Brahmo journalism promulgated the basis for the creation of women’s magazines. ‘Vambodhini’ (1873), ‘Abala Mitra’ (1869), ‘Bang Mahila’(1870), ‘Balranjita’(1873), ‘Hindu Lalna’ (1875), ‘Paricharika’ ( 1878), ‘Khristi Mahila’ (1881) were some of the earliest examples of . in the Bengali language. Brahmo Samaj started ‘Tatvabodhini Patrika’(1843 – 1942) under the editorship of Akshay Kumar Datta, Keshav Chandra Sen started ‘Balbodhini Patrika’ (1863-1913) for women which Umesh Chandra Datta edited, Kamini Sil started the magazine ‘Christ Mahila’ in 1881 for Christian women in Bengali language, and Hemant kumari Choudharani started “Antpur”.

Early Indian women’s magazines were published in several languages and it played a significant role in championing the women’s question. It advocated for women’s education and condemned patriarchal social customs. Concurrently, they portrayed the ideal woman as a skilful wife and nurturing mother, educated but wholly domestic, the helpmate to the newly educated, middle-class man. Women’s education was vastly seen as an extension of Victorian grooming. A presentist viewpoint would see women’s magazines as a source of women’s continued subordination within the patriarchal family. Examining their historical context, however, reflects the mixed legacy of several women’s magazines, which were brave pioneers, fighting a lone battle when there were no frontiers.

This research examines the mixed legacy in the cases of several women’s magazines in Bengali. It takes several instances from different women’s magazines to present the act of balancing and establishing an equilibrium between tradition and modernity.

Origin

Pritha Lahiri uses the term “women’s magazine” to refer to those Brahmo and Hindu magazines whose content and advertisements were aimed primarily at female readers and at female areas of concern as customarily defined within the early twentieth Bengali culture. The Swadeshi movement kickstarted a new change in ideas, attitudes, and ideology of Bengali women. The women’s magazines responded to the “early flush of feminist consciousness.”

The thought of enlightenment which had been in the air since the mid-nineteenth century was materialized by the Bengali men in their ideological crusade when they found their strongest allies in their newly ’emancipated’ wives and daughters who, from the end of the nineteenth century, began to play a leading role through a spate of women’s magazines, in changing the older forms of women’s popular culture.

Women’s magazines gave a voice to the other sex. It gave a platform for women to share their worldview. It reconstructed women’s history from the perspective of a woman through different ways.

Women’s magazines were a renewable and inexpensive way to convey ideas to secluded women. It became a medium for secluded women to express their views beyond the confines of their homes.

These women’s magazines were edited, and also largely written by men, and thus they were less indicative of the concerns of women’s communication than of the subjects’ male social reformers deemed appropriate for a female audience”

Women’s magazines were dedicated to the “genteel woman” or bhodromohila. These magazines provided a discursive forum to probe the parameters, as well as the desirability (or otherwise), of a reinscribed female sensibility.

