Age of consent in our times refers to the age at which a person is considered a responsible legal actor in agreeing to participate or engage in a sexual act with their partner. The current age for the same stands at 18 years for both men and women under the Prevention of Children against Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act of 2012. This seemingly natural act has witnessed an arduous journey throughout its history. Firstly, the age of consent was never defined for men to begin with before the POCSO Act. Moreover, when it was first instituted the age of consent for ‘women’, stood at the age of 10, an age where a gendered term like a man or woman should not even be considered appropriate to address a child legally. Therefore, this article will aim to trace the evolution of consent laws in India from the boulevards of colonial legislature to the avenues of democratic India, highlighting simultaneously, the growing sensibility of the postcolonial legislature.

The age of consent with the Indian Penal Code of 1860 stood at 10. Traditionally, in Hindu conjugality, the first stage in the marital alliance was the garbhadan ceremony, i.e., the mandatory cohabitation between a man and a woman as soon as she hit puberty. The initial act was drafted with the indigenous customs of the colonial subjects in mind. Nonetheless, the reformers were equally aware of the ramifications of child marriages. These apprehensions turned into public discourse with the publication of Behramji Malabari’s notes on ‘Infant Marriage’ and ‘Enforced Widowhood ’ in 1884. A reformer and a journalist, he highlighted the perils of child marriages by associating it with early widowhood, young motherhood leading to the birth of sickly children, and giving up studies by boy husbands due to familial responsibilities among other reasons. He further argued for the increase in the age of consent from 10 to 12. As a result, these works drew extreme reactions from both sides. The liberal reformers appreciated the observations made by Malabari and even a few societies came up in his support, such as one by a jurist from Ahemadabad, Dayaram Gidumal. On the other hand, his work drew flack from the orthodoxy and Hindu revivalists who saw it as an uneducated opinion on Hindu customs.

(B. M. Malabari; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

This public discourse gained momentum with two of the most notable cases in Indian legal history, the Rukhmabai Dadaji case and that of Phulmonee Devi. Rukhmabai was a woman who was married at 11 to a 19-year-old, Dadaji Bhikaji. Upon reaching adulthood, Rukhmabai started living separately from her husband. Consequently, Dadabhai filed a case in the Bombay High Court demanding the restitution of conjugal rights in 1884. Rukhmabai, on the other hand, cited that she was not liable to continue in a marriage that had occurred in infancy. The case first went to Justice Robert Hill Pinhe, who had dismissed Dadaji’s appeal. Upon a new hearing under Justice Farhan, Rukhmabai was eventually given two choices, either to join her husband in conjugality or to face six months imprisonment. Subsequently, Rukhmabai chose the latter, which sent shockwaves across the country, dividing the reformist and orthodoxy into two factions. The case ended with an out-of-court settlement in 1888, where Dadaji relinquished his marital claims over Rukhmabai. Additionally, during the trial, Rukhmabai had gathered public support through her writings in the Times of India under the pseudonym, ‘A Hindu Lady’, which also drew attention to the broader issues of women’s rights and gender equality.

( Rukhmabai was also one of the first practicing female doctors in colonial India; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The sexual abuse of the infant brides was an issue that had gained no acknowledgement either from the reformers or the orthodoxy. This did not mean that such incidents were alien to the common public, but rather the civil society chose to overlook them. It was in 1890 that the Phulmonee Dasi case took place which proved to be a turning point in the evolution of consent laws in India. Phulmonee Dasi was an 11-year-old child married off to a 35-year-old Hari Maiti. However, she died on her wedding night after being raped to death by her husband. He was not charged with rape or homicide though, as the existing legal provisions did not consider the sexual intercourse with a wife above the age of 11 as rape.

The Phulmonee Dasi case shed light on the plight of child brides across the nation. The reformist press began publishing reports of similar incidents of abuse or violence. Similary, 44 women doctors presented a list of numerous cases where child brides had either been maimed or killed. Another Indian doctor highlighted that 13 per cent of the maternity cases he had dealt with had involved mothers below the age of 13.

