The Closure of Mughal Mints for a Decade: Akbar and the Story of Alf Coins

- EIH User

- June 19, 2024

Introduction

There has been a sense of perplexity among numismatists and historians studying Mughal coinage regarding the absence of coins of almost all denominations from the major mints of the Mughal empire during the period A.H. 989-99 (AD 1581-82 to 1590-1) and their sudden reappearance in A.H. 1000 (AD 1591-92) in large numbers from the mint-name Urdu Zafar Qarin (Camp associated with Victory), with only “alf” (meaning 1000 in Persian) inscribed on them, without any date.

This absence and reappearance have been noted in the museum catalogues of the Mughal coins. Across all available museum catalogues on the Mughal coins, specimens of the coins for the period between 989 hijri to 999 hijri were absent from all the mints, except for the Ahmedabad mint, which continued to produce silver coins, and the copper mints of Ajmer, Narnol, and Dagaon. Notably, for the year 1000 hijri, the number of silver and gold coins in these catalogues was also remarkable.

Mughal coins traditionally feature the name of the mint and the year of minting, providing valuable information for numismatists and historians. This helps numismatics and historians in categorising and cataloguing the coins. Scholars usually use these museum catalogues of coins for their study. The usual method that is used is the statistical analysis of these catalogues and then based on these small sample coins, scholars draw inferences about the circulation of money at a macro level. In this method, the nature of the sample dictates the nature of the results obtained (Deyell 393).

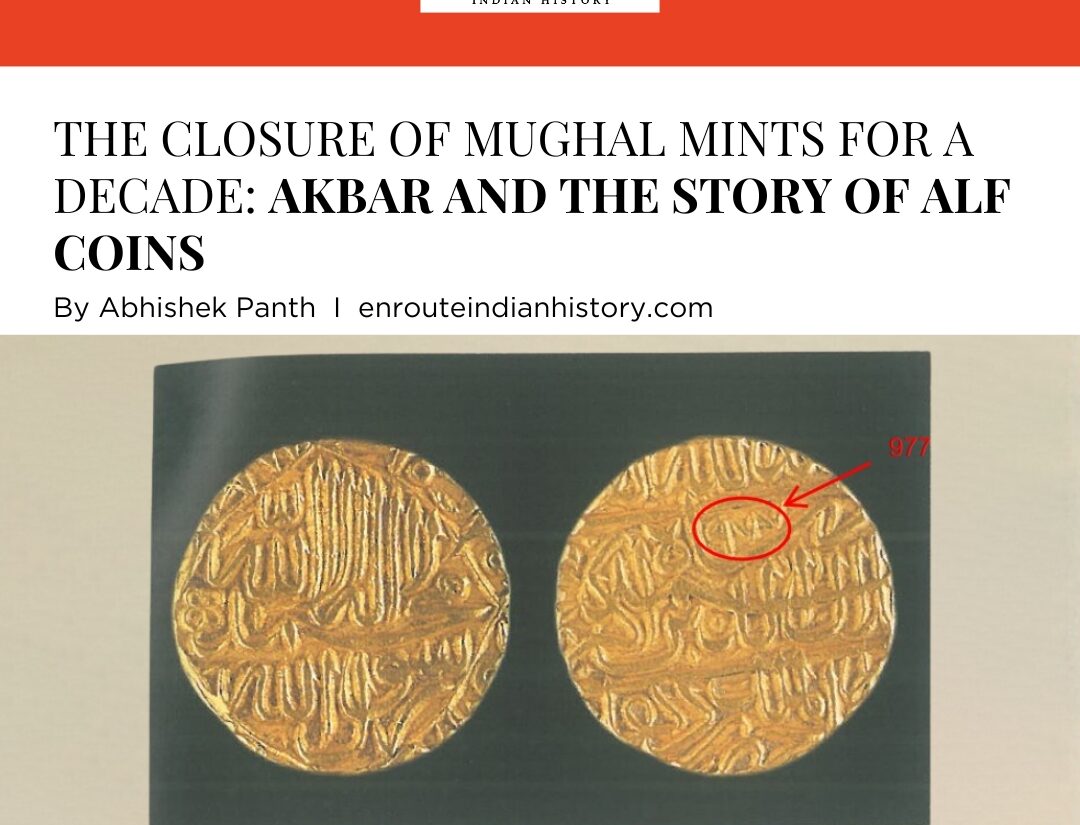

Source: Najaf Haider, “The Monarch and the Millennium”