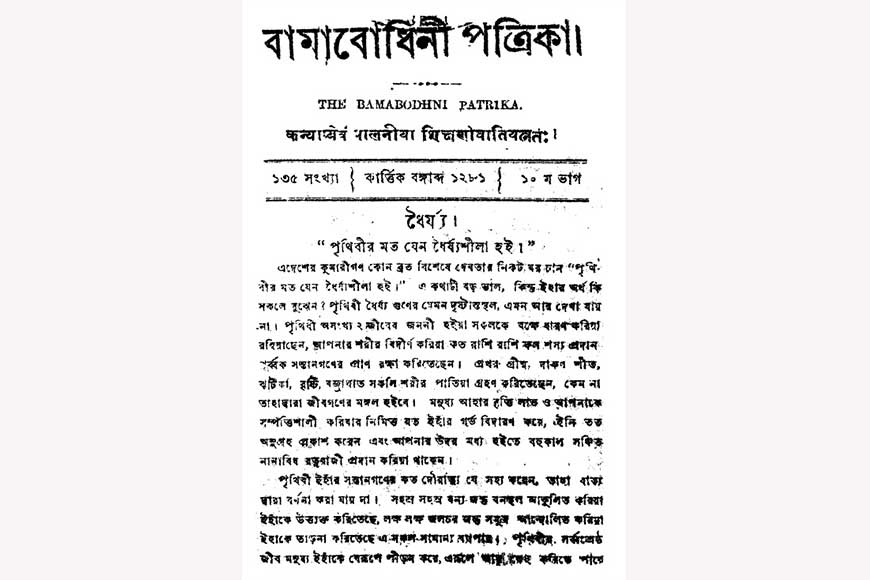

Journal for the Enlightenment of Women or Bamabodhini Patrika, was published from Calcutta in Bengali continuously between 1863 and 1922. The background leading to the creation of the magazine elaborates the reformist agenda for women in Bengal. The dilemma to accommodate the claims of antahpur (the inner space of the home, synonymous with the women’s area) with the call of the bahir (the space outside the home, or the mail domain), the conundrum of combining the Western-oriented modernization and the status quo maintenance of Indigenous tradition determined the contextual production of the magazine. Bamabodhini Patrika functioned as a crucial component of the novel solution working out to resolve this thorny problem.

Intent

Types of women’s magazines

Gail Minault classified women’s magazines as typified as either educational or literary, but at times they were a mixture of:

(a) practical information about health, child care, and nutrition, along with recipes and embroidery patterns;

(b) news about schools for girls, women’s associations, and women in other countries;

and (c) creative writing such as short stories, serialised novels, and poetry on themes deemed ’suitable’ for female readers.

There were other types of articles including arguments for or against certain social and educational reforms, discussion of customs that reformers regarded as useless and wasteful, women’s rights in Islamic law, or communications from readers offering opinions and asking for information or advice.

The nineteenth-century reformers from the Bhadrolok community developed and edited various woman-centred magazines aimed as instructional manuals. Deborah Anna Logan uses Masik Patrika (1854–1858) and Bambodhini Patrika (1863–1923) as examples. These periodical-styled magazines were used as suitable text/reading material for newly literate women. The topics comprised literature and language, history and geography, science and astronomy, hygiene and housekeeping, childcare and social problems, and religion.

Paradigm of Women’s Magazines

An issue of Bamabodhini Parika

Bambodhini Patrika was the first Bengali women’s magazine devoted to the cause of women” and the first to publish writing by women. It was an influential periodical of its time, praised for showcasing religious liberalism, raised social questions, and voiced for the modernization of women.

An 1868 article in Bamabodhim Patrika bemoaned the failure of the educated middle classes in taking the lead in female education. The article talked about how the Bethune School was functioning because of government assistance.

The increasing acceptance of modern education by women triggered a reaction, one being an accusation against women losing their skills in folk and native medicine. They were expected to know about four forms of treatment current in the later nineteenth century: allopathy, homoeopathy, kabiraji, and hakitni. An 1871 issue of Bamabodhim Patrika included a regular feature on elementary medical remedies. Antahpur used to have an occasional medical column.

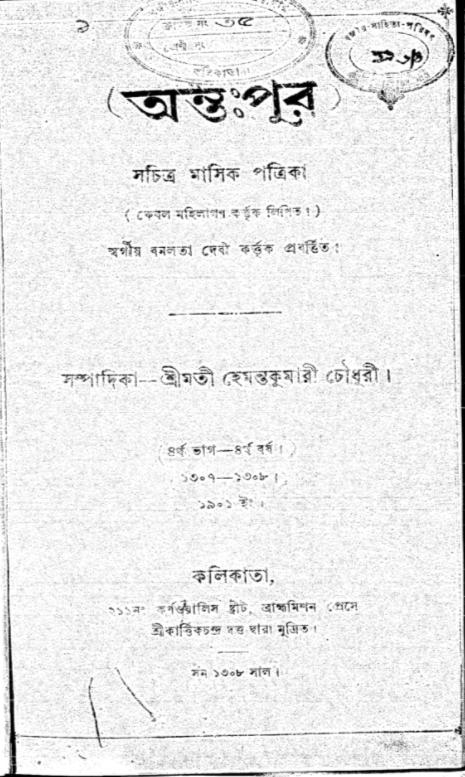

An issue of Antahpur magazine

Antahpur (1898) was edited and conducted by women solely. It was a “monthly illustrated Bengali journal for ladies, recommended for the Brahmo and other Hindus and lady missionaries.

