India’s rich cultural legacy is reflected in the way sports are woven into the fabric of the country. Since ancient times, many areas have created distinctive sports traditions that are frequently connected to regional values and customs. These sports promote cultural expression and community building in addition to being physical exercises like Manipur’s Thang-Ta.

The country also has an abundance of martial arts traditions to match its varied landscapes. Every area has a distinct style that reflects its cultural background. These fighting styles, which range from the fluid movements of Kerala’s Kalaripayattu to Punjab’s Gatka stick-fighting technique, convey tales of conflict, self-preservation, and artistic expression.

However, hidden away in the stunning highlands of the Northeast is an untapped treasure. Manipur-born Thang-Ta is a colorful addition to this already vibrant tapestry. Amidst the mist-covered valleys and cloud-piercing peaks of Arunachal Pradesh, a place of calm beauty, there are warriors with spears and swords, and they move with the might and grace of Himalayan eagles in the air.

There are many myths and traditions about Thang Ta’s origins. When there was complete nothingness at the beginning of time, Atiya Guru Sidaba, the Supreme Creator, produced Asiba, his son, and asked him to construct the universe while sitting on his own breath. Confused about how to create anything out of nothing, he asked his father for advice. The Creator then parted his lips and let his son peer within, whereupon he beheld the entirety of the universe inert and awaiting manifestation.

In addition, he was told to construct a dance called Thengou, modeling his motions on the ground—the same arrangement of nerves and veins that supported the cosmos at the time of its creation—by using his father’s nerve and vein configuration. Thengou, a dance composed of a fusion of martial art motions, was thus the first act of the universe which eventually evolved into Thang Ta.

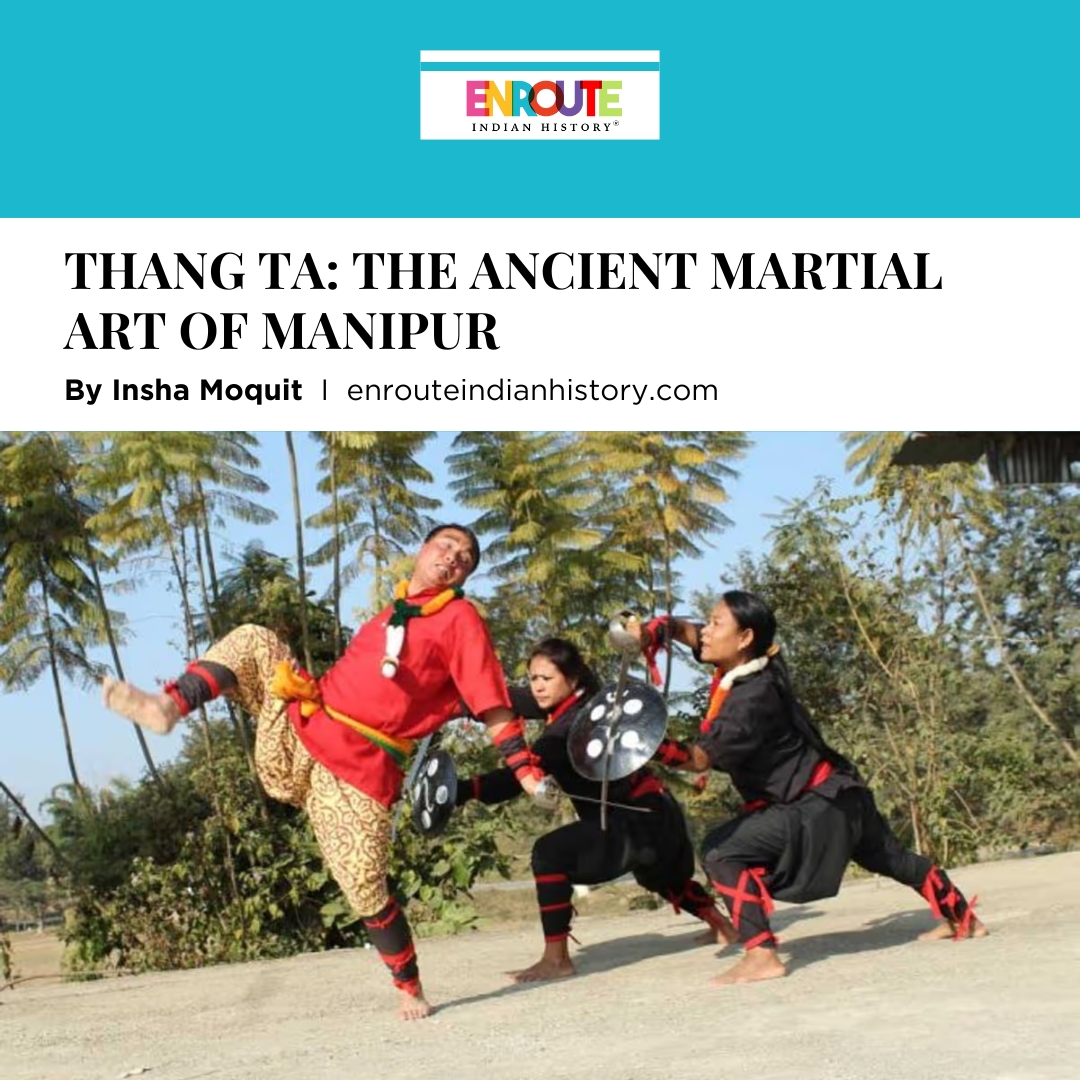

The Art of Sword And Spear

(The sword and the spear of Thang Ta, source: wikicommons)