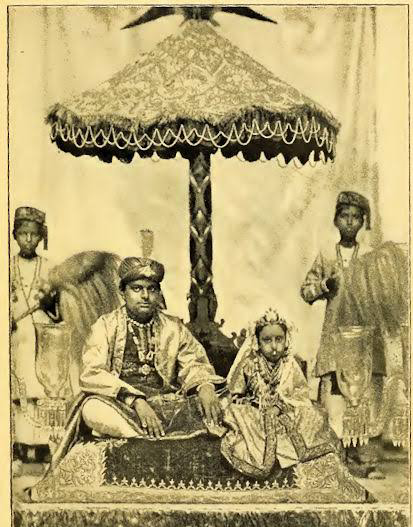

(A child bride in colonial India; Source: Old Indian Photos via www.payer.de)

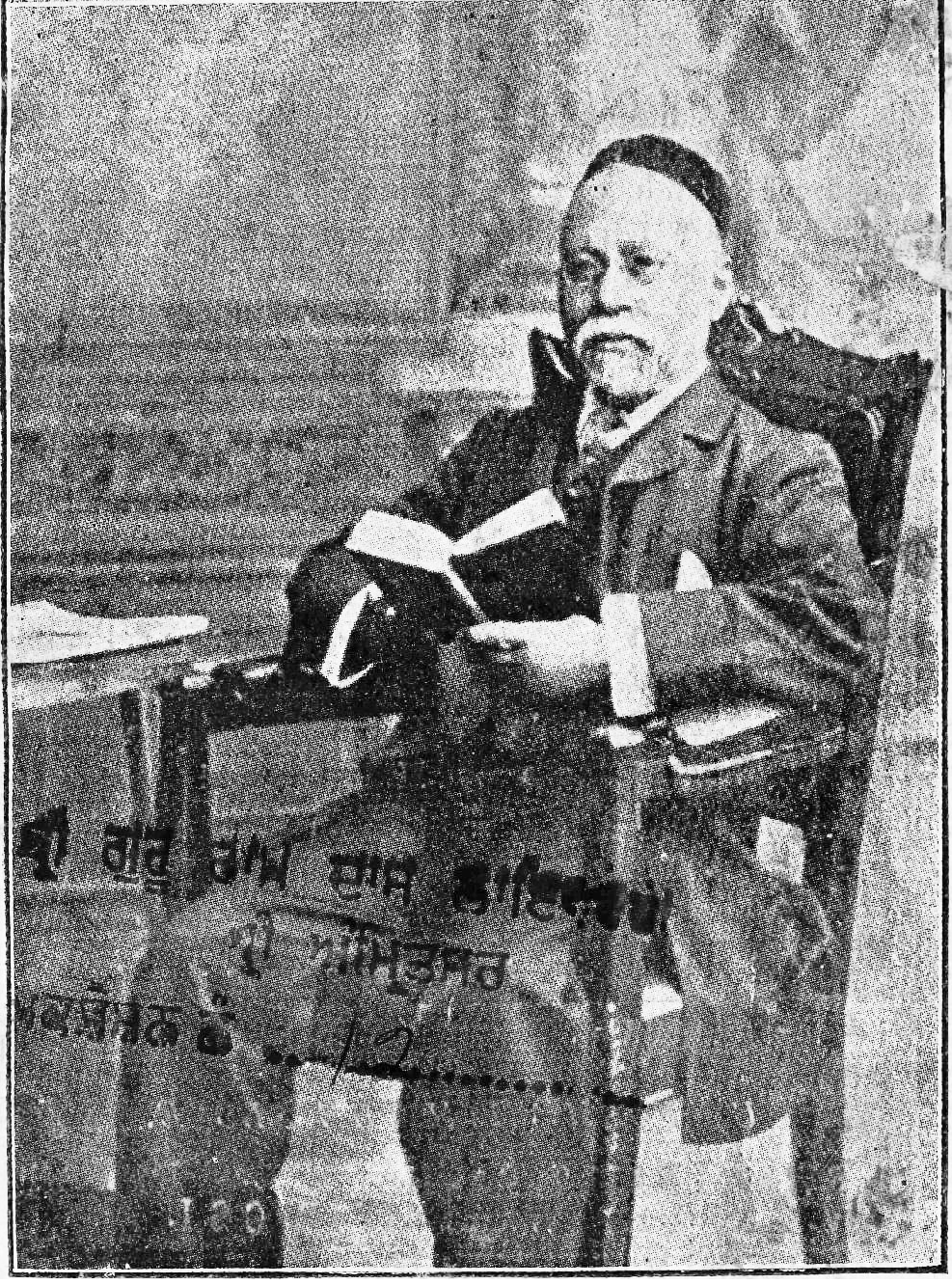

As a result of this discourse, on 19 March 1891, the Age of Consent Act came into being under the government of Lord Lansdowne who was equally disgusted by the brutality of the Phulmonee Dasi case. This case increased the age of consent for sexual intercourse for women, both married and unmarried from 10 years to 12. This meant that any sexual act committed on a girl below the age of 10 was, by law, to be considered rape. This act received widespread opposition from the Hindu orthodoxy which considered it an outright infringement on their personal space. They perceived it as an attack on the sanctity of the Hindu marital bond. The nationalists, on the other hand, viewed it as a law constituted by foreign legislators without the advice or consideration from the learned Hindu men.