Women’s magazines were also used as household manuals advising women to create a desirable peaceful atmosphere in the home. One woman advised her readers,

when your husband returns home from his official work or business, don’t burden him with anything, but wholeheartedly try to drive away the cares of his labor. At that time no bitter or unloving words should be said, and he should not be pestered for better ornaments or good clothes. Speak sweetly to him. See, as God has placed the burden of caring for the wife on the shoulders of her husband, the Supreme Father has likewise given women the responsibility of driving away their husbands’ cares.

During the wake of the boycott movement, women’s magazines carried advertisements for indigenous goods. A 1905 article on Antahpur carried an advertisement for a swadeshi soap made by the Bengal soap factory claiming that it is equal in quality to an English soap, and utilized political persuasion to market the commodity by propagating that a drain of lakhs of rupees abroad every year would be stopped if everyone vowed to purchase only swadeshi soap.

Women’s magazines played a crucial role in the process of defining a middle-class cultured woman. The end of the nineteenth century saw the “emancipated” women of the Bengali middle class who allied themselves with educated men replaced older forms of women’s popular culture with their “cultivated” writings,” especially in women’s magazines.

The emancipation of the newly educated middle-class women was complex. Even after acquiring and becoming proficient in new literary forms, she was dependent on the male head of the family. She had to strictly adhere to the traditional responsibilities of a respectable home, to receive literary apprenticeship. As a result, when they started writing, the bhadramahilas internalized the male concepts of the new womanhood. Kailashbashini Devi’s Hindu Mahilaganer Heenabastha, which was published in 1863 and favourably reviewed in contemporary newspapers, stressed the need for the education of women to free them from superstition, yet accepted this position: “From the particular nature and capacities with which God had endowed women, it is quite clear that the subservience of women is God’s will. By becoming strong, therefore, women can never become independent…. It does not become a woman to be without protection. An unprotected woman will not be respected anywhere. . . .” Hamangini Choudhury, writing in Antahpur, a women’s magazine, advises Bengali wives in these words: “Even if the husband uses abusive language out of blind anger and behaves rudely, the wife must accept it in silence. It is extremely improper to show disobedience before the husband. Even if you are at the point of death, you should never speak ill of your husband to others. . . .”

Women’s magazines drew a line between the sophisticated lady and the genteel woman. Kundamala Debi criticized the memsahib and advised the following in Bamabodhini Patrika in 1870:

If you have acquired real knowledge, then give no place in your heart to memsaheb-like behaviour. That is not becoming a Bengali housewife. See how an educated woman can do housework thoughtfully and systematically in a way unknown to an ignorant, uneducated woman. And see how if God had not appointed us to this place in the home, how unhappy a place the world would be.

Women’s magazines uphold the dichotomy of the women of East and West. Mahila edited by Girish Chandra Sen published an article entitled (Purba O Pashchimer Naribrinda ‘ (‘Women of East and West’), where the writer complained that “many ‘ nably mahila’ (modern women) of rich families usually neglect housework and cooking. They chat and crack jokes with each other as if God has created them for these amusements. It seems that they lack any high ambition and noble deeds in life.

Internal Resistance

The struggle during the boycott movement impacted women’s magazines. Several women’s writings emphasized the women’s world was beyond the four walls of the antapur.

Laiita Roy argued in an article entitled ‘Des Sebai Nari Jati ‘ (“Women at the service of the country”) that “The time has come when both man and woman have to stand side by side in the working place. My countrymen might say that women’s real working place is at home. If the woman does something outside her home or pays attention towards politics then she would neglect her duty as a wife and mother. But if a woman sits at home and the man outside then will the development of a home be possible? As long as the woman would remain subservient to man and the man would remain her master the country cannot be awakened.” Champakbala Debi made an appeal to God in Janhabi to arm women with patriotism along with self-reliance.

Consumerist Angle

Women were not only buying, writing for, reading, and consuming the subject matter of the women’s magazines but also the revenue-generating products they advertised.

Conclusion

Bengal led the way in publishing women’s magazines in the mid-to-late 19th century. Bengali women’s magazines like Antahpur and Bamabodhini Patrika are foundational sources for the study of social and religious reform in Bengal and for the lifestyles of the Bengali middle class.

Indian women’s magazines elucidated how polarized ideological formations, such as family/feminism, marriage/romance, and caste/class, are gathered into articulations of “good/bad” Indian tradition and “good/bad” modernity.