Thang Ta, or “The Art of the Sword and Spear,” is part of the great heroic tradition of Manipur and integrates various external weapons, such as the sword, spear, dagger, etc., with the internal practice of physical control through soft movements coordinated with the rhythms of breathing. The proper name for Thang-Ta is HUYEN LALLONG, translates as “knowledge of war art” (Huyel being the word for war and Langllon for knowledge of art). As the name suggests, Huyen Lallong is more than just the training of fighting skills; it is an intricate system of physical culture that involves breathing techniques, meditations, and rituals.

Even though the sword and spear forms are made of material skills, some of them are wholly ritualistic. They are to be conducted exclusively at exceptional events or under special circumstances. For example, there is a spear form that is performed at funerals. The spear dance performed ceremoniously on a mountaintop by King Bhagyachandra (1759–1798) CE during his banishment owing to the Burmese invasion in 1762 CE is arguably the most well-known form. Manipuris think that the rite had a key role in forcing the Burmese people to leave Manipur.

The “sword” is Thang-Ta’s core. Sword drills abound, with literally hundreds of variations available to practice fundamental movements and stepping patterns. While many are practiced in pairs, some can be done alone at first. The Thang-Ta spear forms are more intricate and require observation to fully understand. “Many are the warnings given by the old teachers to their students who, they say, may seriously injure their limbs by incorrectly stepping according to the design –Pakhangba, a coiled serpent motif” ( Hall and Lightfoot)

Soul of the Sword: Practicing Thang-Ta

The discipline is descended from the physiographic and cultural milieu of the Manipur plains and hills, and the martial system makes far more extensive use of the body to reach out into the opponent’s space. sword and spear are both part of the weapons used by the dominant ethnic group in the plains, the Meitei. While the figure of eight is frequently employed to cover all vulnerable regions of the body, the sword is most effectively used to defend the body from attacks from all directions. The self as target is dynamic, constantly shifting positions, and the Manipuris frequently employ movement rather than stillness when getting ready to confront the opponent.

(The weapon training of Thang Ta , Source: Google Photos)

A standard Thang-Ta class includes mastery of the Thang (sword), Ta (spear), and other conventional weapons included in weapon training. Developing grappling and self-defense skills is part of unarmed combat.

Strength, flexibility, and endurance are all built through physical conditioning. Knowledge of the fundamental ideals and tenets of the Thang-Ta Manipuri martial art is included in philosophy.

The cultural and customary uses of daily living inform the movement patterns of the various portions of the Manipuri martial body. A number of stances, gestures, and extra-daily postures are combined into codes that expand on the natural repertoire.

Physical Characteristics in Customary Usage and Ritual Practice

1.Khurumba (the bow) – where the forward/downward flexion of the relaxed spine is used.

2.Tha Leiba -Rotation and tilts of the pelvic joint at different angles while supporting the torso in regular curvilinear uses are most common. The half turn of the chest is also common.

- Thong khong (bridge support) – The squat is also a familiar use of the lowering of the upper extremities nearer to the ground, where the two legs in deep bent position support the whole body, thereby proximally utilizing the use of the upper extremities at ground level. Men use three squat positions in descending order to enable a firmer hold of the body in pro-gravitational positions.

- Wai teiba – a daily ritual of cleaning the floor by women. Women use a different flexible squat system with the bent knees opened out to enable forward flexion of the torso or spine. The hand uses the washcloth with more space at her command while rubbing the floor. The entire system of body use is rich and varied, and the wrists could be most appropriately exploited in Khujeng Leibi (wrist circling) to emulate the figure of eight.

Thang (the art of the sword) emphasizes Phidup (coil), lowering of one’s body near to the ground to enable a spring action for expansion and attack.

TA (spear) emphasizes Phanba, an opening out of the body with two forms, Nongphan to stimulate the expanse of the sky, and Leiphal emulating the expanse of the earth at ground level in order to reach out to all directions of space. The spear uses about 75% of the lower extremities in motion, while the wielding of the sword normally requires 75% exercise of the upper extremities.

(Women practicing Thang Ta, Source: Thangta.com )

The practice of Thang Ta requires a considerable amount of self-control from those who follow it. Some even fear that some vices could compromise the abilities that have been developed after years of training, devotion, and meditation. Certain food varieties are also prohibited. The Scriptures include several fundamental moral precepts, one of which is that an adversary who is fleeing, hiding from danger, crying out in fear, or who has requested protection should not be harmed, not even during a conflict. Any breach of this is regarded as a serious transgression. For a warrior, there are laws that govern every aspect of his life. Breathing, eating, and sleeping patterns are all in check.