It should not be construed that the notion of consent surrounding the discourse was associated with mental compatibility or the choice of women at any point. Neither the orthodoxy nor the reformists were concerned with the agency of women in this debate, their primary issue revolved around pain and coercion and whether a woman below the age of 12 was physically capable of bearing children.

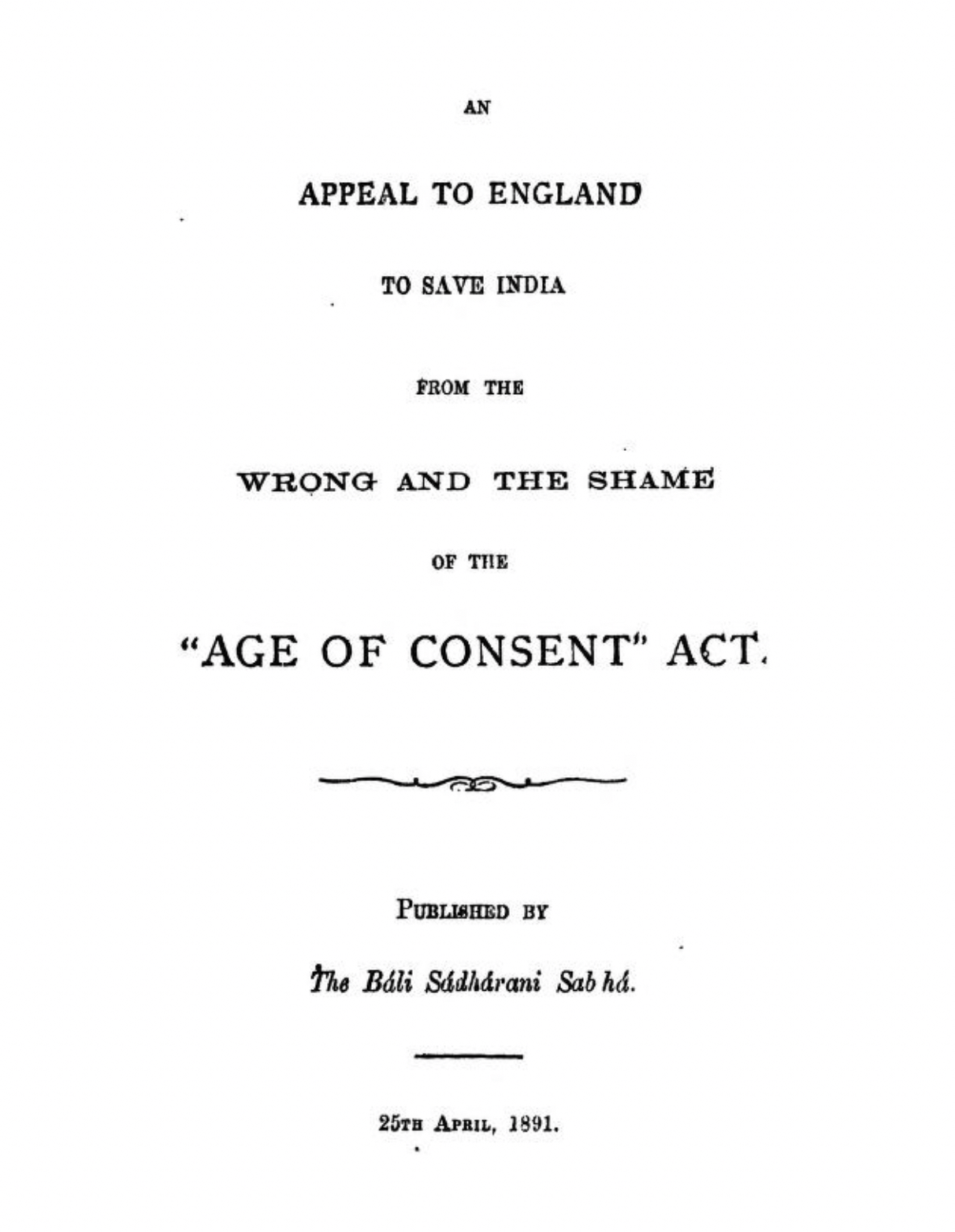

(A text published to oppose the Age of Consent act by the Bali Sadharani Sabha; Source: archives.org)