The magazines were part and parcel of the print culture which traces its roots to the establishment of colonial modernity. The social spaces of these women’s magazines were restricted to the literate women. Slowly and steadily, they became an important section of readers and consumers of print. They also gave a platform to the voices of women, creating a space for cultural discussion.

The subject matter of the women’s magazines ranged from purely medical discussions concerned with hygiene and disease, to discussions of household management, housework, and cooking, to delineations of family relationships and discussions of child rearing practice.

Nineteenth century Bengal preoccupied with social reform, and much of which focused on women. One of the key constituencies during this period was the women’s magazines, which offered an informal or non-institutional aspect of that moral education.women’s magazines like Bamabodhini Patrika, Mahila, Bangalakshmi, Bharat Mahila and Antahpur were instrumental in supporting the women’s cause.

The Swadeshi movement helped women permeate into the male-dominated world of politics and the women’s magazines reacted quickly to the changing scenario. The undertone of morality remained within all writings but the contributors of the women’s magazines, within their constraints, pushed to reform the existing traditional socio-familial framework.

The blended and confounded heritage of the women’s magazines shows a composite quality where tradition and modernity journeyed hand-in-hand. The riddling expedition of social reform surely presented a mixed legacy of the colonial era women’s magazines.

Bibliography

- Antahpura. (n.d.). Global Journal Portals. https://sismo.inha.fr/s/en/journal/263866

- Aquil, M. (n.d.). Negotiating Gender, Class and Nation: The Indian Ladies Magazine and the discourse of women’s emancipation in Colonial India. International Journal of Multidisciplinary, 4(6). https://old.rrjournals.com/past-issue/negotiating-gender-class-and-nation-the-indian-ladies-magazine-and-the-discourse-of-womens-emancipation-in-colonial-india/

- Bamabodhini Patrika of 19thcentury Bengal gave women of the Andarmahal a space to write. (2020, August 20). Get Bengal. https://www.getbengal.com/details/bamabodhini-patrika-of-19thcentury-bengal-gave-women-of-the-andarmahal-a-space-to-write

- Bannerji, H. (1992). Mothers and Teachers: Gender and class in Educational Proposals for and by Women in Colonial Bengal. Journal of Historical Sociology, 5(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.1992.tb00021.x

- Borthwick, M. (1984). The changing role of Women in Bengal, 1849-1905. In Princeton University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400843909

- Burning down the house. (2019). In Routledge eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429039775

- Colonialism, Nationalism, and Colonialized Women: The Contest in India on JSTOR. (n.d.). www.jstor.org. https://www.jstor.org/stable/645113

- Gooptu, S. (2021). Knowing Asia, being Asian. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003243786

- Lahiri, P. (n.d.). WOMENS’ MAGAZINES IN BENGAL, 1905-11 on JSTOR. www.jstor.org. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147036

- Lessons in Self-Fashioning: “Bamabodhini Patrika” and the Education of Women in Colonial Bengal on JSTOR. (n.d.). www.jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20084005

- Logan, D. A. (n.d.). The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, 1901–1938: From Raj to Swaraj. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Minault, G. (1988). Urdu women’s magazines in the early twentieth century. Manushi, 48. http://manushi-india.org/test/pdfs_issues/PDF%20files%2048/urdu_women’s_magazines_in_the_early_twentieth_century.pdf

- Minault, G. (1998). Women’s magazines in Urdu as sources for Muslim social history. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 5(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/097152159800500203

- Nisha Mude-Pawar. (2008). Women’s Magazine Tanishka: A Study. Karnatak University Journal of Humanities, 47. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nisha-Pawar-2/publication/348759263_Women’s_Magazine_Tanishka_A_Study/links/600fc566a6fdccdcb87efde8/Womens-Magazine-Tanishka-A-Study.pdf

- Sangari, K., & Vaid, S. (2006). Recasting women : essays in colonial history. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA78306647

- South Asia Open Archives – SAOA. (2021, January 24). Antahpura. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/105495927618411/photos/248513933316609/

- Walsh, J. E. (1997). What women learned when men gave them advice: Rewriting Patriarchy in Late-Nineteenth-Century Bengal. The Journal of Asian Studies, 56(3), 641. https://doi.org/10.2307/2659604