Training in martial arts is more physically demanding at first, but it becomes increasingly spiritual as one progresses. The student is eventually given access to the yantra, mantra, and tantra secrets. The protection of the land, people, monarch, and the weak should be the warrior’s primary and sole responsibility. There is no finer representation of this spirit of selflessness than the outfit he dons in combat. It also contains a sacred robe that is typically worn by the deceased, readying him for the greatest sacrifice of all. In reality, though, each of these branches is dependent on the others and cannot exist in a vacuum.

Thang-Ta: Where Dance Meets Martial Mastery

The Thang-Ta Manipuri martial art is a beautiful dance of human potential, not just brute force. Watch a Thang-Ta performance, and you’ll see the mesmerizing flow of warriors wielding their weapons; the clash of steel is a symphony of coordinated movements and rhythmic breathing; these performances, called “Choloms,” harken back to a time when martial art was used as both a training ground and an entertainment medium. Villagers would gather to watch the warriors’ prowess, their movements were a testament to courage and skill.

(Khongjon, The cultural Dance in Thang Ta Performances, source: wikicommons)

The ritualistic postures and dances used in Thang Ta performances, or “khongjon,” have deep symbolic meaning. Many times, these staged scenes are part of the ‘Lai Haraoba’ festival, which honors the Manipuri gods. The beautiful, dance-like routines called ‘thang-ta jagoi’ combine sword proficiency with flowing moves that are evocative of Ras Lila and other Manipuri classical dance traditions.

The Thang Ta demonstrations are enhanced by the rhythmic quality of traditional instruments like the pena (string instrument) and pung (drum). The performers, dressed in traditional dhoti and turban, perform intricate maneuvers that tell stories from Manipuri folklore and historical epics like the Khamba Thoibi. Two of the most important performances are the “thang-ta pheisaro” (sword dance) and “ta-khousaro” (spear dance), which reflect the warrior ethos of the Meitei people. These performances not only preserve ancient martial techniques but also function as a living repository of Manipuri cultural values, guaranteeing the continuation of this rich heritage for future generations.

Every thrust of the Ta and every swing of the Thang becomes an extension of your will, demonstrating the Manipuri people’s unshakeable spirit. The warrior’s dance performed here on the training grounds is more than just a display of artistic skill; it is a dialogue between the mind and body that may ultimately determine the future of your town. The heart of Thang-Ta Manipuri martial art lies in this combination of artistic expression and lethal expertise; it is a tradition that has been passed down through the generations and is just waiting to be found.

A Legacy That Lives On: Manipuri Martial Art in the Modern World

(Performative Thang Ta in Manipur’s Lai Haroba Festival, source: Google Photos )

After being outlawed during the colonial raj, thang ta evolved into an expressive art form while maintaining its combative nature in the covert home schools of individual teachers or gurus (1891–1947). It endured until Manipur’s 1949 accession to the Indian Union, and since 1976, it has been exhibited in international festivals and performance spaces.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of awareness and dedicated practice on the part of the current generation, the internal system of meditation techniques and its fundamentally spiritual nature are in danger of disappearing. Practitioners of contemporary theater are becoming more conscious of how to use their body’s resources creatively and for fundamental energy purposes, which will improve the artist’s performance energy.

Nowadays, Thang-Ta is virtually unknown outside of Manipur. The art is not well known in India, despite the 1994 airing of a documentary on Indian television. “Unfortunately, opportunities for Westerners to study Thang-Ta are very limited. Travel to and from the region is restricted; few, if any, people outside of Manipur are able to study the art because of the Indian Government’s entry restriction. To our knowledge, Khilton Nongmaithem is the only Manipuri teaching Thang-Ta outside of Manipur.”

Even so, Thang-Ta embodies the spirit of the Northeast—a fierce determination entwined with a deep respect for tradition—and, just as discovering Manipur’s hidden waterfalls and ancient monasteries reveals breathtaking wonders, practicing and being dedicated to Thang-Ta unlocks its secrets. Thus, when we think of Indian martial arts, we think of Thang-Ta—a warrior dance that echoes in the heart of the Northeast.

REFERENCES

Green, Thomas A. (2001), Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia. California: ABC CLIO

Hall, Renee Renouf, and Louise Lightfoot. “Dance-Rituals of Manipur, India.” Ethnomusicology, vol. 5, no. 3, Sept. 1961, p. 240. https://doi.org/10.2307/924533.

Indu Devi, Ningthoujam. (2016). Manipuri ThangTa amasung Jagoi.Imphal, India: Ashangba Communications.

Kokngang Singh, L. (2000). A Historical Study of the traditional Manipuri Martial Arts (Thang-Ta).p.26. Ph.D. Thesis, Unpublished. Manipur University.

Meitei, L., & Devi, D. (2020). SWOT Analysis of Thang Ta, Indigenous Sport of Manipur for Strategic Management. International journal for innovative research in multidisciplinary field issn: 2455-0620 Special Issue, Special Issue: 17 July – 2020, 215.

https://themanipurpage.tripod.com/culture/thangta.html

https://www.thang-ta.com/