Another method involves analysing the hoards recovered from archaeological excavations. A hoard refers to a collection of coins that were deliberately hidden or lost as a single unit and subsequently discovered, usually by chance. Hoards represent a deposition of coins that were not retrieved by their original owners due to various reasons such as death or forgetfulness, and have since come into our possession through intentional means or by chance. Analysing hoards provides historians with insight into the mindset of people from the past, shedding light on their coin preferences, currency circulation, and other related aspects.

While examining museum catalogues and coin hoards of the Mughal era, scholars have observed a sudden absence of coins of all denominations from all major Mughal mints during the above mentioned period. This absence of coins is particularly noteworthy, as Mughal coins began disappearing from A.H. 990 (AD 1581-82), shortly after the reorganisation of Mughal mints in A.H. 985 (AD 1577-78). This raises the question of why such a sudden gap in coin production occurred, given that the minting administration had recently been restructured to streamline the monetary system of the newly conquered Mughal empire.

Numismatist John S. Deyell has proposed that this unexplained gap and disappearance of Mughal coins may be a consequence of administrative reforms gone awry or a major scandal involving mismanagement or corruption, to such an extent that it was deliberately omitted from official records. (Deyell 35)

The variety of reasons for this numismatic issue is debated among scholars. According to P.L. Gupta mints may have ceased to inscribe their names on the coins they produced, resulting in all of them being uniformly referred to as Urdu Zafar Qarin, possibly due to a reorganisation of the mints. However, this explanation does not account for the absence of years from A.H. 989 to A.H. 999 (Gupta 65-66).

On the other hand, according to Deyell, Mughal mints played a crucial role in reminting previously accumulated or obsolete coins. However, once this reminting process was completed, the mint operations became economically unviable. This, in his view, happened in A.H. 988-9 and this resulted in the ‘simultaneous closing of the mints’. He also points out that the mints that survived, such as Ajmer and Nornol, were not involved in the reminting of old coins (Suri coinage), which further supports his hypothesis (Deyell 34).

The hypothesis,however, faces significant challenges. Initially, it fails to account for the lack of gold coinage, as there were very few gold coins available for reminting from the previous regime or in circulation. Moreover, if mints were closed and not working then why Bayazid Bayat, writer of Tarikh-i Humayun wa Akbar, was appointed superintendent of the Fatehpur Sikri mint in A.H. 993 (AD 1585), a fact we know of as a certainty. (Haider 57-58).

The numismatic mystery was ultimately resolved with the assistance of a passing reference in Abul Qadir Badauni’s Muntakhab-ut Tawarikh. Badauni in his text wrote:

And having thus convinced himself that the thousand years from the prophethood of the apostle, the duration for which Islam (lit. religion) would last, was now over, and nothing prevented him from articulating the desires he so secretly held in his heart; and the space (basāt) became empty of the theologians (‘ulamā) and mystics (mashāikh) who had carried awe and dignity and no need was felt for them, and to institute new regulations- obsolete and corrupt but considered precious by his pernicious beliefs. The first order which was given was that on all coins be written alf (1000) and the Tārīkh-i Alfī be written from the demise (rihalat) of the Prophet. (Badauni 301)

This clears it out that all coins struck from A.H. 990 from the mints bore a single date alf (millennium) and that the idea behind this commissioning of new coins and the Tarikh-i Alfi (History of a Millennium) was a new interpretation of the terminal dates of the Islamic millennium.

The Alf coins differed from other Mughal coins in several ways: the minting date was inscribed in words rather than figures, and a new mint name, “Urdu Zafar Qarin,” replaced the actual mint-names.

Image: Silver alf coins. Source: Najaf Haider, “The Monarch and the Millennium”

The concept of an impending apocalyptic year and the arrival of the Mehdi, a prophesied leader, is deeply rooted in Islamic tradition. It is believed that the Imam Mahdi will emerge before the Day of Judgement and establish justice for a period. Although the length of this period isn’t specified, however, according to many Islamic theologies, this period will occur after a thousand (yak hazar) years following the establishment of Islam. Akbar for a brief period was convinced that this epoch was unfolding during his reign and sought to present himself as the Mehdi. Badauni referenced this notion in the aforementioned passage.

