Article written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Sawai Singh Panwar

Do you remember the trope your mother used to make you fall asleep as a kid- “soja beta, varna bhoot aa jayega?” But a Maharashtrian mother in Ratnagiri district may instead say, “soja beta varna hastar aa jayega!” Sounds similar yet unique, right? The only difference between both versions is the use of names peculiar to a region. This is the beauty of folk culture. It means aspects of culture like food habits, religious practices, stories, legends and so forth that are distinctive to a community or area. Folk culture can be diffused through orality or participation in an activity until it has been mastered. The depiction of folk elements in Indian cinema is developing these days. Side-by-side the audiences are getting familiar with “regional cinema” through over-the-top (OTT) platforms. Such attempts give an idea about practices and legends popular within India’s geography. This essay will focus on five films: Duvidha and Paheli, Bulbbul, Jallikattu and Kantara to open a conversation on popular folktales and practices, their intended messages and historical importance and whether such realities will get more chances in the future.

Beginning with the first two films, Duvidha (1973) starring Raisa Padamsee & Ravi Menon and Paheli (2005) starring Rani Mukherjee & Shahrukh Khan, are an adaptation of a Rajasthani folktale Duvidha written by Vijaydan Detha. The original story surrounds the life and dilemma of Lachchi who gets married to a merchant’s son (Kishanlal), who is a business-minded individual, while she is fifteen. As they travel from her home to her in-law’s place through palanquin, a ghost gets attracted to her. Post reaching, Kishan reveals to her that he will travel to another area for five years to do a profitable venture, leaving her alone. However, the ghost takes advantage of this opportunity, takes Kishan’s shape and comes back to haveli. What happens next is enough to astonish the reader. The ghost leaves Lachchi in a dilemma by sharing his true identity and gives her the choice to accept or reject him. Truly empowering dilemma, isn’t it? What follows next in the four years is the consensual romance, Lachchi’s pregnancy leading to the comeback of original Kishan, the ultimate revelation and the ghost being sealed in a bag and thrown into the well.

The important messages of the story in films are as follows:

Lachchi as an empowering figure: Her character is written in a way that every woman would relate to. She gets married at fifteen, and her husband leaves her for five years yet her opinion is never asked for. Kishan even refuses to take her with him. But two of her decisions stand out: first is when she accepts the choice of the ghost to be her husband because, for the first time, someone is bothered regarding what she wanted. Her second decision occurs only in the movie Paheli when she confronts the real Kishan in the climax and reveals that the relationship between her and the ghost was consensual. Therefore, it is difficult for her to start a new life with him. This shows Lachhi’s maturity and realism. On the contrary, the original story portrayed Lachchi to follow her in-laws’ choices silently accepting her destiny by forgetting the ghost.

Teaching moral lessons through Ghost: The Ghost comes to Lachchi due to his wish but reveals his identity (honesty) and ultimately gives her the choice (consent) to accept or reject this relationship. Moreover, he forms the image of an ideal husband who loves and takes care of his wife, and is not completely drowned in the greed of money, which is the epicentre of a merchant’s life. Lastly, he gives a counter message to society that it is a woman who completes a man and not vice versa.

The irony of society: While Lachchi is pregnant, both of them crave a baby girl knowing the fact that what a girl goes through. This message reflects the exact craving of Indian families to be blessed with a Lakshmi (girl) but she eventually becomes a burden because she is the family’s honour and her marriage centres around dowry. Paradoxically this surely is not the case if a kul ka deepak (boy) is born.

Rajasthani elements: Folk dance and music are components of both these films but Paheli uses additional tropes. For instance, the use of two puppets who appear on the screen and give a commentary takes forward the story’s intrigue value. Additionally, the inclusion of a Camel race.

The next film in the slot is Bulbbul starring Tripti Dimri, Rahul Bose, Avinash Tripathi, Paoli Dam and Parambrata Chatterjee. The themes shown in the movie are a combination of folklore, fairytale, superstitions and mythology. The story starts by portraying Bulbbul as an innocent girl who later turns into a men-hunting chudail when she is brutally beaten up by her husband, followed by getting raped by her brother-in-law wherein she dies during the heinous act.

Historically, chudails are those women who perished during their pregnancy or childbirth or at the hands of mistreatment by their husbands or their in-laws. They haunt or target anyone random or those who abused them. This seems a logical explanation but there is a twist in the tale. In the film, post Bulbbul’s death, she wakes up and is shown to be possessed by Goddess Kaali, the most revered form of Goddess Shakti, who kills demons around her and has an image of a warrior goddess. In this manner, Bulbbul is symbolised as a saviour Kali by the female victims and chudail by villagers (men).

