw the construction of temples from durable materials like stone for the first time. This shift was driven by the rising significance of Bhakti and the newly established Smārta-Purāṇic religion, which aligned with the evolving social structure of the period.

Before the 5th century, most Brahmanical shrines were temporary, evidenced by depictions of rituals being performed in simple shelters at places like Bharhut and Sanchi. However, as Indian deities began to take anthropomorphic forms, the need for permanent structures became evident. Over time, clearings in forests or reed huts evolved into wooden sanctuaries, eventually leading to stone temples during the Gupta period. The garbha-griha (sanctum sanctorum) became the nucleus of these temples, with the architectural forms of this period laying the foundation for grander temple designs in subsequent centuries. While the temples of the Gupta period were modest in scale compared to later medieval constructions, they represented a significant shift in the nature of worship and religious representation.

Gupta Period and the Role of Royal Patronage

The Gupta period marks a pivotal phase of transformation in Hindu religious and cultural practices. Historian Michael Willis emphasizes the changes during this era, noting a shift from Vedic traditions, which were characterized by non-monumental rituals, to the establishment of grand temples, shrines, and sculptures. This monumental religious architecture was not only a reflection of the king’s aspiration to become a universal monarch but also of a broader cultural change. Queens, ministers, and subordinate kings contributed to this trend, highlighting the widespread patronage that underpinned temple-building activities.

The large-scale patronage practiced by the Gupta rulers and their court officials (amātyas), along with regional elites (sāmantas), played a central role in the development of classical forms of Indian religions. The royal sponsorship of temples and sacred art was part of a deliberate political strategy, through which rulers sought to establish and legitimize a religiously sanctified social order, known as dharma. This religious-political alliance bolstered the ruler’s authority, as kings were perceived to rule by divine grace. As a result, religious monuments, many of which survive today, proliferated across North India, showcasing the stability and grandeur of their reign—so much so that it is often referred to as the ‘Golden Age’ or the ‘Classical Age.

Gupta Architecture and Religious Symbolism

The Gupta period marked the rise of a distinctive architectural style, termed “proto-Nāgara,” which originated in the Gangetic basin and central India. This early form of temple architecture eventually laid the foundation for the Nāgara style, which became a mainstream feature in Indian temple design. Beginning with the simple āmalaka shrine, temple structures grew increasingly complex during the fifth and sixth centuries, as the superstructures expanded and became more intricate. A notable element of this architectural evolution was the inclusion of river goddesses like Ganga and Yamuna, who flanked the doorways leading to the sanctum.

(Ganga and Yamuna, Gupta period, 5th Century CE, National Museum Delhi, image credits @devasakha on x.com )

While the Guptas are frequently associated with the rise of Vaisnavism, their reign was also marked by religious tolerance mixed with political strategies. Temples were erected across the empire, particularly in newly conquered regions, serving to solidify the dynasty’s control. The uniformity in temple design across the empire reflected the Guptas’ desire to foster unity and promote a shared religious identity, which contributed to the stability of their reign. By supporting the construction of temples dedicated to a personal deity accessible through devotion, the Guptas sought to create a unified religious movement that aligned with Brahmanical practices. This religious integration not only helped consolidate the empire but also bridged the gap between local traditions and the overarching Brahmanical framework.

A Glimpse into Gupta Temples

To understand the architectural advancements and religious fervor of the Gupta period, it is essential to explore some of the key temples constructed under their patronage. Let’s take a look at some of the prominent Gupta temples that stand as enduring testaments to this era.

(Udaigiri Cave temple , image via Newsbharati.com)