Consequently, Akbar marked the arrival of this supposed millennium by issuing coins featuring that date and commissioning a historical work. Badauni also informs us that the date alf was used on coins even after the hijri calendar was officially abandoned. In other words, the coins minted after A.H. 990 still carried the date alf.

Without the benefit of Badauni’s information, all alf coins would be automatically assigned to the year A.H. 1000 (AD 1592) in museum listings and numismatic studies. (Haider 02)

Prof. Najaf Haider proposes that when the alf came around, a decision was made to return to the previous system, using the Ilahi instead of the Hijari year. This suggests that the mints in question operated continuously during the 1580s without indicating their specific names on the coins. This change seemed to only impact the gold and silver mints, leaving the copper mints unaffected. (Haider #)

Image: Gold coin (muhar) of Akbar dated alf and minted at Urdu Zafar Qarin.

Source: Najaf Haider, “The Monarch and the Millennium”.

Professor Haider contends that Emperor Akbar’s persistent issuance of alf coins over a decade and his belief in himself as the messiah were influenced by the Nuqtawiya philosophy. Originating in 15th century Iran and advocated by its founder Mahmud Pasikhani, the Nuqtawiya sect interpreted the progress of time and humanity in terms of cycles of eras and the leadership of a prominent prophet in each millennium. Nuqtawiya measured the duration of Islam from its inception rather than the year of Prophet Muhammad’s hijrat to Medina. Akbar embraced the Nuqtawi logic that A.H. 990 marked the beginning of an end, and that the apocalypse would unfold over the decade, culminating with the arrival of the year alf (1000) in the Islamic (hijri) calendar. Hence, each year following 990 essentially represented an alf year until the anticipated date. The continuous minting of alf coins year after year can be attributed to this line of thinking. (Haider 07)

In addition to this, many scholars argue that omitting the minting year and place from coins was done to address the issue of moneychangers (sarrafs) discounting (batta) more than the officially prescribed rates. By removing mint identification and standardising the coins to be identical in year and mint, the regulation of the exchange business sought to eliminate the opportunity for moneychangers to levy discounts on specific coins. (Haider 59) (Deyell 35).

There can be many reasons for this but one thing that is clear is that mint operations continued uninterrupted during the period in question. The observed changes solely pertain to the system of coin dating and the inclusion of the mint name. Furthermore, by circa 1590, Akbar demonstrably abandoned the ‘alf’ experiment, favouring a novel approach to coin dating that incorporated both regnal years and contemporaneous events. This shift coincided with the inauguration of the Ilāhi era, a solar-calendar-based system. Additionally, Akbar appears to have relinquished both millennialist beliefs and the confines of the Islamic framework, embracing a novel conception of sovereignty. Drawing inspiration from Ibn al-‘Arabī’s pantheistic ideas and the social contract theory governing the relationship between ruler and ruled, Akbar ultimately espoused the doctrine of absolute peace or Sulh-i Kul.

Works Cited

Badauni, Abdul Qadir. Muntakhab u’t-Tawarikh. Edited by William Lees and Ahmad Ali, vol. 2, Calcutta, Bib. Ind., 1864-69. 3 vols.

Deyell, John S. “The Development of Akbar’s Currency System and Monetary Integration of the Conquered Kingdoms.” The Imperial Monetary System of Mughal India, edited by John F. Richards, Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 13-67.

Deyell, John S. “Numismatic Methodology in the Estimation of Mughal Currency Output.” Indian Economic Social History Review, vol. 13, 1976, pp. 393-401. 10.1177/001946467601300305.

Gupta, P. L. “The Gold Mohars of Akbar.” Indian Numismatic Chronicle, vol. 4, no. 2, 1965-66, pp. 157-58.

Haider, Najaf. “Disappearance of Coin Minting in the 1580s? A Note on the Alf Coins.” Akbar and His India, edited by Irfan Habib, OUP India, 2000, pp. 55-65.

Haider, Najaf. “The Monarch and the Millennium: A New Interpretation of the Alf Coins of Akbar.” Coins in India: Power and Communication, edited by Himanshu Prabha Ray, Marg Publications, 2006.