Talking about witches can remind one of a popular phenomenon still prevalent in certain areas: Witch-hunting. It became popular in India, especially during the British period. The endless reasons for branding a woman as a witch include: the death of a child, a disease outbreak in a village, bad weather, a meagre harvest or plain insolence and so forth. This leads to their banishment from their communities, getting fined and, in extreme cases, being executed or even raped. If one looks into the reality of the recent trials, they are against the women who crossed the boundaries of the patriarchal society. In data released by NCRB (National Crime Records Bureau), more than 2,500 women have been hunted from 2000-2016. A recent case took place in November 2022 (Bihar). Therefore, the film becomes integral to highlighting the practices still prevalent around us.

Next is 2019’s Malayalam flick Jallikattu starring Antony Varghese, Chemban Vinod, Sabumon Abdusamad. Jallikattu is a local sports festival of Tamil Nadu, also called Salikkattu, which is a tradition of worshipping cattle stock as part of Pongal’s festival. It has ancient roots. The idea of the festival is simple: a bull is released in a crowd of people and whosoever gets hold of the bull and claims the bag of coins tied to it, is declared the winner. There are also high chances of injuries to both the bull and the man.

Keeping this idea at the core, the film follows the story of a buffalo escaping its slaughter for meat and creating havoc in the whole village. As a result, people are locked within their homes even affecting the craving of consuming beef. This is followed by a cat-and-mouse game between villagers and the bull wherein the prize for the winner will not be the coins, but the flesh of the beef itself. In the end, the bull gets buried in the mud while people climb on him and on each other, building a heap, for its ownership (see images below). This leaves the viewer with a thought that whose life matters: the life of human greed or the animal? And to what extent have we transformed ourselves from the baba adam zamana (ancient period) to modern human beings?