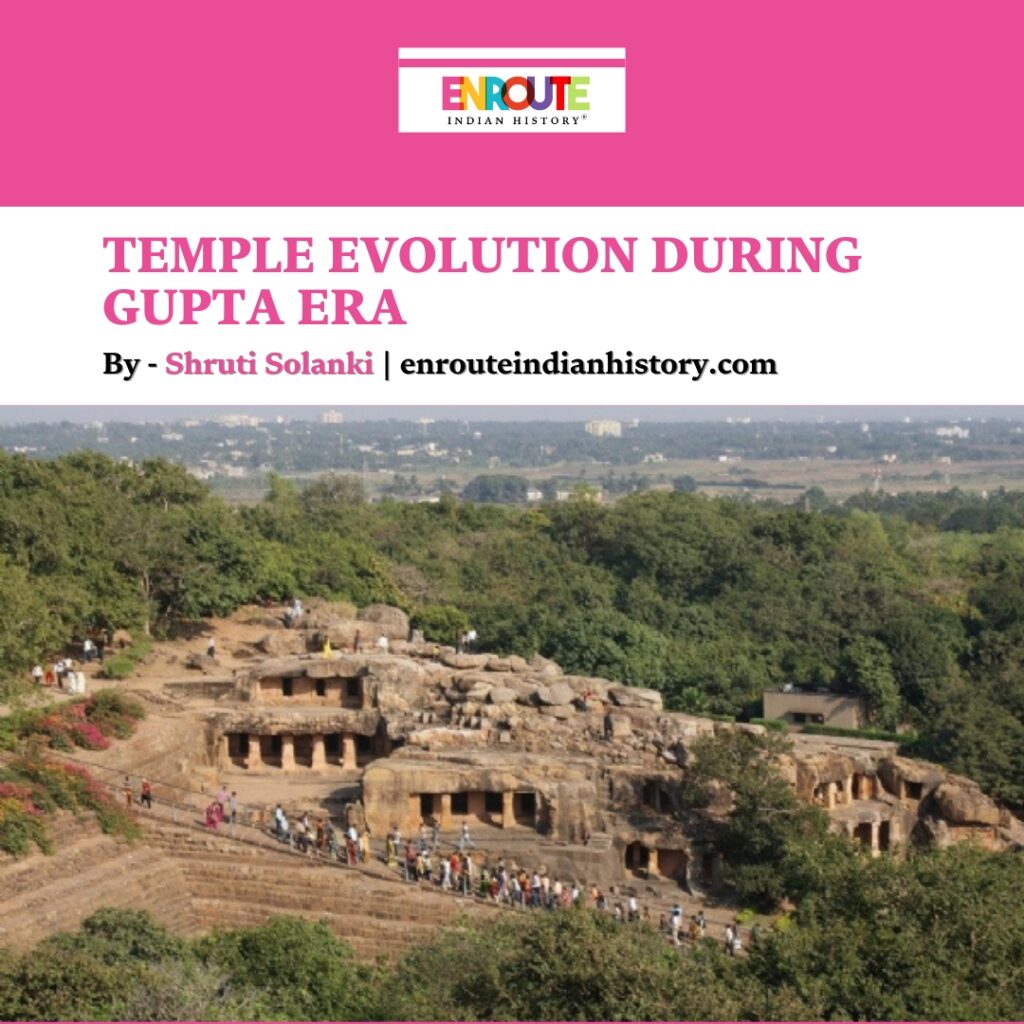

Udaigiri Temple:

It is home to what is considered as one of the earliest Brahmanical sanctum that survived. This temple, often referred to as the ‘False Cave’ or ‘Chandragupta Cave,’ signifies the early phase of Gupta temple architecture. Its simple, rock-cut structure points to the initial stages of temple development before the emergence of more elaborate designs. Despite its humble appearance, Udaigiri holds immense significance as a pioneering Brahmanical temple.

Sanchi Temple No. 17:

Although Buddhist in nature, is another important example of Gupta architecture. Dated between 400-425 CE, this structure is considered one of the oldest standing temples in India. Though its main object of worship remains uncertain, it is emblematic of the early Gupta style. The lack of an inscription further adds to the mystery surrounding its origins, yet it remains a cornerstone of early temple architecture.

Temple of Kankali Devi at Tigawa:

According to art historian George Michell, Tigawa along Sanchi are among the few free-standing temples from the Gupta era that have been fully preserved. The temple exemplifies the formative stages of Hindu sacred architecture, with its simple design reflecting the transition from Vedic altars to more permanent structures dedicated to personal gods.

(Tigawa temple site , image via wikimedia commons)

The Vishnu Temple at Deogarh

Also known as the Dasavatara Temple, it is renowned as the earliest example of a temple with a Sikhara, a towering superstructure that would later become a hallmark of Hindu temple architecture. This temple marks a significant departure from earlier Gupta styles, representing a shift towards more monumental temple forms. The ornate sculptures and the depiction of Vishnu’s ten avatars on its walls highlight the growing importance of bhakti and Puranic worship during the Gupta era.

![]()

(Vishnu temple at Deograh)

Conclusion

From the humble cave sanctuaries of Udaigiri to the towering Sikhara of Deogarh, these structures not only embody religious significance but also highlight the broader socio-political currents of the time. The strategic placement and uniform style of temples throughout the empire reinforced the political authority of the Guptas, showcasing the interdependence between religion and governance. These temples, evolving in complexity and grandeur, mirrored the empire’s expansion. They functioned as more than places of worship— as Michael Meister notes, temples acted as ritual instruments, weaving societies into a complex social fabric that persisted through time. This fusion of religious and imperial authority solidified the Gupta dynasty’s influence, with temple building becoming a hallmark of their reign.

Rather than marking a sharp divide between Vedic and Puranic traditions, these structures symbolize a reconfiguration of religious practice. While Vedic sacrifices continued, they were integrated into the emerging temple culture, where pūjā became the dominant form of ritual. The association of sacredness with physical spaces, as reflected in texts like the Mahābhārata, underscored the evolving significance of temples as both religious and political symbols. Over time, temples became central to Hindu worship, reflecting not only spiritual aspirations but also the economic and political strategies of royal patrons.

References –

Mishra, Susan Verma, and Himanshu Prabha Ray. The archaeology of sacred spaces: The temple in Western India, 2nd century BCE–8th century CE. Routledge India, 2016.

McKnight, Michael John. The Gupta Temple Movement: A Study of the Political Aspects of the Early Hindu Temple. Diss. 1973.

Ślączka, A. A. “Temple Consecration Rituals in Ancient India: Text and Archaeology.” Research Archive, 4 Oct. 2006, https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4581.

Bakker, Hans. “Royal Patronage and Religious Tolerance The Formative Period of Gupta–Vākāṭaka Culture.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 20.4 (2010): 461-475.

Olivelle, Patrick. “When Did Large Hindu Temples Come into Being? Not Before 500 AD.” The Print, 17 Jan. 2024,https://theprint.com/.

Ray, Himanshu Prabha. “The shrine in early Hinduism: The changing sacred landscape.” The Journal of Hindu Studies 2.1 (2009): 76-96.