It was not until 1929 that the legal age of marriage would be increased. With the advent of women in the political arena, discussion around women’s health, child marriages and their education came to the foreground. As a result, the legal age of marriage was increased from 12 to 14 years for women under the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929. Later, in 1949 the age of consent under the rape law was increased to 15 years. This, in turn, became the basis of the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 where the minimum age for marriage was set at 15 years for women and 18 years for men. Though it was passed by the Parliament, this act remained aspirational in nature and did not render underage marriages void. The reason for this was that marriage was considered sacramental in the Hindu tradition and child marriages were a common phenomenon throughout the country. Moreover, any prosecutions that had taken place under this law were majorly due to family feuds and were not concerned with the emancipation of women.

The influence of rapid urbanisation and an increase in literacy among women, freeing the urban society from the clutches of religious orthodoxy, was more closely felt in the evolution of consent laws in India when, in the 1970s, the legal age of marriage for women was raised to 18 (21 for men) as per the recommendation of the Committee on the Status of Women.

It was finally in 2012 that the Protection of Children against Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act rendered any sexual act between partners below the age of 18 illegal, irrespective of the fact whether a minor consents to it. Though this act was an attempt to make significant strides in protecting minors and children from sexual abuse and exploitation, opponents to it have tried to argue that the increased age of consent also criminalises consensual acts between teenagers and disregards their sexual autonomy. Arguments have also been made to decrease the age of consent to 16, as there have been cases where partners consenting to sexual acts below the age of 18 have been accused of sexual assault by the family of the other. Though this argument is part of a more convoluted debate regarding consent and sexuality, the evolution of consent laws in India depicts the increased sensibility and the progress our society has made in the post-independence era.

Hence, we find how in Indian legal history, the age of consent debate that began solely with the concern over how child brides would not be healthy mothers and their bodies would not be able to bear the brunt of sexual penetration eventually in 2012 took the shape of POCSO Act where the legal age of consent of both the participants was considered necessary. The patriarchal nature of consent laws was finally done away with this act as the concern no longer revolved around a woman’s body being physically capable of indulging in sex but rather focused on an age where she would be able to exercise her agency and give consent as an adult. Legal debates aside, we still have a long way to go when it comes to understanding consent as a society and the agency of a woman, married or unmarried, in sexual relationships but the progress made by our civil society is still noteworthy, nonetheless.

References:

- Sarkar, Tanika. “Conjugality and Hindu Nationalism: Resisting Colonial Reason and the Death of a Child-Wife.” Women and Social Reform in Colonial India, vol. 1, edited by Sumit Sarkar and Tanika Sarkar, Permanent Black, 2007, pp. 385-419.

- Goyal, Hitishaa. “The Age of Consent in India (Historical and Contemporary Dimensions of Female Agency).” International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, vol. 7, no. 8, August, 2024, pp. 74-82.

- Varnekar, Sunil Sudhankar, and Upankar Chutia. “Navigating consensual relationship: Understanding the POCSO Act.” International Journal of Civil Law and Legal Research, vol. 4, no. 1, 2024, pp. 150-154.

- Agnes, Flavia. “Controversy over Age of Consent.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 48, no. 29, 2013, pp. 10–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23528498. Accessed 26 Aug. 2024.

- Joshi, Kokila. “B.M. MALABARI AND THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE AGE OF CONSENT BILL – 1891.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 59, 1998, pp. 614–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147030. Accessed 26 Aug. 2024.

- Chakrabarty, Roshni. “Rukhmabai Raut: From Child Bride to India’s first divorcee and female doctor.” India Today, March 9, 2024. https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/rukhmabai-raut-life-journey-indias-first-divorcee-first-female-doctor-feminist-2512498-2024-03-08

- Age of Consent Act Colonial Era India

- Age of Consent and Indian Legal History

- Age of Consent in Colonial India

- Age of Consent Legislation India

- Colonial India's Legal Reforms for Women

- Evolution of Consent Laws in India

- Historical Changes in India’s Age of Consent

- History of Age of Consent Laws in India

- Impact of Colonial Laws on Indian Women

- Legal Reforms for Women in India

- Women and Age of Consent Legislation

- Women’s Rights and Age of Consent in India