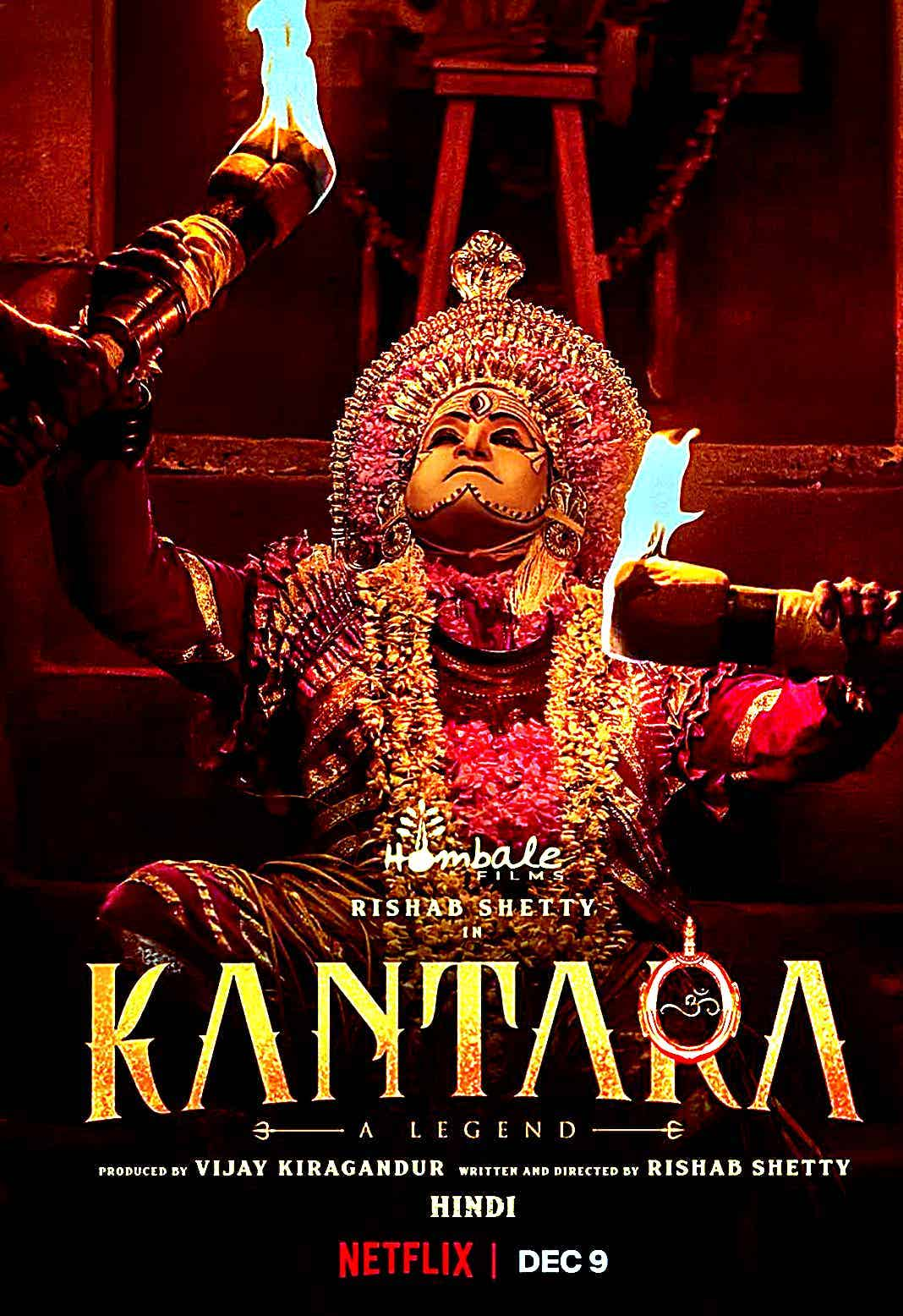

The last film Kantara (2022), starring Rishabh Shetty, has been witnessed by many people on big and small screens. It highlights the mixing of legend and folk practices: the celebration of Bhoota Kola wherein the worship of daiva Panjurli and Gurliga is done using folk practices. The daiva possesses the body of the performer and solves the problems of the villagers by suggesting solutions. This practice can be seen in other parts of the country, for instance, in Rajasthan where Bhopa, who is the priest of a public shrine, gets possessed by the deity and answers the everyday problems of the locals through a trance-like state.

Another refreshing aspect of the story is regarding the local forms of God. The daiva Panjurli and Gurliga are worshipped together due to their mythological stories. The Panjurli daiva has one root that attaches him to God Vishnu in the form of Varaha (boar). This is one example of bringing the local cults into the broader folds of Hinduism. This type of politics has been seen in history when tribal regions were brought under the fold of Hinduism through agriculture or Hindu kings and their folk elements were Hindu-ized. The best example of this is the cult of Jagannatha which historian Eschmann argued had tribal origins but got gradually Sanskritized, losing its original identity. Hence, it is crucial to gain knowledge of one’s ancestral or community’s deity to stay rooted.

In the end, most of the films on such themes are tagged as art cinema which the masses stay away from. Hence it is crucial for directors to make their stories compelling for commercial cinema to increase the life and afterlife of more characters like a woman (Lachchi), a chudail (Bulbbul), a bull and local gods (Panjurli and Gurliga). In this way cinema helps to dive deep into regions and their psyche regarding certain things. It indeed will be fascinating to see which next lore Indian cinema picks up as Kantara’s success has spoken of the masses craving for more. To end this essay, two lines from Paheli’s song Phir Raat Kati convey to the audience the evergreen importance of folktales- “Arey samay guzar jayega babu, Lok Katha reh jaayegi.”

Bibliography

Bharucha, Rustam. Rajasthan, an Oral History: Conversations with Komal Kothari. Penguin Global, 2003, pp. 122-123.

Detha, Vijaydan. The Dilemma and other stories. Translated by Ruth Vanita. Manushi Prakashan, 1997.

Raveendran, Prasadita L. “Myth and Folklore Embodiment in the Female Protagonists of Contemporary Fictions: A Reading of the Shiva Trilogy and Bulbbul” in Poetika Jurnal Ilmu Sastra, Vol. 9, No. 1, June 2021, pp 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.22146/poetika.v9i1.60734

Articles

Jain, Swarnim. The ‘Chudail’ Archetype Is the Personification of Society’s Fear of Assertive Women, Live Wire, July 2nd 2020.

https://livewire.thewire.in/out-and-about/movies/bulbbul-chudail-archetype-assertive-women/

Masoodi, Ashwaq. Witch hunting: Victims of superstition, Mint, 23rd February 2014.

https://www.livemint.com/Politics/Nnluhl4wjhiAAUklQwDtOL/Witch-hunting–Victims-of-superstition.html